Traditional Knowledge Systems of India and Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIAN JOURNAL of ECOLOGY Volume 46 Issue-2 June 2019

ISSN 0304-5250 INDIAN JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY Volume 46 Issue-2 June 2019 THE INDIAN ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY INDIAN ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY (www.indianecologicalsociety.com) Past resident: A.S. Atwal and G.S.Dhaliwal (Founded 1974, Registration No.: 30588-74) Registered Office College of Agriculture, Punjab Agricultural University, Ludhiana – 141 004, Punjab, India (e-mail : [email protected]) Advisory Board Kamal Vatta S.K. Singh S.K. Gupta Chanda Siddo Atwal B. Pateriya K.S. Verma Asha Dhawan A.S. Panwar S. Dam Roy V.P. Singh Executive Council President A.K. Dhawan Vice-Presidents R. Peshin S.K. Bal Murli Dhar G.S. Bhullar General Secretary S.K. Chauhan Joint Secretary-cum-Treasurer Vaneet Inder Kaur Councillors A.K. Sharma A. Shukla S. Chakraborti N.K. Thakur Members Jagdish Chander R.S. Chandel R. Banyal Manjula K. Saxexa Editorial Board Chief-Editor Anil Sood Associate Editor S.S. Walia K. Selvaraj Editors M.A. Bhat K.C. Sharma B.A. Gudae Mukesh K. Meena S. Sarkar Neeraj Gupta Mushtaq A. Wani G.M. Narasimha Rao Sumedha Bhandari Maninder K. Walia Rajinder Kumar Subhra Mishra A.M. Tripathi Harsimran Gill The Indian Journal of Ecology is an official organ of the Indian Ecological Society and is published six-monthly in June and December. Research papers in all fields of ecology are accepted for publication from the members. The annual and life membership fee is Rs (INR) 800 and Rs 5000, respectively within India and US $ 40 and 800 for overseas. The annual subscription for institutions is Rs 5000 and US $ 150 within India and overseas, respectively. -

District Statistical Handbook 2018-19

DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK 2018-19 DINDIGUL DISTRICT DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS DISTRICT STATISTICS OFFICE DINDIGUL Our Sincere thanks to Thiru.Atul Anand, I.A.S. Commissioner Department of Economics and Statistics Chennai Tmt. M.Vijayalakshmi, I.A.S District Collector, Dindigul With the Guidance of Thiru.K.Jayasankar M.A., Regional Joint Director of Statistics (FAC) Madurai Team of Official Thiru.N.Karuppaiah M.Sc., B.Ed., M.C.A., Deputy Director of Statistics, Dindigul Thiru.D.Shunmuganaathan M.Sc, PBDCSA., Divisional Assistant Director of Statistics, Kodaikanal Tmt. N.Girija, MA. Statistical Officer (Admn.), Dindigul Thiru.S.R.Arulkamatchi, MA. Statistical Officer (Scheme), Dindigul. Tmt. P.Padmapooshanam, M.Sc,B.Ed. Statistical Officer (Computer), Dindigul Selvi.V.Nagalakshmi, M.Sc,B.Ed,M.Phil. Assistant Statistical Investigator (HQ), Dindigul DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK 2018-19 PREFACE Stimulated by the chief aim of presenting an authentic and overall picture of the socio-economic variables of Dindigul District. The District Statistical Handbook for the year 2018-19 has been prepared by the Department of Economics and Statistics. Being a fruitful resource document. It will meet the multiple and vast data needs of the Government and stakeholders in the context of planning, decision making and formulation of developmental policies. The wide range of valid information in the book covers the key indicators of demography, agricultural and non-agricultural sectors of the District economy. The worthy data with adequacy and accuracy provided in the Hand Book would be immensely vital in monitoring the district functions and devising need based developmental strategies. It is truly significant to observe that comparative and time series data have been provided in the appropriate tables in view of rendering an aerial view to the discerning stakeholding readers. -

