Using Geographic Information Systems to Organize and Coordinate Holistic Watershed Resource Management John M.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

The Cacapon Settlement: 1749-1800 31

THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 5 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 The existence of a settlement of Brethren families in the Cacapon River Valley of eastern Hampshire County in present day West Virginia has been unknown and uninvestigated until the present time. That a congregation of Brethren existed there in colonial times cannot now be denied, for sufficient evidence has been accumulated to reveal its presence at least by the 1760s and perhaps earlier. Because at this early date, Brethren churches and ministers did not keep records, details of this church cannot be recovered. At most, contemporary researchers can attempt to identify the families which have the highest probability of being of Brethren affiliation. Even this is difficult due to lack of time and resources. The research program for many of these families is incomplete, and this chapter is offered tentatively as a basis for additional research. Some attempted identifications will likely be incorrect. As work went forward on the Brethren settlements in the western and southern parts of old Hampshire County, it became clear that many families in the South Branch, Beaver Run and Pine churches had relatives who had lived in the Cacapon River Valley. Numerous families had moved from that valley to the western part of the county, and intermarriages were also evident. Land records revealed a large number of family names which were common on the South Branch, Patterson Creek, Beaver Run and Mill Creek areas. In many instances, the names appeared first on the Cacapon and later in the western part of the county. -

Upper Kanawha Watershed Main Report

Total Maximum Daily Loads for Selected Streams in the Upper Kanawha Watershed, West Virginia FINAL REPORT January 2005 Final Upper Kanawha Watershed TMDL Report CONTENTS Executive summary...................................................................................................................... ix 1. Report Format....................................................................................................................1 2. Introduction........................................................................................................................1 2.1 Total Maximum Daily Loads...................................................................................1 2.2 Water Quality Standards..........................................................................................4 3. Watershed Description and Data Inventory....................................................................5 3.1 Watershed Description.............................................................................................5 3.2 Data Inventory.........................................................................................................7 3.3 Impaired Waterbodies..............................................................................................7 4. Metals and pH Source Assessment.................................................................................13 4.1 Metals and pH Point Sources.................................................................................14 4.1.1 Mining Point Sources.................................................................................14 -

Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report

~ ~ U. S. Army Corps Interstate Commission of Engineers on the Potomac River Basin Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report APRIL 2020 Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District Laura Felter and Julia Fritz and Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin Cherie Schultz, Claire Buchanan, and Gordon Michael Selckmann Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Study Authority ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Congressional Authorizations and Project Objectives .................................................................. 3 1.4 Study Area Management .............................................................................................................. 4 2 Scoping Studies ..................................................................................................................................... 7 3 Watershed Conditions Analysis ........................................................................................................... -

Butler County Natural Heritage Inventory, 1991

BUTLER COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY Lisa L. Smith, Natural Heritage Ecologist Charles W. Bier, Associate Director, Natural Science and Stewardship Department Paul G. Wiegman, Director, Natural Science and Stewardship Department Chris J. Boget, Data Manager Bernice K. Beck, Data Handler Western Pennsylvania Conservancy 316 Fourth Avenue Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222 July 1991 BUTLER COUNTY NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 4 COUNTY OVERVIEW 9 PENNSYLVANIA NATURAL DIVERSITY INVENTORY 14 NATURAL HERITAGE INVENTORY METHODS 15 RESULTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 133 LITERATURE CITED 134 APPENDICES I. Federal and State Endangered Species Categories, Global and State Element Ranks 135 II. County Significance Ranks 141 III. Potential Natural Heritage Inventory Form 142 IV. Recommended Natural Heritage Field Survey Form 143 V. Classification of Natural Communities in Pennsylvania (Draft) 144 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Summary of sites in order of relative county significance 20 2. Important managed areas protecting biotic resources in Butler County 24 3. Butler County municipality summaries 27 Tables summarizing USGS quadrangles Baden 116 Barkeyville 37 Butler 103 Chicora 93 Curtisville 125 East Butler 90 Eau Claire 41 Emlenton 44 Evans City 108 Freeport 128 Grove City 34 Harlansburg 75 Hilliards 51 Mars 119 Mount Chestnut 86 Parker 48 Portersville 77 Prospect 81 Saxonburg 100 Slippery Rock 63 Valencia 122 West Sunbury 57 Worthington 97 Zelienople 113 LIST OF FIGURES PAGE 1. USGS quadrangle map index of Butler County 25 2. Municipalities of Butler County 26 3 INTRODUCTION Butler County possesses a wealth of natural resources including its flora, fauna, and natural habitats such as forests, wetlands, and streams. -

Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004

WEST VIRGINIA Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004 West Virginia Division of Natural Resources D I Investment in a Legacy --------------------------- S West Virginia’s anglers enjoy a rich sportfishing legacy and conservation ethic that is maintained T through their commitment to our state’s fishery resources. Recognizing this commitment, the R Division of Natural Resources endeavors to provide a variety of quality fishing opportunities to meet I increasing demands, while also conserving and protecting the state’s valuable aquatic resources. One way that DNR fulfills this part of its mission is through its fish hatchery programs. Many anglers are C aware of the successful trout stocking program and the seven coldwater hatcheries that support this T important fishery in West Virginia. The warmwater hatchery program, although a little less well known, is still very significant to West Virginia anglers. O West Virginia’s warmwater hatchery program has been instrumental in providing fishing opportunities F to anglers for more than 60 years. For most of that time, the Palestine State Fish Hatchery was the state’s primary facility dedicated to the production of warmwater fish. Millions of walleye, muskellunge, channel catfish, hybrid striped bass, saugeye, tiger musky, and largemouth F and smallmouth bass have been raised over the years at Palestine and stocked into streams, rivers, and lakes across the state. I A recent addition to the DNR’s warmwater hatchery program is the Apple Grove State Fish Hatchery in Mason County. Construction of the C hatchery was completed in 2003. It was a joint project of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the DNR as part of a mitigation agreement E for the modernization of the Robert C. -

Gazetteer of West Virginia

Bulletin No. 233 Series F, Geography, 41 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOU A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA I-IEISTRY G-AN3STETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 A» cl O a 3. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OP THE INTEKIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. C. , March 9, 190Jh SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of West Virginia! Very respectfully, HENRY GANNETT, Geogwvpher. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 3 A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA. HENRY GANNETT. DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. The State of West Virginia was cut off from Virginia during the civil war and was admitted to the Union on June 19, 1863. As orig inally constituted it consisted of 48 counties; subsequently, in 1866, it was enlarged by the addition -of two counties, Berkeley and Jeffer son, which were also detached from Virginia. The boundaries of the State are in the highest degree irregular. Starting at Potomac River at Harpers Ferry,' the line follows the south bank of the Potomac to the Fairfax Stone, which was set to mark the headwaters of the North Branch of Potomac River; from this stone the line runs due north to Mason and Dixon's line, i. e., the southern boundary of Pennsylvania; thence it follows this line west to the southwest corner of that State, in approximate latitude 39° 43i' and longitude 80° 31', and from that corner north along the western boundary of Pennsylvania until the line intersects Ohio River; from this point the boundary runs southwest down the Ohio, on the northwestern bank, to the mouth of Big Sandy River. -

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Q One ...........................1st week of March Twice a month .............. February-April CR Varies ...........................................Varies BW One ........................................... January M One each month ........... February-May One .................................................. May W Two..........................................February MJ One each month ............January-April One ........................................... January One each week ....................March-May Y One ................................................. April BA One each week ...................................... X After April 1 or area is open to public One ...............................................March F weeks of October 19 and 26 Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Anawalt – McDowell M Laurel – Mingo MJ Anderson – Kanawha BA Lick Creek – Wayne MJ Baker – Ohio Q Little Beaver – Raleigh MJ Barboursville – Cabell BA Logan County Airport – Logan Q Bear Rock Lakes – Ohio BW Mason Lake – Monongalia M Berwind – McDowell M Middle Wheeling Creek – Ohio BW Big Run – Marion Y Miletree – Roane BA Boley – Fayette M Mill Creek – Barbour M Brandywine – Pendleton BW-F Millers Fork – Wayne Q Brushy Fork – Pendleton BW Mountwood – Wood MJ Buffalo Fork – Pocahontas BW-F Newburg – Preston M Cacapon – Morgan W-F New Creek Dam 14 – Grant BW-F Castleman Run – Brooke, Ohio BW Pendleton – Tucker -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

