Jazz in Weimar and Nazi Germany, 1918–1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 6. the Voice of the Other America: African

Chapter 6 Th e Voice of the Other America African-American Music and Political Protest in the German Democratic Republic Michael Rauhut African-American music represents a synthesis of African and European tradi- tions, its origins reaching as far back as the early sixteenth century to the begin- ning of the systematic importation of “black” slaves to the European colonies of the American continent.1 Out of a plethora of forms and styles, three basic pil- lars of African-American music came to prominence during the wave of indus- trialization that took place at the start of the twentieth century: blues, jazz, and gospel. Th ese forms laid the foundation for nearly all important developments in popular music up to the present—whether R&B, soul and funk, house music, or hip-hop. Th anks to its continual innovation and evolution, African-American music has become a constitutive presence in the daily life of several generations. In East Germany, as throughout European countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain, manifold directions and derivatives of these forms took root. Th ey were carried through the airwaves and seeped into cultural niches until, fi nally, this music landed on the political agenda. Both fans and functionaries discovered an enormous social potential beneath the melodious surface, even if their aims were for the most part in opposition. For the government, the implicit rejection of the communist social model represented by African-American music was seen as a security issue and a threat to the stability of the system. Even though the state’s reactions became weaker over time, the offi cial interaction with African-American music retained a political connotation for the life of the regime. -

The Voice of Jazz Musicians in Germany

Felix Felix Falk Angelica Niescier Lucia Cadotsch Gunter Hampel Susan Weinert Shannon Barnett Robert Landfermann Olivia Trummer © Patrick Essex © Patrick Schestag © Rüdiger © Lothar Fietzek Achim Kaufmann Lillinger © Katrin Christian Lillinger Christoph Hillmann Julia Hülsmann Götz © Sven Volker Engelberth Schindelbeck © Frank Alexandra Lehmler Ulla Oster Peter Ehwald Germany MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION GERMAN JAZZ UNION - WHAT WE REPRESENT 0 Individual member 0 Sponsoring member The tasks and goals of the German Jazz Union e. V. are First name wide-ranging. The aim is to give “Jazz made in Germany” an German Jazz Union - appropriate social status within German and Europes diverse Last name cultural scene. Instrument Jazz in and from Germany is globally renowned and creates in- Institution (if applicable) novative potential in all areas of society. Public funding is just as essential for free scenes in jazz and improvised music as it is in Main occupation institutionalized music and culture. Street The German Jazz Union represents the interests of all jazz musicians in Germany and is particularly committed to the Postcode, City following goals: Tel. of Jazz Musicians in The voice 1. SPECIFIC FUNDING FOR JAZZ AND IMPROVISED Fax MUSIC Expansion of public funding, design of existing and new Mobile funding instruments at federal level. Jazz experts in relevant Email institutions. 2. VENUES Expansion of public funding for jazz and improvised music venues, creation of fully financed jazz Website centers. Stronger support from the federal states and local au- Date of birth thorities.3. FAIR COMPENSATION AND SOCIAL SECURITY Ensuring appropriate compensation. Short term minimum Annual membership fee (see back of leaflet) and long term fair fees for musicians, strengthening of social security, in particular through the expansion of the German IBAN Social Fund for Artists (Künstlersozialkasse). -

Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Michael James Schmidt 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Michael James Schmidt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany Committee: David F. Crew, Supervisor Judith Coffin Sabine Hake Tracie Matysik Karl H. Miller The Multi-Sensory Object: Jazz, the Modern Media, and the History of the Senses in Germany by Michael James Schmidt, B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 To my family: Mom, Dad, Paul, and Lindsey Acknowledgements I would like to thank, above all, my advisor David Crew for his intellectual guidance, his encouragement, and his personal support throughout the long, rewarding process that culminated in this dissertation. It has been an immense privilege to study under David and his thoughtful, open, and rigorous approach has fundamentally shaped the way I think about history. I would also like to Judith Coffin, who has been patiently mentored me since I was a hapless undergraduate. Judy’s ideas and suggestions have constantly opened up new ways of thinking for me and her elegance as a writer will be something to which I will always aspire. I would like to express my appreciation to Karl Hagstrom Miller, who has poignantly altered the way I listen to and encounter music since the first time he shared the recordings of Ellington’s Blanton-Webster band with me when I was 20 years old. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics Rusch, L. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Rusch, L. (2016). "Our subcultural shit-music": Dutch jazz, representation, and cultural politics. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 "Our Subcultural Shit-Music": Dutch Jazz, Representation, and Cultural Politics ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het College voor Promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op dinsdag 17 mei 2016, te 14.00 uur door Loes Rusch geboren te Gorinchem Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. -

