Clarence Irving and the Rediscovery of Black America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis 042813

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library THE CREATION OF THE DOUBLEDAY MYTH by Matthew David Schoss A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah August 2013 Copyright © Matthew David Schoss 2013 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Matthew David Schoss has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Larry Gerlach , Chair 05/02/13 Date Approved Matthew Basso , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved Paul Reeve , Member 05/02/13 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Donna M. White, Interim Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In 1908, a Special Base Ball Commission determined that baseball was invented by Abner Doubleday in 1839. The Commission, established to resolve a long-standing debate regarding the origins of baseball, relied on evidence provided by James Sullivan, a secretary working at Spalding Sporting Goods, owned by former player Albert Spalding. Sullivan solicited information from former players and fans, edited the information, and presented it to the Commission. One person’s allegation stood out above the rest; Abner Graves claimed that Abner Doubleday “invented” baseball sometime around 1839 in Cooperstown, New York. It was not true; baseball did not have an “inventor” and if it did, it was not Doubleday, who was at West Point during the time in question. -

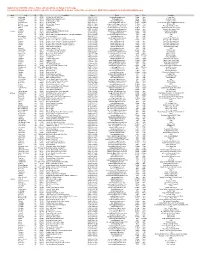

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Lagrange College Baseball and Statistics Travel Seminar Draft Itinerary: May 17-26, 2020

LaGrange College Baseball and Statistics Travel Seminar Draft Itinerary: May 17-26, 2020 Day 1 Sunday, May 17, 2020 Depart Atlanta for Philadelphia Sample Flight Delta Flight DL 1494 Depart Atlanta (ATL) at 8:56 AM Arrive Philadelphia (PHL) at 10:59 AM 10:59 Arrive Philadelphia, 11:30 Meet Guide and Transfer to the Hotel 1:00 Group Lunch 2:30 - 4:30 Founding Fathers Tour of Philadelphia Experience the history of the United States on this guided, 2-hour, small-group walking tour around Philadelphia, the birthplace of freedom in America. See Independence Hall, where the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence (this tour does not enter Independence Hall). Snap a selfie with the iconic Liberty Bell. Learn about Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn, and see where George Washington, the first President of the United States, lived. Then check out the galleries and eateries in Old City Philadelphia, America's most historic square mile 6:30 Group Welcome Dinner Day 2 Monday, May 18, 2020 Breakfast served in hotel 9:00 - 12:00 Cultural Experience Philadelphia Museum of Art 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, PA 19130 Run up the Rocky Steps in front of the museum and take a picture with the Rocky Statue, then enter one of the largest and most renowned museums in the country. Find beauty, enchantment, and the unexpected among artistic and architectural achievements from the United States, Asia, Europe, and Latin America. 12:30 - 1:30 Group Lunch Philadelphia Cheesesteak Lunch Pat's King of Steaks or Geno's Steaks 2:00 - 3:30 Meeting or Cultural Activity Philadelphia Phillies 4:00 - 5:30 Citizens Bank Park Tour One Citizens Bank Way Philadelphia, PA 19148 Tour guests will be treated to a brief audio/visual presentation of Citizens Bank Park, followed by an up-close look at the ballpark. -

