AUTHOR Braddlee TITLE Intertextuality and Television Discourse: the Max Headroom Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

(And Holmes Related) Films and Television Programs

Checklist of Sherlock Holmes (and Holmes related) Films and Television Programs CATEGORY Sherlock Holmes has been a popular character from the earliest days of motion pictures. Writers and producers realized Canonical story (Based on one of the original 56 s that use of a deerstalker and magnifying lens was an easily recognized indication of a detective character. This has led stories or 4 novels) to many presentations of a comedic detective with Sherlockian mannerisms or props. Many writers have also had an Pastiche (Serious storyline but not canonical) p established character in a series use Holmes’s icons (the deerstalker and lens) in order to convey the fact that they are acting like a detective. Derivative (Based on someone from the original d Added since 5-22-14 tales or a descendant) The listing has been split into subcategories to indicate the various cinema and television presentations of Holmes either Associated (Someone imitating Holmes or a a in straightforward stories or pastiches; as portrayals of someone with Holmes-like characteristics; or as parody or noncanonical character who has Holmes's comedic depictions. Almost all of the animation presentations are parodies or of characters with Holmes-like mannerisms during the episode) mannerisms and so that section has not been split into different subcategories. For further information see "Notes" at the Comedy/parody c end of the list. Not classified - Title Date Country Holmes Watson Production Co. Alternate titles and Notes Source(s) Page Movie Films - Serious Portrayals (Canonical and Pastiches) The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes 1905 * USA Gilbert M. Anderson ? --- The Vitagraph Co. -

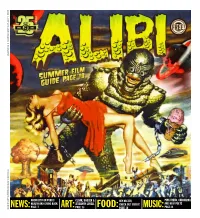

Ad Pages Template

VOLUME 26 | ISSUE 19 | MAY 11-17, 2017 | FREE | 2017 11-17, | MAY 19 ISSUE | 26 VOLUME ARCHULETA ON PUBLIC CLOAK, DAGGER & HEY MISTER, PINK FREUD, CHICHARRA HEALTH AND GIVING BACK JESSAMYN LOVELL CHECK OUT SISTER! AND DEAF POETS PAGE: 7 PAGE: 13 PAGE 24 MAKIN’ OUT IN THE BACK ROW SINCE 1992 SINCE ROW BACK THE IN OUT MAKIN’ PAGE: 16 MAY 11-17, 2017 WEEKLY ALIBI [3] alibi VOLUME 26 | ISSUE 19 | MAY 11-17, 2017 EDITORIAL MANAGING EDITOR/COPY EDITOR: Renee Chavez (ext. 255) [email protected] FILM EDITOR: Devin D. O’Leary (ext. 230) [email protected] MUSIC EDITOR/NEWS EDITOR: August March (ext. 245) [email protected] ARTS/LIT EDITOR: Maggie Grimason (ext. 239) [email protected] CALENDARS EDITOR: Children’s Choice is oering Megan Reneau (ext. 260) [email protected] STAFF WRITER: WEEK-LONG Joshua Lee (ext. 243) [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR: SUMMER CAMPS Samantha Carrillo (ext. 223) [email protected] in Music, Science, Puppets, Sports, CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Cecil Adams, Gustavo Arellano, Robin Babb, Bob eater, Flash Mob, Dance, Film, Brezsny, Carolyn Carlson, Doug Cohen, Desmond Fox, Taylor Grabowsky, Kristi D. Lawrence, Sara MacNeil, Percussion, and Harry Potter! Hosho McCreesh, Geoffrey Plant, Mikee Riggs PRODUCTION EDITORIAL DESIGNER: Valerie Serna (ext.254) [email protected] GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Jesse Philips (ext.240) [email protected] STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER: Eric Williams [email protected] CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS: Max Cannon, Michael Ellis, Jodie Herrera, KAZ, Ryan North, Jen Sorensen Check out: SALES SALES DIRECTOR: Tierna Unruh-Enos (ext. 248) [email protected] childrens-choice.org ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES: Kittie Blackwell (ext. -

Computer Algorithms As Persuasive Agents: the Rhetoricity of Algorithmic Surveillance Within the Built Ecological Network

