Acta 109.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niektóre Aspekty Procesów Narodotwórczych NA Polesiu W Dwudziestoleciu Międzywojennym W Świetle Badań Terenowych Józefa Obrębskiego

SPRAWY NARODOWOŚCIOWE Seria nowa / NATIONALITIES AFFAIRS New series, 51/2019 DOI: 10.11649/sn.1894 Article No. 1894 PAvEL AbLAmSkI NIEkTóRE ASPEkTy PROcESów NAROdOTwóRczych NA POLESIu w dwudzIESTOLEcIu mIędzywOjENNym w śwIETLE bAdAń TERENOwych józEFA ObRębSkIEgO SOmE ASPEcTS OF NATION-FORmINg PROcESSES IN POLESIE IN ThE INTERwAR PERIOd IN ThE LIghT OF FIELd STudIES OF józEF ObRębSkI A b s t r a c t The article presents the problem of shaping national identity in the Polesie voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic in the light of ethnosociological research by Józef Obrębski. The JózEf ObRębSkI researcher’s theses were confronted with sources created ETNOSOCJOLOgIA by three entities that both registered and directly influenced POLESIE WCzORAJ I DzIŚ the nationalization process of the Polesie population. They included state administration, national movements (Ukrainian and, to a lesser extent, belarusian and Russian), and the com- ............................... munist movement. from the moment of arrival in Polesie, Obrębski’s expedition clashed with the brutal principles of na- PAVEL AbLAMSkI Instytut Historii im. Tadeusza Manteuffla Polskiej tionality policy implemented by the voivode Wacław kostek- Akademii Nauk, Warszawa biernacki. Due to the significant difficulties in field work, the E-mail: [email protected] theses regarding the problem under consideration are some- https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4455-8770 times hidden between the lines, but they are devoid of shades CITATION: Ablamski, P. (2019). of conformism. The quoted source material positively verifies Niektóre aspekty procesów narodotwórczych na Polesiu w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym Obrębski’s field observations regarding the intensity and terri- w świetle badań terenowych Józefa Obrębskiego. torial scope of the process of nationalization of the Poleshuks Sprawy Narodowościowe. -

Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza

ISSN 1641–0033 POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO HISTORYCZNE ODDZIAŁ W BIAŁYMSTOKU BIULETYN HISTORII POGRANICZA Nr 14 Białystok 2014 Biuletyn Historii Pogranicza Pismo Oddziału Polskiego Towarzystwa Historycznego w Białymstoku Rada Redakcyjna Adam Dobroński (Białystok),Jan Dzięgielewski (Warszawa), ks. Tadeusz Krahel (Białystok), Algis Kasperavičius (Vilno), Aklvydas Nikžentaitis (Vilno), Aleś Smalianczuk (Grodno-Warszawa) Redakcja Jan Jerzy Milewski – redaktor Aleksander Krawcewicz (Grodno) i Rimantas Miknys (Wilno) – zastępcy redaktora, Marek Kietliński, ks. Tadeusz Kasabuła, Cezary Kuklo, Paweł Niziołek, Anna Pyżewska, Jan Snopko, Wojciech Śleszyński Recenzenci Prof. dr hab. Norbert Kasparek (Uniwersytet Warmińsko-Mazurski w Olsztynie) Prof.dr Vladas Sirutavičius (Instytut Historii Litwy w Wilnie) Adres redakcji 15-637 Białystok, ul. Warsztatowa 1a e-mail: [email protected] Libra s.c. xxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxx SPIS TREŚCI Artykuły Łukasz Baranowski, Dochody plebanów dekanatu kowieńskiego w końcu XVIII wieku .......................................................................................... 5 Tatiana Woronicz, Prostytucja w Mińsku (druga połowa XIX – początek XX wieku) ... 19 Algis Kasperavičius, Rusofilstwo czy pragmatyzm: Litwini wobec Rosji i Niemiec w latach I wojny światowej .............................................................................. 35 Wital Harmatny, Główne trudności na drodze do ożywienia komasacji w województwie poleskim w latach 1921-1939 ................................................ 45 Autoreferaty Siarhiej -