Mediaguide.Pdf

American Legion Baseball would like to thank the following: 2017 ALWS schedule THURSDAY – AUGUST 10 Game 1 – 9:30am – Northeast vs. Great Lakes Game 2 – 1:00pm – Central Plains vs. Western Game 3 – 4:30pm – Mid-South vs. Northwest Game 4 – 8:00pm – Southeast vs. Mid-Atlantic Off day – none FRIDAY – AUGUST 11 Game 5 – 4:00pm – Great Lakes vs. Central Plains Game 6 – 7:30pm – Western vs. Northeastern Off day – Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Mid-South, Northwest SATURDAY – AUGUST 12 Game 7 – 11:30am – Mid-Atlantic vs. Mid-South Game 8 – 3:30pm – Northwest vs. Southeast The American Legion Game 9 – Northeast vs. Central Plains Off day – Great Lakes, Western Code of Sportsmanship SUNDAY – AUGUST 13 Game 10 – Noon – Great Lakes vs. Western I will keep the rules Game 11 – 3:30pm – Mid-Atlantic vs. Northwest Keep faith with my teammates Game 12 – 7:30pm – Southeast vs. Mid-South Keep my temper Off day – Northeast, Central Plains Keep myself fit Keep a stout heart in defeat MONDAY – AUGUST 14 Game 13 – 3:00pm – STARS winner vs. STRIPES runner-up Keep my pride under in victory Game 14 – 7:00pm – STRIPLES winner vs. STARS runner-up Keep a sound soul, a clean mind And a healthy body. TUESDAY – AUGUST 14 – CHAMPIONSHIP TUESDAY Game 15 – 7:00pm – winner game 13 vs. winner game 14 ALWS matches Stars and Stripes On the cover Top left: Logan Vidrine pitches Texarkana AR into the finals The 2017 American Legion World Series will salute the Stars of the ALWS championship with a three-hit performance and Stripes when playing its 91st World Series (92nd year) against previously unbeaten Rockport IN. -

1943 Sacramento Solons ©Diamondsinthedusk.Com

TEAM SNAPSHOT: 1943 Sacramento Solons ©DiamondsintheDusk.com 1943 Sacramento Solons (41-114) “From Riches to Rags” Hitting Pos. G AB R H 2B 3B HR RBI SB AVG After winning the 1942 Pacific Coast League Nippy Jones 2B 129 477 44 145 25 6 4 37 9 .304 crown on the final day of the season, the Mickey Burnett SS 145 552 57 152 21 4 6 43 32 .275 Sacramento Solons fall to last place in 1943, Fred Hensley 3B 133 434 35 119 20 5 1 44 0 .274 Pete Petersen C 98 278 24 75 14 6 5 34 3 .270 finishing 41-114 (.265) and 69 games behind Mickey Kavanaugh OF 141 485 34 129 23 2 1 40 16 .266 champion Los Angeles and 29 games behind Eddie Malone C 117 359 28 94 18 4 1 28 5 .262 the seventh-place Padres of San Diego. Manny Vias OF 108 346 38 84 13 3 0 24 6 .243 Bill Ramsey OF 110 379 44 89 14 2 0 21 28 .235 Jack Angle 1B 148 512 50 115 16 5 3 48 14 .225 Sacramento’s winning Dick Cole SS 26 76 3 17 0 1 0 0 0 .224 percentage of .265 is the Joe Molina OF 75 211 12 47 5 0 1 12 1 .223 worst in Pacific Coast Jake Suytar 1B 56 168 9 37 3 1 0 10 0 .220 League history. George Jumonville 3B 75 241 20 50 8 0 3 27 3 .207 Dan Phalen 1B 3 6 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 .167 Ken Penner P 3 1 - 1 0 0 0 0 0 1.000 The team’s best pitcher, Bud Byerly P 46 109 5 30 6 0 0 5 0 .275 left-hander Al Brazle, Jean-Pierre Roy P 27 59 3 15 1 0 0 3 0 .254 is 11-8 and leading the Al Brazle P 23 60 4 15 2 2 0 2 0 .250 PCL in ERA (1.69) when Paul Fitzke P 23 18 1 3 0 0 0 0 0 .167 Steve LeGault P 13 23 - 3 0 0 0 0 0 .130 the Cardinals call him Clyde Fischer P 14 8 - 1 0 0 0 0 0 .125 up on July 13, to replace James McFaden P 15 8 - 1 0 0 0 0 0 .125 pitcher Howie Pollet Clem Dreisewerd P 42 74 6 9 0 0 0 3 0 .122 who has entered the Al Brazle John Pintar P 42 68 2 6 0 0 0 2 0 .088 Army. -

Aa002686.Pdf (11.94Mb)

