The Max Headroom Project.Fm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad Radio 106,2

#WhoWeAre To become the largest Music Media and Services organization in the countries we operate, providing services and products which cover all communication & media platforms, satisfying directly and efficiently both our client’s and our audience’s needs, maintaining at the same time our brand's creative and subversive character. #MISSION #STRUCTURE NEW MEDIA TV EVENTS RADIO WEB INTERNATIONAL & SERVICES MAD 106,2 Mad TV www.mad.gr DIGITAL VIDEO MUSIC MadRADIO Mad TV CYPRUS GREECE MARKETING AWARDS Mad HITS/ CONTENT Mad TV MADWALK 104FM SOCIAL MEDIA OTE Conn-x SERVICES ALBANIA Mad GREEKζ/ MAD MUSIC ANTENNA EUROSONG NOVA @NOVA SATELLITE MAD PRODUCTION NORTH STAGE Dpt FESTIVAL YouTube #TV #MAD TV GREECE • Hit the airwaves on June 6th, 1996 • One of the most popular music brands in Greece*(Focus & Hellaspress) • Mad TV has the biggest digital database of music content in Greece: –More than 20.000 video clips –250.000 songs –More than 1.300 hours of concerts and music documentaries –Music content database with tens of thousands music news, biographical information –and photographic material of artists, wallpapers, ring tones etc. • Mad TV has deployed one of the most advanced technical infrastructures and specialized IT/Technical/ Production teams in Greece. • Mad TV Greece is available on free digital terrestrial, cable, IPTV, satellite and YouTube all over Greece. #PROGRAM • 24/7 youth program • 50% International + 50% Greek Music • All of the latest releases from a wide range of music genres • 30 different shows/ week (21 hours of live -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

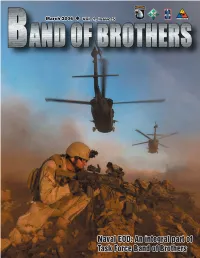

An Integral Part of Task Force Band of Brothers

March 2006 Vol. 1, Issue 5 Naval EOD: An integral part of Task Force Band of Brothers Two Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division sit on stage for a comedy skit with actress Karri Turner, most known for her role on the television series JAG, and comedians Kathy Griffin, star of reality show My Life on the D List and Michael McDonald, star of MAD TV. The three celebrities performed a number of improv skits for Soldiers and Airmen of Task Force Band of Brothers at Contingency Operating Base Speicher in Tikrit, Iraq, Mar. 17, as part of the Armed Forces Entertainment tour, “Firing at Will.” photo by Staff Sgt. Russell Lee Klika Inside... In every issue... Hope in the midst of disaster Page 5 Health and Fitness: Page 9 40 Ways to Eat Better Bastogne Soldiers cache in their tips Page 6-7 BOB on the FOB Page 20 Combat support hospital saves lives Page 8 Your new favorite cartoon! Aviation Soldiers keep perimeter safe Page 10 Hutch’s Top 10 Page 21 Fire Away! Page 11 On the cover... Detention facility goes above and beyond Page 12 Soldier writes about women’s history Page 13 U.S. Navy Explosive Or- Project Recreation: State adopts unit Page 16-17 dinance Disposal tech- nician Petty Officer 2nd Albanian Army units work with Page 18-19 Class Scott Harstead and Soldiers from the Coalition Forces in war on terrorism 1st Brigade Combat Team, 1st Armored Di- FARP guys keep helicopters in fight Page 22 vision dismount a UH- 60 Blackhawk from the Mechanics make patrols a success Page 23 101st Airborne Division during an Air Assault in the Ninevah Province, Soldier’s best friend Page 24 Iraq, Mar. -

Local Public Health Office to Close

SERVING EASTERN SHASTA, NORTHERN LASSEN, WESTERN MODOC & EASTERN SISKIYOU COUNTIES 70 Cents Per Copy Vol. 45 No. 43 Burney, California Telephone (530) 335-4533 FAX (530) 335-5335 Internet: im-news.com E-mail: [email protected] JANUARY 7, 2004 Local public health offi ce to close BY MEG FOX the state’s Vehicle License Fee who have been notifi ed about their “Our staff traveled to nine com- programs and services. Six public health employees will (VLF). But the money to make up jobs are Community Health Advo- munities to do the fl u clinics,” said The Burney regional offi ce par- be laid off and access to numerous the state’s $10.5 billion defi cit had to cate Claudia Woods, Community Moore, adding that she doesn’t ticipated on the Intermountain Injury local services will end when Shasta come from somewhere and public Organizer Laura Thompson, Com- know how many, if any, fl u clinics Prevention Coalition, the Physical County Public Health closes the health is one of several targets. munity Health Advocates Manuel the county will be able to provide Activity and Nutrition team (PANT), doors of the Burney Regional offi ce “Shasta County Public Health is Meza and Kenia Howard, and Medi- locally. Intermountain Breastfeeding Coali- on Feb. 20. losing about a third of its funding cal Services Clerk Jennifer Cearley. “It’s not looking good,” she said. tion, Intermountain Area Domestic “We fi nally got more services up until the state fi nds another way to The department plans to retain The Burney staff worked with the Violence Coordinating Council, here and now they’re going away,” pay for local public health,” Moore Public Health Nurse David Moe- schools to improve physical activ- and Intermountain Hispanic/Latino said Community Development said. -