Tsikhoratski I P., Il'in A.L..Pdf

ISSN 2410-3810 ТУРИЗМ И ГОСТЕПРИИМСТВО. 2018.№1 УДК 94(438) П. ЦИХОРАЦКИ, доктор хабилитованы, профессор Институт истории Вроцлавский университет, г. Вроцлав, Польша E–mail: [email protected] А.Л. ИЛЬИН, канд. физ.-мат. наук, доцент кафедры высшей математики и ИТ Полесский государственный университет, г. Пинск, Республика Беларусь E–mail: [email protected] Статья поступила 9 апреля 2018г. РАЗВИТИЕ ТУРИЗМА НА ТЕРРИТОРИИ ПОЛЕССКОГО ВОЕВОДСТВА В 30-х ГОДАХ ХХ ВЕКА В настоящей статье рассматривается история развития туризма в Полесском воеводстве в 30- е годы ХХ века, политическое значение развития туризма в деле интеграции Полесья в Польское государство и полонизации местного населения. Особое внимание уделяется Пинску и его окрес- тностям как региону с наибольшим туристическим потенциалом. Ключевые слова: Полесское воеводство, туризм, национальная политика, природа, инфраструк- тура. Сразу после провозглашения независимости Польши в ноябре 1918 года ее руководство пони- мало важное экономическое и культурное значение развития туризма в стране, а также и полити- ческое его значение для интеграции и полонизации восточных кресов (окраин). Так, польский исс- ледователь Малгожата Леван [1, с.47, 48] пишет: «Власти II Речи Посполитой от начала существо- вания государства проявили заинтересованность сферой туризма. В 1919 г. в рамках Министерст- ва публичных работ создан отдел туризма. В 1925 г. были организованы воеводские туристичес- кие комиссии. ВПолесГУ 1932 г. вопросы, связанные с туризмом, были переданы Министерству транспор- та, где создали отдел общего туризма. Более активное вмешательство государства в сферу туризма наступило в 1935 г., когда была создана Лига поддержки туризма (Liga Popieraniu Turystyki). ЛПТ была представительством отдела туризма Министерства транспорта, однако она включала пред- ставителей самоуправления и других заинтересованных министерств». -

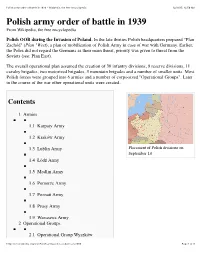

Polish Army Order of Battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM Polish Army Order of Battle in 1939 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Polish army order of battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM Polish army order of battle in 1939 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Polish OOB during the Invasion of Poland. In the late thirties Polish headquarters prepared "Plan Zachód" (Plan "West), a plan of mobilization of Polish Army in case of war with Germany. Earlier, the Poles did not regard the Germans as their main threat, priority was given to threat from the Soviets (see: Plan East). The overall operational plan assumed the creation of 30 infantry divisions, 9 reserve divisions, 11 cavalry brigades, two motorized brigades, 3 mountain brigades and a number of smaller units. Most Polish forces were grouped into 6 armies and a number of corps-sized "Operational Groups". Later in the course of the war other operational units were created. Contents 1 Armies 1.1 Karpaty Army 1.2 Kraków Army 1.3 Lublin Army Placement of Polish divisions on September 1st 1.4 Łódź Army 1.5 Modlin Army 1.6 Pomorze Army 1.7 Poznań Army 1.8 Prusy Army 1.9 Warszawa Army 2 Operational Groups 2.1 Operational Group Wyszków https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_army_order_of_battle_in_1939 Page 1 of 9 Polish army order of battle in 1939 - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 12/18/15, 12:50 AM 2.2 Independent Operational Group Narew 2.3 Independent Operational Group Polesie 3 Supporting forces 4 See also Armies Karpaty Army Placement of divisions on September 1, 1939 Created on July 11, 1939, under Major General Kazimierz Fabrycy. Armia Karpaty was created after Germany annexed Czechoslovakia and created a puppet state of Slovakia. -

