Considerations Regarding the Morlachs Migrations from Dalmatia to Istria and the Venetian Settlement Policy During the 16Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Sense of Memory

Copyright © Museum Tusculanums Press Making Sense of Memory Monuments and Landscape in Croatian Istria1 Jonas Frykman Frykman, Jonas 2003: Making Sense of Memory. Monuments and Landscape in Croatian Istria. – Ethnologia Europaea 33:2: 107–120. When the actual terror is over, how do you reconcile without trying to pay back? With the falling apart of Yugoslavia, past, suppressed injustices remerged and were frequently used to connect the present with bitter memories. In the ethnically diverse region of Istria, however, it has been difficult for any group to claim its interpretation of history to be superior to others. Seeking to explain the Istrian case and within it the role of the esuli, the article juxtaposes the material discourse represented by monuments with the workings of memory and the dynamics which jostle sleeping, hidden, or private memory into public discourse. It is argued that in Istria, the absence of an ethnic “master narrative,” and the coexistence of many different groups sharing the territory has been useful for keeping nightmarish memory of ethnic violence at bay. Instead, place has come to matter more than history. Within landscapes and monuments, experiences of terror and narratives of martyrdom find a resting place, however uneasy. Prof. Dr. Jonas Frykman, Dept. of Ethnology, University of Lund, Finngatan 8, SE-223 62 Lund. E-mail: [email protected] “Say a hawk came out of the blue and seized one Memory is not really what people recollect, of your chickens. What can you do? You can’t get but how they manage to make sense of the past. -

When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans ᇺᇺᇺ

when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans when ethnicity did not matter in the balkans ᇺᇺᇺ A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods john v. a. fine, jr. the university of michigan press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2006 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2009 2008 2007 2006 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fine, John V. A. (John Van Antwerp), 1939– When ethnicity did not matter in the Balkans : a study of identity in pre-nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the medieval and early-modern periods / John V.A. Fine. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-472-11414-6 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-472-11414-x (cloth : alk. paper) 1. National characteristics, Croatian. 2. Ethnicity—Croatia. 3. Croatia—History—To 1102. 4. Croatia—History—1102–1527. 5. Croatia—History—1527–1918. I. Title. dr1523.5.f56 2005 305.8'0094972–dc22 2005050557 For their love and support for all my endeavors, including this book in your hands, this book is dedicated to my wonderful family: to my wife, Gena, and my two sons, Alexander (Sasha) and Paul. -

Vina Croatia

Wines of CROATIA unique and exciting Croatia as a AUSTRIA modern country HUNGARY SLOVENIA CROATIA Croatia, having been eager to experience immediate changes, success and recognition, has, at the beginning of a new decade, totally altered its approach to life and business. A strong desire to earn quick money as well as rapid trade expansion have been replaced by more moderate, longer-term investment projects in the areas of viticulture, rural tourism, family hotels, fisheries, olive growing, ecological agriculture and superior restaurants. BOSNIA & The strong first impression of international brands has been replaced by turning to traditional HERZEGOVINA products, having their origins in a deep historic heritage. The expansion of fast-food chains was brought to a halt in the mid-1990’s as multinational companies understood that investment would not be returned as quickly as had been planned. More ambitious restaurants transformed into centres of hedonism, whereas small, thematic ones offering several fresh and well-prepared dishes are visited every day. Tradition and a return to nature are now popular ITALY Viticulture has been fully developed. Having superior technology at their disposal, a new generation of well-educated winemakers show firm personal convictions and aims with clear goals. The rapid growth of international wine varietals has been hindered while local varietals that were almost on the verge of extinction, have gradually gained in importance. Not only have the most prominent European regions shared their experience, but the world’s renowned wine experts have offered their consulting services. Biodynamic movement has been very brisk with every wine region bursting with life. -

Istria to Veneto: a Culinary Route

Istria to Veneto: A Culinary Route 9 Days Istria to Veneto: A Culinary Route Food lovers, raise your taste buds to the next level on this culinary and cultural journey that traces Croatia's Istrian Peninsula, Slovenia's Julian Alps, and Italy's Friuli-Venezia- Giulia region. Take in the best sites in this trio of countries, experiencing rich historical sites and spectacular national parks on moderate hikes. Go wine tasting, learn how to hunt truffles, taste olive oil, and sample regional delicacies in the Mediterranean as you've never seen it before, far from the crowds. Luxurious hotels awaiting at the end of each day make for a dreamy finale. Details Testimonials Arrive: Zagreb, Croatia "The trip was exceptional. We saw a part of the world we had never Depart: Venice, Italy experienced. The accommodations were wonderful and the food fantastic. Duration: 9 Days Perfection!" Robert B. Group Size: 4-16 Guests Minimum Age: 15 Years Old "Amazing trip of a lifetime! Would recommend to anyone who loves to hike, Activity Level: Level 2 eat, drink wine and enjoy a good laugh." . Tyler A. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 Easy to moderate walking tours Enjoy Tuscan-style landscapes and This custom designed MT Sobek take travelers through hard culinary specialties of Croatia's trip allows plenty of leisure time to find orchards, vineyards, up-and-coming gastronomical to swim in the Adriatic Sea and hillsides, and medieval villages region, Istria, with far less visit artisan shops and galleries. across 3 countries in 9 days. tourists than in neighboring Italy. -

Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in the Dalmatian Coast Through Greening Coastal Development - COAST’

UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME ‘Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in the Dalmatian Coast through Greening Coastal Development - COAST’ ATLAS ID – 43199; PIMS - 2439 Report of the Mid Term Evaluation Mission 6th May 2010 Nigel Varty (International Consultant) Ru !ica Maru "i# (National Consultant) Acknowledgements The Mid Term Evaluation (MTE) Team would like to thank all the COAST Project and UNDP staff, and the many other people interviewed who gave freely of their time and ideas (all those listed in Annex 4 contributed). We would especially like to thank the staff of the PIU and the UNDP Croatia CO for their excellent logistical skills and hospitality – particularly Mr. Gojko Berengi (National Project Manager) and Mr Ognjen !kunca (Deputy Project Manager), and Jelena Kurtovi " (UNDP Croatia) for their organizational efforts and patience with the requests of the MTE. Following completion of the Draft Report on 8th April 2009, review comments were received from the PIU, UNDP CO and Regional Coordination Unit in Bratislava, and the Ministry of Environment Protection, Physical Planning and Construction. Comments have either been included in the text where these related to factual inaccuracies in the draft, or have been reproduced in full as a footnote to the appropriate text. The MTET has commented on these in some cases. We thank each of the reviewers for providing useful and constructive feedback, which helped to strengthen the final version of this report. The MTET has tried to provide a fair and balanced assessment of the Project’s achievements and performance to date and to provide constructive criticism. We have made recommendations aimed at helping to improve project delivery and sustainability and replication of project results for the remainder of the Project, as well as to aid in the development and execution of future GEF projects. -

GENS VLACHORUM in HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs)

ПЕТАР Б. БОГУНОВИЋ УДК 94(497.11) Нови Сад Оригиналан научни рад Република Србија Примљен: 21.01.2018 Одобрен: 23.02.2018 Страна: 577-600 GENS VLACHORUM IN HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs) Part 1 Summary: This article deals with the issue of the term Vlach, that is, its genesis, dis- persion through history and geographical distribution. Also, the article tries to throw a little more light on this notion, through a multidisciplinary view on the part of the population that has been named Vlachs in the past or present. The goal is to create an image of what they really are, and what they have never been, through a specific chronological historical overview of data related to the Vlachs. Thus, it allows the reader to understand, through the facts presented here, the misconceptions that are related to this term in the historiographic literature. Key words: Vlachs, Morlachs, Serbs, Slavs, Wallachia, Moldavia, Romanian Orthodox Church The terms »Vlach«1, or later, »Morlach«2, does not represent the nationality, that is, they have never represented it throughout the history, because both of this terms exclusively refer to the members of Serbian nation, in the Serbian ethnic area. –––––––––––– [email protected] 1 Serbian (Cyrillic script): влах. »Now in answer to all these frivolous assertions, it is sufficient to observe, that our Morlacchi are called Vlassi, that is, noble or potent, for the same reason that the body of the nation is called Slavi, which means glorious; that the word Vlah has nothing -

Territorialisation and De-Territorialisation of the Borderlands Communities in the Multicultural Environment: Morlachia and Little Wallachia

