A Comparative Study of Select Choral Conductors' Approaches To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Erkki-Sven Tüür

© Kaupo Kikkas Erkki-Sven Tüür Contemporary BIOGRAPHIE Erkki-Sven Tüür Mit einem breit gefächerten musikalischen Hintergrund und einer Vielzahl von Interessen und Einflüssen ist Erkki- Sven Tüür einer der einzigartigsten Komponisten der Zeitgenössischen Musik. Tüür hat 1979 die Rockgruppe In Spe gegründet und bis 1983 für die Gruppe als Komponist, Flötist, Keyboarder und Sänger gearbeitet. Als Teil der lebhaften Szene der Zeitgenössischen Musik Estlands unternahm er instrumentale Studien an der Tallinn Music School, studierte Komposition mit Jaan Rääts an der Estonian Academy of Music und erhielt Unterricht bei Lepo Sumera. Intensive energiereiche Transformationen bilden den Hauptcharakter von Tüürs Werken, wobei instrumentale Musik im Vordergrund seiner Arbeit steht. Bis heute hat er neun Sinfonien, Stücke für Sinfonie- und Streichorchester, neun Instrumentalkonzerte, ein breites Spektrum an Kammermusikwerken und eine Oper komponiert. Tüür möchte mit seiner Musik existenzielle Fragen aufwerfen, vor allem die Frage: „Was ist unsere Aufgabe?“ beschäftigt ihn. Er stellte fest, dass dies eine wiederkehrende Frage von Denkern und Philosophen verschiedener Länder ist. Eins seiner Ziele ist es, die kreative Energie des Hörers zu erreichen. Tüür meint, die Musik als eine abstrakte Form von Kunst ist dazu fähig, verschiedene Visionen für jeden von uns und jedes individuelle Wesen zu erzeugen, denn wir sind alle einzigartig. Sein Kompositionsansatz ähnelt der Art und Weise, mit der ein Architekt ein mächtiges Gebäude wie eine Kathedrale, ein Theater oder einen anderen öffentlichen Ort entwirft. Er meint dennoch, dass die Verantwortung eines Komponisten über die eines Architekten hinausgeht, weil er Drama innerhalb des Raums mit verschiedenen Charakteren und Kräften konstruiert und dabei eine bestimmte, lebende Form von Energie kreiert. -

The Choral Compositions of Arvo Pärt As an Example of “God-Seeking” Through Music in Soviet Russia

Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 59(1-2), 85-101. doi: 10.2143/JECS.59.1.2023428 T©HE 2007 CHORAL by Journal COMPOSITIONS of Eastern Christian OF ARVO Studies. PÄRT All rights reserved. 85 THE CHORAL COMPOSITIONS OF ARVO PÄRT AS AN EXAMPLE OF “GOD-SEEKING” THROUGH MUSIC IN SOVIET RUSSIA TATIANA SOLOVIOVA* 1. EMERGING FROM THE UNDERGROUND OF ‘OFFICIAL ATHEISM’ OF THE SOVIET ERA Arvo Pärt was a representative of the underground music in the former Soviet Union. His music, like the works of many other musicians and art- ists, did not fit within the narrow bosom of Socialist Realism – the prevail- ing ideology of the time.1 He had to struggle in order to write the music he wanted. Nowadays there is no Soviet Empire anymore, and the composi- tions of Pärt represent “the face” of contemporary music. He is one of the few composers whose art music enjoys success similar to that of pop. He is widely known, and his works are being performed all over the world. Arvo Pärt was born in 1935 in Paide, near Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, one of the Western republics within the former USSR. Between the First and the Second World War this little country enjoyed a short period of in- dependence. Life for Pärt till 1980 was inseparably connected with his Motherland Estonia on one hand, and with Russia, which was the political and cultural dominant at that time, on the other hand. Pärt knew and loved national traditions, as well as he knew European and Russian culture: he called the composer Glazunov who taught his teacher Heino Eller ‘my musi- * Tatiana Soloviova studied at Moscow State University and obtained her PhD in His- tory. -

