That Turbine Blades Be Feathered Or Stopped at Iowa Wind Speeds in Order to Minimize the Number of Bat Fatalities As Much Possibie, If Fkible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Form Location Owner Of

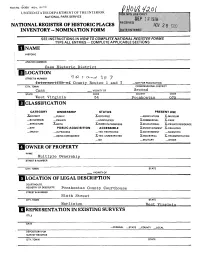

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTOCOMPLETE NATIONAL REG/STEP FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON Cass Historic District LOCATION STREETS. NUMBER County Routes 1 and 7 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN Cass VICINITY OF STATE CODE CODE West Virginia 54 075 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .XDISTRICT _PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL X-PARK —STRUCTURE X.BOTH X_WORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE X-ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED XlNDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple Ownership STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE _ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Pocahontas County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Ninth Street CITY. TOWN STATE Marlinton West Virginia. TiTLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _ UNEXPOSED The first men who worked for the lumber company on Leatherbark Run in Pocahontas County were housed in all sorts of crude shelters. It is quite probable that those construction workers built their own pole lean-tos, brush shelters, or some type of dug-outs. Before Cass was incorporated and named in 1902, it could be that the men with families who came early to work for the company built small rough-lumber cottages off company property. -

The Cacapon Settlement: 1749-1800 31

THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 5 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 The existence of a settlement of Brethren families in the Cacapon River Valley of eastern Hampshire County in present day West Virginia has been unknown and uninvestigated until the present time. That a congregation of Brethren existed there in colonial times cannot now be denied, for sufficient evidence has been accumulated to reveal its presence at least by the 1760s and perhaps earlier. Because at this early date, Brethren churches and ministers did not keep records, details of this church cannot be recovered. At most, contemporary researchers can attempt to identify the families which have the highest probability of being of Brethren affiliation. Even this is difficult due to lack of time and resources. The research program for many of these families is incomplete, and this chapter is offered tentatively as a basis for additional research. Some attempted identifications will likely be incorrect. As work went forward on the Brethren settlements in the western and southern parts of old Hampshire County, it became clear that many families in the South Branch, Beaver Run and Pine churches had relatives who had lived in the Cacapon River Valley. Numerous families had moved from that valley to the western part of the county, and intermarriages were also evident. Land records revealed a large number of family names which were common on the South Branch, Patterson Creek, Beaver Run and Mill Creek areas. In many instances, the names appeared first on the Cacapon and later in the western part of the county. -

A Retrospective Tiered Environmental Assessment of the Mount Storm Wind Energy Facility, West Virginia, Usa

- ORNL/TM-2012/515 A RETROSPECTIVE TIERED ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MOUNT STORM WIND ENERGY FACILITY, WEST VIRGINIA, USA November 26, 2012 Rebecca A. Efroymson and Robin J. Day Oak Ridge National Laboratory M. Dale Strickland Western EcoSystems Technology DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY Reports produced after January 1, 1996, are generally available free via the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Information Bridge. Web site http://www.osti.gov/bridge Reports produced before January 1, 1996, may be purchased by members of the public from the following source. National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Telephone 703-605-6000 (1-800-553-6847) TDD 703-487-4639 Fax 703-605-6900 E-mail [email protected] Web site http://www.ntis.gov/support/ordernowabout.htm Reports are available to DOE employees, DOE contractors, Energy Technology Data Exchange (ETDE) representatives, and International Nuclear Information System (INIS) representatives from the following source. Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831 Telephone 865-576-8401 Fax 865-576-5728 E-mail [email protected] Web site http://www.osti.gov/contact.html This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. -

New Creek Wind Project 2018 Post-Construction Monitoring

New Creek Wind Project 2018 Post-construction Monitoring Results of April – November 2018 Curtailment Evaluation, Acoustic Bat Monitoring, and Bird and Bat Carcass Surveys January 31, 2019 Prepared for: New Creek Wind, LLC Prepared by: Stantec Consulting Services Inc. 30 Park Drive Topsham, ME 04086 NEW CREEK WIND PROJECT 2018 POST-CONSTRUCTION MONITORING Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ I 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 MONITORING OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................... 3 2.0 METHODS ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 TURBINE OPERATION AND CURTAILMENT EVALUATION ........................................ 3 2.2 ACOUSTIC MONITORING ............................................................................................. 4 2.2.1 Acoustic Detector Deployment ....................................................................... 4 2.2.2 Acoustic Data Analysis and Summary ............................................................ 5 2.3 BAT ACTIVITY AND TURBINE OPERATION ................................................................. 6 2.4 STANDARDIZED CARCASS -

Monongahela National Forest

Monongahela National Forest United States Department of Final Agriculture Environmental Impact Statement Forest Service September for 2006 Forest Plan Revision The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its program and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202)720- 2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202)720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal Opportunity provider and employer. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Monongahela National Forest Forest Plan Revision September, 2006 Barbour, Grant, Greebrier, Nicholas, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Preston, Randolph, Tucker, and Webster Counties in West Virginia Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 Responsible Official: Randy Moore, Regional Forester Eastern Region USDA Forest Service 626 East Wisconsin Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53203 (414) 297-3600 For Further Information, Contact: Clyde Thompson, Forest Supervisor Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 i Abstract In July 2005, the Forest Service released for public review and comment a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) that described four alternatives for managing the Monongahela National Forest. Alternative 2 was the Preferred Alternative in the DEIS and was the foundation for the Proposed Revised Forest Plan. -

