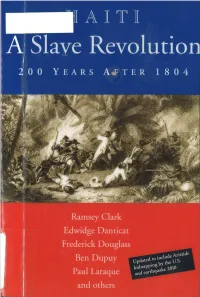

Haiti: a Slave Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLR James and the Black Jacobins

Atlantic Studies Global Currents ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjas20 Unsilencing the Haitian Revolution: C. L. R. James and The Black Jacobins Rachel Douglas To cite this article: Rachel Douglas (2020): Unsilencing the Haitian Revolution: C. L. R. James and TheBlackJacobins , Atlantic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14788810.2020.1839283 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2020.1839283 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 19 Nov 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjas20 ATLANTIC STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2020.1839283 Unsilencing the Haitian Revolution: C. L. R. James and The Black Jacobins Rachel Douglas French and Comparative Literature, School of Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Glasgow, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Exploring the genesis, transformation and afterlives of The Black Rewriting; Haitian Jacobins, this article follows the revision trail of James’s evolving Revolution; Toussaint interest in Toussaint Louverture. How does James “show” as Louverture; Caribbean; drama versus “tell” as history? Building on Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s theatre/drama; history from below idea of “silencing the past,” this article argues that James engages in an equally active and transitive reverse process of unsilencing the past. James’s own unsilencing of certain negative representations of the Haitian Revolution is evaluated, as is James’s move away from presenting the colonized as passive objects, instead turning them instead into active subjects. -

Soup Joumou Webinar and Partake in the Layout Editor Feast of Knowledge That It Turned out to Be

L’OUVERTURE A QU AR T E R L Y P U B L I C AT I O N | DR . J E A N - CL A UD E D U T È S , E D I TOR | V OL 2 NO 1 O F F I C E R S A FEW WORDS FROM OUR EDITOR Mr. Michelet (Mike) Moïse Hello and welcome back! 2020 has seamlessly merged into CHAIRPERSON 2021, bringing with it the chaos, confusion, and helplessness that COVID-19 and its mismanagement have brought to this Dr. Jean-Claude Dutès country. A silver lining, a ray of hope may have been sighted in the VICE-CHAIRPERSON horizon, however. Elections were held and there has been a transition Dr. Guylaine L. Richard to an administration that offers a more sanguine, disciplined, and SECRETARY competent approach to the management of this pandemic. We hope that it will be able to translate its aspirations into Mr. Frantz Y. Richard reality for the sake of the country and our own. We wish the TREASURER Biden-Harris administration much luck and persistent courage in its effort, likely to be Herculean, to redress the national vessel Ms. Cosy Clergé Joseph towards less tumultuous waters. To paraphrase poet Amanda Gorman, with intense fervor, we DIRECTOR OF INTERNAL COMMUNICATIONS hope to march forward to what shall be, and not what was. Ms. Jocelyne Cameau At our other home, the situation is no less dire. Some, however, would contend that it is far worse, DIRECTOR OF EXTERNAL with a future smeared by uncertainty and no silver lining on the horizon. -

The Children of San Souci, Dessalines/Toussaint, and Pétion

The Children of San Souci, Dessalines/Toussaint, and Pétion by Paul C. Mocombe [email protected] West Virginia State University The Mocombeian Foundation, Inc. Abstract This work, using a structurationist, structural Marxist understanding of consciousness constitution, i.e., phenomenological structuralism, explores the origins of the contemporary Haitian oppositional protest cry, “the children of Pétion v. the children of Dessalines.” Although viewed within racial terms in regards to the ideological position of Pétion representing the neoliberal views of the mulatto elites, and economic reform and social justice representing the ideological position of Dessalines as articulated by the African masses, this article suggests that the metaphors, contemporarily, have come to represent Marxist categories for class struggle on the island of Haiti within the capitalist world-system under American hegemony at the expense of the African majority, i.e., the Children of Sans Souci. Keywords: African-Americanization, Vodou Ethic and the Spirit of Communism, Religiosity, Black Diaspora, Dialectical, Anti-dialectical, Phenomenological Structuralism Introduction Since 1986 with the topple of the Haitian dictator, Jean-Claude “Baby-Doc” Duvalier (1951-2014), whose family ruled Haiti for almost thirty-years, the rallying cry of Haitian protest movements against dictatorship and American neoliberal policies on the island has been, “the children of Dessalines are fighting or stand against the children of Pétion.” The politically charged moniker is an allusion to the continuous struggles over control of the Haitian nation- state and its ideological apparatuses between the Africans who are deemed the descendants of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the father of the Haitian nation-state; and the mulatto elites (and more recently the Syrian class) who are deemed heirs of the mulatto first President of the Haitian Republic, Alexandre Pétion. -

