Downloading the Available Texts from the Gutenberg Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Nugget

WODEHOUSE THE LITTLE NUGGET NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 11794 7081 I 1 Lr W Wodehouse, P. G. The 1 ittle nugget / 874858 TheNe Public Aator, Lenox and 1 Penguin Books The Little Nugget P. G. Wodehouse was born in Guildford in 1881 and educated at Dulwich College. After working for the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank for two years, he left to earn his living as a journalist and storywriter, writing the 'By the Way* column in the old Globe. He also contributed a series of school stories to a magazine for boys, the Captain, in one of which Psmith made his first appearance. Going to America before the First World War, he sold a serial to the Saturday Evening Post and for the next twenty-five years almost all his books appeared first in this magazine. He was part author and writer of the lyrics of eighteen musical comedies including Kissing Time; he married in 1914 and in 1955 took American citizenship. He wrote over ninety books and his work has won world-wide acclaim, being translated into many languages. The Times hailed him as 'a comic genius recognized in his lifetime as a classic and an old master of farce'. P. G. Wodehouse said, *I believe there are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making a sort of musical comedy without music and ignoring real life altogether; the other is going right deep down into life and not caring a damn . .' He was created a Knight of the British Empire in the New Year's Honours List in 1975. -

Eedp5 (Download) Uneasy Money Online

eEDp5 (Download) Uneasy Money Online [eEDp5.ebook] Uneasy Money Pdf Free P.G. Wodehouse DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2015-11-28 9.00 x .42 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1519577893186 pages | File size: 78.Mb P.G. Wodehouse : Uneasy Money before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Uneasy Money: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Good classic Wodehouse.By Christophe R. WorthThe book was typical Wodehouse, always fun, light, and well plotted and written. I always like characters that are a little dark. In Uneasy Money, Claire and Didley Pickering are two. Wodehouse has a way of including darkness in his great comedy which I find very interesting and funny.The format of this particular printing drove me nuts. Why the large format (7" by 10")? And the automatic formatting made more than a few formatting errors, making the text harder to read. Part of the pleasure of reading a book (as opposed to reading a computer) is holding the real paper and ink in my hands. The unnecessary large format and weird layout of the text on the pages eliminated most of the "reading a real book" satisfaction. I will stay away from this publisher, Wilder Publications, in the future.I also like to think that books like this one reflect Wodehouse's experiences in the entertainment world of New York in the early 20th century. Characters like the Good Sport and Lady Pauline Wetherby and performances like the Dream of Psyche are classic Wodehouse. -

Uneasy Money Online

KAIrL [Free read ebook] Uneasy Money Online [KAIrL.ebook] Uneasy Money Pdf Free P. G. Wodehouse ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook 2012-06-14Format: Large PrintOriginal language:English 10.00 x .65 x 7.75l, #File Name: 1442932589288 pages | File size: 38.Mb P. G. Wodehouse : Uneasy Money before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Uneasy Money: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Good classic Wodehouse.By Christophe R. WorthThe book was typical Wodehouse, always fun, light, and well plotted and written. I always like characters that are a little dark. In Uneasy Money, Claire and Didley Pickering are two. Wodehouse has a way of including darkness in his great comedy which I find very interesting and funny.The format of this particular printing drove me nuts. Why the large format (7" by 10")? And the automatic formatting made more than a few formatting errors, making the text harder to read. Part of the pleasure of reading a book (as opposed to reading a computer) is holding the real paper and ink in my hands. The unnecessary large format and weird layout of the text on the pages eliminated most of the "reading a real book" satisfaction. I will stay away from this publisher, Wilder Publications, in the future.I also like to think that books like this one reflect Wodehouse's experiences in the entertainment world of New York in the early 20th century. Characters like the Good Sport and Lady Pauline Wetherby and performances like the Dream of Psyche are classic Wodehouse. -

