Analysis of Intertextuality in the Italian Translations of the Works of P.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World by DAVID MCDONOUGH

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 28 Number 2 Summer 2007 Large, Amiable Englishman Who Amused the World BY DAVID MCDONOUGH ecently I read that doing crossword puzzles helps to was “sires,” and the answer was “begets.” In Right Ho, R ward off dementia. It’s probably too late for me (I Jeeves (aka Brinkley Manor, 1934), Gussie Fink-Nottle started writing this on my calculator), but I’ve been giving interrogates G. G. Simmons, the prizewinner for Scripture it a shot. Armed with several good erasers, a thesaurus, knowledge at the Market Snodsbury Grammar School and my wife no more than a phone call away, I’ve been presentations. Gussie, fortified by a liberal dose of liquor- doing okay. laced orange juice, is suspicious of Master Simmons’s bona I’ve discovered that some of Wodehouse’s observations fides. on the genre are still in vogue. Although the Egyptian sun god (Ra) rarely rears its sunny head, the flightless “. and how are we to know that this has Australian bird (emu) is still a staple of the old downs and all been open and above board? Let me test you, acrosses. In fact, if you know a few internet terms and G. G. Simmons. Who was What’s-His-Name—the the names of one hockey player (Orr) and one baseball chap who begat Thingummy? Can you answer me player (Ott), you are in pretty good shape to get started. that, Simmons?” I still haven’t come across George Mulliner’s favorite clue, “Sir, no, sir.” though: “a hyphenated word of nine letters, ending in k Gussie turned to the bearded bloke. -

Downloading the Available Texts from the Gutenberg Site

Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 4.2 (2008): 189-213 189 DOI 10.2478/v10016-008-0013-3 Alan Partington University of Bologna FROM WODEHOUSE TO THE WHITE HOUSE: A CORPUS-ASSISTED STUDY OF PLAY, FANTASY AND DRAMATIC INCONGRUITY IN COMIC WRITING AND LAUGHTER-TALK Abstract In this paper I consider two discourse types, one written and literary, the other spoken and semi-conversational, in an attempt to discover if there are any similarities in the ways in which humour is generated in such apparently diverse forms of communication. The first part of the paper is concerned with the explicitly comic prose of P.G.Wodehouse, whilst in the second part of the paper, we investigate the laughter-talk, defined as the talk preceding and provoking, intentionally or otherwise, an episode of laughter, occurring during press briefings held at the White House during the Clinton era and the subsequent Bush administration. Both studies, by employing corpus analysis techniques together with detailed discourse reading, integrate quantitative and qualitative approaches to the respective data sets. Keywords Humour, stylistics, Wodehouse, press briefings, Corpus-Assisted Discourse Studies. 1. The comic techniques in the prose of P.G. Wodehouse Despite being widely recognised as perhaps the greatest humorous novelist in the English language, and frequently also simply as a great creative genius (Hilaire Belloc called Wodehouse “the best living writer of English”), as Golab notes, “little evidence has been shown to justify this claim,” there is almost no literature “attempting to specify the reasons for Wodehouse’s success as a humorous writer” 190 Alan Partington From Wodehouse to the White House: A Corpus-Assisted Study of … (2004: 35). -

Information Sheet Number 9A a Simplified Chronology of PG

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 9a A Simplified Chronology of P G Wodehouse Fiction Revised December 2018 Note: In this Chronology, asterisked numbers (*1) refer to the notes on pages (iv) and (v) of Information Sheet Number 9 The titles of Novels are printed in a bold italic font. The titles of serialisations of Novels are printed in a bold roman font. The titles of Short Stories are printed in a plain roman font. The titles of Books of Collections of Short Stories are printed in italics and underlined in the first column, and in italics, without being underlined, when cited in the last column. Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1901 SC The Prize Poem Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC L’Affaire Uncle John Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Author! Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1902 SC The Pothunters The Pothunters SC The Babe and the Dragon Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC “ The Tabby Terror ” Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC Bradshaw’s Little Story Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Odd Trick Tales of St Austin’s (1903) SC The Pothunters SC How Payne Bucked Up Tales of St Austin’s (1903) 1903 SC Harrison’s Slight Error Tales of St Austin’s SC How Pillingshot Scored Tales of St Austin’s SC The Manoeuvres of Charteris Tales of St Austin’s SC A Prefect’s Uncle SC The Gold Bat The Gold Bat (1904) SC Tales of St Austin’s A Shocking Affair 1 Published Novel [Collection] Published Short Story [Serial] Relevant Collection [Novel] 1904 SC The Gold Bat SC The Head of Kay’s The Head -