Download 2013 Accomplishments

Prepared by CASRI – www.restoreredspruce.org TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2013 Highlighted Projects .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Volunteers Lead the Way in Red Spruce Restoration at Canaan Valley NWR ...................................... 4 Maintaining Momentum on the Mower Tract: Moving from Barton Bench to Lambert .................. 5 Thunderstruck: A Major Conservation Win for TNC and CASRI ................................................................ 7 Researchers in the Trees: Getting Spruced Up .................................................................................................. 8 CASRI Accomplishments, 2013 ................................................................................................................................... 10 GOAL 1. MAINTAIN AND INCREASE OVERALL AREA OF ECOLOGICALLY FUNCTIONING RED SPRUCE COMMUNITIES WITHIN THEIR HISTORIC RANGE. ..................................................................... 10 GOAL II. INCREASE THE BIOLOGICAL INTEGRITY OF EXISTING RED SPRUCE NORTHERN- HARDWOOD COMMUNITIES................................................................................................................................... 15 GOAL III. PROTECT HABITAT FOR KEY WILDLIFE SPECIES AND COMMUNITIES -

Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report

~ ~ U. S. Army Corps Interstate Commission of Engineers on the Potomac River Basin Planning Assistance to States Jennings Randolph Lake Scoping Study Phase II Report APRIL 2020 Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District Laura Felter and Julia Fritz and Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin Cherie Schultz, Claire Buchanan, and Gordon Michael Selckmann Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Study Authority ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Congressional Authorizations and Project Objectives .................................................................. 3 1.4 Study Area Management .............................................................................................................. 4 2 Scoping Studies ..................................................................................................................................... 7 3 Watershed Conditions Analysis ........................................................................................................... -

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

DIVISION of NATURAL RESOURCES ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 Earl Ray Tomblin Governor, State of West Virginia

Natural Resources DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES ANNUAL REPORT 2011-2012 Earl Ray Tomblin Governor, State of West Virginia Keith Burdette Secretary, Department of Commerce Frank Jezioro Director, Division of Natural Resources Emily J. Fleming Assistant to the Director / Legislative Liaison Bryan M. Hoffman Executive Secretary, Administration Section 324 4th Avenue South Charleston, West Virginia 25303 David E. Murphy Chief, Law Enforcement Section Telephone: 304-558-2754 Fax: 304-558-2768 Kenneth K. Caplinger Chief, Parks and Recreation Section Web sites: www.wvdnr.gov Curtis I. Taylor www.wvstateparks.com Chief, Wildlife Resources Section www.wvhunt.com www.wvfish.com Joe T. Scarberry www.wonderfulwv.com Supervisor, Land and Streams Electronic mail: Natural Resources Commissioners [email protected] Jeffrey S. Bowers, Sugar Grove [email protected] Byron K. Chambers, Romney [email protected] David M. Milne, Bruceton Mills [email protected] Peter L. Cuffaro, Wheeling David F. Truban, Morgantown Kenneth R. Wilson, Chapmanville Thomas O. Dotson, White Sulphur Springs The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources Annual Report 2011-2012 is published by the Division of Natural Resources and the Department of Commerce Communications. It is the policy of the Division of Natural Resources to provide its facilities, services, programs and employment opportunities to all persons without regard to sex, race, age, religion, national origin or ancestry, disability, or other protected group status. Foreword LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Foreword i -

Science and Nature in the Blue Ridge Region

7-STATE MOUNTAIN TRAVEL GUIDE hether altered, restored or un- touched by humanity, the story of the Blue Ridge region told by nature and science is singularly inspiring. Let’s listen as she tells Wus her past, present and future. ELKINS-RANDOLPH COUNTY TOURISM CVB ) West Virginia New River Gorge Let’s begin our journey on the continent’s oldest river, surrounded by 1,000-foot cliffs. Carving its way through all the geographic provinces in the Appalachian Mountains, this 53-mile-long north-flowing river is flanked by rocky outcrops and sandstone cliffs. Immerse your senses in the sights, sounds, fragrances and power of the Science and inNature the Blue Ridge Region flow at Sandstone Falls. View the gorge “from the sky” with a catwalk stroll 876 feet up on the western hemisphere’s longest steel arch bridge. C’mon along as we explore the southern Appalachians in search of ginormous geology and geography, nps.gov/neri fascinating flora and fauna. ABOVE: See a bird’s-eye view from the bridge By ANGELA MINOR spanning West Virginia’s New River Gorge. LEFT: Learn ecosystem restoration at Mower Tract. MAIN IMAGE: View 90° razorback ridges at Seneca Rocks. ABOVE: Bluets along the trail are a welcome to springtime. LEFT: Nequi dolorumquis debis dolut ea pres il estrum et Um eicil iume ea dolupta nonectaquo conecus, ulpa pre 34 BLUERIDGECOUNTRY.COM JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2021 35 ELKINS-RANDOLPH COUNTY TOURISM CVB Mower Tract acres and hosts seven Wilderness areas. MUCH MORE TO SEE IN VIRGINIA… Within the Monongahela National fs.usda.gov/mnf ) Natural Chimneys Park and Camp- locale that includes 10 miles of trails, Forest, visit the site of ongoing high- ground, Mt. -

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River North Fork Watershed Project/Friends of Blackwater MAY 2009 This report was made possible by a generous donation from the MARPAT Foundation. DRAFT 2 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 TABLE OF Figures ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 THE UPPER NORTH BRANCH POTOMAC RIVER WATERSHED ................................................................................... 7 PART I ‐ General Information about the North Branch Potomac Watershed ........................................................... 8 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Geography and Geology of the Watershed Area ................................................................................................. 9 Demographics .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Land Use ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025.