INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hell on Earth… Alex

Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library 02:2000 No21 $1/50p Hell on Earth… Alex. Berkman’s first speech after his release from Alexanderjail Berkman was released from prison on May Sheriff, “he can speak half a dozen languages”. Then 18, and went direct to Detroit, Mich., where he the officer of the workhouse came up to me and said; delivered the following address on May 22: “young man, let me tell you something: we only speak I suppose you have heard the story about the one language here, and damn little at that.” Under such little boy who was asked one day by his mother circumstances you will understand that I am somewhat whether he had said his morning prayer, and little out of practice: in fact, I have almost forgotten how to Johnny replied that he had, and then asked: “Mother, talk at all. And, therefore, I am not going to make a why is it my prayer is so long? Mary is such a big girl, so•called speech to you tonight, but I just want to talk and she has only got a little prayer”. His mother said, to you a little. “why, Johnny, how’s that?” and then the little boy told First of all, I want to tell you how glad I am to her that when Mary was called in the morning she be again in your midst. And you, my friends, are prayed like this: “Oh, Lord. I hate to get up.” That’s evidently pleased to see me, but, great as your pleasure how I felt when my name was called. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

EXPLORATIONS INTO a COMPLICATED STORY – OURS Voices, Experiences and Accounts of Disability at the University of Bologna

EXPLORATIONS INTO A COMPLICATED STORY – OURS Voices, experiences and accounts of disability at the University of Bologna edited by Nicola Bardasi and Cristiana Natali translated by Nicola Bardasi, Yuri Lysenko, Eleonora Perugini, Zazie Alberta Piva, Gabriele Savioli reviewed by Peter Henderson 1 Original title: Io a loro ho cercato di spiegare che è una storia complicate la nostra. Voci, esperienze, testimonianze sulla disabilità all’Università di Bologna Published by: Bononia University Press Via Ugo Foscolo 7, 40123 Bologna tel. (+39) 051 232 882 fax (+39) 051 221 019 © 2018 Bononia University Press ISBN 978-88-6923-357-9 www.buponline.com [email protected] First edition: July 2018 Cover design: Paola Bosi English version: March 2020 (updated June 2020) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Cristiana Natali How dancing gave me a hand 7 Maria Paola Chiaverini Sensory rediscovery of the world 9 Rocco Pessolano A story of deafness: a University experience 16 Cecilia Bacconi Equality and difference 19 Francesco Nurra The secret club 22 Anonymous The long journey 28 Michela Ricci Malerbi When disability is invisible 35 Jennifer Pallotta Patience and irony 38 Luca Mozzachiodi Disability and University 47 Enrico Franceschi I only had to get experience, instead I found a friend 53 Luca G. De Sandoli Interview with Matteo Corvino 61 Nicola Bardasi Interview with Francesco Musolesi 65 Nicola Bardasi My story 72 Giulia Baraldi Physical (and then also psychological) disadvantages 78 Anonymous A learning curve 80 Fabiola Girneata APPENDIX Project presentation letter 83 Selected anthropological bibliography 85 by Nicola Bardasi The authors 88 Introduction Cristiana Natali Translated by Gabriele Savioli Maria Paola has only one hand – the right one. -

Water Quality Attribution and Simulation of Non-Point Source Pollution Load Fux in the Hulan River Basin Yan Liu1,2, Hongyan Li1,2*, Geng Cui3 & Yuqing Cao1,2

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Water quality attribution and simulation of non-point source pollution load fux in the Hulan River basin Yan Liu1,2, Hongyan Li1,2*, Geng Cui3 & Yuqing Cao1,2 Surface water is the main source of irrigation and drinking water for rural communities by the Hulan River basin, an important grain-producing region in northeastern China. Understanding the spatial and temporal distribution of water quality and its driving forces is critical for sustainable development and the protection of water resources in the basin. Following sample collection and testing, the spatial distribution and driving forces of water quality were investigated using cluster analysis, hydrochemical feature partitioning, and Gibbs diagrams. The results demonstrated that the surface waters of the Hulan River Basin tend to be medium–weakly alkaline with a low degree of mineralization and water-rock interaction. Changes in topography and land use, confuence, application of pesticides and fertilizers, and the development of tourism were found to be important driving forces afecting the water quality of the basin. Non-point source pollution load fuxes of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) were simulated using the Soil Water and Assessment Tool. The simulation demonstrated that the non-point source pollution loading is low upstream and increases downstream. The distributions of N and P loading varied throughout the basin. The fndings of this study provide information regarding the spatial distribution of water quality in the region and present a scientifc basis for future pollution control. Rivers are an important component of the global water cycle, connecting the two major ecosystems of land and sea and providing a critical link in the biogeochemical cycle. -