Love Across the Atlantic: an Interdisciplinary Conference on US

Love Across the Atlantic: An Interdisciplinary Conference on US-UK Romance University of Roehampton, June 16 2017 In conjunction with New College, University of Alabama 9.30am – 10.00am – Registration – Reception, ground floor Elm Grove building Tea & coffee (and refreshments throughout the day) on the 4th floor of Elm Grove from 9.30am NB Keynotes, all panels and closing remarks will be on the 3rd floor of Elm Grove 10.00 – 11.20 – Welcome & Keynote 11.20 – 11.45 – Break 11.45 – 1.25 – Panels 1a and 1b 1.25 – 2.15 – LUNCH 2.15 – 3.35 – Panels 2a and 2b 3.35 – 4.00 – Break 4.00 – 5.20 Panels 3a and 3b 5.20 – 5.30 Closing Remarks 5.30 – 6.30 Reception (Conference Centre) 6.45 – Supper at King’s Head (optional) 10am – 11.20 Welcome from Deborah Jermyn & Catherine Roach and Opening Keynote Professors Karen Randell, Nottingham Trent University and Alexis Weedon, University of Bedfordshire ‘Transatlantic love: distance makes the heart grow fonder - Love and romance across the miles in the work of Elinor Glyn’. BREAK Panels 11.45am – 1.25pm 1a – Small screen, big love: Transatlantic romance on TV Chair: Deborah Jermyn Frances Smith, University College London: ‘Catastrophe: Love in the Glocal City’ Martha Shearer, Universities of Surrey and Royal Holloway, ‘"British people are awful": Anglo-American romance and gentrification in Looking and You're the Worst’ Ashley Morgan, Cardiff School of Art & Design: ‘An Englishman in New York – Sex and Celibacy in Elementary (2012-)’ Caroline Bainbridge, University of Roehampton: ‘Post-feminism as catastrophe? Sharon Horgan and the transatlantic psycho-politics of comic romantic tragedy’ 1b – Transatlantic love in cross-media and cross-cultural contexts Chair: Karen Randell Ted Trost, University of Alabama: '"Imagine there's no countries": John Lennon's Politics of Love’. -

Summer 2004 Through the Covers.” Attempted to Get the Committee to Revoke Its Approval “Do You Know What Means? ‘Crack Them Through of the Topic

St. Mike’s, Wodehouse, and Me: The Great Thesis Handicap did my undergraduate work here at St. Michael’s College BY ELLIOTT MILSTEIN from 1971 to 1976. How an American Jew ended up at a Catholic Canadian University is another story. I must Editor’s note: Elliott Milstein was primary perpetrator of and opening say, however, that planning this convention on the speaker at The Wodehouse Society convention held in Toronto last site of my alma mater, not to mention attending my August. This is Part 1 of Elliott’s talk; tune in to the next issue to read daughter’s graduation ceremonies this past June with his exciting conclusion. all its attendant festivities and speeches, has put me in a nostalgic mood, and all of you are about to become the unwitting victims of this mood. I was introduced to P. G. Wodehouse by my father at the tender age of 12. Having announced to him that I had read everything of interest there was to read (I had finished off the Tom Swift series, you understand), I complained bitterly that there was nothing left in life. He handed me his tattered old (first edition, you understand) Nothing But Wodehouse and instructed me to begin at the end with Leave It to Psmith. Now, if this were a fairy tale, I would tell you that from that moment on I never looked back, but I must be totally honest with you. I found it silly. I did not even get through the first chapter, and I returned it to him. -

Analysis of Intertextuality in the Italian Translations of the Works of P.G

Recibido / Received: 26/06/2016 Aceptado / Accepted: 16/11/2016 Para enlazar con este artículo / To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/MonTI.2017.9.4 Para citar este artículo / To cite this article: VALENTINO, Gabriella. (2017) “Analysis of Intertextuality in the Italian Translations of the Works of P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975) in the Light of the Epistemic Approach.” In: Martínez Sierra, Juan José & Patrick Zabalbeascoa Terran (eds.) 2017. The Translation of Humour / La traducción del humor. MonTI 9trans, pp. 1-24. ANALYSIS OF INTERTEXTUALITY IN THE ITALIAN TRANSLATIONS OF THE WORKS OF P.G. WODEHOUSE (1881-1975) IN THE LIGHT OF THE EPISTEMIC APPROACH Gabriella Valentino [email protected] Swansea University Abstract Research on Humour and Translation studies requires instruments capable to appre- ciate their complex nature. We present here the epistemic approach, a tool especially devised to analyse the translation of humour instances in written fictional text. This approach focuses on the role knowledge plays in creative production and in the process of translating, allowing both translators and researchers to recognize the functions of the stylistic devices employed to convey humour, and to guide and evaluate their rendering in translation. The stylistic device investigated in this study is intertextuality in the works of humourist writer P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975). By means of a case study, its treatment in translation is analysed, comparing five translations of the same novel into Italian, published between 1931 and 1994. Keywords: P.G. Wodehouse. Epistemic approach. Intertextuality. Retranslation. Comic style. primera MonTI 9trans (2017: 1-24). -

