Developmental Disproportions on Polish Lands in the 19Th and 20Th C. (Prior to 1939)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memory As Politics: Narratives of Communism and the Shape of a Community

Memory as Politics: Narratives of Communism and the Shape of a Community by Katarzyna Korycki A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Katarzyna Korycki 2017 Memory as Poltics: Narratives of Communism and the Shape of a Community Katarzyna Korycki Doctor of Philosophy Department of Poltical Science University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This work traces how the past is politicized in post-transition spaces, how it enters the political language, and what effects it produces. Expanding the framework of collective memory literature and anchoring the story in Poland, I argue that the narratives of past communism structure political competition and affect the present-day imaginary of common belonging - that is, they determine political positions of players and they reveal who is included in and excluded from the conception of the ‘we.’ First, I develop the concept of mnemonic capital - a politically productive symbolic resource that accrues to political players based on their turn to, and judgment of, the past - and demonstrate how the distribution of that capital results in sharply differentiated political identities. (I identify four positions generalizable to other post-transition settings.) Second, I trace how narratives of the past constitute the boundary of the ‘we’. I find that in their approaches and judgments of communism, the current political elites conflate communism and Jewishness. In doing so, they elevate the nation and narrow its meaning to ascriptive, religion-inflected, ethnicity. Third, I argue that the field of politics and the field of belonging interact and do not simply exist on parallel planes. -

Niektóre Aspekty Procesów Narodotwórczych NA Polesiu W Dwudziestoleciu Międzywojennym W Świetle Badań Terenowych Józefa Obrębskiego

SPRAWY NARODOWOŚCIOWE Seria nowa / NATIONALITIES AFFAIRS New series, 51/2019 DOI: 10.11649/sn.1894 Article No. 1894 PAvEL AbLAmSkI NIEkTóRE ASPEkTy PROcESów NAROdOTwóRczych NA POLESIu w dwudzIESTOLEcIu mIędzywOjENNym w śwIETLE bAdAń TERENOwych józEFA ObRębSkIEgO SOmE ASPEcTS OF NATION-FORmINg PROcESSES IN POLESIE IN ThE INTERwAR PERIOd IN ThE LIghT OF FIELd STudIES OF józEF ObRębSkI A b s t r a c t The article presents the problem of shaping national identity in the Polesie voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic in the light of ethnosociological research by Józef Obrębski. The JózEf ObRębSkI researcher’s theses were confronted with sources created ETNOSOCJOLOgIA by three entities that both registered and directly influenced POLESIE WCzORAJ I DzIŚ the nationalization process of the Polesie population. They included state administration, national movements (Ukrainian and, to a lesser extent, belarusian and Russian), and the com- ............................... munist movement. from the moment of arrival in Polesie, Obrębski’s expedition clashed with the brutal principles of na- PAVEL AbLAMSkI Instytut Historii im. Tadeusza Manteuffla Polskiej tionality policy implemented by the voivode Wacław kostek- Akademii Nauk, Warszawa biernacki. Due to the significant difficulties in field work, the E-mail: [email protected] theses regarding the problem under consideration are some- https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4455-8770 times hidden between the lines, but they are devoid of shades CITATION: Ablamski, P. (2019). of conformism. The quoted source material positively verifies Niektóre aspekty procesów narodotwórczych na Polesiu w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym Obrębski’s field observations regarding the intensity and terri- w świetle badań terenowych Józefa Obrębskiego. torial scope of the process of nationalization of the Poleshuks Sprawy Narodowościowe. -

