A Framework for Understanding Community-Based Environmental Stewardship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

York Road Community (SNAP)

Baltimore City’s York Road Community will be composed of vibrant urban neighborhoods. From its diverse blend of THE YORK ROAD COMMUNITY citizens to its unique shopping STRATEGIC NEIGHBORHOOD ACTION PLAN attractions, the Community will capture the essence and spirit of positive city living.FEBRUARY 2006 Acknowledgments Mayor’s Office of Neighborhoods Baltimore Housing Baltimore Development Corporation City of Baltimore Department of Transportation City of Baltimore Department of Recreation and Parks Baltimore City Police Department With special thanks to the members of the: York Road Partnership Steering Committee and Action Committees Neighborhood Organizations Govanstowne Business Association Martin O’Malley, Otis Rolley, III Mayor Director, Department of Planning City of Baltimore City of Baltimore Tamara Woods, Comprehensive Planner Kristin Smith, City Planner (2000- 2005) Eric Holcomb, Preservation Planner Adopted by the City of Baltimore Planning Commission February 2, 2006 Department of Planning Mission Statement To provide the highest level services and leadership in urban and strategic planning, historical and architectural preservation, zoning, design, development, and capital budgeting to promote the sustained economic, social, and community development of the City of Baltimore. Table of Contents What is SNAP? 1 Cluster Profile 2 Planning Process 3 History 3 Cluster Data 5 Housing and Neighborhood Revitalization 8 Recommendations 11 Accomplishments to Date 14 Commercial Revitalization 15 Recommendations 17 Accomplishments to -

All Hazards Plan for Baltimore City

All-Hazards Plan for Baltimore City: A Master Plan to Mitigate Natural Hazards Prepared for the City of Baltimore by the City of Baltimore Department of Planning Adopted by the Baltimore City Planning Commission April 20, 2006 v.3 Otis Rolley, III Mayor Martin Director O’Malley Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction .........................................................................................................1 Plan Contents....................................................................................................................1 About the City of Baltimore ...............................................................................................3 Chapter Two: Natural Hazards in Baltimore City .....................................................................5 Flood Hazard Profile .........................................................................................................7 Hurricane Hazard Profile.................................................................................................11 Severe Thunderstorm Hazard Profile..............................................................................14 Winter Storm Hazard Profile ...........................................................................................17 Extreme Heat Hazard Profile ..........................................................................................19 Drought Hazard Profile....................................................................................................20 Earthquake and Land Movement -

Nats Rushing Newsom to Mound Against Chisox

I Nats Rushing Newsom to Mound Against Chisox 4 Fifth in Row Battle of Undefeated ose or Triumph Ennis' Punch Tells for Phillies; Uline Gets Franchise Over Chicago Is Goal; Nines Bosox Maintain Lead By FRANCIS E. STANN Midget Tops Strong In Newly Formed Which Was the Best Batting Team? Hudson Foils Tribe Boys' Card Pro Court "If you were a pitcher,” asked one of the young Nats the other Loop Loop The two undefeated night, "would you rather pitch to the 1946 Red Sox or to some of those By Burton Hawkins teams In the Special Dispatch to Tha Star other like midget class of the Western Division great hitting teams, the Yankees of 1927, the Athletics of Double-O Bobo NEW Newsom, the air- of the Club of YORK, June 7.—Mike 1929 or the Yankees of 1937? I never saw any of these teams, Boys’ Washington except conditioned who was last owner the Red Sox we pia> today,” pitcher in Baseball League clash in the feature Uline, of Uline Arena in line of tomorrow’s Now there s posing a little question that could when modesty was being dis- five-game schedule. Washington, D. C., has purchased a stir a few It will be Eastern winners up arguments. If I were a pitcher I’d tributed, will establish a beachhead Quins, franchise in a new professional bas- to the Mexican of four straight, against Alexandria jump League, temporarily, any on Griffith Stadium’s ket mound to- B. undefeated in three ball league organized here yes- time these clubs came to town. -