Kinantropologie

ČESKÁ 2018, vol. 22, no. 2 KINANTROPOLOGIE Časopis České kinantropologické společnosti vychází s finanční podporou AV ČR, ČOV, FTVS UK Praha, FTK UP Olomouc a FSpS Brno. Journal of the Czech kinanthropological society is published with financial support of AV CR, COV, FTVS UK Prague, FTK UP Olomouc a FSpS Brno. Česká kinantropologie Česká kinantropologie (ISSN 1211-9261) (ISSN 1211-9261) vydává Česká kinantropologická společnost. published 4x annually Vychází 4x ročně. by Czech Kinanthropology Association. Časopis Česká kinantropologie je recenzovaný Journal Česká kinantropologie is reviewed scholarly vědecký časopis zaměřený na kinantropologii. journal that focuses on kinanthropology. It publishes Publikuje příspěvky o výsledcích výzkumu z oblasti papers about results of theoretical, empirical teorie, empirického výzkumu a metodologie. Cílem je and methodological research. The objective is to podporovat rozvoj vědeckého poznání záměrné endorse scientific development of the intentional pohybové činnosti, její struktury a funkcí a jejích physical movement, its structure and functions vztahů k rozvoji člověka jako biopsychosociálního as well as its connections to development of men individua. as bio-psycho-sociological entity. Nabídka rukopisů Manuscript submission Redakce přijímá původní výzkumné práce, teoretické The editors accept original empirical research papers, studie, přehledové studie, stručné zprávy z odborných theoretical studies, short news about conferences and akcí (konference, semináře apod.), recenze nových workshops, reviews -

Boris N. Florja (Hg.), Belorussija I Ukraina. Istorija I Kul't

Zitierhinweis von Scheliha, Wolfram: Rezension über: Boris N. Florja (Hg.), Belorussija i Ukraina. Istorija i kul’tura. 5: Sbornik stat’ej, Moskva: Inslav RAN, 2015, in: Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas / jgo.e-reviews, jgo.e-reviews 2018, 2, S. 24-27, https://www.recensio.net/r/f704513ef8634e99927cdd7a989234d2 First published: Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas / jgo.e-reviews, jgo.e-reviews 2018, 2 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. jgo.e-reviews 8 (2018), 2 24 grundlegend umzudenken. Die vorgeschlagene, aus der Naturwissenschaft entlehnte, Metapher hier von einer Breccie zu sprechen, wo trotz ‚Verbackung’ der einzelnen Elemente zu einem neuen Ganzen letztere doch unterscheidbar bleiben, kann man durchaus einiges abgewinnen. Es lädt zumindest zum Nachdenken über imperiale Inklusionskonzeptionen (bzw. deren Weiterwirken, etwa am Beispiel innerstädtischer Phantomgrenzen) ein. Trotz der heterogenen Ansätze im Einzelnen und den verständlichen methodischen wie analytischen Schwierigkeiten des angestrebten raumzeitlichen Vergleichs ist hier ein ansehnlicher Beitrag zur Diskussion von Phantomgrenzen und der sozialen Raumproduktion gelungen. Bezeichnend für alle Beiträge ist dabei nicht allein der Versuch, entlang eines gemeinsamen Forschungskonzeptes zu arbeiten, um dadurch die vorhandenen Theorien (erfolgreich) zu präzisieren. Vielmehr liegt ein zentraler Zugang zu den behandelten Themen in der den Autorinnen und Autoren jeweils eigenen Sozialisierung begründet. Erst eine bewusst genutzte Zwei- oder Mehrsprachigkeit erlauben es, solchen Phänomenen, die oftmals nur auf sehr subtile Weise in der Gesellschaft aufzuspüren sind, nachzustellen und sie für eine weitere wissenschaftliche Diskussion sichtbar zu machen. -

The Determination of Nationality in Selected European Countries up to 1938 OPEN ACCESS

The Determination of Nationality in Selected European Countries up to 1938 OPEN ACCESS Dan Gawrecki KEY WORDS: European History — Nationalism — Cisleithania — Ethnicity The topic of this study1 was chosen in the knowledge that the assessment and evalu- ation of census practices in Cisleithania and in post-1918 Czechoslovakia2 necessar- ily requires comparison at least with practices in neighbouring countries. The deter- mination of respondents’ nationality was always associated with various polemics which became part of the political struggle, and the census data was frequently called into doubt. Here I attempt to summarize various opinions on the relevance and cred- ibility of census practices — opinions expressed by journalists and historiographers, both at the time of the censuses and also at a later date. Attention will primarily be fo- cused on Germany and Poland — firstly due to the sizeable German and Polish minor- ities in the Czechoslovak Republic, and secondly because the main criterion for na- tionality in these two countries was language; nationality was generally not equated with citizenship of a state. The findings presented here are based on statistical data, supported by other sources and numerous scholarly studies of the subject. I trace how the concept of nationality gradually shifted under specific historical conditions, and I observe the changing criteria that were used as a basis for the determination of nationality from the time of the first censuses to contemporary approaches and evaluations. Only marginal attention is paid to the evaluation of Czechoslovak cen- sus practices in foreign literature; this is dealt with only in cases when it forms part of the wider general or comparative context. -