Information Sheet Number 9A a Simplified Chronology of PG

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 9a A Simplified Chronology of P G Wodehouse Fiction Revised December 2018 Note: In this Chronology, asterisked numbers (*1) refer to the notes on pages (iv) and (v) of Information Sheet Number 9 The titles of Novels are printed in a bold italic font. The titles of serialisations of Novels are printed in a bold roman font. The titles of Short Stories are printed in a plain roman font. The titles of Books of Collections of Short Stories are printed in italics and underlined in the first column, and in italics, without being underlined, when cited in the last column. Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1901 SC The Prize Poem Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC L’Affaire Uncle John Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Author! Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1902 SC The Pothunters The Pothunters SC The Babe and the Dragon Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC “ The Tabby Terror ” Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Bradshaw’s Little Story Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Odd Trick Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Pothunters SC How Payne Bucked Up Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1903 SC Harrison’s Slight Error Tales of St Austin’s SC How Pillingshot Scored Tales of St Austin’s SC The Manoeuvres of Charteris Tales of St Austin’s SC A Prefect’s Uncle SC The Gold Bat The Gold Bat (1904) SC Tales of St Austin’s A Shocking Affair 1 Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1904 SC The Gold Bat SC The Head of Kay’s The Head -

Novels by P G Wodehouse Appearing in Magazines

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 4 Revised December 2018 Novels by P G Wodehouse appearing in Magazines Of the novels written by P G Wodehouse, the vast majority were serialised in magazines, some appearing in a single issue. The nature of the serialisation changed with time. The early novels were serialised in almost identical form to the published book, but from the mid-1930s there was an increasing tendency for the magazine serialisation to be a condensed version of the novel. In some cases, the condensed version was written first. Attention is drawn in particular to the following titles: The Prince and Betty, which in both the first UK and first US magazine appearances, was based on the UK rather than the very different US book version of the text. A Prince for Hire, which was a serialised novelette based broadly on The Prince and Betty, but completely rewritten in 1931. The Eighteen Carat Kid, which in serial form consisted only of the adventure aspects of The Little Nugget, the love interest being added to ‘flesh out’ the book. Something New, which contained a substantial scene from The Lost Lambs (the second half of Mike) which was included in the American book edition, but not in Something Fresh, the UK equivalent. Leave It To Psmith, the magazine ending of which in both the US and the UK was rewritten for book publication in both countries. Laughing Gas, which started life as a serial of novelette length, and was rewritten for book publication to more than double its original length. -

By the Way Sept 08.Qxd

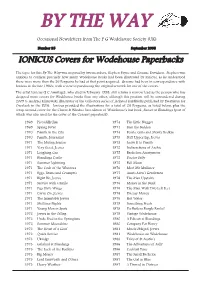

BY THE WAY Occasional Newsletters from The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Number 35 September 2008 IONICUS Covers for Wodehouse Paperbacks The topic for this By The Way was inspired by two members, Stephen Payne and Graeme Davidson. Stephen was anxious to confirm precisely how many Wodehouse books had been illustrated by Ionicus, as he understood there were more than the 56 Penguins he had at that point acquired. Graeme had been in correspondence with Ionicus in the late 1980s, with a view to purchasing the original artwork for one of the covers. The artist Ionicus (J C Armitage), who died in February 1998, still retains a narrow lead as the person who has designed more covers for Wodehouse books than any other, although this position will be surrendered during 2009 to Andrzej Klimowski, illustrator of the Collectors series of jacketed hardbacks published by Everyman (or Overlook in the USA). Ionicus provided the illustrations for a total of 58 Penguins, as listed below, plus the wrap-around cover for the Chatto & Windus first edition of Wodehouse’s last book, Sunset at Blandings (part of which was also used for the cover of the Coronet paperback). 1969 Piccadilly Jim 1974 The Little Nugget 1969 Spring Fever 1974 Sam the Sudden 1970 Psmith in the City 1974 Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin 1970 Psmith, Journalist 1975 Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves 1971 The Mating Season 1975 Leave It to Psmith 1971 Very Good, Jeeves 1975 Indiscretions of Archie 1971 Laughing Gas 1975 Bachelors Anonymous 1971 Blandings Castle 1975 Doctor Sally 1971 Summer Lightning -