SAPARD REVIEW in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania

SAPARD REVIEW in Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Poland and Romania IMPACT ANALYSIS OF THE AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT APRIL 2005 SAPARD REVIEW 2 COMPARATIVE STUDY ON THE SAPARD PROGRAMME - SEVEN POINTS OF VIEW SAPARD REVIEW IN BULGARIA, CZECH REPUBLIC, ESTONIA, HUNGARY, LATVIA, POLAND AND ROMANIA Impact analysis of the agriculture and rural development REPORT ON THE EFFECTIVENESS AND RELEVANCY OF INVESTMENT ACTIVITIES UNDER SAPARD IN BULGARIA IN ITS ROLE AS A PRE-ACCESSION FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE INSTRUMENT Miroslava Georgieva, Director of "Rural Development and Investments" Directorate Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Bulgaria NATIONAL REVIEW ON THE SAPARD PROGRAMME IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC Petra Cerna, IUCN - The International Union for Nature Conservation Regional Office for Europe, European Union Liaison Unit, Belgium SAPARD IN ESTONIA Doris Matteus, chief specialist, Ministry of Agriculture of Estonia, market development bureau, Estonia, www.praxis.ee PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTING THE SAPARD PROGRAMME IN HUNGARY Katalin Kovacs, Researcher Centre for Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Hungary, www.ceu.hu SAPARD IN LATVIA Juris Hazners, Project Manager Agricultural Marketing Promotion Center Latvian State Institute of Agrarian Economics, Latvia NATIONAL REVIEW OF SAPARD PRE-ACCESSION ASSISTANCE IMPACT ON NATIONAL AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN POLAND Tomasz Grosse, Head of the project Institute of Public Affairs, Poland, www.isp.org.pl NATIONAL REVIEW ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SAPARD PROGRAMME -

Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia As Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks

Teresa Smolińska Chair of Culture and Folklore Studies Faculty of Philology University of Opole Researchers of Culture Confronted with the “Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia as Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks Abstract: Considering that in the last few years culinary matters have become a fashionable topic, the author is making a preliminary attempt at assessing many myths and authoritative opinions related to it. With respect to this aim, she has reviewed utilitarian literature, to which culinary handbooks certainly belong (“Con� cerning the studies of comestibles in culture”). In this context, she has singled out cookery books pertaining to only one region, Upper Silesia. This region has a complicated history, being an ethnic borderland, where after the 2nd World War, the local population of Silesians ��ac���������������������uired new neighbours����������������������� repatriates from the ����ast� ern Borderlands annexed by the Soviet Union, settlers from central and southern Poland, as well as former emigrants coming back from the West (“‘The treasures of culinary heritage’ in cookery books from Upper Silesia”). The author discusses several Silesian cookery books which focus only on the specificity of traditional Silesian cuisine, the Silesians’ curious conservatism and attachment to their regional tastes and culinary customs, their preference for some products and dislike of other ones. From the well�provided shelf of Silesian cookery books, she has singled out two recently published, unusual culinary handbooks by the Rev. Father Prof. Andrzej Hanich (Opolszczyzna w wielu smakach. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. 2200 wypróbowanych i polecanych przepisów na przysmaki kuchni domowej, Opole 2012; Smaki polskie i opolskie. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. -

Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza

ISSN 1641–0033 POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO HISTORYCZNE ODDZIAŁ W BIAŁYMSTOKU BIULETYN HISTORII POGRANICZA Nr 14 Białystok 2014 Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza Pismo Oddziału Polskiego Towarzystwa Historycznego w Białymstoku Rada Redakcyjna Adam Dobroński (Białystok),Jan Dzięgielewski (Warszawa), ks. Tadeusz Krahel (Białystok), Algis Kasperavičius (Vilno), Aklvydas Nikžentaitis (Vilno), Aleś Smalianczuk (Grodno-Warszawa) Redakcja Jan Jerzy Milewski – redaktor Aleksander Krawcewicz (Grodno) i Rimantas Miknys (Wilno) – zastępcy redaktora, Marek Kietliński, ks. Tadeusz Kasabuła, Cezary Kuklo, Paweł Niziołek, Anna Pyżewska, Jan Snopko, Wojciech Śleszyński Recenzenci Prof. dr hab. Norbert Kasparek (Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski w Olsztynie) Prof.dr Vladas Sirutavičius (Instytut Historii Litwy w Wilnie) Adres redakcji 15-637 Białystok, ul. Warsztatowa 1a e-mail: [email protected] Libra s.c. xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxx SPIS TREŚCI Artykuły Łukasz Baranowski, Dochody plebanów dekanatu kowieńskiego w końcu XVIII wieku .......................................................................................... 5 Tatiana Woronicz, Prostytucja w Mińsku (druga połowa XIX – początek XX wieku) ... 19 Algis Kasperavičius, Rusofilstwo czy pragmatyzm: Litwini wobec Rosji i Niemiec w latach I wojny światowej .............................................................................. 35 Wital Harmatny, Główne trudności na drodze do ożywienia komasacji w województwie poleskim w latach 1921-1939 ................................................ 45 Autoreferaty Siarhiej -

УДК 339.92 Joanna Grzela, Doctor of Humanities Andrzej Juszczyk, Doctor of History