EJMERICAN LEGION NEWS SERVICE NATIONAL PUBLIC RELATIONS DIVISION—THE AMERICAN LEGION C. D. DeLoach, Chairman James C. Watkins, Director HEADQUARTERS P. O. Box 1055 1608 KSt., N. W. Indianapolis, Indiana 46206 Washington, D. C. 20006 (317) 635-8411 (202) 393-4811 AMERICAN LEGION NEWS BRIEFS FOR WEEK ENDING 8-6-76 "I join Legionnaires everywhere in extending deepest sympathy to the families of those comrades and sisters who were stricken following the Department Convention in Philadelphia." — American Legion National Commander Harry G. Wiles, in a state- ment regarding the mystery deaths of Pennsylvania Legionnaires. * * * At least 23 American Legionnaires who attended the Pennsylvania Department Convention in Philadelphia, Pa., July 21-24, have died from a painful and mysterious disease, and more than one hundred have been hospitalized throughout the state with similar symptoms to those which claimed the lives of other Legionnaires. * * * The American Legion National Commander Harry G. Wiles and the American Legion Auxiliary National President Lotys Schanel cancelled the scheduled visit to Phila- delphia for the Boys/Girls Nation Program due to the "unknown nature of the disease" which struck Pennsylvania Legionnaires. * * * Ted Williams, former Boston Red Sox outfielder who was hailed as one of base- ball's greatest hitters, will be the featured speaker at American Legion Baseball's World Series Banquet. The Banquet will be held in the Sheraton-Wayfarer Convention Center, Manchester, N.H., on Wednesday, Sept. 1, at 7 p.m., prior to the 1976 Ameri- can Legion World Series. * * * Representative Ray Roberts, chairman of the House Committee on Veterans Affairs, will be the featured Congressional speaker before The American Legion's Legislative and Veterans Affairs-Rehabilitation Commissions during meetings scheduled for the Legion's 58th National Convention in Seattle. -

Fact Sheet and History National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

FACT SHEET AND HISTORY NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME AND MUSEUM Baseball Beginnings 1905 The Mills Commission was established to determine the official origins of Baseball. 1908 The Mills Commission issued its final report, which stated that “the first scheme for playing baseball” was devised by Abner Doubleday at Cooperstown, NY in 1839. 1935 The “Doubleday baseball,” considered the first modern baseball, was discovered in a farmhouse near Cooperstown. With its stitched cover and cloth stuffing, the ball is a symbol of the legendary first baseball game of 1839 in Cooperstown, NY. Stephen C. Clark, a Cooperstown philanthropist, purchased the “Doubleday baseball” for $5 and created a one-room display of baseball objects in a local Cooperstown club that attracted wide attention. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1936 The Hall of Fame was established and the first players to be inducted included: Ty Cobb, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, Babe Ruth and Honus Wagner. Cobb earned the most votes. 1939 The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum opened in Cooperstown on June 12th, coinciding with Baseball’s centennial celebration. The Cooperstown Village Board of Trustees converted the pasture that was the legendary site of the original 1839 Doubleday ballgame to a full-fledged ballpark, named Doubleday field, which continues to be home to the annual Hall of Fame Game. By 1939, 25 players had been elected to the Hall of Fame; the 11 living Hall of Famers traveled to Cooperstown to celebrate Baseball’s centennial. The first commemorative Baseball stamp went on sale in the United States. -