Matthias Schriefl

MATTHIAS SCHRIEFL SHREEFPUNK PLUS STRINGS ACT 9657-2 German Release Date: February 23, 2007 Jazz, punk, and strings thrown in for the bargain - who on earth would dream up something like this? Matthias Schriefl: A young musician from the Allgäu, who has brought us all kinds of weird and wonderful ideas. The nice thing is: His ideas are infectious; each of his concerts is an inspiring event. Schriefl is a mere 25 years old, and yet the list of his awards and credits is amazing. He has shared the stage with the most successful international jazz musicians, and along with numerous young-talent awards, he is now receiving similar recognition in the grown-up leagues. One example is the renowned WDR jazz prize for improvisation. “is no surprise to ” says Reiner ü in the magazine WDR-Print, “ although he is still in his mid twenties, he has an instrumental control comparable to the old masters: He has a phenomenal range and chops, his talent as an improviser is thrilling, and his arrangements are no less original than his ”. Yet, ’energy and playfulness betray his age û in a most refreshing way. “’not afraid of simplicity, just as I ’fear ” Schriefl summarises the motto of his new recording, the ACT- debut Shreefpunk plus Strings (ACT 9657-2). The CD offers daredevil experimental jazz that in no way sounds clean or intellectual. The music conveys passion and humour and allows surprisingly outrageous outbursts. “is crazy enough to use ideas that others musicians would never dare ”, says professor Andy Haderer, lead trumpet player with the WDR, about his former student. -

Iasa Journal (Formerly Phonographic Bulletin)

lasa• International Association of Sound Archives Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores Internationale Vereinigung der Schallarchive iasa journal (formerly Phonographic Bulletin) no. 3/May 1994 IASA JOURNAL Journal of the International Associa~on of Sound Archives IASA Organe de I'AsSociation Internationale d'Archives Sonores IASA Zeitschrift der Internationalen Vereinig'ung der Schallarchive IASA Editor:' Helen PHarrison, Open University Library ,Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA. England. Fax: +44908 653744 . Reviews and RecenlPublications Editor: Pekka Gronow, Finnish Broadcasting Company, PO Box 10, SF ,00241, Helsinki, Finland. Fax: 358014802089 The IASA Journal is published twice a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership inlASAshould be sent to the SecreU:irY General (see list of officers below), The annual dues are DM40 for individual members and DM110 for institutional members. Back copies of the IASA Journal from 1971 are available on application. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the IASA Journal are also available to non-members at a cost of DM55. Le Journal de I'Association international d'archives sonores, le IASA Journal, est publie deux fois I'anet distribuea tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au secretaire dont vous trouverez l'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuelles sont en ce moment de DM40 pO!ll" les membres individuels et DMllOpour lesmembres institutionelles. Les numeros preceeentes (a partirde 1971) du IASA JOURNAL sont disponsib1es sur demande. Ceux qui ne sont pas menibres de I'Association peuvent obtenir un abonnement du IASA JOURNAL pour l'annre courante aucout de DM55. Da$IASA JOURNAL erscheint zweimal jahr!ich und geht alien Mitgliedern der IASA zu. -

