'The Great Handel Chorus' To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

A Listening Guide for the Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini

A Listening Guide for The Indispensable Composers by Anthony Tommasini 1 The Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide Anthony Tommasini A listening guide INTRODUCTION: The Greatness Complex Bach, Mass in B Minor I: Kyrie I begin the book with my recollection of being about thirteen and putting on a recording of Bach’s Mass in B Minor for the first time. I remember being immediately struck by the austere intensity of the opening choral singing of the word “Kyrie.” But I also remember feeling surprised by a melodic/harmonic shift in the opening moments that didn’t do what I thought it would. I guess I was already a musician wanting to know more, to know why the music was the way it was. Here’s the grave, stirring performance of the Kyrie from the 1952 recording I listened to, with Herbert von Karajan conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. Though, as I grew to realize, it’s a very old-school approach to Bach. Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Vienna Philharmonic (12:17) Today I much prefer more vibrant and transparent accounts, like this great performance from Philippe Herreweghe’s 1996 recording with the chorus and orchestra of the Collegium Vocale, which is almost three minutes shorter. Philippe Herreweghe, conductor; Collegium Vocale Gent (9:29) Grieg, “Shepherd Boy” Arthur Rubinstein, piano Album: “Rubinstein Plays Grieg” (3:26) As a child I loved “Rubinstein Plays Grieg,” an album featuring the great pianist Arthur Rubinstein playing piano works by Grieg, including several selections from the composer’s volumes of short, imaginative “Lyrical Pieces.” My favorite was “The Shepherd Boy,” a wistful piece with an intense middle section. -

Monteverdi the Beauty of Monteverdi

The Beauty of Monteverdi The Beauty of Monteverdi 2 Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) 1 L’Orfeo: Toccata 1:36 12 Zefiro torna, e di soavi accenti (Scherzi musicali, cioè arie, et madrigali in stil recitativo) 6:47 ENGLISH BAROQUE SOLOISTS · JOHN ELIOT GARDINER Text: Ottavio Rinuccini ANNA PROHASKA soprano · MAGDALENA KOŽENÁ mezzo-soprano Vespro della Beata Vergine LA CETRA BAROCKORCHESTER BASEL · ANDREA MARCON harpsichord and conductor 2 Lauda Jerusalem a 7 3:48 13 (Ottavo libro de’ madrigali: Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi) 8:00 3 Duo seraphim a 3 6:44 Lamento della ninfa Text: Ottavio Rinuccini 4 Nisi Dominus a 10 4:36 MAGDALENA KOŽENÁ mezzo-soprano 5 Pulchra es a 2 3:57 JAKOB PILGRAM · MICHAEL FEYFAR tenor · LUCA TITTOTO bass MARINELLA PENNICCHI � · ANN MONOYIOS � soprano LA CETRA BAROCKORCHESTER BASEL · ANDREA MARCON harpsichord and conductor MARK TUCKER � · NIGEL ROBSON � · SANDRO NAGLIA � tenor · THE MONTEVERDI CHOIR � , � JAKOB LINDBERG � chitarrone, � lute · DAVID MILLER �, � · CHRISTOPHER WILSON � chitarrone 14 Io mi son giovinetta (Quarto libro de’ madrigali) 2:14 ENGLISH BAROQUE SOLOISTS · HIS MAJESTYS SAGBUTTS & CORNETTS · JOHN ELIOT GARDINER Text: Giovanni Battista Guarini Recorded live at the Basilica di San Marco, Venice EMMA KIRKBY · EVELYN TUBB soprano · MARY NICHOLS alto JOSEPH CORNWELL tenor · RICHARD WISTREICH bass L’Orfeo CONSORT OF MUSICKE · ANTHONY ROOLEY Libretto: Alessandro Striggio jr 6 “Rosa del ciel” (Orfeo) … “Io non dirò qual sia” (Euridice) … 4:30 15 Parlo, miser, o taccio (Settimo libro de’ madrigali) 4:42 Balletto: “Lasciate i monti” … “Vieni, Imeneo” (Coro) Text: Giovanni Battista Guarini 7 Sinfonia … “Ecco pur ch’a voi ritorno” (Orfeo) 0:50 EMMA KIRKBY · JUDITH NELSON soprano · DAVID THOMAS bass CONSORT OF MUSICKE · ANTHONY ROOLEY 8 “Mira ch’a sé n’alletta” (Pastore I & II) … “Dunque fa’ degni, Orfeo” (Coro) 2:18 9 “Qual onor di te fia degno” … “O dolcissimi lumi” (Orfeo) – 3:16 16 Laetatus sum (Messa, salmi concertati e parte da capella, et letanie della B. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Report to Donors 2012 Table of Contents

