Joseph Blake Page Music Editor: Joseph Blake Healing & Health: Making a Wild Salad, by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. -

I. Early Days Through 1960S A. Tezuka I. Series 1. Sunday A

I. Early days through 1960s a. Tezuka i. Series 1. Sunday a. Dr. Thrill (1959) b. Zero Man (1959) c. Captain Ken (1960-61) d. Shiroi Pilot (1961-62) e. Brave Dan (1962) f. Akuma no Oto (1963) g. The Amazing 3 (1965-66) h. The Vampires (1966-67) i. Dororo (1967-68) 2. Magazine a. W3 / The Amazing 3 (1965) i. Only six chapters ii. Assistants 1. Shotaro Ishinomori a. Sunday i. Tonkatsu-chan (1959) ii. Dynamic 3 (1959) iii. Kakedaze Dash (1960) iv. Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (1966-68 / 68-72) v. Blue Zone (1968) vi. Yami no Kaze (1969) b. Magazine i. Cyborg 009 (1966, Shotaro Ishinomori) 1. 2nd series 2. Fujiko Fujio a. Penname of duo i. Hiroshi Fujimoto (Fujiko F. Fujio) ii. Moto Abiko (Fujiko Fujio A) b. Series i. Fujiko F. Fujio 1. Paaman (1967) 2. 21-emon (1968-69) 3. Ume-boshi no Denka (1969) ii. Fujiko Fujio A 1. Ninja Hattori-kun (1964-68) iii. Duo 1. Obake no Q-taro (1964-66) 3. Fujio Akatsuka a. Osomatsu-kun (1962-69) [Sunday] b. Mou Retsu Atarou (1967-70) [Sunday] c. Tensai Bakabon (1969-70) [Magazine] d. Akatsuka Gag Shotaiseki (1969-70) [Jump] b. Magazine i. Tetsuya Chiba 1. Chikai no Makyu (1961-62, Kazuya Fukumoto [story] / Chiba [art]) 2. Ashita no Joe (1968-72, Ikki Kajiwara [story] / Chiba [art]) ii. Former rental magazine artists 1. Sanpei Shirato, best known for Legend of Kamui 2. Takao Saito, best known for Golgo 13 3. Shigeru Mizuki a. GeGeGe no Kitaro (1959) c. Other notable mangaka i. -

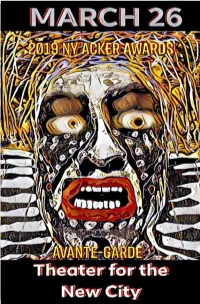

NY ACKER Awards Is Taken from an Archaic Dutch Word Meaning a Noticeable Movement in a Stream

1 THE NYC ACKER AWARDS CREATOR & PRODUCER CLAYTON PATTERSON This is our 6th successful year of the ACKER Awards. The meaning of ACKER in the NY ACKER Awards is taken from an archaic Dutch word meaning a noticeable movement in a stream. The stream is the mainstream and the noticeable movement is the avant grade. By documenting my community, on an almost daily base, I have come to understand that gentrification is much more than the changing face of real estate and forced population migrations. The influence of gen- trification can be seen in where we live and work, how we shop, bank, communicate, travel, law enforcement, doctor visits, etc. We will look back and realize that the impact of gentrification on our society is as powerful a force as the industrial revolution was. I witness the demise and obliteration of just about all of the recogniz- able parts of my community, including so much of our history. I be- lieve if we do not save our own history, then who will. The NY ACKERS are one part of a much larger vision and ambition. A vision and ambition that is not about me but it is about community. Our community. Our history. The history of the Individuals, the Outsid- ers, the Outlaws, the Misfits, the Radicals, the Visionaries, the Dream- ers, the contributors, those who provided spaces and venues which allowed creativity to flourish, wrote about, talked about, inspired, mentored the creative spirit, and those who gave much, but have not been, for whatever reason, recognized by the mainstream. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

The Dispute Over Barefoot Gen (Hadashi No Gen) and Its Implications in Japan

International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 5, No. 11, November 2015 The Dispute over Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen) and Its Implications in Japan Mizuno Norihito “closed shelf” handling of the comic was disputed from Abstract—Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen) is a comic series, various points of view. Second, the educational the central theme of which is the author Nakazawa Keiji’s appropriateness of the comic in a school library collection experiences as an atomic survivor in Hiroshima during and and its value as educational material were discussed. Third, after World War II, which became the subject of disputes in the the author Nakazawa‟s view of history, especially of summer and fall of 2013 in Japan. The Board of Education of the City of Matsue requested that all the elementary and junior Japanese wartime conduct and the issue of war responsibility high schools in the city move the comic books to closed shelves as revealed in the volumes simultaneously became an issue in to restrict students’ free access in December 2012, citing an dispute. excess of violent description as the reason. A local newspaper The dispute over Barefoot Gen is thus another episode of report about the education board’s request published in August historical controversy (rekishi ninshiki mondai). The 2013 received broader attention from the major Japanese historical controversy is today known to be one of the causes media and ignited disputes between journalists, critics and of discord between Japan and its East Asian neighbors. The scholars, who engaged in arguments over two issues. Along with the propriety of the “closed shelf” request, the comic work’s best example is the controversy over Japanese history attitude to Japanese wartime conduct became an issue in textbooks that has sporadically flared up since the early dispute. -

