Census Report of Patiala State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics of Genocide

I THE BACKGROUND 2 1 WHY PUNJAB? Exit British, Enter Congress In 1849 the Sikh empire fell to the British army; it was the last of their conquests. Nearly a hundred years later when the British were about to relinquish India they were negotiating with three parties; namely the Congress Party largely supported by Hindus, the Muslim League representing the Muslims and the Akali Dal representing the Sikhs. Before 1849, the Satluj was the boundary between the kingdom of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and other Sikh states, such as Patiala (the largest and most influential), Nabha and Jind, Kapurthala, Faridkot, Kulcheter, Kalsia, Buria, Malerkotla (a Muslim state under Sikh protection). Territory under Sikh rulers stretched from the Peshawar to the Jamuna. Those below the Satluj were known as the Cis-Satluj states. 3 In these pre-independence negotiations, the Akalis, led by Master Tara Singh, represented the Sikhs residing in the territory which had once been Ranjit Singh’s kingdom; Yadavindra Singh, Maharaja of Patiala, spoke for the Cis- Satluj states. Because the Sikh population was thinly dispersed all over these areas, the Sikhs felt it was not possible to carve out an entirely separate Sikh state and had allied themselves with the Congress whose policy proclaimed its commitment to the concept of unilingual states with a federal structure and assured the Sikhs that “no future Constitution would be acceptable to the Congress that did not give full satisfaction to the Sikhs.” Gandhi supplemented this assurance by saying: “I ask you to accept my word and the resolution of the Congress that it will not betray a single individual, much less a community .. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

List of Registered Projects in RERA Punjab

List of Registered Real Estate Projects with RERA, Punjab as on 01st October, 2021 S. District Promoter RERA Type of Contact Details of Project Name Project Location Promoter Address No. Name Name Registration No. Project Promoter Amritsar AIPL Housing G T Road, Village Contact No: 95600- SCO (The 232-B, Okhla Industrial and Urban PBRERA-ASR02- Manawala, 84531 1. Amritsar Celebration Commercial Estate, Phase-III, South Infrastructure PC0089 Amritsar-2, Email.ID: Galleria) Delhi, New Delhi-110020 Limited Amritsar [email protected] AIPL Housing Village Manawala, Contact No: 95600- # 232-B, Okhla Industrial and Urban Dream City, PBRERA-ASR03- NH1, GT Road, 84531 2. Amritsar Residential Estate, Phase-III, South Infrastructure Amritsar - Phase 1 PR0498 Amritsar-2, Email.ID: Delhi, New Delhi-110020 Limited Punjab- 143109 [email protected] Golf View Corporate Contact No: 9915197877 Alpha Corp Village Vallah, Towers, Sector 42, Golf Model Industrial PBRERA-ASR03- Email.ID: Info@alpha- 3. Amritsar Development Mixed Mehta Link Road, Course Road, Gurugram- Park PM0143 corp.com Private Limited Amritsar, Punjab 122002 M/s. Ansal Buildwell Ltd., Village Jandiala Regd. Off: 118, Upper Contact No. 98113- Guru Ansal Buildwell Ansal City- PBRERA-ASR02- First Floor, 62681 4. Amritsar Residential (Meharbanpura) Ltd Amritsar PR0239 Prakash Deep Building, Email- Tehsil and District 7, Tolstoy Marg, New [email protected] Amritsar Delhi-110001 Contact No. 97184- 07818 606, 6th Floor, Indra Ansal Housing PBRERA-ASR02- Verka and Vallah Email Id: 5. Amritsar Ansal Town Residential Prakash, 21, Barakhamba Limited PR0104 Village, Amritsar. ashok.sharma2@ansals. Road, New Delhi-110001 com Page 1 of 220 List of Registered Real Estate Projects with RERA, Punjab as on 01st October, 2021 S. -