Report to Donors 2012 Table of Contents Mission 2 Board of Trustees 3 Letter from the Director 4 Letter from the President 5 Exhibitions 6 Public, Educational, and Scholarly Programs 9 Gifts to the Collection 12 Statement of Financial Position 14 Donors 15 Planned Giving 23 Staff 24 Mission Board of Trustees he mission of The Morgan Library & Museum is to Lawrence R. Ricciardi Karen H. Bechtel ex officio preserve, build, study, present, and interpret a collection President Rodney B. Berens William T. Buice III Susanna Borghese William M. Griswold T of extraordinary quality in order to stimulate enjoyment, James R. Houghton T. Kimball Brooker William James Wyer excite the imagination, advance learning, and nurture creativity. Vice President Karen B. Cohen Flobelle Burden Davis life trustees A global institution focused on the European and American Richard L. Menschel Geoffrey K. Elliott William R. Acquavella traditions, the Morgan houses one of the world’s foremost Vice President Brian J. Higgins Walter Burke Clement C. Moore II Haliburton Fales, 2d collections of manuscripts, rare books, music, drawings, and George L. K. Frelinghuysen John A. Morgan S. Parker Gilbert, ancient and other works of art. These holdings, which represent Treasurer Diane A. Nixon President Emeritus the legacy of Pierpont Morgan and numerous later benefactors, Cosima Pavoncelli Drue Heinz Thomas J. Reid Peter Pennoyer Lawrence Hughes comprise a unique and dynamic record of civilization as well as Secretary Cynthia Hazen Polsky Herbert Kasper an incomparable repository of ideas and of the creative process. Katharine J. Rayner Herbert L. Lucas Annette de la Renta Charles F. -

Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra for Seasons 1946-47 to 2006-07 Last Updated April 2007

Artistic Director NEVILLE CREED President SIR ROGER NORRINGTON Patron HRH PRINCESS ALEXANDRA Concerts with the London Philharmonic Orchestra For Seasons 1946-47 To 2006-07 Last updated April 2007 From 1946-47 until April 1951, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in the Royal Albert Hall. From May 1951 onwards, unless stated otherwise, all concerts were given in The Royal Festival Hall. 1946-47 May 15 Victor De Sabata, The London Philharmonic Orchestra (First Appearance), Isobel Baillie, Eugenia Zareska, Parry Jones, Harold Williams, Beethoven: Symphony 8 ; Symphony 9 (Choral) May 29 Karl Rankl, Members Of The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Kirsten Flagstad, Joan Cross, Norman Walker Wagner: The Valkyrie Act 3 - Complete; Funeral March And Closing Scene - Gotterdammerung 1947-48 October 12 (Royal Opera House) Ernest Ansermet, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Clara Haskil Haydn: Symphony 92 (Oxford); Mozart: Piano Concerto 9; Vaughan Williams: Fantasia On A Theme Of Thomas Tallis; Stravinsky: Symphony Of Psalms November 13 Bruno Walter, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Isobel Baillie, Kathleen Ferrier, Heddle Nash, William Parsons Bruckner: Te Deum; Beethoven: Symphony 9 (Choral) December 11 Frederic Jackson, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Ceinwen Rowlands, Mary Jarred, Henry Wendon, William Parsons, Handel: Messiah Jackson Conducted Messiah Annually From 1947 To 1964. His Other Performances Have Been Omitted. February 5 Sir Adrian Boult, The London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joan Hammond, Mary Chafer, Eugenia Zareska, -

The Academy of Ancient Music CHRISTOPHER HOGWOOD Director

THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The Academy of Ancient Music CHRISTOPHER HOGWOOD Director EMMA KIRKBY, Soprano DAVID THOMAS, Bass THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 14, 1985, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Water Music..................................................... HANDEL Horn Suite in F major Overture: largo, allegro Menuct for French Horn Adagio c staccato Bourree Allegro Hornpipe Air: presto Flute Suite in G major Menuet Menuets I and II Rigaudon Country Dance Trumpet Suite in D major Allegro Lcntcmcnt Alia Hornpipe Air Trumpet Menuet INTERMISSION Cantata, Apollo and Dafne ........................................ HANDEL EMMA KIUKBY, Soprano DAVID THOMAS, Bass RACHEL BROWN, flute obbligato CLARE SHANKS, oboe obbligato Hypcrioii and L'Oiscmi-Lyrc Records. Sixtieth Concert of the 106th Season Special Concert Program Notes by Christopher Hogwood Water Music .................................... GEORGE FRIDEUIC HANDEL (1685-1759) "On 15 July, 1717, it was reported that 'at about 8,' the King took Water at Whitehall in an open Barge, and went up the River towards Chelsea. Many other Barges with Persons of Quality attended. A City Company's Barge was employ'd for the Musick, wherein were 50 Instruments of all sorts, who play'd all the way from Lambeth the finest Symphonies, compos'd express for this Occasion by Mr. Hendel; which his Majesty liked so well that he caus'd it to be plaid over three times in going and returning. At Eleven his Majesty went ashore at Chelsea, where a Supper was prepar'd, -