Three Prominences1

THE THREE PROMINENCES1 Yizhong Gu The political-aesthetic principle of the “three prominences” (san tuchu 三突出) was the formula foremost in governing proletarian literature and art during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) (hereafter CR). In May 1968, Yu Huiyong 于会泳 initially proposed and defined the principle in this way: Among all characters, give prominence to the positive characters; among the positive characters, give prominence to the main heroic characters; among the main characters, give prominence to the most important character, namely, the central character.2 As the main composer of the Revolutionary Model Plays, Yu Hui- yong had gone through a number of ups and downs in the official hierarchy before finally receiving favor from Jiang Qing 江青, wife of Mao Zedong. Yu collected plenty of Jiang Qing’s concrete but scat- tered directions on the Model Plays and tried to summarize them in an abstract and formulaic pronouncement. The principle of three prominances was supposed to be applicable to all the Model Plays and thus give guidance for the creation of future proletarian artworks. Summarizing the gist of Jiang’s instruction, Yu observed, “Comrade Jiang Qing lays strong emphasis on the characterization of heroic fig- ures,” and therefore, “according to Comrade Jiang Qing’s directions, we generalize the ‘three prominences’ as an important principle upon which to build and characterize figures.”3 1 This essay owes much to invaluable encouragement and instruction from Profes- sors Ban Wang of Stanford University, Tani Barlow of Rice University, and Yomi Braester of the University of Washington. 2 Yu Huiyong, “Rang wenyi wutai yongyuan chengwei xuanchuan maozedong sixiang de zhendi” (Let the stage of art be the everlasting front to propagate the thought of Mao Zedong), Wenhui Bao (Wenhui daily) (May 23, 1968). -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

Cijhar 22 FINAL.Pmd

1 1 Vijayanagara as Reflected Through its Numismatics *Dr. N.C. Sujatha Abstract Vijayanagara an out-and-out an economic state which ushered broad outlay of trade and commerce, production and manufacture for over- seas markets. Its coinage had played definitely a greater role in tremendous economic activity that went on not just in India, but also across the continent. Its cities were bustled with traders and merchandise for several countries of Europe and Africa. The soundness of their economy depended on a stable currency system. The present paper discusses the aspects relating to the coinage of Vijayanagara Empire and we could enumerate from these coins about their administration. Its currency system is a wonderful source for the study of its over-all activities of administration, social needs, religious preferences, vibrant trade and commerce and traditional agriculture and irrigation Key words : Empire, Administration, Numismatics, Currency, trade, commerce, routes, revenue, land-grants, mint, commercial, brisk, travellers, aesthetic, fineness, abundant, flourishing, gadyana, Kasu, Varaha, Honnu, panam, Pardai, enforcement, Foundation of Vijayanagara Empire in a.d.1336 is an epoch in the History of South India. It was one of the great empires founded and ruled for three hundred years, and was widely extended over peninsular India. It stood as a bulwark against the recurring invasions from the Northern India. The rule Vijayanagara is the most enthralling period for military exploits, daring conquests, spread of a sound administration. Numismatics is an important source for the study of history. At any given time, the coins in circulation can throw lot of light on then prevalent situation. -

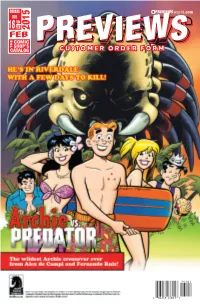

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Master's Degree in Oriental Asian Languages and Civilizations Final