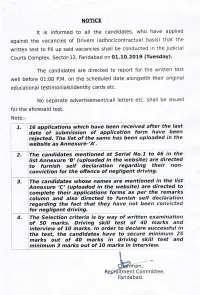

DRIVER LIST and NOTICE for WRITTEN EXAMINATION.Pdf

COMBINE Annexure-A Reject List of applications for the post of Driver August -2019 ( Ad-hoc) as received after due date 20/08/19 Date of Name of Receipt No. Father's / Husband Name Address of the candidate Contact No. Date of Birth Remarks Receipt Candidate Vill-Manesar, P.O Garth Rotmal Application 1 08/21/19 Yogesh Kumar Narender Kumar Teh- Ateli Distt Mohinder Garh 10/29/93 Received after State Haryana 20.08.2019 Khor PO Ateli Mandi Teh Ateli, Application 2 08/21/19 Pankaj Suresh Kumar 9818215697 12/20/93 Received after distt mahendergarh 20.08.2019 Amarjeet S/O Krishan Kumar Application 3 08/21/19 Amarjeet Kirshan Kumar 05/07/92 Received after VPO Bhikewala Teh Narwana 20.08.2019 121, OFFICER Colony Azad Application 4 08/21/19 Bhal Singh Bharat Singh nagar Rajgarh Raod, Near 08/14/96 Received after Godara Petrol Pump Hissar 20.08.2019 Vill Hasan, Teh- Tosham Post- Application 5 08/21/19 Rakesh Dharampal 10/15/97 Received after Rodhan (Bhiwani) 20.08.2019 VPO Jonaicha Khurd, Teh Application 6 08/21/19 Prem Shankar Roshan Lal Neemarana, dist Alwar 12/30/97 Received after (Rajasthan) 20.08.2019 VPO- Bhikhewala Teh Narwana Application 7 08/21/19 Himmat Krishan Kumar 09/05/95 Received after Dist Jind 20.08.2019 vill parsakabas po nagal lakha Application 8 08/21/19 Durgesh Kumar SHIMBHU DAYAL 09/05/95 Received after teh bansur dist alwar 20.08.2019 RZC-68 Nihar Vihar, Nangloi New Application 9 08/26/19 Amarjeet Singh Mohinder Singh 03/17/92 Received after Delhi 20.08.2019 Vill Palwali P.O Kheri Kalan Sec- Application 10 08/26/19 Rohit Sharma -

(OH) Category 1 14 Muhammad Sahib Town- Malerkotla, Distt

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Beldar, Mali, Mali-cum-Chowkidar, Mali -cum-Beldar- cum-Chowkidar and Road Gang Beldar reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, No. No. and Father’s Name OH etc. Sarv Shri/ Smt./ Miss %age of disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 14 Muhammad Sahib Town- Malerkotla, Distt. 01.10.1998 OH 50% S/o Muhammad Shafi Sangrur 2 54 Harjinder Singh S/o Vill. Kalia, W.No.1, 10.11.1993 OH 55% Gurmail Singh Chotian, Teh. Lehra, Distt. Sangrur, Punjab. 3 61 Aamir S/o Hameed W.No.2, Muhalla Julahian 08.11.1993 OH 90% Wala, Jamalpura, Malerkotla, Sangrur 4 63 Hansa Singh S/o Vill. Makror Sahib, P.O. 15.10.1982 OH 60% Sham Singh Rampura Gujjran, Teh. Moonak, Distt. Sangrur, Punjab. 5 65 Gurjant Singh S/o Vill. Kal Banjara, PO Bhutal 02.09.1985 OH 50% Teja Singh Kalan, Teh. Lehra, Distt. Sangrur 6 66 Pardeep Singh S/o VPO Tibba, Teh. Dhuri, 15.04.1986 OH 60% Sukhdev Singh Distt. Sangrur 7 79 Gurmeet Singh S/o # 185, W. No. 03, Sunam, 09.07.1980 OH 60% Roshan Singh Sangrur, Punjab. 8 101 Kamaljit Singh S/o H. No.13-B, Janta Nagar, 09.08.1982 OH 90% Sh. Charan Singh Teh. Dhuri, Distt. -