Cultural Policing in Dakshina Kannada

Cultural Policing in Dakshina Kannada Vigilante Attacks on Women and Minorities, 2008-09 March, 2009 Report by People’s Union for Civil Liberties, Karnataka (PUCL-K) Publishing history Edition : March, 2009 Published : English Edition : 500 copies Suggested Contribution : Rs. 50 Published by : PUCL-K Cover Design by : Namita Malhotra Printed by : National Printing Press Any part of this Report may be freely reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. PUCL-K only asserts the right to be identified with the reproduced version. Contents Chapter I- Introduction ................................................... 1 1.1 Need and Purpose of the Report 1.2 Background to Dakshina Kannada 1.3 Consolidation of Hindutva Forces in Karnataka 1.4 Methodology Chapter II - Vigilante Attacks in Dakshina Kannada ...... 8 2.1 Amnesia Pub Incident 2.2 Intimidation of Independent Voices 2.3 Valentine’s Day Offensive 2.4 Continuing Attacks with Renewed Impunity Chapter III - Understanding Cultural Policing in Dakhina Kannada ......................................26 3.1 Strategy of Cultural Policing 3.2 Role of Organizations Professing Hindutva 3.3 Role of the Police 3.4 Role of the Media 3.5 Role of the Public 3.6 Impact of Cultural Policing Chapter IV - Cultural Policing leading to Social Apartheid: Violation of the Constitutional Order .......39 Chapter V - Civil Society’s Response to Cultural Policing ...43 5.1 Komu Souharde Vedike (KSV) 5.2 Karnataka Forum for Dignity (KFD) 5.3 Democratic Youth Federation of India (DYFI) 5.4 People’s Movement for Enforcement -

Study of Certain Reproductive and Productive Performance Parameters

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2020; 9(9): 270-274 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Study of certain reproductive and productive TPI 2020; 9(9): 270-274 © 2020 TPI performance parameters of malnad gidda cattle in its www.thepharmajournal.com Received: 21-06-2020 native tract Accepted: 07-08-2020 Murugeppa A Murugeppa A, Tandle MK, Shridhar NB, Prakash N, Sahadev A, Vijaya Associate Professor and Head, Department of Veterinary Kumar Shettar, Nagaraja BN and Renukaradhya GJ Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Veterinary College, Shivamogga, Abstract Karnataka, India The study was conducted to establish baseline information pertaining to productive and reproductive performance of Malnad Gidda and its crossbred in Shivamogga District of Karnataka. The data from 286 Tandle MK animals reared by 98 farmers from Thirtahalli, Hosanagara and Sagara taluks of Shivamogga district Director of Instruction (PGS), Karnataka Veterinary Animal were collected through a structured questionnaire. The parameters such as age at puberty (25.15±0.29 and Fisheries University, Bidar, months); age at first calving (39.32±2.99 months); dry period (6.22±1.26 months); calving interval Karnataka, India (13.68±2.55 months); gestation period (282.14±9.03 days); service period (136.73±10.03 days); lactation length (258.22 ± 10.95 days); milk yield per day (3.69±0.32 kg); total milk yield (227.19±8.31 kg); days Shridhar NB to reach peak milk yield (46.19±0.51 day); birth weight of the new born calf (8.71±0.45 kg); time taken Professor and Head, Department for placental expulsion of placenta (4.63±0.39 hours); onset of postpartum estrous (77.64±1.98 days); of Veterinary Pharmacology and Duration of estrous period (15.25±1.67 hours); time of ovulation (15.15 ± 1.7 hours) and length of estrus Toxicology, Veterinary College cycle (22.63±2.96. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

Selection-Criteria-And-Format-Breed Saviour Award 2015.Pdf

Breed Saviour Awards 2015 Breed Saviour Awards are organised by SEVA in association with Honey Bee Network members and National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources, Karnal and sponsored by the National Biodiversity Authority, Chennai. A total of 20 awardees will be selected for the year 2015, each of whom will be awarded with a sum of Rs. 10,000/- and a Certificate. Awardees along with one accompanying person (NGO representative) will be supported for their travel by train (sleeper class) and stay to attend the award ceremony, which is proposed to be convened during February 2016 at NBAGR, Karnal, Haryana. Criteria for Selection: 1. Cases of livestock keepers engaged in breed conservation / improvement, or sustaining conservation through enhanced earning from breed or its products, value addition, breeding services to the society and improving common property resources etc. will be considered. 2. Breeds already registered and also distinct animal populations which are not yet registered will also be considered under this livelihood based award. For each breed, award will be restricted only to two livestock keepers / groups /communities (including earlier 5 rounds of awards starting from 2009); Breeds which have been recognized and awarded during the previous two edition of Breed Saviour Awards are not eligible for inclusion 2015 edtion. These include: Deoni cattle, Kangayam cattle, Pulikulam cattle, Vechur cattle, Bargur cattle, Binjharpuri cattle, Kankrej cattle, Malaimadu cattle, Banni buffalo, Toda buffalo, Marwari camel, Kharai camel, Kachchi camel, Ramnad white sheep, Vembur sheep, Malpura sheep, Mecheri sheep, Deccani sheep, Attapadi black goat, Osmanabadi goat, Kanniyadu goat, Madras Red sheep and Kachaikatti black sheep). -