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY and PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative

COVID-19 FOOD INSECURITY RESPONSE GROCERY AND PRODUCE BOX DISTRIBUTION SUMMARY April – June, 2020 Prepared by the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative OVERVIEW In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative developed an Emergency Food Strategy. An Emergency Food Planning team, comprised of City agencies and critical nonprofit partners, convened to guide the City’s food insecurity response. The strategy includes distributing meals, distributing food, increasing federal nutrition benefits, supporting community partners, and building local food system resilience. Since COVID-19 reached Baltimore, public-private partnerships have been mobilized; State funding has been leveraged; over 3.5 million meals have been provided to Baltimore youth, families, and older adults; and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot has launched. This document provides a summary of distribution of food boxes (grocery and produce boxes) from April to June, 2020, and reviews the next steps of the food distribution response. GOAL STATEMENT In response to COVID-19 and its impact on health, economic, and environmental disparities, the Baltimore Food Policy Initiative has grounded its short- and long-term strategies in the following goals: • Minimizing food insecurity due to job loss, decreased food access, and transportation gaps during the pandemic. • Creating a flexible grocery distribution system that can adapt to fluctuating numbers of cases, rates of infection, and specific demographics impacted by COVID-19 cases. • Building an equitable and resilient infrastructure to address the long-term consequences of the pandemic and its impact on food security and food justice. RISING FOOD INSECURITY DUE TO COVID-19 • FOOD INSECURITY: It is estimated that one in four city residents are experiencing food insecurity as a consequence of COVID-191. -

82 2011 Johns Hopkins Men's Lacrosse Guide

JHU’s All-Time NCAA Tournament Results Year Date Round Opponent JHU Seed/Opp. Seed Result Attendance City, State Stadium 2010 May 15 First Round #5 Duke -/5 L/5-18 1,813 Durham, NC Koskinen Stadium 2009 May 9 First Round #11 Brown 8/- (OT) W/12-11 12,142 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2009 May 17 Quarterfinals #5 Virginia 8/1 L/8-19 2,491 Annapolis, MD Navy Marine Corps Stadium 2008 May 11 First Round #16 Hofstra 5/- W/10-4 2,864 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2008 May 17 Quarterfinals #14 Navy 5/- W/10-4 17,017 Annapolis, MD Navy Marine Corps Stadium 2008 May 24 Semifinals #1 Duke 5/1 W/10-9 48,224 Foxboro, MA Gillette Stadium 2008 May 26 Championship #3 Syracuse 5/3 L/10-13 48,970 Foxboro, MA Gillette Stadium 2007 May 12 First Round #11 Notre Dame 3/- (OT) W/11-10 2,548 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2007 May 19 Quarterfinals #6 Georgetown 3/6 W/14-6 8,123 Princeton, NJ Princeton Stadium 2007 May 26 Semifinals #15 Delaware 3/- W/8-3 52,004 Baltimore, MD M&T Bank Stadium 2007 May 28 Championship #2 Duke 3/1 W/12-11 48,443 Baltimore, MD M&T Bank Stadium 2006 May 13 First Round #13 Penn 4/- W/13-3 1,964 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2006 May 20 Quarterfinals #5 Syracuse 4/5 L/12-13 8,335 Stony Brook, NY LaValle Stadium 2005 May 14 First Round Marist 1/- W/22-6 1,175 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2005 May 21 Quarterfinals #8 UMass 1/8 W/19-9 6,504 Baltimore, MD Homewood Field 2005 May 28 Semifinals #4 Virginia 1/4 (OT) W/9-8 45,275 Philadelphia, PA Lincoln Financial Field 2005 May 30 Championship #2 Duke 1/2 W/9-8 44,920 Philadelphia, PA Lincoln -