Теоретичні і практичні аспекти економіки та інтелектуальної власності 2012 Випуск 1, Том 2 УДК 339.92 Joanna Grzela, Doctor of Humanities Andrzej Juszczyk, Doctor of History KIELCE /ŚWIĘTOKRZYSKIE AND VINNYTSA REGIONS – PARTNERSHIP AND COOPERATION FROM PERSPECTIVE PAST DECADES. Гжеля Дж., Ющик А. Партнерська співпраця між м. Кельце (Свентокшинское воєводство) і Вінницьким областю у світлі останніх десятиліть. У статті представлені основні, а також правові основи співпраці, покладеної в 1950 році між Кельце (Свентокшинское воєводство) і Вінницьким регіоном. Незважаючи на перетворення, що проходять в обох країнах, це співпраця як і раніше актуально в умовах нового міжнародного стану. У статті висвітлена низка заходів, практичне застосування яких буде корисне для ряду регіонів, округів, що виявляють цікавість до цієї співпраці. Гжеля Дж., Ющик А. Партнерское сотрудничество между г. Кельце (Свентокшинское воеводство) и Винницкой областью регионом в свете последних десятилетий. В статье представлены основные, а также правовые основы сотрудничества, положенного в 1950 году между Кельце (Свентокшинское воеводство) и Винницким регионом. Несмотря на преобразования, проходящие в обеих странах, это сотрудничество по-прежнему актуально в условиях новой международной обстановки. В статье освещен ряд мероприятий, практическое применение которых будет полезно для ряда регионов, округов, проявляющих интерес к этому сотрудничеству. Grzela J., Juszczyk A. Kielce /Świętokrzyskie and Vinnytsa Regions – Partnership and Cooperation From Perspective Past Decades. The aim of this article is to show the way the cooperation between the two regions has come. It presents the formal and the legal bases of the cooperation. These are both the bases that lay at the heart of the beginning of cooperation in the 1950s and the bases that have been in effect since the time the political transformations occurred in both countries and are still valid in the new international situation. -

Kieleckie Szkolnictwo W Obchodach Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego 1957–1966/67 DOI 10.25951/4234

Almanach Historyczny 2020, t. 22, s. 237–275 Anita Młynarczyk-Tomczyk (Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach) ORCID: 0000-0002-7116-4198 Kieleckie szkolnictwo w obchodach Tysiąclecia Państwa Polskiego 1957–1966/67 DOI 10.25951/4234 Summary Schools in Kielce in the celebration of the Millennium of the Polish State 1957–1966/67 A survey of initiatives in the field of school infrastructure, a package of school and extracurric- ular activities, which on the occasion of the Millennium of the Polish State (1960–1966) were available in the schools of the Kielce voivodeship pointed to their enormous popularity. What was the most recognizable initiative was the program of the construction of schools – Monu- ments of the Millennium of the Polish State. Despite numerous shortcomings of the program (it was commissioned by the authorities, financial contributions were mostly imposed, which ultimately did not bring the expected results), it was undoubtedly very useful. The celebration of the Millennium of the Polish State was also clearly reflected in the didactic and educational work of schools. The programs and handbooks described the millennium of the history of the Polish nation and state, reducing or omitting the participation of the Church. The same objective was fulfilled by additional youth work, which supplemented the content of curricu- lum. In the context of anti-church politics, a lot of effort was put into the proper preparation of teachers, especially young educators, to popularize the millennium in a non-religious spirit. The range of extracurricular activities was the most extensive. Undoubtedly, they had a pos- itive influence on shaping the historical awareness of the young generation. -

Maleniec the Village of Maleniec Upon River Czarna Is Lo- Cated 24 Km West of Końskie. It Occupies an Important Place in the Hi