Public Health in the East Voivodeships of the Second Polish Republic

ARCHIWUM HISTORII I FILOZOFII MEDYCYNY 2011, 74, 85-90 EVGENIJ TISHCHENKO Public Health in the East Voivodeships of the Second Polish Republic Zdrowie publiczne na wschodzie województw II Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej Uniwersytet Medyczny w Grodnie,Wydział Lekarsko-Diagnostyczny, Katedra Zdrowia Publicznego Streszczenie Summary Artykuł opisuje stan zdrowia publicznego we wschodnich The article describes the state of public health in the województwach Polski w okresie międzywojennym. Wska eastern voevodeships of the Second Polish Republic; re zuje na wpływ warunków życia na stan zdrowia publicz veals the impact of life conditions on public health. The nego. Omawia znaczenie chorób zakaźnych i społecznych, author points out spread of infectious and social diseases; sposoby zapobiegania im oraz aktywność instytucji me covers activities on their prevention and decrease; char dycznych. acterizes activities of established medical institutions. Słowa kluczowe: zdrowie publiczne, wschodnia Polska, Keywords: public health, eastern voevodeships, the Sec okres międzywojenny w Polsce ond Polish Republic West Belarus belonged to the Second Polish Repub such department of Nowogródek Voivodeship Director lic (proclaimed on November 11, 1918) pursuant to ate comprised the head — a doctor (G. Hrzhanovski, the Treaty of Riga (between Russia and Poland, 1921). 1921-1927; Z. Domanski, 1927-1930; E. Machiulevich, The administrative-territorial division, accepted in 1930-1933; L. Blakhushevski, 1933-1936; A. Zhurakovski, Poland, was established there: -

The Book of the Righteous of the Eastern Borderlands 1939−1945

THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 About the Ukrainians who rescued Poles subjected to extermination by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army Edited by Romuald Niedzielko THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 THE BOOK OF THE RIGHTEOUS OF THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS 1939−1945 About the Ukrainians who rescued Poles subjected to extermination by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army Edited by Romuald Niedzielko Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation Graphic design Krzysztof Findziński Translation by Jerzy Giebułtowski Front cover photograph: Ukrainian and Polish inhabitants of the Twerdynie village in Volhynia. In the summer of 1943 some local Ukrainians were murdering their Polish neigh- bors while other Ukrainians provided help to the oppressed. Vasyl Klishchuk – one of the perpetrators, second from the right in the top row. Stanisława Dzikowska – lying on ground in a white scarf, one of the victims, murdered on July 12, 1943 with her parents and brothers (photo made available by Józef Dzikowski – Stanisława’s brother; reprinted with the consent of Władysław and Ewa Siemaszko from their book Ludobójstwo dokonane przez nacjonalistów ukraińskich na ludności polskiej Wołynia 1939–1945, vol. 1–2 [Warsaw, 2000]) Copyright by Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ISBN 978-83-7629-461-2 Visit our website at www.ipn.gov.pl/en and our online bookstore at www.ipn.poczytaj.pl. CONTENTS Introduction . 7 1 Volhynia Voivodeship . 23 2 Polesie Voivodeship . -