COMPUTER ALGORITHMS AS PERSUASIVE AGENTS: THE RHETORICITY OF ALGORITHMIC SURVEILLANCE WITHIN THE BUILT ECOLOGICAL NETWORK Estee N. Beck A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Kristine Blair, Advisor Patrick Pauken, Graduate Faculty Representative Sue Carter Wood Lee Nickoson © 2015 Estee N. Beck All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair, Advisor Each time our students and colleagues participate online, they face invisible tracking technologies that harvest metadata for web customization, targeted advertising, and even state surveillance activities. This practice may be of concern for computers and writing and digital humanities specialists, who examine the ideological forces in computer-mediated writing spaces to address power inequality, as well as the role ideology plays in shaping human consciousness. However, the materiality of technology—the non-human objects that surrounds us—is of concern to those within rhetoric and composition as well. This project shifts attention to the materiality of non-human objects, specifically computer algorithms and computer code. I argue that these technologies are powerful non-human objects that have rhetorical agency and persuasive abilities, and as a result shape the everyday practices and behaviors of writers/composers on the web as well as other non-human objects. Through rhetorical inquiry, I examine literature from rhetoric and composition, surveillance studies, media and software studies, sociology, anthropology, and philosophy. I offer a “built ecological network” theory that is the manufactured and natural rhetorical rhizomatic network full of spatial, material, social, linguistic, and dynamic energy layers that enter into reflexive and reciprocal relations to support my claim that computer algorithms have agency and persuasive abilities. -

The Art of Noise the Best of the Art of Noise Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Art Of Noise The Best Of The Art Of Noise mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: The Best Of The Art Of Noise Country: Europe Released: 1988 Style: Leftfield, Downtempo, Synth-pop, Experimental, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1752 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1875 mb WMA version RAR size: 1745 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 426 Other Formats: MP4 MP3 AA MMF MP1 MIDI RA Tracklist Hide Credits Art Works 12" 1 Opus 4 2:00 2 Beat Box (Diversion One) 8:33 3 Moments In Love 7:00 4 Close (To The Edit) 5:41 Peter Gunn (The Twang Mix) 5 7:30 Featuring – Duane Eddy Paranoimia 6 6:40 Featuring – Max Headroom 7 Legacy 8:20 8 Dragnet '88 (From The Motion Picture Dragnet) 7:15 Kiss (The AON Mix) 9 8:09 Featuring – Tom Jones 10 Something Always Happens 2:28 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – China Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – China Records Ltd. Marketed By – Polydor Records Ltd. Distributed By – Polydor Records Ltd. Published By – Warner Bros. Music Ltd. Published By – Perfect Songs Ltd. Published By – Unforgettable Songs Ltd. Published By – RCA Music Ltd. Published By – Carlin Music Corp. Published By – Controversy Music Published By – Copyright Control Published By – BMG Music Publishing Ltd. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Zang Tuum Tumb Licensed From – Island Licensed From – ZTT Credits Composed By – Dudley* (tracks: 1 to 4, 6, 7, 10), Langan* (tracks: 1 to 4, 7, 10), Mancini* (tracks: 5), Jeczalik* (tracks: 1 to 4, 6, 7, 10), Morley* (tracks: 2 to 4), Prince (tracks: 9), Horn* (tracks: 2 to 4), Schumann* (tracks: 8) Design – Ryan Art Photography By [Sea Scape] – Paul Wakefield Producer, Arranged By – Anne Dudley (tracks: 1, 2, 5 to 10), Gary Langan (tracks: 1, 2, 5 to 7, 10), J. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

The Dr. Demento Show #98-24 - June 14, 1998

The Dr. Demento Show #98-24 - June 14, 1998 --- Playlist --- Topic: 1986 Playlist Generated on 09/26/21 by www.madmusic.com Werecow - Flippy T. Fishead & The Mighty Ground Beeves Kill Barney - P. H. Fred My Dad's A Wonderful Guy - Mr. Zipp & Clint My Father's Top Drawer - Peter Alsop Eat All The Old People - No Time Ghost Chickens In The Sky - Sean Morey God Bless The U. F. O. - Capitol Steps Hey, Godzilla - Whimsical Will It's Not Nice To Fool Mother Nature - Dan Murphy Stop Talking About Comic Books Or I'll Kill You - Ookla the Mok Comix Song #2 - The Vestibules Do The Cartman - P. H. Fred We Burned The Christmas Tree - Pete Chaston & Walt Groditski Let's Make The Water Turn Black - The Mothers of Invention Dog With Plastic Stomach - The Yuh-uh-uh-uhs Small Brown Hill - John Kubilus Happy Boy - The Beat Farmers Ukrainian Uranium Bread - Tim Cavanagh Roaches - Bobby Jimmy & The Critters Jane, Get Me Off This Crazy Thing! (Prime Time Radio Mix) - The Tee Vee Toons Master Mix I Do The Watusi - Howie Mandel Addicted To Spuds - "Weird Al" Yankovic Rock Me Jerry Lewis - Tri 5 f/ Mike & Bud (Mike Elliott & Bud LaTour) Paranoimia - The Art Of Noise w/ Max Headroom A Medley Of Beatles' Tunes - Father Guido Sarducci #5 - First Redneck On The Internet - Cledus T. Judd (w/ Buck Owens) #4 - Talking Again - Henry Phillips f/ Edie Magoun #3 - South Park Junkie - Sudden Death #2 - Defenders Of Marriage - Roy Zimmerman #1 - Star Trekkin' - The Firm - Talking Again (Bonus Track) - Henry Phillips f/ Edie Magoun Next week: the great outdoors. -