aleniec The village of Maleniec upon River Czarna is lo- Old Ironworks ter wheel made of cast iron and approximately thirty machine from the Old Mechanical Forge lection of paleontological exhibits including petrified foot-prints of dino- The first records of the forge date cated 24 km west of Końskie. It occupies an important Maleniec 54, 26-242 Ruda Maleniecka, tel. +48 41 373 11 42 mid-18th century and the beginning of the 19th century: turning la- Stara Kuźnica 46, saurs. www.maleniec.powiat.konskie.pl back to the 17th century. The bast furna- 26-205 Nieświń, place in the history of Polish industry. In Maleniec sur- thes, planers, multiradial drilling machines, presses, and 150-year-old En- ce was built in 1860, and it was in opera- tel. +48 41 371 91 87 vivedM a 200-year-old complex of rolling-mill and nail-presses founded glish machine tools saved from many closing down industrial establish- Jan Pazdur Ecomuseum of Natural History and Technology ielpia Wielka is situated some 40 km from Kielce and 10 km tion till 1893. The forge facilities inclu- by by Jacek Jezierski, castellan of Łuków, in 1784. Considered very ments. In addition to those, also hydrotechnical equipment, administra- ul. Wielkopiecowa 1, 27-200 Starachowice from Końskie. The Museum of the Old Polish Industrial Re- de a water supply system, dyke, outlets, tarachowice, tel./ fax +48 41 275 40 83 modern at that time, the plant was visited by king Stanisław August tion building, lodgings for workers and a school building survived. Ano- gion, a branch of the Museum of Technology in Warsaw, is a and two overshot water-wheels. -

Tsikhoratski I P., Il'in A.L..Pdf

ISSN 2410-3810 ТУРИЗМ И ГОСТЕПРИИМСТВО. 2018.№1 УДК 94(438) П. ЦИХОРАЦКИ, доктор хабилитованы, профессор Институт истории Вроцлавский университет, г. Вроцлав, Польша E–mail: [email protected] А.Л. ИЛЬИН, канд. физ.-мат. наук, доцент кафедры высшей математики и ИТ Полесский государственный университет, г. Пинск, Республика Беларусь E–mail: [email protected] Статья поступила 9 апреля 2018г. РАЗВИТИЕ ТУРИЗМА НА ТЕРРИТОРИИ ПОЛЕССКОГО ВОЕВОДСТВА В 30-х ГОДАХ ХХ ВЕКА В настоящей статье рассматривается история развития туризма в Полесском воеводстве в 30- е годы ХХ века, политическое значение развития туризма в деле интеграции Полесья в Польское государство и полонизации местного населения. Особое внимание уделяется Пинску и его окрес- тностям как региону с наибольшим туристическим потенциалом. Ключевые слова: Полесское воеводство, туризм, национальная политика, природа, инфраструк- тура. Сразу после провозглашения независимости Польши в ноябре 1918 года ее руководство пони- мало важное экономическое и культурное значение развития туризма в стране, а также и полити- ческое его значение для интеграции и полонизации восточных кресов (окраин). Так, польский исс- ледователь Малгожата Леван [1, с.47, 48] пишет: «Власти II Речи Посполитой от начала существо- вания государства проявили заинтересованность сферой туризма. В 1919 г. в рамках Министерст- ва публичных работ создан отдел туризма. В 1925 г. были организованы воеводские туристичес- кие комиссии. ВПолесГУ 1932 г. вопросы, связанные с туризмом, были переданы Министерству транспор- та, где создали отдел общего туризма. Более активное вмешательство государства в сферу туризма наступило в 1935 г., когда была создана Лига поддержки туризма (Liga Popieraniu Turystyki). ЛПТ была представительством отдела туризма Министерства транспорта, однако она включала пред- ставителей самоуправления и других заинтересованных министерств». -

Cercosporoid Fungi of Poland Monographiae Botanicae 105 Official Publication of the Polish Botanical Society

Monographiae Botanicae 105 Urszula Świderska-Burek Cercosporoid fungi of Poland Monographiae Botanicae 105 Official publication of the Polish Botanical Society Urszula Świderska-Burek Cercosporoid fungi of Poland Wrocław 2015 Editor-in-Chief of the series Zygmunt Kącki, University of Wrocław, Poland Honorary Editor-in-Chief Krystyna Czyżewska, University of Łódź, Poland Chairman of the Editorial Council Jacek Herbich, University of Gdańsk, Poland Editorial Council Gian Pietro Giusso del Galdo, University of Catania, Italy Jan Holeksa, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland Czesław Hołdyński, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland Bogdan Jackowiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland Stefania Loster, Jagiellonian University, Poland Zbigniew Mirek, Polish Academy of Sciences, Cracow, Poland Valentina Neshataeva, Russian Botanical Society St. Petersburg, Russian Federation Vilém Pavlů, Grassland Research Station in Liberec, Czech Republic Agnieszka Anna Popiela, University of Szczecin, Poland Waldemar Żukowski, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland Editorial Secretary Marta Czarniecka, University of Wrocław, Poland Managing/Production Editor Piotr Otręba, Polish Botanical Society, Poland Deputy Managing Editor Mateusz Labudda, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Reviewers of the volume Uwe Braun, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Germany Tomasz Majewski, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Editorial office University of Wrocław Institute of Environmental Biology, Department of Botany Kanonia 6/8, 50-328 Wrocław, Poland tel.: +48 71 375 4084 email: [email protected] e-ISSN: 2392-2923 e-ISBN: 978-83-86292-52-3 p-ISSN: 0077-0655 p-ISBN: 978-83-86292-53-0 DOI: 10.5586/mb.2015.001 © The Author(s) 2015. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, provided that the original work is properly cited. -