Novels by P G Wodehouse Appearing in Magazines

The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Information Sheet Number 4 Revised December 2018 Novels by P G Wodehouse appearing in Magazines Of the novels written by P G Wodehouse, the vast majority were serialised in magazines, some appearing in a single issue. The nature of the serialisation changed with time. The early novels were serialised in almost identical form to the published book, but from the mid-1930s there was an increasing tendency for the magazine serialisation to be a condensed version of the novel. In some cases, the condensed version was written first. Attention is drawn in particular to the following titles: The Prince and Betty, which in both the first UK and first US magazine appearances, was based on the UK rather than the very different US book version of the text. A Prince for Hire, which was a serialised novelette based broadly on The Prince and Betty, but completely rewritten in 1931. The Eighteen Carat Kid, which in serial form consisted only of the adventure aspects of The Little Nugget, the love interest being added to ‘flesh out’ the book. Something New, which contained a substantial scene from The Lost Lambs (the second half of Mike) which was included in the American book edition, but not in Something Fresh, the UK equivalent. Leave It To Psmith, the magazine ending of which in both the US and the UK was rewritten for book publication in both countries. Laughing Gas, which started life as a serial of novelette length, and was rewritten for book publication to more than double its original length. -

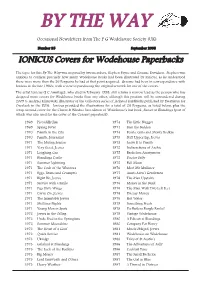

By the Way Sept 08.Qxd

BY THE WAY Occasional Newsletters from The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) Number 35 September 2008 IONICUS Covers for Wodehouse Paperbacks The topic for this By The Way was inspired by two members, Stephen Payne and Graeme Davidson. Stephen was anxious to confirm precisely how many Wodehouse books had been illustrated by Ionicus, as he understood there were more than the 56 Penguins he had at that point acquired. Graeme had been in correspondence with Ionicus in the late 1980s, with a view to purchasing the original artwork for one of the covers. The artist Ionicus (J C Armitage), who died in February 1998, still retains a narrow lead as the person who has designed more covers for Wodehouse books than any other, although this position will be surrendered during 2009 to Andrzej Klimowski, illustrator of the Collectors series of jacketed hardbacks published by Everyman (or Overlook in the USA). Ionicus provided the illustrations for a total of 58 Penguins, as listed below, plus the wrap-around cover for the Chatto & Windus first edition of Wodehouse’s last book, Sunset at Blandings (part of which was also used for the cover of the Coronet paperback). 1969 Piccadilly Jim 1974 The Little Nugget 1969 Spring Fever 1974 Sam the Sudden 1970 Psmith in the City 1974 Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin 1970 Psmith, Journalist 1975 Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves 1971 The Mating Season 1975 Leave It to Psmith 1971 Very Good, Jeeves 1975 Indiscretions of Archie 1971 Laughing Gas 1975 Bachelors Anonymous 1971 Blandings Castle 1975 Doctor Sally 1971 Summer Lightning -

Convention Time: August 11–14

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 26 Number 2 Summer 2005 Convention Time: August 11–14 nly two months to go, but it’s not too late to send farewell brunch Oin your registration for The Wodehouse Society’s Fun times that include reading stories with 13th International Convention, Hooray for Hollywood! other Wodehousians, visiting booksellers’ The site of this year’s gathering is Sunset Village on the and Chapters Corner tables, plenty of grounds of the UCLA campus, a beautiful location singing, and most of all cavorting with with easy access to Westwood, the Getty Museum, and fellow Plummies from all over so much more. And if you’re worried about the climate, don’t be: Informed sources tell us that we can expect What—you want to know more? Well, then, how warm, dry weather in Los Angeles in August, making about our speakers, who include: for an environment that will be pleasurable in every way. Brian Taves: “Wodehouse Still can’t make up your mind? Perhaps on Screen: Hollywood and these enticements will sway you: Elsewhere” Hilary & Robert Bruce: “Red A bus tour of Hollywood that Hot Stuff—But Where’s the includes a visit to Paramount Red Hot Staff?” (by Murray Studios Hedgcock) A Clean, Bright Entertainment Chris Dueker: “Remembrance of that includes songs, skits, and Fish Past” The Great Wodehouse Movie Melissa Aaron: “The Art of the Pitch Challenge Banjolele” Chances to win Exciting Prizes Tony Ring: “Published Works on that include a raffle, a Fiendish Wodehouse” Quiz based on Wodehouse’s Dennis Chitty: “The Master’s Hollywood, and a costume Beastly Similes” competition A weekend program that includes Right—you’re in? Good! Then let’s review erudite talks, more skits and what you need to know. -