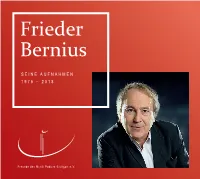

MUSIK PODIUM STUTTGART 2018/19 Frieder Bernius

MUSIK PODIUM STUTTGART 2018/19 Frieder Bernius Kammerchor Stuttgart Barockorchester Stuttgart Hofkapelle Stuttgart Klassische Philharmonie Stuttgart OPEN AIR SCHLOSS SOLITUDE DIRIGENTENAKADEMIE FESTIVAL STUTTGART BAROCK 1 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Musikfreunde, vor Ihnen liegt unser Programm der Saison 2018/19. Es bildet das ab, was man „spezialisierte Vielfalt“ nennen kann und womit wir einen unverwechselbaren künstlerischen Beitrag für unsere Reg ion und darüber hinaus leisten wollen. Dafür brauchen wir Sie: ein Publikum, das sich für individuell interpretierte Meisterwerke eben- so interessiert wie für Unbekanntes, das als Meisterwerk erst noch entdeckt werden will. Überstrahlt wird unsere Saison vom 50-jährigen Jubiläum der Inhalt Gründung des Kammerchors Stuttgart, das wir in diesem Herbst mit zwei ganz unterschiedlichen Programmen feiern wollen: zum einen mit Aufführungen und einer Aufnahme der Missa solemnis von Beethoven, zum anderen einem A-cappella-Programm des 4 50 Jahre Kammerchor Stuttgart Kammerchors, das am 4. November in Zusammenarbeit mit der Jubiläumskonzerte „Akademie für Gesprochenes Wort/Uta Kutter Stiftung“ auch das Ende des ersten Weltkriegs 1918 vor 100 Jahren sowie die Pogrom- 8 Konzerte in Stuttgart und Region nacht 1938 künstlerisch reflektieren will. 18 Konzertkalender Immer wieder ist der Kammerchor Stuttgart zu einem Format für 12 und 16 Solostimmen zurückgekehrt, das auch in der kommenden 20 Musik Podium Stuttgart und seine Ensembles Saison sein Repertoire erweitert und besonders die klassische Mo- 22 Freundeskreis derne einschließt. Eine spezielle Gattung ist auch das Melodram, das die Hofkapelle Stuttgart in der Electra von Christian Cannabich 24 Informationen zum Konzertbesuch einer Schauspielerin gegenüberstellt. Cannabich ist ein Vertreter der sogenannten „Mannheimer Schule“. Mit seiner Electra von 1781 26 CD-Neuerscheinungen wollen wir wieder auf einen Schatz der baden-württembergischen Musikgeschichte aufmerksam machen und für den SWR festhalten. -

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

Spring/Summer 2016

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2016 High-brow, Low-brow, All-brow Bernstein, Gershwin, Ellington, and the Richness of American Music © VICTOR © VICTOR KRAFT by Michael Barrett uch of my professional life has been spent on convincing music lovers Mthat categorizing music as “classical” or “popular” is a fool’s errand. I’m not surprised that people s t i l l c l i n g t o t h e s e d i v i s i o n s . S o m e w h o love classical masterpieces may need to feel reassured by their sophistication, looking down on popular culture as dis- posable and inferior. Meanwhile, pop music fans can dismiss classical music lovers as elitist snobs, out of touch with reality and hopelessly “square.” Fortunately, music isn’t so black and white, and such classifications, especially of new music, are becoming ever more anachronistic. With the benefit of time, much of our country’s greatest music, once thought to be merely “popular,” is now taking its rightful place in the category of “American Classics.” I was educated in an environment that was dismissive of much of our great American music. Wanting to be regarded as a “serious” musician, I found myself going along with the thinking of the times, propagated by our most rigid conservatory student in the 1970’s, I grew work that studiously avoided melody or key academic composers and scholars of up convinced that Aaron Copland was a signature. the 1950’s -1970’s. These wise men (and “Pops” composer, useful for light story This was the environment in American yes, they were all men) had constructed ballets, but not much else. -

Frieder Bernius

Frieder Bernius SEINE AUFNAHMEN 1975 – 2018 Freunde des Musik Podium Stuttgart e.V. Vorwort Meine Tonaufzeichnungen – auf der Suche nach dem goldenen ist im Gegensatz zur Literatur und Malerei zu können. Denn für mich ist der Unterschied Schnitt zwischen Ausdruckscharakter und technischer Perfektion „flüchtig“, deshalb kann man ihre Ergebnisse zwischen Livekonzert und Studioaufnahme nicht erneut abrufen, überprüfen und festhalten. vergleichbar mit einem gefilmten Livekonzert und einer Filmproduktion. Da geht es nicht Jeder Interpret eines musikalischen Werks ist in dieser Situation der Überprüfung, dass seine Im Lauf der Zeit, vor allem mit dem Beginn nur um die größere Vollkommenheit des Er- damit befasst, gleichzeitig seinen Klang zu emotionale Empfindungswelt eine ganz andere der digitalen Aufzeichnung, hat die sogenannte reichbaren durch die Möglichkeit, in einzelnen entwickeln und diesen in die Architektur des ist als zum Zeitpunkt der Klangentstehung. „Postproduktion“, also die technische Nach- Abschnitten zu denken, sondern vor allem Werkes einzubringen. Er ist also mit dem Augen- Denn um Klänge unmittelbar und vor der bearbeitung von Aufnahmen, erheblich an darum, die verschiedenen Anläufe nachträg- blick der Klangerzeugung ebenso beschäftigt Öffentlichkeit zu erzeugen, erfordert es andere Gewicht gewonnen. Was wären a cappella- lich unter die Lupe zu nehmen und den goldenen wie er die Form des Werkes vom ersten Ton Voraussetzungen und eine andere Einstel- Aufnahmen ohne die Möglichkeit des „pitch- Schnitt zwischen Ausdruckscharakter und tech- an voraussehen muss. Zu einem kontrollieren- lung zu ihnen, als wenn sie mit der nötigen shifts“ (Tonhöhenveränderung), was wäre ein nischer Vollkommenheit aus der gewonnenen den Nachhören der gestalteten Klänge kann Distanz abgehört werden – zumal mit der optimales Gleichgewicht von Chor und Orches- Distanz zu finden. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