Contact Detail of Blos to Be Provided by Eros District No

Contact Detail of BLOs to be provided by EROs District No. & Name: Department/ AC No. Part No. Name Designation Mobile No Organisation 103-Barnala 1 Amrik Singh ETT TEACHER GPS Bhadalwad 98152-38466 GHS 103-Barnala 2 Sukhwinder Singh ETT TEACHER 80545-00510 BHADALWAD GHS 103-Barnala 3 Vikas Goyal DPE TEACHER 94171-24090 BHADALWAD 103-Barnala 4 MegRaj SLA GSSS HAMIDI 98768-21820 GPS 103-Barnala 5 Rana Singh ETT TEACHER 98721-20907 KARAMGARH AGRICULTURE 103-Barnala 6 Karminder Singh A/R 99140-07490 KARAMGARH COMPUTER G.H SCHOOL 103-Barnala 7 Gurmit Singh 98156-91500 TEACHER KARAMGARH 103-Barnala 8 Jaskaran Singh CLERK GPS THULEWAL 80541-28938 103-Barnala 9 Baldev Singh ETT TEACHER GPS NANGAL 88727-99638 103-Barnala 10 Ramandeep Singh ETT TEACHER GPS THELIWAL 99146-23001 103-Barnala 11 Gurgeet Singh ETT TEACHER GPS THELEWAL 94174-52488 103-Barnala 12 Jagseer Singh ETT TEACHER GPS JHALUR 97801-94294 103-Barnala 13 Sukhpal Singh ETT TEACHER GPS JHALUR 99156-53156 103-Barnala 14 Dilpreet Singh ART & CRAFT GSSS JHALOOR 98143-80049 103-Barnala 15 Pargat Singh ETT TEACHER GPS KATTU 98880-28683 MARKET 103-Barnala 16 Gulzar Singh GA 98761-46343 COMMITTEE 103-Barnala 17 Ranjit Singh ETT TEACHER GPS SEKHA 97810-22384 103-Barnala 18 Baljeet Singh ETT TEACHER GPS SANGHERA 86997-40100 103-Barnala 19 Amarjit Singh PTI GSS SEKHA 98031-52942 GPS SANDHU 103-Barnala 20 Jagrant Singh ETT TEACHER 95010-17066 PATTI HS SCHOOL 103-Barnala 21 Mandeep Sharma CLERK 95012-93700 KARAMGARH BURAJ 103-Barnala 22 Chamkaur Singh ETT TEACHER 95010-19060 FATEHGARH 103-Barnala -

Download PDF (733

This PDF was generated on 20/12/2016 from online resources as part of the Qatar Digital Library's digital archive. The online record contains extra information, high resolution zoomable views and transcriptions. It can be viewed at: http://www.qdl.qa/en/archive/81055/vdc_100023494119.0x000001 Reference Photo 430/78 Title Curzon Collection: 'Coronation Durbar, Delhi, 1903. Of His Majesty King Edward VII. Viceroy. Baron Curzon of Kedleston, P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E.' (Crookshank) Date(s) 1903 (CE, Gregorian) Written in English in Latin Extent and Format 1 red full-leather, published album (207 pages) containing 133 photographic lightly tipped onto album pages with letterpress captions preceding. Holding Institution British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers Copyright for document Public Domain About this record Imprint: The Coronation Durbar, Delhi, 1903 (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1903) Genre/Subject Matter: The volume is a specially published edition, under the imprint of Bourne and Shepherd and printed by Eyre & Spottiswoode, London. The title page and four page introduction are followed by prints lightly tipped onto the album pages, each preceded by a sheet of letterpress caption. The volume provides a comprehensive record of the events and personalities involved in the Durbar, summed up in the introduction as follows: 'The Delhi Durbar Photo Biographic Album is designed as a pictorial rather than a historical record of the Coronation Durbar. The photographs which it is composed of have been chosen from an immense collection of portraits and views far beyond the compass of any single volume. The pictures here given represent the important visitors, Princes, delegates, functions, etc., and constitute the most perfect and complete reproduction in photography of an Imperial celebration which will live in the minds of men as the greatest of its kind in the history of the modern world.' The album presents a particularly fine series of portraits of Indian princes who attended the Durbar. -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Changing Geography of Himachal Pradesh Jagdish Chand1 Assistant Professor, Dept