Monteverdi Choir Copy

Monteverdi Choir & Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique Wednesday, January 14, 8 pm, 2004 Zellerbach Hall Sir John Eliot Gardiner, conductor and artistic director PROGRAM George Frideric Handel Coronation Anthem No. 1, Zadok the Priest, for Chorus and Orchestra, HWV 258 Andante maestoso – A tempo ordinario Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Vesperae Solennes de Confessore for Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass Soloists, Chorus, and Orchestra, K. 339 Dixit Dominus: Allegro vivace Confitebor: Allegro Beatus Vir: Allegro vivace Laudate Pueri Laudate Dominum: Andante ma un poco sostenuto Magnificat: Adagio – Allegro INTERMISSION Joseph Haydn Mass in B-flat Major, Heiligmesse (Holy Mass), for Two Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Two Bass Soloists, Chorus, and Orchestra, Hob. XXII:10, Sancti Bernardi de Offida (St. Bernard of Offida) Kyrie: Adagio – Allegro moderato (Chorus) Gloria: Vivace (Chorus) Gratias agimus: Allegretto (Soloists and Chorus) Qui tollis: Più allegro (Chorus) Quoniam tu solus sanctus: Vivace (Chorus) Credo: Allegro (Chorus) Et incarnatus est: Adagio (Soloists and Chorus) Et resurrexit: Allegro (Chorus) Et vitam venturi saeculi: Vivace assai (Chorus) Sanctus: Adagio (Chorus) Benedictus: Moderato (Chorus) Agnus Dei: Adagio (Chorus) Dona nobis pacem: Allegro (Chorus) This performance has been made possible, in part, by members of the Cal Performances Producers Circle. Cal Performances thanks the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and the Zellerbach Family Foundation for their generous support. Cal Performances receives additional funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency that supports the visual, literary, and performing arts to benefit all Americans, and the California Arts Council, a state agency. Coronation Anthem No. 1, Zadok the Priest (HWV 258) George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) One of the last acts of King George I before his unexpected death on June 11, 1727, during a visit to Germany, was to sign the papers awarding Handel British citizenship. -

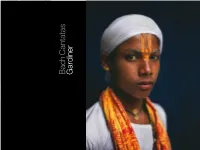

B Ach C Antatas G Ardiner

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 3: Tewkesbury/Mühlhausen SDG141 COVER SDG141 CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass For the Fifth Sunday after Trinity Gott ist mein König BWV 71 C CD 2 62:12 Aus der Tiefen rufe ich, Herr, zu dir BWV 131 M Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten BWV 93 Y Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden BWV 88 K Joanne Lunn soprano, William Towers alto Kobie van Rensburg tenor, Peter Harvey bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Tewkesbury Abbey, 16 July 2000 Blasiuskirche, Mühlhausen, 23 July 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 3 SDG 141 P 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01412 5 SDG 141 Bach Cantatas Gardiner 3 Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity 1-6 17:01 Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 7-12 14:41 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 13-17 25:06 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 BWV 24, 185, 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto The Monteverdi Choir The English Double Bass Harpsichord Baroque Soloists Valerie Botwright Howard Moody Sopranos Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass Cecelia Bruggemeyer Lucinda Houghton First Violins -

City of Birmingham Choir Concerts from 1964

City of Birmingham Choir concerts from 1964. Concerts were conducted by Christopher Robinson and took place in Birmingham Town Hall with the CBSO unless otherwise stated. Messiah concerts and Carols for All concerts are listed separately. 1964 Mar 17 Vaughan Williams: Overture ‘The Wasps’ Finzi: Intimations of Immortality Vaughan Williams: Dona Nobis Pacem Elizabeth Simon John Dobson Peter Glossop Christopher Robinson conducts the Choir for the first time Jun 6 Britten: War Requiem Heather Harper Wilfred Brown Thomas Hemsley Performed in St Alban’s Abbey Meredith Davies’ final concert as conductor of the Choir Nov 11 & 12 Britten: War Requiem (Nov 11 in Wolverhampton Civic Hall Nov 12 in Birmingham Town Hall) Jacqueline Delman Kenneth Bowen John Shirley-Quirk Boy Choristers of Worcester Cathedral CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold 1965 Feb 27 Rossini: Petite Messe Solennelle Barbara Elsy Janet Edmunds Gerald English Neil Howlett Colin Sherratt (Piano) Harry Jones (Piano) David Pettit (Organ) Performed in the Priory Church of Leominster Mar 11 Holst: The Planets CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold Mar 18 Beethoven: Choral Symphony Jennifer Vyvyan Norma Proctor William McAlpine Owen Brannigan CBSO concert conducted by Hugo Rignold Mar 30 Elgar: The Dream of Gerontius Marjorie Thomas Alexander Young Roger Stalman May 18 Duruflé: Requiem Poulenc: Organ Concerto Poulenc: Gloria Elizabeth Harwood Sybil Michelow Hervey Alan Roy Massey (Organ) 34 Jun 2 Rossini: Petite Messe Solennelle Elizabeth Newman Miriam Horne Philip Russell Derek