Contested Symbolism in the Flags of New World Slave Risings

Contested Symbolism in the Flags of New World Slave Risings Steven A. Knowlton Throughout the summer of 1800, an enslaved blacksmith of Richmond, Virginia, named Gabriel conspired with fellow bondspeople to rise in arms and fight for their freedom. Among his plans was a scheme to paint a flag with the phrase “Death or Liberty” to be carried at the head of the column that would march into the city.1 Gabriel’s slogan inverted the words of his fellow Virginian Patrick Henry, whose famous oration on the eve of the American Revolution concluded, “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”2 It is a well-known irony of history that among those who fought for American independence from British rule—and couched their rhetoric in terms of “freedom” and “liberty”—were some of the largest slaveholders on the continent, including Henry.3 In popular memory, their struggle against King George III has been valorized, but so have the efforts of those who sought emancipation for slaves. For example, historical markers now stand at key locations in Gabriel’s career, and the Richmond History Center has made an artist’s conception of Gabriel’s image one of fifty key objects that define the city’s story.4 (Figure 1) As Gabriel’s adaptation of Henry’s rhetoric demonstrates, opposing parties are known to assign conflicting meanings to shared symbols; flags are among the most prominent of these, as documented throughout vexillological literature.5 Slaves who engaged in violent conflict with their masters often used flags mod- eled on those of their oppressors. -

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy A Journey Through Time A Resource Guide for Teachers HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center @ Brooklyn College 2900 Bedford Avenue James Hall, Room 3103J Brooklyn, NY 11210 Copyright © 2005 Teachers and educators, please feel free to make copies as needed to use with your students in class. Please contact HABETAC at 718-951-4668 to obtain copies of this publication. Funded by the New York State Education Department Acknowledgments Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy: A Journey Through Time is for teachers of grades K through 12. The idea of this book was initiated by the Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center (HABETAC) at City College under the direction of Myriam C. Augustin, the former director of HABETAC. This is the realization of the following team of committed, knowledgeable, and creative writers, researchers, activity developers, artists, and editors: Marie José Bernard, Resource Specialist, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Menes Dejoie, School Psychologist, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Yves Raymond, Bilingual Coordinator, Erasmus Hall High School for Science and Math, Brooklyn, NY Marie Lily Cerat, Writing Specialist, P.S. 181, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Christine Etienne, Bilingual Staff Developer, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Amidor Almonord, Bilingual Teacher, P.S. 189, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Peter Kondrat, Educational Consultant and Freelance Writer, Brooklyn, NY Alix Ambroise, Jr., Social Studies Teacher, P.S. 138, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Professor Jean Y. Plaisir, Assistant Professor, Department of Childhood Education, City College of New York, New York, NY Claudette Laurent, Administrative Assistant, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Christian Lemoine, Graphic Artist, HLH Panoramic, New York, NY. -

The Pearl of the Antilles: a Serial History of Haiti 2

THE PEARL OF THE ANTILLES: A SERIAL HISTORY OF HAITI PART II INSURRECTION TO INDEPENDENCE Michael S. VanHook International Strategic Alliances The Pearl of the Antilles: A Serial History of Haiti 2 THE PEARL OF THE ANTILLES: A SERIAL HISTORY OF HAITI Michael S. VanHook, International Strategic Alliances Copyright © 2019 by Michael S. VanHook All rights reserved. This resource is provided to give context and essential background information for those persons with an interest in serving the people of Haiti. It is made available without charge by the publisher, ISA Publishing Group, a division of International Strategic Alliances, Inc. Scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing is permitted. If you would like to use material from this book, please contact the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support. ISA Publishing Group A division of International Strategic Alliances, Inc. P.O. Box 691 West Chester, OH 45071 For more information about the work of International Strategic Alliances, contact us at [email protected]. For more information about the author or for speaking engagements, contact him at [email protected]. The Pearl of the Antilles: A Serial History of Haiti 3 THE PEARL OF THE ANTILLES: A SERIAL HISTORY OF HAITI Michael S. VanHook, International Strategic Alliances INTRODUCTION 4 PART II: INSURRECTION TO INDEPENDENCE 7 1. BOIS CAÏMAN CEREMONY 8 2. REVOLUTION 12 3. “THE OPENER OF THE WAY” 18 4. NAPOLEON VS. TOUSSAINT 24 5. INDEPENDENCE -