Spring 2007 Newsletter

Dance Studio Art Create/Explore/InNovate DramaUCIArts Quarterly Spring 2007 Music The Art of Sound Design in UCI Drama he Drama Department’s new Drama Chair Robert Cohen empa- a professor at the beginning of the year, graduate program in sound sized the need for sound design initia- brings a bounty of experience with him. design is a major step in the tive in 2005 as a way to fill a gap in “Sound design is the art of provid- † The sound design program Tdepartment’s continuing evolution as the department’s curriculum. “Sound ing an aural narrative, soundscape, contributed to the success of Sunday in The Park With George. a premier institution for stagecraft. design—which refers to all audio reinforcement or musical score for generation, resonation, the performing arts—namely, but not performance and enhance- limited to, theater,” Hooker explains. ment during theatrical or “Unlike the recording engineer or film film production—has now sound editor, we create and control become an absolutely the audio from initial concept right vital component” of any down to the system it is heard on.” quality production. He spent seven years with Walt “Creating a sound Disney Imagineering, where he designed design program,” he con- sound projects for nine of its 11 theme tinued, “would propel UCI’s parks. His projects included Cinemagique, Drama program—and the an interactive film show starring actor collaborative activities of Martin Short at Walt Disney Studios its faculty—to the high- Paris; the Mermaid Lagoon, an area fea- est national distinction.” turing several water-themed attractions With the addition of at Tokyo Disney Sea; and holiday overlays Michael Hooker to the fac- for the Haunted Mansion and It’s a Small ulty, the department is well World attractions at Tokyo Disneyland. -

Enjoy a Free Evening of Comedy in New York City's Central Park This

Enjoy a Free Evening of Comedy in New York City's Central Park This Summer! The Third Annual 'COMEDY CENTRAL Park' Live from SummerStage Starring Gabriel Iglesias with Special Guest Pablo Francisco Takes Place Rain or Shine on Friday, June 19 at 8:00 P.M. "COMEDY CENTRAL Park" Is One Of 31 Free Programs Offered During The 2009 Central Park SummerStage Season Through The City Parks Foundation In New York City The First 3,000 Attendees Will Receive A Complimentary, Reusable Shopping Bag Courtesy Of The Network's Pro-Social Initiative AddressTheMess NEW YORK, June 8 -- No two drink minimum necessary at this venue, it's entirely free. On Friday, June 19, New York City's Central Park turns into "COMEDY CENTRAL Park," a night of free stand-up comedy Live from SummerStage. The outdoor venue is located at mid-Central Park (near the Fifth Avenue & 72nd Street entrance) with doors opening at 7:00 p.m. and the show starting at 8:00 p.m. This is the third consecutive year COMEDY CENTRAL has participated in this hugely successful event. This year's presentation of "COMEDY CENTRAL Park" will feature comedian Gabriel Iglesias, who blends his impeccable voice skills with an uncanny knack for animated comedic storytelling that bring his issues to life, and special guest Pablo Francisco, who has an unbelievable ability to physically morph himself into movie stars, singers, friends, family, and a multitude of nationalities. Outback Steakhouse and All-Natural Snapple are the proud sponsors of "COMEDY CENTRAL Park." Iglesias's talent on stage has earned him several television appearances. -

The BG News April 2, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-2-1999 The BG News April 2, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 2, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6476. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. .The BG News mostly cloudy New program to assist disabled students Office of Disability Services offers computer program that writes what people say However, he said, "They work together," Cunningham transcripts of students' and ities, so they have an equal By IRENE SHARON (computer programs] are far less said. teachers' responses. This will chance of being successful. high: 69 SCOTT than perfect." Additionally, the Office of help deaf students to participate "We try to minimize the nega- The BG News Also, in the fall they will have Disability Services hopes to start in class actively, he said. tives and focus on similarities low: 50 The Office of Disability Ser- handbooks available for teachers an organization for disabled stu- Several disabled students rather than differences," he said. vices for Students is offering and faculty members, so they dents. expressed contentment over the When Petrisko, who has pro- additional services for the dis- can better accommodate dis- "We are willing to provide the services that the office of disabil- found to severe hearing loss, was abled community at the Univer- abled students. -

AUTHOR Braddlee TITLE Intertextuality and Television Discourse: the Max Headroom Story