Cooperstown: PAST PRESIDENT DR

REGISTRATION FORM 6TI1 ANNUAL CONFERENCE & EXHIBITION FEBRUARY 4-8, 1995 PIRATE CITY/McKECHNIE FIELD BRADENTON, FLORIDA FEES: !...::)(:, FULL CONFERENCE REGISTRATION: ::::...:.:::: This entitles me to admission to all educational seminars, the Welcome Reception, Awards Banquet, the trade show and four days of lunch and continental breakfast. Postmarked Postmarked Prior to 12/15/94 After 12/15/94 STMAMember $175 $200 Non-member $200 $225 Student $75 $100 (Island Theme Night & Seminar on Wheels is additional) OPTIONS (Check all that apply): THREE DAY EDUCATIONAL SESSIONS & EXHIBITS DAY: STMA Member $150 $175 Non-member $175 $200 Student $60 $85 !:.·:;:::.:}./ti ONE DAY OF EDUCATIONAL SESSIONS (Circle day): Sunday Monday Wednesday STMA Member $55 $65 Non-member $65 $75 Student $30 $40 SEMINAR ON WHEELS (BUS TOUR) (Feb. 4th, 9:00am - 5:00pm) $25 $30 ISLAND THEME NIGHT - DINNER (Feb. 5th, 7:00pm - 10:0Opm) $30 $35 ADDITIONAL AWARDS BANQUET TICKETS (Feb. 6th, 6:30pm - 10:0Opm) $35 $40 EXHIBITS ONLY BADGE (Feb., 7th McKechnie Field Tour & $25 $30 Exhibits Day 8:00am - 5:00pm) QUESTIONS: Call SmA headquarters at 312/644-6610 - ext 4731 FOR HOTEL RESERVATIONS: Please contact the Holiday Inn Riverfront at 813n47-3727. Please mention the SmA Conference to obtain our discounted rate of $89/single and $99/suite. RETURN WIlli PAYMENT TO: SmA, P.O. Box 809119, Chicago, IL 60680-9119 CHECKS PAYABLE TO: smA CREDIT CARD PAYMENT: Name on Credit Card Credit Card # Expiration Date ----- Circle Type of Credit Card: MASTER CARD VISA Circle 101 on Postage Free Card McKechnie Field Sports* Managers Association Make plans now to join your colleagues and the Sports Turf Managers Association (STMA) in the heart of baseball spring training country - Pirate City and McKechnie Field. -

The Newsletter of the Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club August 2018

The Newsletter of the Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club ________________________________________________________________________________ August 2018 The Fan Club held two more of its monthly pre-game Socials at SunTrust Park. The first was on Saturday, June 16th, in the Xfinity Cabanas before the game with the Padres. We moved to the nearby Xfinity Patio for the next Social on Wednesday, July 11th, before the Blue Jays game. It’s been fun meeting up with fellow Club members, talking Braves baseball (there’s a lot to talk about these days!), holding drawings for free Braves tickets, playing cornhole and foosball, and enjoying light refreshments. See our Social photo gallery at www.atl400.org/photo-gallery/gallery60/. th Our fifth and final Gameday Social of the season will take place on Thursday, August 16 , at 6:05, at the Xfinity Cabanas before our Braves take on the Rockies. If you haven’t been to one th of our Socials yet, come on out! Register by Monday, August 13 , at noon at www.atl400.org. The Tomahawk Times August 2018 Page 2 By Howard Evans, President Atlanta 400 Baseball Fan Club The Tomahawk Times audience is made up of passionate Braves fans. It is not breaking news to you that this season has been a joy ride journey as we head into the final six weeks of the season. Folks, we are pushing for a playoff slot and since the inception of the Wild Card, getting there over a long season is winning the battle. The Braves have endured their share of DL’s and remain the team to watch over a grueling upcoming schedule, in part due to earlier game postponements. -

Opponents Player Development Miscellaneous

FRONT OFFICE 2008 ATHLETICS REVIEW RECORDS HISTORY OPPONENTS PLAYER DEVELOPMENT MISCELLANEOUS ▲ OPPONENTS 311 Photos courtesy of the Cleveland Indians OPPONENTS 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS MEDIA GUIDE 2008 OAKLAND ATHLETICS Award Winner Award C.C. Sabathia 2007 American League Cy Young ▲ OPPONENTS Baltimore Orioles American League East Oriole Park at Camden Yards FRONT OFFICE 333 W. Camden Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Switchboard: (410) 685-9800 Press Box: (410) 547-6257 Media Relations: (410) 547-6150 Media Relations FAX: (410) 547-6272 Managing Partner. Peter Angelos Executive Vice President . John P. Angelos President, Baseball Operations . .Andy MacPhail 2008 ATHLETICS Dave Trembley Director, Media Relations. Bill Stetka (410) 547-6156 Record in Baltimore Director, Public Affairs . .Monica Pence (410) 547-6160 40-53 (1 season + interim) Traveling Secretary. Phil Itzoe (410) 547-6226 Career Record Stadium . Oriole Park at Camden Yards 40-53 (1 season + interim) Capacity / Opened . 48,190 / 1992 Orioles Hotel in Bay Area . .Parc 55 (San Francisco) (415) 392-8000 All-Time Series A’s Hotel in Baltimore. Renaissance Harborplace (410) 547-1200 All-Time Series Record REVIEW 958-913 2007 Series Recap At McAfee Coliseum 108-123 Date H-A W-L Score Winner Loser Date H-A W-L Score Winner Loser At Camden Yards 4/23 A W 6-5 D. Haren E. Bedard 7/20 H L 1-6 E. Bedard J. Blanton 4/24 A W 4-2 D. Braden J. Guthrie 7/21 H W 4-3 D. Haren S. Trachsel 47-36 5/25 A W 3-2 D. Haren E. Bedard 7/22 H L 0-2 J. -