Barefoot Gen School Edition Vol 5 Pdf Free Download

BAREFOOT GEN SCHOOL EDITION VOL 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keiji Nakazawa | 266 pages | 01 Jul 2018 | Last Gasp,U.S. | 9780867198355 | English | San Francisco, United States Barefoot Gen School Edition Vol 5 PDF Book The authors are all specialists on their subjects, and in addition to analyzing Japan's pop culture they give the reader a direct taste through the presentation of story plots, character profiles, song lyrics, manga comics samples, photographs and other visuals, as well as the thoughts and words of Japan pop's artists, creators and fans. Originally a journalist he has determined his last act will be to publish a book telling the truth about the Atom Bombing of Hiroshima. Mersis No: Related Searches. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Striking new design with special sturdy Volume 5 follows Gen's struggles in postwar Japan, with massive food shortages and horrendous health problems. The art defuses, not dilutes, the terrible facts and scenes of the tragedy and its aftermath. An all-new, unabridged translation of Keiji Nakazawa's account of the Hiroshima bombing and its aftermath, drawn from his own experiences. Crumb, cartoonist, Gen effectively bears witness to one of the entral horrors of our time. With the money they hope to go into the countryside and buy rice but they have to sneak it past police checkpoints that confiscate black market food being smuggled into the city. Striking new design with special sturdy binding. Starting a few months before that event, the ten-volume saga shows life in J Barefoot Gen serves as a reminder of the suffering war brings to innocent people, and as a unique documentation of an especially horrible source of suffering, the atomic bomb. -

Centro Universitario Europeo Per I Beni Culturali Ravello

Centro Universitario Europeo per i Beni Culturali Ravello Territori della Cultura Rivista on line Numero 4 Anno 2011 Iscrizione al Tribunale della Stampa di Roma n. 344 del 05/08/2010 Centro Universitario Europeo per i Beni Culturali Sommario Ravello Comitato di redazione 5 La nuova sfida di RAVELLO LAB 6 Alfonso Andria Beni Culturali e conflitti armati 8 Pietro Graziani Conoscenza del patrimonio culturale Maria Rita Sanzi Di Mino Il sacro e l’ambiente 12 nel mondo antico Claudio La Rocca Lo scavo archeologico 16 di Piazza Epiro a Roma Lina Sabino Maiori (SA), Complesso Abbaziale 20 di Santa Maria de Olearia Roger Lefèvre L’enseignement des sciences 26 du patrimoine culturel dans un monde en changement: une Conférence à Varsovie et un Cours à Ravello en 2011 28 Massimo Pistacchi Storia della fonografia Cultura come fattore di sviluppo Stefania Chirico, Giuseppe Pennisi Strategie gestionali per la valorizzazione delle risorse culturali: 38 il caso di Ravenna Teresa Gagliardi Costruire in Costiera Amalfitana: 54 ieri, oggi e domani? Fabio Pollice, Giulia Urso Le città come fucine culturali. Per una lettura critica delle politiche 64 di rigenerazione urbana Sandro Polci Cult economy: un nuovo/antico driver 72 per i territori minori Metodi e strumenti del patrimonio culturale Maurizio Apicella From the Garden of the Hesperides 84 to the Amalfi Coast. The culture of lemons Matilde Romito Artiste straniere a Positano 90 fra gli anni Venti e gli anni Sessanta Luciana Bordoni Tecnologie 106 e valori culturali Antonio Gisolfi La risoluzione del labirinto 112 Simone Bozzato Territorio, formazione scolastica e innovazione. Attuazione, nella provincia Copyright 2010 © Centro Universitario di Salerno, di un modello applicativo 116 Europeo per i Beni Culturali finalizzato a ridurre il digital divide Territori della Cultura è una testata iscritta al Tribunale della Stampa di Roma. -

Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: the Hiroshima Legacy

Volume 6 | Issue 1 | Article ID 2638 | Jan 01, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Barefoot Gen, The Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy Nakazawa Keiji Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, Translated by Richard H. Minear Click here for Japanese original. See below for video of Barefoot Gen In August 2007 I asked Nakazawa Keiji, manga artist and author ofBarefoot Gen, for an interview. Nakazawa was a first grader when Nakazawa Keiji on August 6, 1945 he experienced the atomic A Father’s Influence bombing. In 1968 he published his first work on the atomic bombing—Struck by Black Rain Asai: Would you speak about your father’s [Kuroi ame ni utarete]—and since then, he has strong influence on the formation of your own appealed to the public with many works on the thinking? atomic bombing. His masterpiece isBarefoot Gen, in which Gen is a stand-in for Nakazawa Nakazawa: Dad’s influence on the formation of himself. His works fromBarefoot Gen on my thinking was strong. Time and again he’d convey much bitter anger and sharp criticism grab me —I was still in first grade—and say, toward a postwar Japanese politics that has “This war is wrong” or “Japan’s absolutely never sought to affix responsibility on those going to lose; what condition will Japan be in who carried out the dropping of the atomic when you’re older? The time will surely come bomb and the aggressive war (the U.S. that when you’ll be able to eat your fill of white rice dropped the atomic bomb, and the emperor and and soba.” At a time when we had only locusts Japan’s wartime leaders who prosecuted the and sweet potato vines to eat, we couldn’t reckless war that incurred the dropping of the imagine that we’d ever see such a wonderful atomic bomb). -

The Comic Artist As a Post-War Popular Critic of Imperial Japan

STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY Department of Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies The Comic Artist as a Post-war Popular Critic of Japanese Imperialism An Analysis of Nakazawa Keiji’s Hadashi no Gen Bachelor Thesis in Japanese Studies Spring Term 2015 Annika Bell Thesis Advisor: Misuzu Shimotori 1 Table of Contents Conventions ......................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ...................................................................... 4 Objectives and Research Question ....................................... 4 2. Background ....................................................................... 5 2.1 History of Imperial Japan ................................................... 5 2.2 Characteristics of Japanese Imperialism ..................... 8 2.3 Role of Popular Culture in Japan .................................. 10 2.4 Hadashi no Gen ..................................................................... 11 3. Material and Methodology ........................................ 14 4. Analysis and Results .................................................... 15 4.1 Imperial Japan in Hadashi no Gen ................................ 15 4.2 Hadashi no Gen and Norakuro ........................................ 19 4.3 Statistics ................................................................................. 22 5. Conclusion ..................................................................... 23 6. Summary ....................................................................... 24 7. Bibliography -

Title Format Released Abyssinians, the Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin

Title Format Released Abyssinians, The Satta Dub CD 1998 Acklin, Barbara The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 2) CD 2002 The Brunswick Anthology (Disc 1) CD 2002 Adams Johnny Johnny Adams Sings Doc Pomus: The Real Me CD 1991 Adams, Johnny I Won't Cry CD 1991 Walking On A Tightrope - The Songs Of Percy Mayfield CD 1989 Good Morning Heartache CD 1993 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Ade, King Sunny Odu CD 1998 Alabama Feels So Right CD 1981 Alexander, Arthur Lonely Just Like Me CD 1993 Allison, DeAnn Tumbleweed CD 2000 Allman Brothers Band, The Beginnings CD 1971 American Song-poem Anthology, The Do You Know The Difference Between Big Wood And Brush CD 2003 Animals, The Animals - Greatest Hits CD 1983 The E.P. Collection CD 1964 Aorta Aorta CD 1968 Astronauts, The Down The Line/ Travelin' Man CD 1997 Competition Coupe/Astronauts Orbit Kampus CD 1997 Rarities CD 1991 Go Go Go /For You From Us CD 1997 Surfin' With The Astronauts/Everything Is A-OK! CD 1997 Austin Lounge Lizards Paint Me on Velvet CD 1993 Average White Band Face To Face - Live CD 1997 Page 1 of 45 Title Format Released Badalamenti, Angelo Blue Velvet CD 1986 Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me CD 1992 Badfinger Day After Day [Live] CD 1990 The Very Best Of Badfinger CD 2000 Baker, Lavern Sings Bessie Smith CD 1988 Ball, Angela Strehli & Lou Ann Barton, Marcia Dreams Come True CD 1990 Ballard, Hank Sexy Ways: The Best of Hank Ballard & The Midnighters CD 1993 Band, The The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down: The Best Of The Band [Live] CD 1992 Rock Of Ages [Disc 1] CD 1990 Music From Big Pink CD 1968 The Band CD 1969 The Last Waltz [Disc 2] CD 1978 The Last Waltz [Disc 1] CD 1978 Rock Of Ages [Disc 2] CD 1990 Barker, Danny Save The Bones CD 1988 Barton, Lou Ann Read My Lips CD 1989 Baugh, Phil 64/65 Live Wire! CD 1965 Beach Boys, The Today! / Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) CD 1990 Concert/Live In London [Bonus Track] [Live] CD 1990 Pet Sounds [Bonus Tracks] CD 1990 Merry Christmas From The Beach Boys CD 2000 Beatles, The Past Masters, Vol.