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 310 462 CS 506 795 AUTHOR Braddlee TITLE Intertextuality and Television Discourse: The Max Headroom Story. PUB DATE May 89 NOTE 27p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association (38th, New Orleans, LA, May 29-June 2, 1988). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; Discourse Analysis; Higher Education; Mass Media; Mass Media Effects; *Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programing (Broadcast); *Reader Text Relationship; Television Research; *Television Viewing; Text Structure IDENTIFIERS Intertextuality; *Max Headroom ABSTRACT Max Headroom, the computer-generated media personality, presents a good opportunity for an investigation of the degree of intertextuality in television. Max combines narrative genres (science fiction and film noir), television program types (prime-time episodic narrative, made-for-TV movie, talkshows), advertising and programming, and electronic and print media. Analysis of one channel of discourse, commercials and advertising, shows that neither advertisers nor textual theorists can rest safely on their assumptions. The text involved here is complex in the very sense that culture itself is complex, and readings of media that reduce complexity to a simplistic ideological positioning of readers are reductive and based on an overprivileging of dominance over the intelligence of viewers, and their power to expose and exploit contradictory textual elements. By over-emphasizing the hegemonic and deemphasizing the emancipatory or oppositional, injustice is done to both the complexity of texts, and their potential for encouraging critical positionings among readers. Only through empirical investigation of individuals' readings in a consistent and systematic fashion will it be possible to determine the relationships between viewers and texts. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Saturday and Sunday Movies

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, May 28, 2004 5 abigail your help, Abby — it’s been an aw- dinner in the bathroom with her. I behavior is inappropriate. Your parents remember leaving me home Co-worker ful burden. — OLD-FASHIONED find his behavior questionable and daughter is old enough to bathe with- alone at that age, but that was 24 van buren IN BOULDER have asked him repeatedly to allow out supervision and should do so. years ago. I feel things are too dan- DEAR OLD-FASHIONED: Talk her some privacy. Nonetheless, he You didn’t mention how physically gerous these days. creates more to the supervisor privately and tell continues to “assist her” in bathing developed she is, but she will soon Is there an age when I can leave •dear abby him or her what you have told me. by adding bath oil to the water, etc. be a young woman. Your husband’s them home alone and know that all work for others Say nothing to Ginger, because that’s Neither my husband nor my daugh- method of “lulling” her to sleep is is OK? — CAUTIOUS MOM IN DEAR ABBY: I work in a large, breaks, sometimes even paying her the supervisor’s job — and it will ter thinks anything is wrong with this also too stimulating for both of them. KANSAS open office with five other people. bills and answering personal corre- only cause resentment if you do. behavior — so what can I do? Discuss this with your daughter’s DEAR CAUTIOUS MOM: I’m We all collaborate on the same spondence on company time. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

ARDEN MYRIN Theatrical Resume

ARDEN MYRIN Page 1 of 2 ARDEN MYRIN FILM WRONG COPS Independent Dir: Quentin Dupieux BACHELORETTE Weinstein Company Dir: Leslye Headland WRONG Independent Dir: Quentin Dupieux MORNING GLORY Paramount Pictures Dir: Roger Michell A LITTLE HELP Independent Dir: Michael J. Weithorn THE INFORMANT: A TRUE STORY Warner Bros. Dir: Steven Soderbergh THE LUCKY ONES Lionsgate Dir: Neil Burger EVAN ALMIGHTY Universal Dir: Tom Shadyac KINSEY Fox Searchlight Dir: Bill Condon CHRISTMAS WITH THE KRANKS Columbia Pictures Dir: Joe Roth HEART OF THE BEHOLDER Independent Dir: Ken Tipton DRY CYCLE Independent Dir: Isaac H. Eaton AUTOFOCUS Sony Pictures Classics Dir: Paul Schrader HIGHWAY New Line Cinema Dir: James Cox BUBBLE BOY Buena Vista Dir: Blair Haynes WHAT WOMEN WANT Paramount Pictures Dir: Nancy Meyers DECONSTRUCTING HARRY Fine Line Features Dir: Woody Allen THE IMPOSTERS Fox Searchlight Dir: Stanley Tucci I THINK I DO Independent Dir: Brian Sloan TELEVISION CHELSEA LATELY E! Network Regular Panelist HOLE TO HOLE Adult Swim Series Regular/Creator ORANGE IS THE NEW BLACK Netflix Guest Star INSIDE AMY SCHUMER Comedy Central Guest Star NEXT CALLER NBC Potential Recurring SUBURGATORY WB/ABC Recurring PSYCH USA Recurring UNTITLED ARDEN MYRIN PROJECT MTV/Pilot Series Regular/Creator HUNG HBO Guest Star GARFUNKEL AND OATES HBO/Pilot Recurring DELOCATED Adult Swim Guest Star PSYCH USA Recurring HOT IN CLEVELAND TVLAND Guest Star PARTY DOWN Starz Guest Star ROYAL PAINS USA Guest Star MICHAEL AND MICHAEL HAVE ISSUES Comedy Central Recurring MAD TV FBC Series Regular ON THE SPOT WB Series Regular WHAT'S UP PETER FUDDY? FBC/Pilot Series Regular WORKING NBC Series Regular THE ROYALE AMC Series Regular UNTITLED HBO NBA PROJECT HBO/Pilot Guest Star GILMORE GIRLS WB Guest Star RENO 911 Comedy Central Guest Star FRIENDS NBC Guest Star STAND-UP COMEDY THE PARTY MACHINE Union Hall, NYC Writer/Performer STRAIGHT OUTTA LIL' COMPTON HBO Workspace Writer/Performer STAND-UP COMEDY Various Writer/Performer IMPROV UCB/Groundlings/IOwest Los Angeles/NYC Performer Page 2 of 2 .