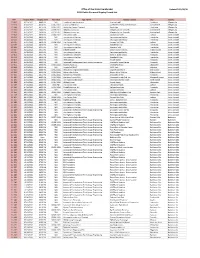

Office of the State Fire Marshal 2021 Public Firework Display Permit List

Office of the State Fire Marshal Updated 2021/09/30 2021 Public Firework Display Permit List 2021 Display Date Display Time Rain Date App. Name Display Location City County 21-004 03/19/2021 0800 PM N/A Frostburg State University Practive Field Frostburg Allegany Co 21-173 07/04/2021 0930 PM 07/05/2021 City of Cumberland Cumberland Parks and Recreation Cumberland Allegany Co 21-190 07/04/2021 0915 PM 07/05/2021 Rocky Gap Casion / Resport Rocky Gap Flintstone Allegany Co 21-143 07/18/2021 1000 PM 07/19/2021 Allegany County Fair Allegany Co Fair Grounds Cumberland Allegany Co 21-144 07/23/2021 1030 PM 07/24/2021 Allegany County Fair Allegany Co Fair Grounds Cumberland Allegany Co 21-003 02/03/2021 0830 PM 02/06/2021 The Cannon Club Cannon Golf Club Lothion Anne Arundel 21-023 04/10/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-024 04/28/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-035 05/07/2021 0830 PM 05/08/2021 The Cannon Club Cannon Golf Club Lothian Anne Arundel 21-049 05/20/2021 0830 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Weatherly Farm Friendship Anne Arundel 21-120 06/10/2021 0915 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Weavers Field Friendship Anne Arundel 21-117 06/12/2021 0915 PM N/A Stephen Bisbee Gibson Island Club Inc. Gibson Island Anne Arundel 21-025 06/18/2021 0930 PM N/A Herrington on the Bay Herrington on the Bay Friendship Anne Arundel 21-102 06/19/2021 0915 PM N/A Pyrotecnico Fireworks Wiley H. -

Neighborhood Statistical Area T G E N V H I a N E ST V I a E S Industrial Area T S

T H H A E T T F N O A O M A B O K L L G M N B K C O I C A R L K L R T X E S L E E A T E B R C A I N A H R E M S W L Y H W H L C Y T S O L A W K A O O L G A C G R W O N R O H T L O T N O E R L L A Z M D I E R N S E A W A O E N R I W O I C N A N R Y E N A G W L L R . E E Y V L E D R N N A D A H O E D N I O E N L A RD O A T E B S T E D V O A O E NAT V T A D L Y O R L R W R A H A S D A M H D E E V R W D Z R K A V A S N D A O LIMIT N A DR B E W A W L V V O R M E L L V P R I I E I O R D D A P E K E L E A O C K WILLOWGLEN S J N R E I I U L W D V K E I L G H R T W D O R V Y D P D L R L I E A L A N R P R H V V D M APPLEBY D R H A V N E A P I E H O E R E D D R R B N RD N N A E C A K D T D E A R U I E R D R N L V A N . -

Welcome to Baltimore This Is “Charm City”

Welcome To Baltimore This is “Charm City” If you have an interest, you’ll find it here. Baltimore features ... • Bustling downtown featuring the Inner Harbor with its many spots for shopping, dining and socializing. • Historic sites including the Edgar Allen Poe House, Babe Ruth House, first frigate of the U.S. Navy, U.S.F. Constellation and Fort McHenry. • Numerous museums and galleries, including the Baltimore Museum of Art (located adjacent to the Homewood Campus) and the Walters Art Gallery, which houses collections from early Egypt to the 19th century. • A full range of theater options featuring everything from Broadway, opera and dance to small repertory and avant-garde productions in such venues as Center Stage, the Hippodrome Theater, the Lyric Opera House and the Theater Project. • Two of the finest professional sports venues - Oriole Park at Camden The ESPN Zone (above) in Baltimore was the first of its kind Yards and M&T Bank Stadium. Major League Baseball’s Baltimore Ori- and is located downtown, within five miles of Johns Hopkins. oles play in arguably the finest baseball facility in the world, while the Ravens won the 2001 Super Bowl and have helped revitalize the city’s football-starved fans in a short pe- riod of time. • An ideal location. Baltimore is lo- cated within easy driving distance of the major metropolises of Wash- ington, DC, Philadelphia and New York. These cities, plus the many pleasures of the Chesapeake Bay, the rolling hills of Western Mary- land for camping, hiking and skiing, and the Atlantic beaches of Mary- land and Delaware are all within a few hours’ drive. -