Wodehouse in Wonderland by Robert Mccrum

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 37 Number 1 Spring 2016 Wodehouse in Wonderland by Robert McCrum Writer and noted Wodehouse biographer Robert McCrum spoke at the Pseattle convention about Wodehouse’s ability to react with humor to any event, even the most extreme and painful, including his experiences during and after World War II. I personally was very moved when I considered Wodehouse’s innermost feeling during those last decades of his life. Thanks to Robert for giving us permission to share this fascinating study with the entire society. or more than twenty years I’ve been hearing about Fthese Wodehouse conventions. Now, finally, I get it. This is probably the most fun you can have without being arrested, an offbeat symposium of sheer delight. So first, my thanks to The Wodehouse Society for Writer Robert McCrum its kind invitation, with a special thank-you to Tom Smith. Since we first met in 2002, Tom has now become Nor should we overlook Stanley Featherstonehaugh a doctor (of letters) as well as a major. Which just goes Ukridge, that shambolic sponger and con man, or to show the therapeutic powers of the PGW regime. Lord Emsworth and his peerless prize pig, Empress It’s been about ten years since I completed my study of Blandings. Or Mr. Mulliner. Or—well, we all have of Wodehouse [Wodehouse: A Life], an unforgettable our favorites. This is about to be a golden season for experience with so many happy memories. But life since Wodehouse anniversaries, and a jubilee for the world’s completing that work has been wonderful, too. -

Piccadilly Jim by P.G. Wodehouse

Piccadilly Jim By P.G. Wodehouse 1 CHAPTER I A RED-HAIRED GIRL The residence of Mr. Peter Pett, the well-known financier, on Riverside Drive is one of the leading eyesores of that breezy and expensive boulevard. As you pass by in your limousine, or while enjoying ten cents worth of fresh air on top of a green omnibus, it jumps out and bites at you. Architects, confronted with it, reel and throw up their hands defensively, and even the lay observer has a sense of shock. The place resembles in almost equal proportions a cathedral, a suburban villa, a hotel and a Chinese pagoda. Many of its windows are of stained glass, and above the porch stand two terra-cotta lions, considerably more repulsive even than the complacent animals which guard New York's Public Library. It is a house which is impossible to overlook: and it was probably for this reason that Mrs. Pett insisted on her husband buying it, for she was a woman who liked to be noticed. Through the rich interior of this mansion Mr. Pett, its nominal proprietor, was wandering like a lost spirit. The hour was about ten of a fine Sunday morning, but the Sabbath calm which was upon the house had not communicated itself to him. There was a look of exasperation on his usually patient face, and a muttered oath, picked up no doubt on the godless Stock Exchange, escaped his 2 lips. "Darn it!" He was afflicted by a sense of the pathos of his position. It was not as if he demanded much from life. -

The Early Days of the Wodehouse Society by Len Lawson Past TWS President Len Lawson Gave This Presentation at the June 2009 Convention in St

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 31 Number 1 Spring 2010 The Early Days of The Wodehouse Society by Len Lawson Past TWS President Len Lawson gave this presentation at the June 2009 convention in St. Paul. We’re grateful that Len has helped preserve this historical information and has shared it with us so entertainingly. he Wodehouse Society was founded by the gentleman you see Tpictured here, Captain William “Bill” W. Blood, USAF Retired. Not the best photo, but as you read in the caption, “The brilliance of his personality causes a lighting problem for photographers . .” The society was born with the meeting of Bill Blood and Franklin Axe (date unknown, probably 1979 or 1980). They met at an auction house (location unknown, probably near Doylestown, Pennsylvania) that often handled books. Frank’s wife Edna was looking for Wodehouse books for him when she ran into Bill Blood, also looking for Wodehouse books. Bill asked Edna to bring Frank along next time so they could talk about Wodehouse. She did and they did. Frank and Bill had a great time talking about Wodehouse. Bill asked if Frank would like to meet like this once a month, perhaps with more PGW devotees. Frank said, “Of course.” Somewhere along the way Bill suggested that they start a Wodehouse society, in fact, The Wodehouse Society. Since Bill agreed to do all the work, Frank said it was a great idea. Bill started by writing letters everywhere and placing a few advertisements. He wrote a letter to the editor of the New Hope Gazette, published a few miles from Bill Blood’s Doylestown in eastern Pennsylvania. -