A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution Viewpoints/Puntos De Vista: Themes and Interpretations in Latin American History

A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution Viewpoints/Puntos de Vista: Themes and Interpretations in Latin American History Series editor: J ü rgen Buchenau The books in this series will introduce students to the most signifi cant themes and topics in Latin American history. They represent a novel approach to designing supplementary texts for this growing market. Intended as supplementary textbooks, the books will also discuss the ways in which historians have interpreted these themes and topics, thus demonstrating to students that our understanding of our past is con- stantly changing, through the emergence of new sources, methodologies, and historical theories. Unlike monographs, the books in this series will be broad in scope and written in a style accessible to undergraduates. Published A History of the Cuban Revolution Aviva Chomsky Bartolom é de las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas Lawrence A. Clayton Beyond Borders: A History of Mexican Migration to the United States Timothy J. Henderson The Last Caudillo: Alvaro Obreg ó n and the Mexican Revolution J ü rgen Buchenau A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution Jeremy D. Popkin In preparation Creoles vs. Peninsulars in Colonial Spanish America Mark Burkholder Dictatorship in South America Jerry Davila Mexico Since 1940: The Unscripted Revolution Stephen E. Lewis A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution Jeremy D. Popkin A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2012 2012 Jeremy D. Popkin Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. -

Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5

The School Board of Broward County, Florida Benjamin J. Williams, Chair Beverly A. Gallagher, Vice Chair Carole L. Andrews Robin Bartleman Darla L. Carter Maureen S. Dinnen Stephanie Arma Kraft, Esq. Robert D. Parks, Ed.D. Marty Rubinstein Dr. Frank Till Superintendent of Schools The School Board of Broward County, Florida, prohibits any policy or procedure which results in discrimination on the basis of age, color, disability, gender, national origin, marital status, race, religion or sexual orientation. Individuals who wish to file a discrimination and/or harassment complaint may call the Director of Equal Educational Opportunities at (754) 321-2150 or Teletype Machine TTY (754) 321-2158. Individuals with disabilities requesting accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may call Equal Educational Opportunities (EEO) at (754) 321-2150 or Teletype Machine TTY (754) 321-2158. www.browardschools.com Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5 Dr. Earlean C. Smiley Deputy Superintendent Curriculum and Instruction/Student Support Sayra Velez Hughes Executive Director Multicultural & ESOL Program Services Education Elizabeth L. Watts, Ph.D. Multicultural Curriculum Development/Training Specialist Multicultural Department Broward County Public Schools ACKNOWLEDGMENT Our sincere appreciation is given to Mrs. Margaret M. Armand, Bilingual Education Consultant, for granting us permission to use her Haitian oil painting by Francoise Jean entitled, "Children Playing with Kites” for the cover of the Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5. She has also been kind enough to grant us permission to use artwork from her private collection which have been made into slides for this guide. TABLE OF CONTENTS Writing Team................................................................................................................................. i Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

Trinidad and Tobago) and U.S.A

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2010 Women and Resistance in the African Diaspora, with Special Focus on the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago) and U.S.A. Clare Johnson Washington Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Washington, Clare Johnson, "Women and Resistance in the African Diaspora, with Special Focus on the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago) and U.S.A." (2010). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 137. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.137 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Women and Resistance in the African Diaspora, with Special Focus on the Caribbean (Trinidad and Tobago) and U.S.A. by Clare Johnson Washington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Interdisciplinary Studies Thesis Committee: E. Kofi Agorsah, Chair Primus St. John Rita Pemberton Portland State University ©2010 ABSTRACT American history has celebrated the involvement of black women in the “underground railroad,” but little is said about women’s everyday resistance to the institutional constraints and abuses of slavery. Many Americans have probably heard of and know about Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth – two very prominent black female resistance leaders and abolitionists-- but this thesis addresses the lives of some of the less-celebrated and lesser-known (more obscure) women; part of the focus is on the common tasks, relationships, burdens, and leadership roles of these very brave enslaved women. -