Krautrock and the West German Counterculture

“Macht das Ohr auf” Krautrock and the West German Counterculture Ryan Iseppi A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF GERMANIC LANGUAGES & LITERATURES UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 17, 2012 Advised by Professor Vanessa Agnew 2 Contents I. Introduction 5 Electric Junk: Krautrock’s Identity Crisis II. Chapter 1 23 Future Days: Krautrock Roots and Synthesis III. Chapter 2 33 The Collaborative Ethos and the Spirit of ‘68 IV: Chapter 3 47 Macht kaputt, was euch kaputt macht: Krautrock in Opposition V: Chapter 4 61 Ethnological Forgeries and Agit-Rock VI: Chapter 5 73 The Man-Machines: Krautrock and Electronic Music VII: Conclusion 85 Ultima Thule: Krautrock and the Modern World VIII: Bibliography 95 IX: Discography 103 3 4 I. Introduction Electric Junk: Krautrock’s Identity Crisis If there is any musical subculture to which this modern age of online music consumption has been particularly kind, it is certainly the obscure, groundbreaking, and oft misunderstood German pop music phenomenon known as “krautrock”. That krautrock’s appeal to new generations of musicians and fans both in Germany and abroad continues to grow with each passing year is a testament to the implicitly iconoclastic nature of the style; krautrock still sounds odd, eccentric, and even confrontational approximately twenty-five years after the movement is generally considered to have ended.1 In fact, it is difficult nowadays to even page through a recent issue of major periodicals like Rolling Stone or Spin without chancing upon some kind of passing reference to the genre. -

Transtel Agriculture 122530 Documentary 30 X 10 Min

Your Partner for Quality Television DW Transtel is your source for captivating documentaries and a range of exciting programming from the heart of Europe. Whether you are interested in science, nature and the environment, history, the arts, culture and music, or current affairs, DW Transtel has hundreds of programs on offer in English, Spanish and Arabic. Versions in other languages including French, German, Portuguese and Russian are available for selected programs. DW Transtel is part of Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster, which has been producing quality television programming for decades. Tune in to the best programming from Europe – tune in to DW Transtel. SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY MEDICINE NATURE ENVIRONMENT ECONOMICS AGRICULTURE WORLD ISSUES HISTORY ARTS CULTURE PEOPLE PLACES CHILDREN YOUTH SPORTS MOTORING M U S I C FICTION ENTERTAINMENT For screening and comparehensive catalog information, please register online at b2b.dw.com DW Transtel | Sales and Distribution | 53110 Bonn, Germany | [email protected] Key VIDEO FORMAT RIGHTS 4K Ultra High Definition WW Available worldwide HD High Definition VoD Video on demand SD Standard Definition M Mobile IFE Inflight LR Limited rights, please contact your regional distribution partner. For screening and comparehensive catalog information, please register online at b2b.dw.com DW Transtel | Sales and Distribution | 53110 Bonn, Germany | [email protected] Table of Contents SCIENCE ORDER NUMBER FORMAT RUNNING TIME Science Workshop 262634 Documentary 7 x 30 min. The Miraculous Cosmos of the Brain 264102 Documentary 13 x 30 min. Future Now – Innovations Shaping Tomorrow 244780 Clips 20 x 5-8 min. Great Moments in Science and Technology 244110 Documentary 98 x 15 min. -