Bos Indicus) Breeds

Animal Biotechnology ISSN: 1049-5398 (Print) 1532-2378 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/labt20 Complete mitogenome reveals genetic divergence and phylogenetic relationships among Indian cattle (Bos indicus) breeds R. Kumar Pramod, Dinesh Velayutham, Sajesh P. K., Beena P. S., Anil Zachariah, Arun Zachariah, Chandramohan B., Sujith S. S., Ganapathi P., Bangarusamy Dhinoth Kumar, Sosamma Iype, Ravi Gupta, Sam Santhosh & George Thomas To cite this article: R. Kumar Pramod, Dinesh Velayutham, Sajesh P. K., Beena P. S., Anil Zachariah, Arun Zachariah, Chandramohan B., Sujith S. S., Ganapathi P., Bangarusamy Dhinoth Kumar, Sosamma Iype, Ravi Gupta, Sam Santhosh & George Thomas (2018): Complete mitogenome reveals genetic divergence and phylogenetic relationships among Indian cattle (Bos indicus) breeds, Animal Biotechnology, DOI: 10.1080/10495398.2018.1476376 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2018.1476376 View supplementary material Published online: 23 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=labt20 ANIMAL BIOTECHNOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2018.1476376 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Complete mitogenome reveals genetic divergence and phylogenetic relationships among Indian cattle (Bos indicus) breeds R. Kumar Pramoda, Dinesh Velayuthama, Sajesh P. K.a, Beena P. S.a, Anil Zachariahb, Arun Zachariahc, Chandramohan B.d, Sujith S. S.a, Ganapathi P.e, Bangarusamy Dhinoth Kumara, Sosamma Iypeb, Ravi Guptaf, Sam Santhoshg and George Thomasg aAgriGenome Labs Pvt. Ltd., Smart City Kochi, India; bVechur Conservation Trust, Thrissur, India; cDepartment of Forest and Wildlife, Wayanad, Kerala, India; dNational Institute of Science Education and Research, Jatni, India; eBargur Cattle Research Station, Tamil Nadu Veterinary Animal Sciences University, Chennai, India; fMedgenome Labs Pvt. -

Dos-Fsos -District Wise List

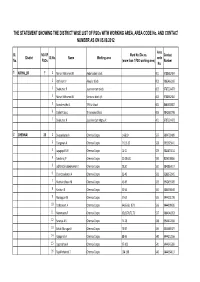

THE STATEMENT SHOWING THE DISTRICT WISE LIST OF FSOs WITH WORKING AREA, AREA CODE No. AND CONTACT NUMBER AS ON 05.09.2012 Area Sl. NO.OF Ward No./Div.no. Contact District Sl.No. Name Working area code No. FSOs (more than 1 FSO working area) Number No. 1 ARIYALUR 7 1 Nainar Mohamed.M Andimadam block 001 9788682404 2 Rathinam.V Ariyalur block 002 9865463269 3 Sivakumar.P Jayankondam block 003 9787224473 4 Nainar Mohamed.M Sendurai block i/c 004 9788682404 5 Savadamuthu.S T.Palur block 005 8681920807 6 Stalin Prabu.L Thirumanur block 006 9842387798 7 Sivakumar.P Jayankondam Mpty i/c 401 9787224473 2 CHENNAI 25 1 Sivasankaran.A Chennai Corpn. 1-6&10 527 9894728409 2 Elangovan.A Chennai Corpn. 7-9,11-13 528 9952925641 3 Jayagopal.N.H Chennai Corpn. 14-21 529 9841453114 4 Sundarraj.P Chennai Corpn. 22-28 &31 530 8056198866 5 JebharajShobanaKumar.K Chennai Corpn. 29,30 531 9840867617 6 Chandrasekaran.A Chennai Corpn. 32-40 532 9283372045 7 Muthukrishnan.M Chennai Corpn. 41-49 533 9942495309 8 Kasthuri.K Chennai Corpn. 50-56 534 9865390140 9 Mariappan.M Chennai Corpn. 57-63 535 9444231720 10 Sathasivam.A Chennai Corpn. 64,66-68 &71 536 9444909695 11 Manimaran.P Chennai Corpn. 65,69,70,72,73 537 9884048353 12 Saranya.A.S Chennai Corpn. 74-78 538 9944422060 13 Sakthi Murugan.K Chennai Corpn. 79-87 539 9445489477 14 Rajapandi.A Chennai Corpn. 88-96 540 9444212556 15 Loganathan.K Chennai Corpn. 97-103 541 9444245359 16 RajaMohamed.T Chennai Corpn. -