ISSN: 2319-8753 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (An ISO 3297: 2007 Certified Organization) Vol. 2, Issue 11, November 2013 Changing Geography of Himachal Pradesh Jagdish Chand1 Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geography, Govt. PG College, Nahan, HP, India1 Abstract: Administrative geography of Himachal Pradesh has been a saga of several territorial surgeries and shuffling. This hill state has a colonial past and since its formation on April 15th, 1948 it has undergone a number of administrative readjustments and alterations. This process has been of merger of new areas and realignment of internal boundaries. This resulted into gradual increase in the geographical area of the state along with changing territorial expressions. The entire course of administrative realignment was not an arbitrary or spontaneous process but it was interplay of various cultural, politico-historical and geographical factors. In the present study, administrative history of Himachal Pradesh since 1872 to 2001 has been examined from a geographical perspective using administrative maps of different time periods prepared by Census of India. This study is primarily focused on changing nature of administrative boundaries in Himachal Pradesh. Keywords: Administrative, Hill, Politico-historical, Himachal Pradesh. I. INTRODUCTION The evidences of human occupancies in the Himalayan region can be traced back to two million years ago. As the time passed, primitive human groups organized themselves into tribal republics, which were called janapadas in Sanskrit literature. These were both a state and a cultural unit. There is a reference in the Mahabharata about four famous janapadas existing at that time in the Himalayas namely Audambara, Trigarta, Kuluta and Kunindas (Singh, 1997) [7]. -

Heritage Walk Booklet

Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || (Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful.) A quotation from the 5th Guru, Sri Guru Arjan Dev, describing the city of Ramdaspur (Amritsar) in Guru Granth Sahib, on Page No. 1362. It is engraved on north façade of the Town hall, the starting point of Heritage Walk. • Heritage Walk starts from Town Hall at 8:00 a.m. and ends at Entrance to - The Golden Temple 10:00 a.m. everyday • Summer Timing (March to November) - 0800hrs • Winter Timing (December to February) - 0900hrs Evening: 1800 hrs to 2000 hrs (Summer) 1600 hrs to 1800 hrs (Winter) • Heritage Walk contribution: Rs. 25/- for Indian Rs. 75/- for Foreigner • For further information: Tourist Information Centre, Exit Gate of The Amritsar Railway Station, Tel: 0183-402452 M.R.P. Rs. 50/- Published by: Punjab Heritage and Tourism Promotion Board Archives Bhawan, Plot 3, Sector 38-A, Chandigarh 160036 Tel.: 0172-2625950 Fax: 0172-2625953 Email: [email protected] www.punjabtourism.gov.in Ddithae Sabhae Thhaav Nehee Thudhh Jaehiaa || I have seen all places, but none can compare to You. Badhhohu Purakh Bidhhaathai Thaan Thoo Sohiaa || The Primal Lord, the Architect of Destiny, has established You; thus You are adorned and embellished. Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || (Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful.) It is engraved on north façade of the Town hall, the starting point of the Heritage Walk. Vasadhee Saghan Apaar Anoop Raamadhaas Pur || Ramdaspur is prosperous and thickly populated, and incomparably beautiful. Harihaan Naanak Kasamal Jaahi Naaeiai Raamadhaas Sar ||10|| O Lord! Bathing in the Sacred Pool of Ramdas, the sins are washed away, O Nanak. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :URBAN STATE : JAMMU & KASHMIR DISTRICT : Anantnag Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 DEPARTMENT OF ANIMAL HUSBANDRY NAZ BASTI ANTNTNAG OPPOSITE TO SADDAR POLICE STATION ANANTNAG PIN CODE: 2000 10 - 50 192102, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 ASSTSTANT SERICULTURE OFFICER NAGDANDY , PIN CODE: 192201, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 1985 10 - 50 3 INTENSIVE POULTRY PROJECT MATTAN DTSTT. ANANTNAG , PIN CODE: 192125, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: 1988 10 - 50 NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0140-Agricultural and animal husbandry service activities, except veterinary activities. 4 DEPTT, OF HORTICULTURE KULGAM TEH KULGAM DISTT. ANANTNAG KASHMIR , PIN CODE: 192231, STD CODE: NA , 1969 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 5 DEPTT, OF AGRICULTURE KULGAM ANANTNAG NEAR AND BUS STAND KULGAM , PIN CODE: 192231, STD CODE: NA , 1970 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0200-Forestry, logging and related service activities 6 SADU NAGDANDI PIJNAN , PIN CODE: 192201, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : 1960 10 - 50 N.A. 7 CONSERVATOR LIDDER FOREST CONSERVATOR LIDDER FOREST DIVISION GORIWAN BIJEHARA PIN CODE: 192124, STD CODE: 1970 10 - 50 DIVISION NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A.