Buffalo Creek Watershed Conservation Plan 10-Year

BUFFALO CREEK WATERSHED CONSERVATION PLAN 10-YEAR UPDATE September 2019 Buffalo Creek Watershed Conservation Plan 10- Year Update Armstrong, Butler, and Allegheny Counties, Pennsylvania Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania (ASWP) This project was funded in part by a grant from the Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds. Prepared with support from GAI Consultants, Inc. Buffalo Creek Watershed Conservation Plan 10-Year Update | 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ASWP is grateful for the support it received while conducting the 10-year update to the Buffalo Creek Watershed Conservation Plan as well as during the development of the original plan. Thank you to the Buffalo Creek Watershed community members for providing input and support during the planning process. ASWP would like to recognize Dave Beale for his commitment to conservation in the watershed. We are deeply grateful for his support during this plan update and in awe of all that he has been able to accomplish for the watershed. ASWP would like to thank the following people for participating in stakeholder interviews: Dave Beale, Forester, Surveyor, and Armstrong Conservancy Charles Bier, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Conservation Science Anthony Beers, PAFB Watershed Conservation Officer Mark Caruso, Freeport Middle School Anne Daymut, Western Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation Tye Desiderio, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Jeff Fliss, PA DEP Southwest Office Will Kmetz, Boy Scout Leader Virginia Lindsay, Landowner Ron Lybrook, PA DEP Northwest Office Bob -

Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication was made possible by the support of the following organizations and individuals: Center for Excellence in Disabilities at West Virginia University, Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center West Virginia Assistive Technology System (WVATS) West Virginia Division of Natural Resources West Virginia Division of Tourism Partnerships in Assistive Technologies, Inc. (PATHS) Special thanks to Stephen K. Hardesty and Brittany Valdez for their enthusiasm while working on this Guide. 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 3 • How to Use This Guide ......................................... 4 • ADA Sites .............................................................. 5 • Types of Fish ......................................................... 7 • Traveling in West Virginia ...................................... 15 COUNTY INDEX .......................................................... 19 ACTIVITY LISTS • Public Access Sites ............................................... 43 • Lakes ..................................................................... 53 • Trout Fishing ......................................................... 61 • River Float Trips .................................................... 69 SITE INDEX ................................................................. 75 SITE DESCRIPTIONS .................................................. 83 APPENDICES A. Recreation Organizations ......................................207 B. Trout Stocking Schedule .......................................209 -

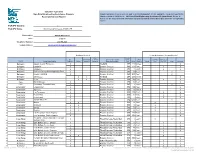

2013 Non-Point Engineering Assistance Program Annual Reporting Is Required on a Calendar Year Basis February 1

Calendar Year 2013 Non-Point Engineering Assistance Program Annual reporting is required on a calendar year basis February 1. Please upload the completed report to the Accomplishments Report Attachments tab in eLINK for the 2013 Non-Point Engineering Assistance Program Grant . Please be sure to use the instructions and information categories provided at the red triangles above the corresponding column. TSA/JPO Number: 8 TSA/JPO Name North Central Minnesota SWCD JPB Prepared by: William Westerberg Date: 01/09/14 Telephone Number: 218-755-4341 E-mail Address: [email protected] Assistance Provided Technical Assistance Funding Source(s) Other Primary Site Construction Technical Type of Practice Assisted Practice Unit of Clean Water State other SWCD Project Identification Evaluation Design Assistance Assistance (From List Provided) Code Unit(s) Measure Federal Fund than CWF Local Landowner 1 Beltrami Agassiz 4(John Erickson) x Wetland 657 180 acres x 2 Beltrami Chadwick x Erosion Control 580 135 feet x x 3 Beltrami Chadwick x Erosion Control 378 1 each x x 4 Beltrami Beltrami County-Mississippi High Bank x Erosion Control 580 60 feet x 5 Beltrami Buzzle Township x Erosion Control 560 475 feet x 6 Beltrami Stelter LLC x x Wetland 657 235 acres x 7 Beltrami Heim x x Erosion Control 580 140 feet x x 8 Cass Humrickhouse x Erosion Control 580 50 feet x 9 Cass Shingabee Township Road x Erosion Control 587 1 each x 10 Clearwater Engebretson x Erosion Control 580 100 feet x 11 Clearwater Johnson x Erosion Control 350 35 acres x 12