'N' Andy: the Colour Blind Ideology in Video Game Voice Acting

Document generated on 09/30/2021 2:10 p.m. Loading The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Avatar 'n' Andy The Colour Blind Ideology in Video Game Voice Acting Philip Miletic Volume 13, Number 21, Summer 2020 Article abstract Despite recent criticisms that call out blackface in video game voice acting, the URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1071450ar term “blackface” was and still is seldomly used to describe the act of casting DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1071450ar white voice actors as characters of colour. As a result, the act of blackface in video game voice acting still occurs because of colorblind claims surrounding See table of contents the digital medium and culture of games. In this paper, I position blackface in video game voice acting within a technological and cultural history of oral blackface and white sonic norms. I focus on three time periods: the Publisher(s) Intellivision Intellivoice and the invention of a "universal" voice in video games; early American radio in the 1920s-1930s and the national Canadian Game Studies Association standardization of voice; and colorblind rhetoric of contemporary game publishers/devs and voice actors. ISSN 1923-2691 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Miletic, P. (2020). Avatar 'n' Andy: The Colour Blind Ideology in Video Game Voice Acting. Loading, 13(21), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.7202/1071450ar Copyright, 2020 Philip Miletic This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

Movies on TV This Week (Complete Listings for the Week of June 6

Movies on TV This Week (complete listings for the week of June 6 - June 12, 2010 ) A detective and a Secret Service agent investigate nanny must deal with her employer’s spoiled video store’s obliterated inventory. (PG-13) Black Cadillac ›› ’03 Suspense. Randy an abduction. (2:00) (FX) Sat. 8:30 a.m. children. ‘G’ (2:00) (FAMILY) Sat. 6 a.m. (1:41) (MMAX) Thu. 4:30 p.m. Quaid, Shane Johnson. An unknown ›››› A Nous la Liberte ’31 Comedy. Alpha Dog ›› ’06 Crime Drama. Bruce Au Pair II › Scheming heirs plot to wreck The Beautician and the Beast ›› ’97 motorist pursues three friends after a bar fight. Raymond Cordy, Henri Marchand. An Willis, Emile Hirsch. A teenage drug dealer a billionaire’s romance. ‘G’ (2:00) (FAMILY) Comedy. Fran Drescher, Timothy (2:00) (KOCB-34) Sat. 2 a.m. escaped con turns industrial in this technological kidnaps a junkie’s younger brother. (2:00) (USA) Sat. 8 a.m. Dalton. A Jewish hairdresser gives a foreign Black Irish A teen struggles to rise above his satire. (2:00) (TCM) Sun. 1:15 a.m. Wed. 1 a.m. August › The Internet company of two brothers despot a new attitude. (2:00) (KOCB-34) Sun. family’s dysfunction. (R) (1:34) (SHOW) Thu. The Abandoned Horrifying events await a The Amateurs Small-town citizens make an lurches toward disaster. (R) (1:28) (SHOW) 1 p.m. (WGN-A) Tue. 7 p.m. 2:45 p.m. woman at her family’s former home. (1:45) (IFC) amateur porn film. -

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 007 A View to A Kill DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Diamonds are Forever DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Dr. No BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 For Your Eyes Only BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 007 From Russia with Love BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2002 007 James Bond: Licence to Kill DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Living Daylights DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Pierce Brosnan Collection DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 2 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Sean Connery Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 Live and Let Die BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 Moonraker BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 5/16/2000 007 The Man with The Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Man with the Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Spy Who Loved Me DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Thunderball BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 12/19/2001 007 You Only Live Twice BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 10 Secrets for Success and Inner Peace DVD DYE Not Rated 12/2/2011 3/24/2009 Thursday, June 17, 2021 Page 1 of 231 Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 10 Things I Hate About You (10th Ann DVD Edition) DVD TEN PG-13