Tuscany Canterbury

TUSCANY- Fall 2013 CANTERBURY NEIGHBORHOOD ASSOCIATION P.O. Box 26223 Baltimore, Maryland 21210 Presidents' Column TCNA ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP by Susan W. Talbott and A.J. O'Brien, TCNA Board Co-Presidents MEETING Good news—the roundabout, often Finally, current Traffic Committee Chair called the circle, was completed in early Jackie MacMillan and her excellent com- Tuesday, November 5 August, and many neighbors, including mittee have overseen the completion of the 7:00-9:30 p.m. Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke, attended roundabout. The full effect of this major Calvert Middle School auditorium a ribbon cutting on August 1st. This fall, change won't be known until schools open (Enter building from Tuscany Road; the City will plant daylillies in the two in the fall, but we all hope that the circle enter parking lot from Charles Street.) small planters in the splitter islands of the will slow traffic and make the roadway safer AGENDA roundabout so we'll have some pretty flow- for both pedestrians and cyclists. 1. Call to order ers in the late spring of 2014. The next big challenge for TCNA's 2. Opening remarks TCNA applauds the Department of Traffic Committee is the intersection at 3. Treasurer’s report Transportation (DOT) for completing University Parkway and 39th Street. The the construction in under one month. We committee is working in collaboration with 4. Committee reports especially appreciated the excellent work JHU and the community associations in 5. Old business done by the following people: Kohl Fallin Roland Park, Wyman Park, and Guilford in 6. New business (the DOT Northwest liaison), Jessica Lewis an effort to guide DOT as plans are made and Kevin Livingston (DOT engineers), to make this intersection safer. -

Market and Economic Analys League Lacrosse Stadium Green Branch

Market and Economic Analysis for a Proposed New Major League Lacrosse Stadium and Multi-Field Sports Complex at Green Branch Park in Prince George’s County, Maryland Prepared for: Presented by: Final Report December 2012 4427 W. Kennedy Boulevard ∙ Suite 200 ∙ Tampa, Florida 33609 ∙ Phone 813.281.1222 ∙ Fax 813.315.6040 www.crossroads-fl.com Crossroads Consulting Services is a Limited Liability Company December 21, 2012 Mr. Eric Johnson Maryland Stadium Authority 333 W. Camden St., Suite 500 Baltimore, MD 21201 Dear Mr. Johnson: Crossroads Consulting Services LLC (Crossroads Consulting) is pleased to present this market and economic analysis to the Maryland Stadium Authority (MSA) regarding a proposed new Major League Lacrosse (MLL) stadium and multi-field sports complex at Green Branch Park in Prince George’s County, Maryland (County). In accordance with our agreement, this report summarizes our research and analysis which is intended to assist the MSA and the County with their decisions regarding the potential development of the proposed new complex. The information contained in the report is based on estimates, assumptions, and information developed from market research, industry knowledge, input from potential demand generators, as well as other factors including data provided by the MSA, the County, and other secondary sources. We have utilized sources that are deemed to be reliable but cannot guarantee their accuracy. All information provided to us by others was not audited or verified and was assumed to be correct. Because the procedures were limited, we express no opinion or assurances of any kind on the achievability of any projected information contained herein and this report should not be relied upon for that purpose. -