New Head for Hawford, OV Artists, Stephen Cleobury Concert & A

N ew Head for Hawford, OV Artists, Stephen Cleobury concert & a tribute to Cecil Duckworth Announcement of New Head at King’s Hawford The Headmaster and Governors of The King’s School, Worcester are delighted to announce the appointment of Mrs Jennie Phillips as the new Head of King’s Hawford, one of Worcester’s leading 2 – 11 Prep Schools. Jennie will join in April 2021 from Monmouth School Girls’ Prep School where she is currently the Head. She was appointed from a dynamic field of sitting Heads and Deputies, and was the unanimous choice of the Headmaster, Governors and the staff who met her. Jennie was educated at Oxford High School, and read Education at the University of Exeter. A keen hiker and swimmer, Jennie is married to Eddie and they have two daughters, Amelia and Daisy, who are all excited about the move. Reflecting on her appointment, Mrs Phillips said, “I am absolutely delighted to be joining the team at King’s Hawford. The school has a wonderful warmth and a sense of community which is clearly held dear by parents, staff and pupils alike. I very much look forward to getting to know the school community and building on the excellent work of Mr Jim Turner, whilst working closely with Mr Richard Chapman, Head of King’s St Albans, under the Head of our Foundation, Mr Gareth Doodes. We will work together to provide parents with the choice of two outstanding, vibrant Prep school learning environments with high aspirations, that prepare our pupils well for the next step in their journey as they move on to King’s Worcester at the age 11.” The Headmaster of the King’s Foundation, Gareth Doodes, celebrated Jennie’s appointment. -

Tianjin Juilliard Faculty Concert

The Tianjin Juilliard School presents Tianjin Juilliard Faculty Concert Monday, February 25, 2019, 7:00pm Cosmos Hall SAINT-SAËNS Fantaisie for Violin and Harp, Op. 124 GLINKA Romance for Violin, Cello, and Harp MOZART Oboe Quartet in F Major, K. 370/368b Intermission BRAHMS Piano Quintet, Op. 34 I. Allegro non troppo II. Andante, un poco Adagio III. Scherzo. Allegro IV. Finale. Poco sostenuto-Allegro non troppo Program order and selections are subject to change. Changes will be announced from the stage. Learn more about The Tianjin Juilliard School by visiting our website: tianjin.juilliard.edu About the Artists Scott Bell Oboist Scott Bell has performed recitals as part of the Music in a Great Space series in Pittsburgh and Reykjavik, Iceland. He has also appeared with the Santa Fe Opera, Glimmerglass Opera, Atlanta Symphony, National Symphony, Minnesota Orchestra, and Milwaukee Symphony. He is a member of the critically acclaimed Pittsburgh Reed Trio. As well as having been a member of the two-time Grammy Award winning Pittsburgh Symphony since 1993, Bell also holds the Mr. and Mrs. William Rinehart endowed oboe chair. Bell has been on the faculties of Northern Illinois University, Tulane University, Trinity College, Wesleyan University, Carnegie Mellon University, and Duquesne University. He attended the Cleveland Institute of Music as a student of legendary oboist and pedagogue John Mack. In 1982, Bell became the first oboist to win First Prize at the prestigious Fernand Gillet Competition. Sheila Browne Recently named William Primrose Memorial Recitalist Sheila Browne has performed across six continents. She premiered a concerto written for her by Kenneth Jacobs at the international viola congresses in Australia and South Africa and recorded it with the Kiev Philharmonic. -

Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CATALOGUE 2018 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany CEO: Jan Mojto Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

Promoting Interdisciplinarity: Its Purpose and Practice in Arts Programming Shannon Farrow Mcneely

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar English, Linguistics, and Communication College of Arts and Sciences 2018 Promoting Interdisciplinarity: Its Purpose and Practice in Arts Programming Shannon Farrow McNeely Denise Gillman Danielle Hartman University of Mary Washington, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/elc Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Higher Education Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Farrow McNeely, Shannon, Denise Gillman, and Danielle Hartman. “Promoting Interdisciplinarity: Its Purpose and Practice in Arts Programming.” Journal of Performing Arts Leadership in Higher Education IX (2018): 55–67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in English, Linguistics, and Communication by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Performing Arts Leadership in Higher Education Volume IX Fall 2018 Laurence Kaptain, co-editor Mark Reimer, co-editor ISSN 2151-2744 (online) ISSN 2157-6874 (print) Christopher Newport University Newport News, Va. Te Journal of Performing Arts Leadership in Higher Education is a recognized academic journal published by Christopher Newport University, a public liberal arts institution in Newport News, Virginia. Copyright to each published article is owned jointly by the Rector and Visitors of Christopher Newport University and the author(s) of the article. 2 Editorial Board (Fall 2018 through Spring 2021) Seth Beckman, Duquesne University Robert Blocker, Yale University Robert Cutietta, University of Southern California Nick Erickson, Louisiana State University John W.