Acta geographica Bosniae et Herzegovinae 2014, 2, 45-53 Original scientific papaer __________________________________________________________________________________ TERRITORIALISATION AND DE-TERRITORIALISATION OF THE BORDERLANDS COMMUNITIES IN THE MULTICULTURAL ENVIRONMENT: MORLACHIA AND LITTLE WALLACHIA Borna Fuerst-Bjeliš University of Zagreb Faculty of Science, Department of Geography Marulićev trg 19, 10 000 Zagreb, Croatia [email protected] The area of research refers to the Croatian - Bosnian and Herzegovinian borderlands, the contact area of three different imperial traditions in the Early Modern period; Ottoman, Habsburg and Venetian. That was the meeting place of East and West, Christianity and Islam and maritime and continental traditions. Frequent border changes were followed by migrations and introduction of new (other) social and cultural communities. The Border- land represents an area of multiple contacts and a multicultural environment. Historical maps reveal the process of territorialisation and de-territorialisation of the Borderland communities, as well as the process of construction and deconstruction of spatial (regional) concepts. Spatial concepts of Morlachia and Little Wallachia, constructed under the distinct social-political conditions of the threefold border, were dissolved by the change in these conditions. Key words: Borderlands, Early Modern period, Morlachia, Little Wallachia, Croatia, Bosnia- Herzegovina, regional identity, history of cartography INTRODUCTION: THE SPATIAL-TEMPORAL CONTEXT The Early Modern period in the history of Croatia and its neighbouring countries was burdened by frequent changes in the borders between three great imperial systems, and by diverse religious and cultural traditions. During three centuries - the 16th to the 19th – that was a territory defined by the border areas of the Habsburg Monarchy, the Ottoman Empire and the Venetian Republic. -

Istria & Dalmatia

SPECIAL OFFER - SAVE £200 PER PERSON ISTRIA & DALMATIA A summer voyage discovering the beauty of Istria & Kvarner Bay aboard the Princess Eleganza 28th May to 6th June, 6th to 15th June*, 15th to 24th June, 24th June to 3rd July* 2022 Mali Losinj Brijuni Islands National Park Vineyard in the Momjan region oin us for a nine night exploration of the beautiful Istrian coast combined with a visit to the region’s bucolic interior and some charming islands. Croatia’s Istrian coast and Momjan J Opatija Kvarner Bay offers some of the world’s most beautiful coastal scenery, picturesque islands Porec Motovun Rovinj and a wonderfully tranquil and peaceful atmosphere. The 36-passenger Princess Eleganza CROATIA is the perfect vessel for our journey allowing us to moor centrally in towns and call into Pula secluded bays, enabling us to fully discover all the region has to offer visiting some Brijuni Rab Islands marvellous places which do not cater for the big ships along the way. Each night we will Mali Losinj remain moored in the picturesque harbours affording the opportunity to dine ashore on some evenings and to enjoy the floodlit splendour and lively café society which is so atmospheric. Zadar Our island calls will include Rab with its picturesque Old Town, Losinj Island with its striking bays Dugi Otok which is often to referred to as Croatia’s best-kept secret, Dugi Otok where we visit a traditional fishing village and the islands of the Brijuni which comprise one of Croatia’s National Parks. Whilst in Pula, we will visit one of the best preserved Roman amphitheatres in the world and we will also spend a day travelling into the Istrian interior to explore this area of disarming beauty and visit the village of Motovun, in the middle of truffle territory, where we will sample the local gastronomy and enjoy the best views of the Istrian interior from the ramparts. -

Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland As Cultural Mediators

Chapter 10 Connectivity, Mobility, and Mediterranean “Portable Archaeology”: Pashas from the Dalmatian Hinterland as Cultural Mediators Gülru Necipoğlu Considering the mobility of persons and stones is one way to reflect upon how movable or portable seemingly stationary archaeological sites might be. Dalmatia, here viewed as a center of gravity between East and West, was cen- tral for the global vision of Ottoman imperial ambitions, which peaked during the 16th century. Constituting a fluid “border zone” caught between the fluctu- ating boundaries of three early modern empires—Ottoman, Venetian, and Austrian Habsburg—the Dalmatian coast of today’s Croatia and its hinterland occupied a vital position in the geopolitical imagination of the sultans. The Ottoman aspiration to reunite the fragmented former territories of the Roman Empire once again brought the eastern Adriatic littoral within the orbit of a tri-continental empire, comprising the interconnected arena of the Balkans, Crimea, Anatolia, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa. It is important to pay particular attention to how sites can “travel” through texts, drawings, prints, objects, travelogues, and oral descriptions. To that list should be added “traveling” stones (spolia) and the subjective medium of memory, with its transformative powers, as vehicles for the transmission of architectural knowledge and visual culture. I refer to the memories of travelers, merchants, architects, and ambassadors who crossed borders, as well as to Ottoman pashas originating from Dalmatia and its hinterland, with their extraordinary mobility within the promotion system of a vast eastern Mediterranean empire. To these pashas, circulating from one provincial post to another was a prerequisite for eventually rising to the highest ranks of vizier and grand vizier at the Imperial Council in the capital Istanbul, also called Ḳosṭanṭiniyye (Constantinople). -