Reported in the Court of Special Appeals Of

REPORTED IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 532 September Term, 2008 COMPTROLLER OF THE TREASURY v. JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY Eyler, Deborah S., Wright, Moylan, Charles E., Jr. (Ret'd, Specially Assigned), JJ. Opinion by Eyler, Deborah S., J. Filed: June 9, 2009 Johns Hopkins University (“Hopkins” or “the University”), the appellee, applied for a refund of admissions and amusement taxes it paid to Baltimore City, as collected by the Comptroller of the Treasury (“the Comptroller”), the appellant, on gross receipts from ticket sales to intercollegiate men’s lacrosse games in 2002, 2003, and 2004. When the Comptroller denied the refund request, Hopkins filed a challenge in the Maryland Tax Court. Ultimately, the Tax Court granted the refund. After that decision was affirmed on judicial review by the Circuit Court for Baltimore City, the Comptroller noted this appeal, posing one question for review: Did the Maryland Tax Court commit legal error when it decided that the gross receipts from intercollegiate athletic events were used exclusively for an educational purpose? For the reasons that follow, we uphold the decision of the Tax Court and therefore shall affirm the judgment of the circuit court. FACTS AND PROCEEDINGS In an evidentiary hearing before the Tax Court, on September 13, 2006, Hopkins called witnesses Debra Sorandes, Senior Tax Accountant for the University, and Tom Calder, Director of Athletics and Recreation for Hopkins, and the Comptroller called witness Theresa Trentler, Refund Supervisor. The basic first-level facts were not in dispute. On March 7, 2005, Hopkins filed a written refund application with the Comptroller, seeking to recover $40,672.40 in admissions and amusement taxes it had paid on ticket sales receipts from intercollegiate men’s lacrosse games between February 2002 and June 2004. -

The Johns Hopkins University Café Q Silk Road Express Ambassador Dining Room Ban Thai Boccacio Brewer's Art Café Hon The

two thousand four Commencement The Johns Hopkins University SUGGESTED RESTAURANTS HOMEWOOD CAMPUS Brewer’s Art Café Q 1106 N. Charles Street (downtown Milton S. Eisenhower Library, Baltimore), 410-547-6925 1st floor, 7 a.m.–9 p.m. Stylish pub fare. Opens at 4:30 p.m. Salads, fruit, sandwiches, beverages, coffee, Reservations accepted. $$ and baked goods. The “Buzz” Café Hon Bloomberg Center for Physics and 1002 W. 36th Street (University area), Astronomy, 1st floor, 8:30 a.m.–1 p.m. 410-243-1230 Sushi, Italian sodas, coffee, bagels, Home-style food in Hampden. Lunch and croissants, muffins, desserts, sandwiches, dinner. No reservations. Possible JHU and salads. discount. $ Silk Road Express Mattin Center, 2 p.m.–midnight The Carlyle Club Muffins, bagels, croissants, desserts, 500 W. University Parkway sandwiches, salads, soups, coffee, and (in The Carlyle, University area), beverages. 410-243-5454 Authentic Lebanese cuisine. OFF-CAMPUS Lunch and dinner. Closed Mondays. Reservations required. $$ for lunch; Ambassador Dining Room $$$ for dinner. 3811 Canterbury Road (University area), 410-366-1484 Charleston Northern Royal Indian cuisine served inside 1000 Lancaster Street, Sylvan Learning or outside in the Ambassador Gardens. Center Bldg. (downtown Baltimore), Lunch and dinner. Reservations recom- 410-332-7373 mended. $$$ Zagat Guide–listed chef Cindy Wolf’s Ban Thai premiere Baltimore restaurant. American Southern haute cuisine. Dinner only. 340 N. Charles Street (downtown Advance reservations required. $$$$ Baltimore), 410-727-7971 Authentic Thai dishes, attractive setting in Cheesecake Factory downtown Charles Street shopping district. Pratt Street Pavilion, Harborplace (Inner Lunch and dinner. Reservations not Harbor), 410-234-3990 necessary. $$ Long, diverse menu, huge portions, Boccacio 1- to 2-hour wait at lunch and dinner.