Musikindustrie in Zahlen: Jahrbuch 2015

MUSIKINDUSTRIE IN ZAHLEN 2015 UMSATZ Plus 4,6 Prozent: Deutscher Musikmarkt wächst 2015 deutlich STREAMING Plus 106 Prozent: Streaming Subscriptions übertreffen Prognose REPERTOIRE Acht der Top 10-Alben in den Offiziellen Deutschen Charts 2015 deutschprachig EDITORIAL INHALT 2 Editorial 4 Umfrage zur Musiknutzung 6 Ein Blick zurück 8 Umsatz 16 Absatz 20 Musikfirmen 24 Musiknutzung 28 Musikkäufer 34 Musikhandel 38 Repertoire und Charts 52 Jahresrückblick 53 Vorstände und Geschäftsführer 54 Impressum 1 EDITORIAL EDITORIAL Rotation waren und sind seit jeher un- ser Business! Gleichzeitig sind wir aber mit der relativen Langsamkeit des Rechts- rahmens konfrontiert, sei es im natio- nalen Bereich, sei es auf europäischer wenn man noch ein kleines bisschen Ebene, sei es mit Blick auf die zuneh- weiter zurückschaut, verzeichnen wir mend auch global zu besprechenden ZUKUNFT IM HIER UND JETZT sogar schon das dritte Jahr ein positives Rechtsthemen von Urheberrecht bis zu ODER: „DAUERND MORGEN“ Ergebnis. Woran liegt das? Wir haben Datenschutz. Allein der im November – UND EIN GUTES JAHR 2015 nach wie vor eine gesunde Balance aus 2015 wieder neu, diesmal vor dem Bun- So einiges, was wir im vergangenen Jahr physischen und digitalen Nutzungsfor- desverfassungsgericht aufgeschnürte Fall an dieser Stelle noch ziemlich weit ent- men und Musikformaten in Deutsch- „Metall auf Metall“ begleitet uns seit fernt am Horizont gesehen haben, ist land: Das Streaming wächst weiter 1997, seit bald 20 Jahren also. Die Lang- innerhalb der letzten zwölf Monate Teil kräftig, die CD-Umsätze sind moderat samkeit in Bezug auf manche Change- unserer Wirklichkeit geworden. Auto- rückläufig und Vinyl legte auch 2015 in Prozesse ist aber nicht nur den Müh(l)en nome Autos sind keine Konzeptskizze seiner Nische deutlich zweistellig zu. -

Ausgabe 11/12 – 2013

Veranstaltungskalender Bodensee - Oberschwaben Ammersee - Allgäu 11+12/2013 Joachim Kühn, Majid Bekkas und Ramon Lopez Jazz meets Gnawa-Tradition 15.11.2013 Spielboden Dornbirn © ACT/Lutz Voigtlaender Programm Herbs t/ Winter 2013 So. 24. November, 11 Uhr ANDORS JAZZ BAND Vintage jazz comes to town „Lindenhalle“, Kleiner Saal, Ehingen Do. 26. Dezember, 17 Uhr 2. Weihnachtsfeiertag BARBARA BÜRKLE & SWINGIN’ WOODS A Tribute to Nat King Cole „Lindenhalle“, Kleiner Saal, Ehingen Sa. 25. Januar 2014, 20.30 Uhr ACHIM SEIFERT PROJECT Zwischen Tradition und Moderne Brasserie „Amadeus “, Ehingen Fr. 21. Februar 2014, 20 Uhr Auskunft Jazzclub Ehingen e.V. CHRISTINA BRAGA mit ihrem TRIO Tel. 0 73 91 - 70 8 253 Samba, Jazz und Love www.jazzclub-ehingen.de „Franziskanerkloster“, Ehingen ja zz Jazzclub Lustenau club Jazzhuus Lustenau Rheinstraße 21 · A-6890 Lustenau Keep swingin’! www.jazzclub.at Freitag (Allerheiligen), 1. November 2013, 21:00 h, Jazzhuus Janysett McPherson Trio Janysett McPherson (vocals, piano, rhodes), Rafael Paseiro (bass), Dominique Viccaro (drums) Freitag, 15. November 2013, 21:00 h, Jazzhuus SwingWerk im Rahmen der Lustenauer „Langen Nacht der Musik“ Unter der Leitung von Werner Gorbach spielen 19 (!) Musiker swingende Bigbandarrangements. Freitag, 6. Dezember 2013, 21:00 h, Jazzhuus Larry Goldings / Peter Bernstein / Bill Stewart im Rahmen der „Jazztage Lustenau“ Larry Goldings (organ), Peter Bernstein (guit), Bill Stewart (drums) Freitag, 20. Dezember 2013, 21:00h, Jazzhuus Weihnachtsjazz mit dem „Thierry Lang Trio und Matthieu Michel“ Matthieu Michel (flh), Thierry Lang (piano), Heiri Känzig (bass), Kevin Chesham (drums) Inhalt 3 Impressum 4 Jazz November 2013 11 Abo-Karte 30 Jazz Dezember 2013 Impressum Herausgebe r/ Layout DTP Service Sigrid Wasmer Birkenallee 14, 86949 Windach Tel. -