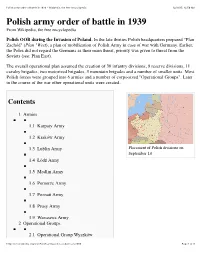

Polish Army Order of Battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM Polish Army Order of Battle in 1939 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Polish army order of battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM Polish army order of battle in 1939 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Polish OOB during the Invasion of Poland. In the late thirties Polish headquarters prepared "Plan Zachód" (Plan "West), a plan of mobilization of Polish Army in case of war with Germany. Earlier, the Poles did not regard the Germans as their main threat, priority was given to threat from the Soviets (see: Plan East). The overall operational plan assumed the creation of 30 infantry divisions, 9 reserve divisions, 11 cavalry brigades, two motorized brigades, 3 mountain brigades and a number of smaller units. Most Polish forces were grouped into 6 armies and a number of corps-sized "Operational Groups". Later in the course of the war other operational units were created. Contents 1 Armies 1.1 Karpaty Army 1.2 Kraków Army 1.3 Lublin Army Placement of Polish divisions on September 1st 1.4 Łódź Army 1.5 Modlin Army 1.6 Pomorze Army 1.7 Poznań Army 1.8 Prusy Army 1.9 Warszawa Army 2 Operational Groups 2.1 Operational Group Wyszków https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_army_order_of_battle_in_1939 Page 1 of 9 Polish army order of battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM 2.2 Independent Operational Group Narew 2.3 Independent Operational Group Polesie 3 Supporting forces 4 See also Armies Karpaty Army Placement of divisions on September 1, 1939 Created on July 11, 1939, under Major General Kazimierz Fabrycy. Armia Karpaty was created after Germany annexed Czechoslovakia and created a puppet state of Slovakia. -

1 a Polish American's Christmas in Poland

POLISH AMERICAN JOURNAL • DECEMBER 2013 www.polamjournal.com 1 DECEMBER 2013 • VOL. 102, NO. 12 $2.00 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY SUPERMODEL ESTABLISHED 1911 www.polamjournal.com JOANNA KRUPA JOURNAL VISITS DAR SERCA DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE PAGE 12 RORATY — AN ANCIENT POLISH CUSTOM IN HONOR OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN • MUSHROOM PICKING, ANYONE? MEMORIES OF CHRISTMAS 1970 • A KASHUB CHRISTMAS • NPR’S “WAIT, WAIT … ” APOLOGIZES FOR POLISH JOKE CHRISTMAS CAKES AND COOKIES • BELINSKY AND FIDRYCH: GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN • DNA AND YOUR GENEALOGY NEWSMARK AMERICAN SOLDIER HONORED BY POLAND. On Nov., 12, Staff Sergeant Michael H. Ollis of Staten Island, was posthumously honored with the “Afghanistan Star” awarded by the President of the Republic of Poland and Dr. Thaddeus Gromada “Army Gold Medal” awarded by Poland’s Minister of De- fense, for his heroic and selfl ess actions in the line of duty. on Christmas among The ceremony took place at the Consulate General of the Polish Highlanders the Republic of Poland in New York. Ryszard Schnepf, Ambassador of the Republic of Po- r. Thaddeus Gromada is professor land to the United States and Brigadier General Jarosław emeritus of history at New Jersey City Universi- Stróżyk, Poland’s Defense, Military, Naval and Air Atta- ty, and former executive director and president ché, presented the decorations to the family of Ollis, who of the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of DAmerica in New York. He earned his master’s and shielded Polish offi cer, Second lieutenant Karol Cierpica, from a suicide bomber in Afghanistan.