Convention Time: August 11–14

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 26 Number 2 Summer 2005 Convention Time: August 11–14 nly two months to go, but it’s not too late to send farewell brunch Oin your registration for The Wodehouse Society’s Fun times that include reading stories with 13th International Convention, Hooray for Hollywood! other Wodehousians, visiting booksellers’ The site of this year’s gathering is Sunset Village on the and Chapters Corner tables, plenty of grounds of the UCLA campus, a beautiful location singing, and most of all cavorting with with easy access to Westwood, the Getty Museum, and fellow Plummies from all over so much more. And if you’re worried about the climate, don’t be: Informed sources tell us that we can expect What—you want to know more? Well, then, how warm, dry weather in Los Angeles in August, making about our speakers, who include: for an environment that will be pleasurable in every way. Brian Taves: “Wodehouse Still can’t make up your mind? Perhaps on Screen: Hollywood and these enticements will sway you: Elsewhere” Hilary & Robert Bruce: “Red A bus tour of Hollywood that Hot Stuff—But Where’s the includes a visit to Paramount Red Hot Staff?” (by Murray Studios Hedgcock) A Clean, Bright Entertainment Chris Dueker: “Remembrance of that includes songs, skits, and Fish Past” The Great Wodehouse Movie Melissa Aaron: “The Art of the Pitch Challenge Banjolele” Chances to win Exciting Prizes Tony Ring: “Published Works on that include a raffle, a Fiendish Wodehouse” Quiz based on Wodehouse’s Dennis Chitty: “The Master’s Hollywood, and a costume Beastly Similes” competition A weekend program that includes Right—you’re in? Good! Then let’s review erudite talks, more skits and what you need to know. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Jeeves in the Offing

JEEVES IN THE OFFING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK P. G. Wodehouse | 208 pages | 12 Sep 2002 | Everyman | 9781841591162 | English | London, United Kingdom Jeeves in the Offing PDF Book I read it in one day, and I agree with Christopher Buckley, who said "It is impossible to be unhappy while reading the adventures of Jeeves and Wooster. Great story - difficult narrator Share on facebook. However, on a few occasions, Bertie mentions picking up a word or phrase from Jeeves that Jeeves was never depicted using earlier in the series. Jan 14, Faith-Anne rated it it was amazing Recommends it for: those who want to laugh. Sometimes I feel the best thing for me to do would be: retire to my 19th century lake house and do nothing for a year other than drink coffee, smoke cigarettes, and read everything P. More Details But his idyll is rudely shattered by Aunt Dahlia who wants him to nobble a racehorse. Jan 27, Pamela Shropshire rated it really liked it Shelves: in-my-library , classics , humour. Meanwhile, Upjohn intends to sue Kipper's paper for libel. Bibliography Short stories Characters Locations Songs. What Ho! PS I would have given it 4. It is wonderful to watch Wodehouse set up situations and then to deny or is it defy? Initially he discovers that Bobbie Wickham is present but more to the point that she has placed an advertisement Jeeves is on holiday in Herne Bay and Bertie Wooster is wondering how he will manage when he is away. New York. Thank You, Jeeves By: P. -

A Source for Alexander Worple

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 34 Number 3 Autumn 2013 A Source for Alexander Worple by Karen Shotting orky Corcoran’s uncle Alexander Worple holds If you’re planning to attend the TWS convention C a special place in the Jeeves and Wooster canon. in Chicago in October, you can find last-minute, Had this Worple been a sort of Cheeryble Brother interesting, and useful information about the event gleefully distributing largesse to a needy nephew, on pages 5, 7, 9, 20, 23, and 24. On those pages you’ll Corky might never have enlisted the aid of his pal find information about group activities, about the Bertie Wooster, who would not have had any reason dress code at the host site (the Union League Club of to utter the fateful words “leave it to Jeeves.” PGW tells Chicago), the Saturday Gala, and many other items. us that it was when he was writing Corky’s story that Jeeves’s qualities dawned upon him. Plum’s artistic soul would not permit him to allow the mentally negligible Bertie or Corky to come up with the creative, brainy solutions to Corky’s predicaments, so he brought back a bit player, a valet by the name of Jeeves from the short story “Extricating Young Gussie,” and gave him his first costarring role with Bertie. For those of you who may be a bit foggy on the details of “The Artistic Career of Corky”/“Leave It to Jeeves,” I will state that Corky finds himself in need of a guide, philosopher, and friend to assist him with a couple of sticky situations.