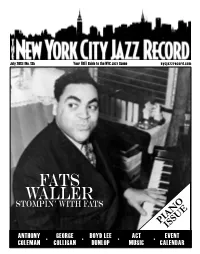

Stompin' with Fats

July 2013 | No. 135 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com FATS WALLER Stompin’ with fats O N E IA U P S IS ANTHONY • GEORGE • BOYD LEE • ACT • EVENT COLEMAN COLLIGAN DUNLOP MUSIC CALENDAR “BEST JAZZ CLUBS OF THE YEAR 2012” SMOKE JAZZ & SUPPER CLUB • HARLEM, NEW YORK FEATURED ARTISTS / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 ONE NIGHT ONLY / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 RESIDENCIES / 7pm, 9pm & 10:30 Mondays July 1, 15, 29 Friday & Saturday July 5 & 6 Wednesday July 3 Jason marshall Big Band Papa John DeFrancesco Buster Williams sextet Mondays July 8, 22 Jean Baylor (vox) • Mark Gross (sax) • Paul Bollenback (g) • George Colligan (p) • Lenny White (dr) Wednesday July 10 Captain Black Big Band Brian Charette sextet Tuesdays July 2, 9, 23, 30 Friday & Saturday July 12 & 13 mike leDonne Groover Quartet Wednesday July 17 Eric Alexander (sax) • Peter Bernstein (g) • Joe Farnsworth (dr) eriC alexaNder QuiNtet Pucho & his latin soul Brothers Jim Rotondi (tp) • Harold Mabern (p) • John Webber (b) Thursdays July 4, 11, 18, 25 Joe Farnsworth (dr) Wednesday July 24 Gregory Generet George Burton Quartet Sundays July 7, 28 Friday & Saturday July 19 & 20 saron Crenshaw Band BruCe Barth Quartet Wednesday July 31 Steve Nelson (vibes) teri roiger Quintet LATE NIGHT RESIDENCIES Mon the smoke Jam session Friday & Saturday July 26 & 27 Sunday July 14 JavoN JaCksoN Quartet milton suggs sextet Tue milton suggs Quartet Wed Brianna thomas Quartet Orrin Evans (p) • Santi DeBriano (b) • Jonathan Barber (dr) Sunday July 21 Cynthia holiday Thr Nickel and Dime oPs Friday & Saturday August 2 & 3 Fri Patience higgins Quartet mark Gross QuiNtet Sundays Sat Johnny o’Neal & Friends Jazz Brunch Sun roxy Coss Quartet With vocalist annette st. -

Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin, Vol. 2, Spring 2018 Maria Ebner Fordham University

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Modern Languages and Literatures Student Modern Languages and Literatures Department Publications Spring 2018 Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin, Vol. 2, Spring 2018 Maria Ebner Fordham University Paula Begonja Fordham University Evan Biancardi Fordham University Elodie Huston Fordham University McKenna Lahr Fordham University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/modlang_studentpubs Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, Modern Languages Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ebner, Maria, ed. Kiez Kieken: Observations of Berlin. Vol. 2, Spring 2018. Bronx, NY: Modern Languages and Literatures Department, Fordham University. Web. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages and Literatures Department at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages and Literatures Student Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Maria Ebner, Paula Begonja, Evan Biancardi, Elodie Huston, McKenna Lahr, Sophie Lee, Mackenzie Norton, Ann Pekata, Catherine Rabus, and Timothy Uy This article is available at DigitalResearch@Fordham: https://fordham.bepress.com/modlang_studentpubs/4 ii k i k zz i nn KKK Observations of Berlin Stories of the Stasi Files, SOPHIE LEE Turkey in Berlin. The Emergence of Oriental Rap Countercultural Art in Berlin,