List of Food Safety Officers

LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. Email address Officer /District ANDAMAN & 1. Smti. Sangeeta Naseem South Andaman District Food Safety Office, 09434274484 [email protected] NICOBAR District Directorate of Health Service, G. m ISLANDS B. Pant Road, Port Blair-744101 2. Smti. K. Sahaya Baby South Andaman -do- 09474213356 [email protected] District 3. Shri. A. Khalid South Andaman -do- 09474238383 [email protected] District 4. Shri. R. V. Murugaraj South Andaman -do- 09434266560 [email protected] District m 5. Shri. Tahseen Ali South Andaman -do- 09474288888 [email protected] District 6. Shri. Abdul Shahid South Andaman -do- 09434288608 [email protected] District 7. Smti. Kusum Rai South Andaman -do- 09434271940 [email protected] District 8. Smti. S. Nisha South Andaman -do- 09434269494 [email protected] District 9. Shri. S. S. Santhosh South Andaman -do- 09474272373 [email protected] District 10. Smti. N. Rekha South Andaman -do- 09434267055 [email protected] District 11. Shri. NagoorMeeran North & Middle District Food Safety Unit, 09434260017 [email protected] Andaman District Lucknow, Mayabunder-744204 12. Shri. Abdul Aziz North & Middle -do- 09434299786 [email protected] Andaman District 13. Shri. K. Kumar North & Middle -do- 09434296087 kkumarbudha68@gmail. Andaman District com 14. Smti. Sareena Nadeem Nicobar District District Food Safety Unit, Office 09434288913 [email protected] of the Deputy Commissioner , m Car Nicobar ANDHRA 1. G.Prabhakara Rao, Division-I, O/o The Gazetted Food 7659045567 [email protected] PRDESH Food Safety Officer Srikakulam District Inspector, Kalinga Road, 2. K.Kurmanayakulu, Division-II, Srikakulam District, 7659045567 [email protected] LIST OF FOOD SAFETY OFFICER State S.No Name of Food Safety Area of Operation Address Contact No. -

In the High Court of Karnataka Dharwad Bench

R IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA DHARWAD BENCH DATED THIS THE 24TH DAY OF AUGUST, 2020 BEFORE THE HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE E.S. INDIRESH MFA No.100918/2020 (GM-CPC) c/w MFA NO.101088/2020 MFA NO.100918 OF 2020 Between : 1. Shree Samsthana Mahabaleshwara Deva Gokarna, Rep. by Shree Raghaveshwara Bharathi Swamiji Aged about 42 years, Peetadhipathi Shri Ramachadrapura Matha, Haniya Village, Hosanagara Taluka Shimoga District Administrative Office Shree Mahabaleshwara Temple Gokarna, Kumta Taluk, Uttara Kannada. 2. Shri Ramachandrapura Matha Rep by Shree Raghaveshwara Bharathi Swamiji, Aged 42 years Peetadhipathi Shri Ramachandrapura Matha Haniya Village, Hosanagara Taluka, Shimoga District, Administrative Office Shree Mahableshwara Temple Gokarna, Kumta Taluk. The Appellant No.1 is represented by the 2 Special Power of Attorney Holder Sri. Ganapati K.Hegde, S/o Krishnaiah Hegde Aged 71 years, Administrator Shree Samsthana Mahabaleshwara Deva, Gokarna, Kumta Taluk, U.K. District. 3. Shri Krishna S/o Ganesh Bhat, Aged 65 years, Chief Executive Officer Shri Ramachandrapura Matha Administartive Office No.2-A J.C.Road, Girinagara First Phase, Bangalore, Rep. by GPA Holder Appellant No.2 i.e. Shri Ramachandrapura Matha. …Appellants (by Shri K.G. Raghavan, Sr. Counsel for Shri Prashant F. Goudar, Advocate) And : 1. U.F.M. Ananthraj S/o Dattatreya Adi Age 56 years, R/o Rathabeedi Gokarna-581 319. 2. U.F.M. Vishweshwar S/o Gopal Adi Age 61 years, R/o Rathabeedi Gokarna-581 319. 3. U.F.M. Laxminarayana S/o Venkatarama Adi Age 49 years, R/o Rathabeedi Gokarna-581 319. 4. U.F.M. -