Celebrating Haitian Heritage Booklet

School District of Palm Beach County, Florida Department of Multicultural Education Department of Public Affairs CELEBRATING HAITIAN HERITAGE A Teacher’s Resource Guide Palm Beach County Florida Prepared by Bito David, Public Affairs Specialist Department of Multicultural Education - Department of Public Affairs [email protected] April 2005 The School District of Palm Beach County, Florida Mission Statement The School Board of Palm Beach County is committed to excellence in education and preparation of all our students with the knowledge, skills and ethics required for responsible citizenship and productive employment. School Board Members Tom Lynch, Chairman William Graham, Vice Chairman Monroe Benaim, MD Paulette Burdick Mark Hansen Dr. Sandra Richmond Debra Robinson, MD Superintendent Arthur C. Johnson, Ph.D. Chief Academic Officer Ann Killets Chief Officer of Administration Gerald Williams Assistant Superintendent, Curriculum and Learning Support Wayne Gent Executive Director Chief Public Information Officer Multicultural Education Department Public Affairs Department Margarita P. Pinkos, Ed.D. Nat Harrington ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS HAITIAN HERITAGE COMMITTEE MEMBERS Bito David, Public Affairs Specialist, Department of Public Affairs Jacques Eric Toussaint, Translator/Interpreter Department of Multicultural Education Roody Barthèlemy, Translator/Interpreter, Department of Multicultural Education Bernadette Guirand Léger, Executive Director, Joseph Laurore Foundation Roger Pierre, President, Bel’Art Promotions Florence Elie, Community -

Haitians: a People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 416 263 UD 032 123 AUTHOR Bernard, Marie Jose; Damas, Christine; Dejoie, Menes; Duval, Joubert; Duval, Micheline; Fouche, Marie; Marcellus, Marie Jose; Paul, Cauvin TITLE Haitians: A People on the Move. Haitian Cultural Heritage Resource Guide. INSTITUTION New York City Board of Education, Brooklyn, NY. Office of Bilingual Education. ISBN ISBN-1-55839-416-8 PUB DATE 1996-00-00 NOTE 176p. AVAILABLE FROM Office of Instructional Publications, 131 Livingston Street, Brooklyn, NY 11201. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Awareness; Cultural Background; Diversity (Student); Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Haitian Creole; *Haitians; History; *Immigrants; Inservice Teacher Education; *Multicultural Education; Resource Materials; Teaching Guides; Teaching Methods; Urban Schools; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS Haiti; New York City Board of Education ABSTRACT This cultural heritage resource guide has been prepared as a tool for teachers to help them understand the cultural heritage of their Haitian students, their families, and their communities in order to serve them better. Although Haiti became an independent country in 1804, the struggle of its people for justice and freedom has never ended. Many Haitians have left Haiti for political, social, and economic reasons, and many have come to the larger cities of the United States, particularly New York City. This guide contains the following sections: (1) "Introduction"; (2) "Haiti at a Glance"; (3) "In Search of a Better Life";(4) "Haitian History"; (5) "Haitian Culture"; (6) "Images of Haiti"; and (7)"Bibliography," a 23-item list of works for further reading. (SLD) ******************************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Tnalr Or Conrenrs (C) Copyright 2004, 2010 ISBN 978-0 -97 47 S2t-4-3 Prefaces International Action Center 2004: Why This Book 55 W

Haiti: A Slave Revolution 200 years after 1 804 Tnalr Or ConrENrs (c) Copyright 2004, 2010 ISBN 978-0 -97 47 s2t-4-3 Prefaces International Action Center 2004: Why This Book 55 W. 17th St., 5th Floor, NewYork, NY 10011 2010: Why a Revised Edition vlll Phone: 212 633-6646 rA e,'r, Timeline IX Website: www.iacenter.org tit,'n!,,,ts. Dedication xlll E-mail : iacenter org !, 1Q" @iacenter. ., A,.,,t,0 L l/ | Haiti's Agonies and Exaltations Ramsey Clark I as widely as possible. We want to make the ideas in this book available Photo Bssay on Haiti selected by Pat Chin t7 Any properly attributed selection or part of a chapter within "fair-use" guidelines may be used without permission. Part l- Haiti in History 35 "The Only Way," "Exile Is Stale Bread" and "Reign of a Human Race" O Paul ThankYou Dessalines Fdlix Moniseau-Leroy JI Laraque and used here with author's permission. "Thank You Dessalines" O F6lix Moniseau-Leroy and used here with permission Haiti Needs Reparations, Not Sanctions Pat Chin 4l ofthe author's estate. Haiti's Impact on U.S.-what "voodoo economics" "No Greater Shame" @ Edwidge Danticat and used here with author's permission. & high school textbooks reveal Greg Dunkel 45 "The Longest Day" O Stan Goff and used here with author's permission. Cuba, Haiti and John Brown-to rebel is justified Opinions expressed by contributors to this book represent their personal views Sara Flounders 59 and are not necessarily those of the Intemational Action Center. Lecture on Haiti Frederick Douglass 65 Cover design: Katherine Kean.