Autumn 2004 Wodehouse in America N His New Biography of P

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 25 Number 3 Autumn 2004 Wodehouse in America n his new biography of P. G. Wodehouse, Robert IMcCrum writes: “On a strict calculation of the time Wodehouse eventually spent in the United States, and the lyrics, books, stories, plays and films he wrote there, to say nothing of his massive dollar income, he should be understood as an American and a British writer.” The biography Wodehouse: A Life will be published in the United States in November by W.W. Norton & Co., and will be reviewed in the next issue of Plum Lines. McCrum’s book presents the American side of Wodehouse’s life and career more fully than any previous work. So with the permission of W.W. Norton, we present some advance excerpts from the book concerning Plum’s long years in America. First trip Wodehouse sailed for New York on the SS St. Louis on 16 April 1904, sharing a second-class cabin with three others. He arrived in Manhattan on 25 April, staying on Fifth Avenue with a former colleague from the bank. Like many young Englishmen, before and since, he found it an intoxicating experience. To say that New York lived up to its advance billing would be the baldest of understatements. ‘Being there was like being in heaven,’ he wrote, ‘without going to all the bother and expense of dying.’ ‘This is the place to be’ Wodehouse later claimed that he did not intend to linger in America but, as in 1904, would just take a perhaps he had hoped to strike gold. -

P. G. Wodehouse Conquers Sweden by Bengt Malmberg

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 35 Number 3 Autumn 2014 P. G. Wodehouse Conquers Sweden by Bengt Malmberg n 1964, in a letter to Georg Svensson, chief editor of Ithe publishing house Bonniers, Wodehouse wrote: I am glad of this opportunity to tell you how grateful I am to you for all the trouble you have taken to put me over with the Swedish public. I am so intensely spiritual that money means nothing to me, but I must confess that the cheques that Mr. Watt sends me for my Swedish sales do give me a gentle thrill. Whenever a book of mine is going what my publisher calls “slowly” in the USA, I cheer up because I know that everything is going to be all right in Sweden, thanks to you. In 2012 we celebrated 100 years of Wodehouse in the Swedish language. In October 1912 the weekly magazine Allers Familj-Journal published “Ruth in Exile” as “Ruth i landsflykt” only three months after the original had been published in Strand (July 1912). It Bengt Malmberg, one of many Swedish fans of P. G. Wodehouse was possibly the first translated Wodehouse story in the world. A century later it was republished in the Swedish magazines. Sweden has continued to be at the forefront Wodehouse Society’s yearbook Jeeves 2012. In January of translation of Wodehouse, with the Swedish 1913 the daily newspaper Nerikes Alle-handa translated translation usually being the first or second translation and published “Spådomen” (“Pots o’ Money,” Strand, of fifty Wodehouse novels over the years. -

Meet Mr. Mulliner What This Story Is About

\ MEET MR. MULLINER WHAT THIS STORY IS ABOUT This book provides laughter, laughter all the way. ]\Ieet Mr. Mulliner and the spirits soa r upwards. He relates some truly remark- able adventures. He is blessed, too, with a bevy of priceless relatives who keep the ball of fun rolling in no uncertain fashion. There is nephew Lancelot, cousin Clarence, the bulb-squeezer or photographer, nephew George, cursed with a terrible stammer, and brother Wilfred who was clean bowled over by Miss Angela Purdue. In this bright company no one can fail to be amused. BY THE SAME AUTHOR CARRY ON, JEEVES .. 3S. 6d. net. LEAVE IT TO PSMITH 2S. 6d. net. UKKIDGE 2S. 6d. net. THE INIMITABLE JEEVES 2S. 6d. net. THE GIRL ON THE BOAT 2S. 6d. net. JILL THE RECKLESS .. 2S. 6d. net. A DAMSEL IN DISTRESS 23. 6d. net. LOVE AMONG THE CHICKENS 2S. 6d. net. A GENTLEMAN OF LEISURE 2S. 6d. net. INDISCRETIONS OF ARCHIE 2S, 6d. net. PICCADILLY JIM 28. 6d. net. THE ADVENTURES OF SALLY 2S. 6d. net. THE CLICKING OF CUTHBERT 2S. 6d. net. THE COMING OF BILL 2S. 6d. net. THE HEART OF A GOOF 2S. 6d. net. MEET MR. MULLINER BY P. G. WODEHOUSE HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED 3 YORK STREET ST. JAMES'S LONDON S.W.I « © ^ 'g 30,000 copies Printed in Great Britain hy Willi am Clowes and Sons, Limited, London and Beccles. TO THE EARL OF OXFORD AND ASQUITH CONTENTS I. The Truth about George 7 II. A Slice of Life 39 III. Mulliner's Buck-u-Uppo 68 IV.