Patterns of Forest Use and Its Influence on Degraded Dry Forests: a Case

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Department für Ökosystem-und Landschaftsmanagement Lehrstuhl für Waldbau und Forsteinrichtung Patterns of forest use and its influence on degraded dry forests: A case study in Tamil Nadu, South India Joachim Schmerbeck Vollständiger Abdruck der von dem Promotionsausschuss der Studienfakultät für Forstwissenschaft und Ressourcenmanagement an der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Forstwissenschaft (Dr. rer. silv.) genehmigten Dissertation Freising-Weihenstephan, November 2003 Gedruckt mit der Unterstützung von Dr. Berthold Schmerbeck Erstkorrektor: Prof. Dr. R. Mosandl Zweitkorrektor: PD Dr. K. Seeland Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.12.02 Copyright Shaker Verlag 2003 Printed in Germany ISBN 3-8322-2214-6 ISSN 1615-1674 „IN THE FIRST PLACE WE HAVE TO FIND SOLUTIONS FOR MAN; NOT FOR THE FOREST” Anonymus For my parents Acknowledgement As I started this study I was not aware of the dimensions of the work I had chosen to undertake. To make it a success, was not just a matter of raising funds and going to India. Struggle in the German and Indian administrative jungle, slow progress of simple things, stressful fieldwork, broken computers, dealing with new software as well as deep valleys of frustration and loneliness were my companions. Without the assistance of so many good people, I would not have been able to conduct this study. To rank these persons according to their importance is impossible. So many would hold the first position. Therefore I wish to mention them in the order, in which they became involved in my project. -

Study on the Effect of Heat Treatment on Chemical Composition of Milk

The Pharma Innovation Journal 2018; 7(11): 132-135 ISSN (E): 2277- 7695 ISSN (P): 2349-8242 NAAS Rating: 5.03 Study on the effect of heat treatment on chemical TPI 2018; 7(11): 132-135 © 2018 TPI composition of milk among native and cross bred cows www.thepharmajournal.com Received: 01-09-2018 Accepted: 05-10-2018 Ashok Kumar Devarasetti, P Eswara Prasad, Y Narsimha Reddy, BDP Ashok Kumar Devarasetti Kala Kumar and K Padmaja Assistant Professor, Department of Veterinary Biochemistry, P.V. Abstract Narsimha Rao Telangana An experiment was conducted to study the milk composition of native breeds (Sahiwal, Ongole & Veterinary University, Punganur) and cross bred cows (HF & Jersey). Milk samples of eight healthy cows each of five cattle Hyderabad, Telangana, India breeds, each breed were divided into four groups based on heat treatment as group I – Control (Raw 0 0 P Eswara Prasad milk); group II – Heating milk at 60 C /30 min. (LTLT); group III - Heating milk at 72 C/15 sec. 0 Professor &University Head, (HTST) and group IV - Heating milk at 135 C/5 sec. (UHT), and analyzed for chemical composition (fat Department of Veterinary %, SNF %, Lactose and Protein). The results showed that, the milk of Punganur, Ongole and Sahiwal Biochemistry, College of breed cows is superior in terms of its chemical composition and has potential to withstand for heat Veterinary Science, Tirupati, treatment when compared to Jersey and HF cross bred cows. The results of the study further Andhra Pradesh, India demonstrated that heating the milk beyond 600C will denature the proteins, lactose and reduced the fat and SNF % in cross bred when compared to native breeds.