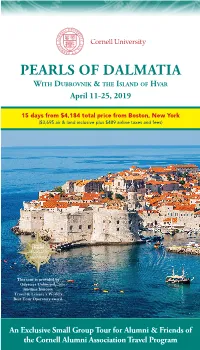

Pearls of Dalmatia with Dubrovnik & the Island of Hvar

PEARLS OF DALMATIA WITH DUBROVNIK & THE ISLAND OF HVAR April 11-25, 2019 15 days from $4,184 total price from Boston, New York ($3,695 air & land inclusive plus $489 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni & Friends of the Cornell Alumni Association Travel Program Dear Alumni, Parents, and Friends, We invite you to be among the thousands of Cornell alumni, parents and friends who view the Cornell Alumni Association (CAA) Travel Program as their first choice for memorable travel adventures. If you’ve traveled with CAA before, you know to expect excellent travel experiences in some of the world’s most interesting places. If our travel offerings are new to you, you’ll want to take a closer look at our upcoming tours. Working closely with some of the world’s most highly-respected travel companies, CAA trips are not only well organized, safe, and a great value, they are filled with remarkable people. This year, as we have for more than forty years, are offering itineraries in the United States and around the globe. Whether you’re ascending a sand dune by camel, strolling the cobbled streets of a ‘medieval town’, hiking a trail on a remote mountain pass, or lounging poolside on one of our luxury cruises, we guarantee ‘an extraordinary journey in great company.’ And that’s the reason so many Cornellians return, year after year, to travel with the Cornell Alumni Association. -

The Croatian Ustasha Regime and Its Policies Towards

THE IDEOLOGY OF NATION AND RACE: THE CROATIAN USTASHA REGIME AND ITS POLICIES TOWARD MINORITIES IN THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA, 1941-1945. NEVENKO BARTULIN A thesis submitted in fulfilment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales November 2006 1 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Nicholas Doumanis, lecturer in the School of History at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney, Australia, for the valuable guidance, advice and suggestions that he has provided me in the course of the writing of this thesis. Thanks also go to his colleague, and my co-supervisor, Günther Minnerup, as well as to Dr. Milan Vojkovi, who also read this thesis. I further owe a great deal of gratitude to the rest of the academic and administrative staff of the School of History at UNSW, and especially to my fellow research students, in particular, Matthew Fitzpatrick, Susie Protschky and Sally Cove, for all their help, support and companionship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Department of History at the University of Zagreb (Sveuilište u Zagrebu), particularly prof. dr. sc. Ivo Goldstein, and to the staff of the Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv) and the National and University Library (Nacionalna i sveuilišna knjižnica) in Zagreb, for the assistance they provided me during my research trip to Croatia in 2004. I must also thank the University of Zagreb’s Office for International Relations (Ured za meunarodnu suradnju) for the accommodation made available to me during my research trip. -

Civil Society Monitoring on the Implementation of the National Roma Integration Strategy and Decade Action Plan in CROATIA

Civil Society Monitoring on the Implementation of the National Roma Integration Strategy and Decade Action Plan in CROATIA in 2012 and 2013 DECADE OF ROMA INCLUSION 2005-2015 Civil Society Monitoring on the Implementation of the National Roma Integration Strategy and Decade Action Plan in CROATIA in 2012 and 2013 Prepared by a civil society coalition comprising the following organizations Institute of the Association for Transitional Researches and National Education – STINA (lead organisation) Roma National Council n Centre for Peace, Legal Advice and Psychosocial Assistance Written by Ljubomir Mikić n Milena Babić Coordinated by the Decade of Roma Inclusion Secretariat Foundation in cooperation with the Making the Most of EU Funds for Roma Program of the Open Society Foundations DECADE OF ROMA INCLUSION 2005-2015 www.romadecade.org DECADE OF ROMA INCLUSION 2005-2015 2 Published by Decade of Roma Inclusion Secretariat Foundation Teréz körút 46. 1066 Budapest, Hungary www.romadecade.org Design and layout: www.foszer-design.com Proofreading: Christopher Ryan ©2014 by Decade of Roma Inclusion Secretariat Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any forms or by any means without the permission of the Publisher. ISSN: 2064-8413 All civil society monitoring reports are available at www.romadecade.org/civilsocietymonitoring Civil SocietyCivil Monitoring This report was prepared by a civil society coalition comprising the following organisations: Institute of the 3 Association for Transitional Researches and National Education – STINA Institute (lead organization), Roma National Council, and Centre for Peace, Legal Advice and Psychosocial Assistance. The lead researcher of croatia the coalition is Ljubomir Mikić (Centre for Peace, Legal Advice and Psychosocial Assistance) and the project manager is Stojan Obradović (STINA Institute).