2018-05-26 @ OAK Notes 051.Indd

PROBABLE PITCHERS ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS (26-24) at OAKLAND ATHLETICS (26-25) @ OAKLAND A'S Saturday, May 26, 2018 ♦ Oakland Coliseum ♦ Oakland, Calif. ♦ 1:05 p.m. AZT May 27 - 1:05 p.m. FSAZ/98.7 FM/KHOV 105.1 Fox Sports Arizona ♦ 98.7 FM Arizona's Sports Station ♦ Univision Deportes 105.1 FM RHP Zack Greinke (3-3, 3.71) vs. RHP Trevor Cahill (1-2, 2.75) Game No. 51 ♦ Road Game No. 25 ♦ Home Record: 14-12 ♦ Road Record: 12-12 VS. CINCINNATI REDS RHP Clay Buchholz (0-0, 1.80) vs. RHP Daniel Mengden (4-4, 3.30) May 28 - 1:10 p.m. FSAZ/620 AM/KHOV 105.1 TBA vs. Arizona Diamondbacks Communications 401 E. Jefferson Street, Phoenix, Ariz. 85004 602.462.6519 RHP Homer Bailey (1-6, 6.21) May 29 - 6:40 p.m. FSAZ/98.7 FM/KHOV 105.1 HERE’S THE STORY… TOUCHING ALL THE BASES TBA vs. ♦Arizona is making its fi rst trip to the Oakland Coliseum since RHP Luis Castillo (4-4, 5.34) July 1-3, 2011…the D-backs are 8-3 in their last 11 games @ A's MEMORIAL DAY ON MONDAY: The D-backs will honor those who May 30 - 12:40 p.m. FSAZ/620 AM/KHOV 105.1 since July 9, 2000. have sacrifi ced their lives serving our country throughout the TBA vs. game, including a moment of remembrance at 3 p.m. for all MLB RHP Sal Ramano (2-5, 5.62 + today) ♦Arizona is 3-1 this season in Interleague Play, having also taken teams…Players and coaches will wear a camoufl age-designed 2 of 3 from the Astros from May 4-6 @ Chase Field. -

The Bogus Boredom of Baseball

MAMBA, MLB, MINDSET THE BOGUS BOREDOM OF BASEBALL By Devin Blish “Baseball was, is, and always will be the best game in the world to me” is a quote from one of the most legendary baseball players ever, Babe Ruth. The majority of baseball players would, without a doubt, agree with Ruth. Those who do not play or know very little about baseball may think it’s a very boring, slow-paced game. In the summer of 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, Abner Doubleday invented the game of baseball, which eventually became America’s na- tional pastime. But today, most people would criticize the game, calling it “slow” and “boring.” Is it the two-to-three-hour games or the delay be- tween pitches? After much thought, I still refute these comments. Here’s why. PHOTO BY KYLE LLEWELLYN People that only played little league will usually say that they just sat Doubleday Field is a baseball field that is located in Coo- in the outfield and did nothing. But in reality, they didn’t want to play or perstown, NY two blocks away from the National Basball didn’t try. At the next level, such as travel ball or the high school team, the rules Hall of Fame. Every year from 1940 to 2008, a Hall of and excitement level change. The field gets bigger (from around 200-225 Fame Game was played there featuring two MLB teams. feet to around 400 feet) and the basepaths expand (from 60-90 feet). Not Spring Training ticket sales have seen an increase of up to 3.5 million only does the field change, but now you can lead off the bases and not attendees annually for both the American and National Leagues.