Master’s Degree in Oriental Asian Languages and Civilizations Final Thesis A Space of Her Own. Configurations of feminist imaginative spaces in five post-May Fourth Chinese women writers: Ding Ling, Xiao Hong, Yang Gang, Zhang Ailing, Fengzi. Supervisor Ch. Prof. Nicoletta Pesaro Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Federica Passi Graduand Alessandra Di Muzio 834369 Academic Year 2019 / 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 前言 1 INTRODUCTION The spatial quest of post-May Fourth Chinese women writers (1927-1949) 4 1. Modernity and the new (male) subjectivity 4 2. May-Fourth (1917-1927) Chinese women writers, or modernity denied 6 3. Women, space and the nei 内/wai 外 dichotomy in China 11 4. Who we talk about when we talk about ‘woman’ in traditional, pre-modern China 12 5. Late modern (1927-1949) Chinese women writers, or fighting against erasure 14 6. Negotiating space within a man's world 21 7. Centre, margin and Chinese specificity in the global cultural context of modernity 26 CHAPTER ONE Dark mirage: Ding Ling’s Ahmao guniang 阿毛姑娘 (The girl named Ahmao) and the opacity of woman’s subjectivity 30 1. A feminist upbringing 30 2. Nüxing, darkness and enlightenment 33 3. Shadowscape: Ahmao guniang and her quest for subjectivity 37 4. Woman, voyeurism and the mirage of modernity 41 5. The fractured distance between dreams and reality 44 6. Awareness comes through another woman 49 7. Nüxing and future anteriority 52 8. The shift in space politics and the negative critical appraisal on Ding Ling's first literary phase 57 CHAPTER TWO Watermark: Xiao Hong’s Qi’er 弃儿 (Abandoned Child) and the fluid resilience of woman 62 1. -

Democracy in the Cities: a New Proposal for Chinese Reform

Bloch and TerBush: Democracy in the Cities: A New Proposal for Chinese Reform DEMOCRACY IN THE CITIES: A NEW PROPOSAL FOR CHINESE REFORM DAVID S. BLOCH* THOMAS TERBUSH** [I]t has been no easy job for a big developing country like China with a population of nearly 1.3 billion to have so considerably improved its hu- man rights situation in such a short period of time. -President Hu Jintao, People's Republic of China.' I. THE DILEMMA OF CHINESE DEMOCRACY A great deal has been written on the question of Chinese democracy. In practice and theory, democracy in China is enormously significant.2 This is because China is a rising military threat whose interests are often counter to those of the United States, as well as a demographic powerhouse with as much as a quarter of the world's population. In Mainland China, "the current official mythology.., holds that Chi- nese culture and democracy are incompatible."3 Many Mainland Chinese apparently believe that China's Confucian traditions are inconsistent with democratic practices--an idea with a pedigree that traces both to China's Attorney, Gray Cary Ware & Freidenrich LLP, Palo Alto, California; admitted in Cali- fornia and the District of Columbia; B.A., Reed College (41BK); M.P.H., J.D. with honors, The George Washington University; 1997 Fellow in International Trade Law, University In- stitute of European Studies, Turin, Italy. ** Economist and Senior Analyst, Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, California and Tokyo, Japan; M.A., Ph.D., George Mason University. 1. President Hu Jintao, Enhanced Mutual Understanding and Trust Towards a Conserva- tive and Cooperative Relationship Between China and the United States, translated at www.asiasociety.org/speeches/jintao.htm (speech given by then-Vice President Hu Jintao). -

The Generalissimo

the generalissimo ګ The Generalissimo Chiang Kai- shek and the Struggle for Modern China Jay Taylor the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 .is Chiang Kai- shek’s surname ګ The character Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taylor, Jay, 1931– The generalissimo : Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China / Jay Taylor.—1st. ed. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 03338- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Chiang, Kai- shek, 1887–1975. 2. Presidents—China— Biography. 3. Presidents—Taiwan—Biography. 4. China—History—Republic, 1912–1949. 5. Taiwan—History—1945– I. Title. II. Title: Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China. DS777.488.C5T39 2009 951.04′2092—dc22 [B]â 2008040492 To John Taylor, my son, editor, and best friend Contents List of Mapsâ ix Acknowledgmentsâ xi Note on Romanizationâ xiii Prologueâ 1 I Revolution 1. A Neo- Confucian Youthâ 7 2. The Northern Expedition and Civil Warâ 49 3. The Nanking Decadeâ 97 II War of Resistance 4. The Long War Beginsâ 141 5. Chiang and His American Alliesâ 194 6. The China Theaterâ 245 7. Yalta, Manchuria, and Postwar Strategyâ 296 III Civil War 8. Chimera of Victoryâ 339 9. The Great Failureâ 378 viii Contents IV The Island 10. Streams in the Desertâ 411 11. Managing the Protectorâ 454 12. Shifting Dynamicsâ 503 13. Nixon and the Last Yearsâ 547 Epilogueâ 589 Notesâ 597 Indexâ 699 Maps Republican China, 1928â 80–81 China, 1929â 87 Allied Retreat, First Burma Campaign, April–May 1942â 206 China, 1944â 293 Acknowledgments Extensive travel, interviews, and research in Taiwan and China over five years made this book possible.