100 Lat Samorz<0105>

3DWURQDWKRQRURZ\ Adam Struzik (ZD0DOLQRZVND*UXSLęVND 0DUV]DãHN ²3U]HZRGQLF]ĈFD5DG\ :RMHZyG]WZD PVW:DUV]DZ\ 0D]RZLHFNLHJR prof. dr hab. Jacek Majchrowski 3UH]\GHQW.UDNRZD $QGU]HM3ãRQND 3UH]HV=DU]ĈGX=33 Organizatorzy 0X]HXP1LHSRGOHJãRĤFLZ:DUV]DZLHMHVWMHGQRVWNĈRUJDQL]DF\MQĈ 6DPRU]ĈGX:RMHZyG]WZD0D]RZLHFNLHJR 6$025=ć' ,QVW\WXW+LVWRULL 8QLZHUV\WHWX-DJLHOORęVNLHJR MECENASEM Patronat medialny 678/(&,(6$025=ć'8 KULTURY 678/(&,(6$025=ć'8 Partnerzy Stulecie samorządu pod redakcją naukową Janusza Mierzwy i Tadeusza Skoczka Warszawa 2019 RECENZENT Romuald Turkowski REDAKTOR TECHNICZNY Marzena Milewska Muzeum Niepodległości w Warszawie jest jednostką organizacyjną Samorządu Województwa Mazowieckiego MUZEUM NIEPODLEGŁOŚCI W WARSZAWIE al. Solidarności 62, 00-240 Warszawa, tel. 22 826 90 91 e-mail: [email protected] www.muzeumniepodleglosci.pl ISBN 978-83-65438-84-0 PRZYGOTOWANIE DO DRUKU FALL ul. Garczyńskiego 2, 31–524 Kraków www.fall.pl ISBN 978-83-66027-49-7 Nakład 200 egz. SPIS TRECI Wstęp . 5 MACIEJ WOJTACKI Ewolucja pozycji prawnoustrojowej samorządu terytorialnego w procesie zmian konstytucyjnych w II Rzeczypospolitej w świetle obecnego stanu badań Evolution of the legal and political position of a local government in the pro- cess of constitutional changes in the Second Republic of Poland in the light of the current state of research. 9 ARKADIUSZ INDRASZCZYK Samorząd w myśli politycznej ruchu ludowego. Refl eksje w stulecie samorządu w niepodległej Polsce Local government in the political thought of the people’s movement. Refl ec- tions on the 100th anniversary of self-government in independent Poland. 31 PIOTR CICHORACKI Czynnik polityczny w wyborach samorządowych na Polesiu (1926–1939) Political factor in local government elections in Polesie (1926–1939) . -

Issues of Land Reform and Poland's Post-War Borders in The

Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej ■ LI-SI(2) Adrian Karolak MBP Łódź-Widzew Issues of land reform and Poland’s post-war borders in the broadcasts of Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station Outline of contents: Between 1941 and 1942, one general radio station, and 16 secret for- eign-language (national) stations operated from Soviet territory; among them was the Polish- -language Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station, which began operations in August 1941, and functioned until 22 August 1944. According to the broadcasters, the land reform should consist in expropriating the owners of large landholdings, and distributing their possessions among peasants and farm labourers. As regards the Poland’s future borders, the broadcasters presented the position of their political superiors, according to whom the eastern voivodeships of the Polish Republic should be transferred to the Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian Soviet Republics. Keywords: Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station, Communist International (Comintern), Polish communists, Polish post-war borders, land reform During its three-year existence, the Tadeusz Kościuszko Radio Station addressed many subjects relevant to Polish citizens who found themselves under German occupation. Among the key issues discussed, two merit special attention: the land reform and Poland’s post-war borders. The main idea behind the planned socio-economic changes was, according to the Polish left, the need to cut ties with a bygone reality, strange to the “simple” man (peasants and workers). This can be concluded from the station’s broadcasts. Their authors claimed that the relations of property prevailing in the Polish countryside in the interwar period were incompatible with the needs of the peasants. -

Architecture of Brest-On-The-Bug in the Second Polish Republic

ARCHITECTURE OF BREST-ON-THE-BUG IN THE SECOND POLISH REPUBLIC MICHA PSZCZÓ KOWSKI Architecture of the Second Polish Republic has In the period of the First Polish Republic, Brest been widely exploring for some years. Yet, when it was a city of great importance due to its central comes to the Borderland cities, there is still much to location. The signi [ cance was huge as the city was discover. Even if we take into account only voivode- situated on the border of Polish, Lithuanian and ship cities, it is no more than Lvov that is relatively Ruthenian lands (Fig. 1). In 1569, as a result of well portrayed 1; to some extent also Vilnius 2 and new administrative division pursuant to the Union Stanyslaviv 3. Other voivodeship cities, not to men- of Lublin, strong in terms of politics and culture tion district towns, have not been the subject of Brest became the capital of the Brest-Lithuanian interest of Polish architecture historians. This is the voivodeship and perfomed this function till the par- consequence of a small number of source materials. titions. Unfortunately, no trace of this ancient past In the most in \ uential interwar architectural bulle- has been left. In 1831, according to the decision tin ‘Architektura i Budownictwo’ (‘Architecture and of Russian authorities, the city was almost com- Construction’) Borderland architecture appeared pletely destroyed and one of the largest fortresses very rarely. In the scope of interest of the maga- in the world appeared in its place. A few kilome- zine were mainly Warsaw and the centre of Poland.