Media Coverage: Help Or Hinderance in Conflict Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: White, Dean (2012) The UK's Response to the Rwandan Genocide of 1994. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/10122/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html THE UK’S RESPONSE TO THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE OF 1994 DEAN JAMES WHITE PhD 2012 THE UK’S RESPONSE TO THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE OF 1994 DEAN JAMES WHITE MA, BA (HONS) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Research undertaken in the School of Arts and Social Sciences. July 2012 ABSTRACT Former Prime Minister Tony Blair described the UK’s response to the Rwandan genocide as “We knew. -

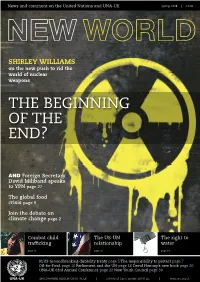

New World Spring 2008.Pdf

news and comment on the United nations and UnA-UK Spring 2008 | £3.00 NE W WORLD SHIRLEY WILLIAMS on the new push to rid the world of nuclear weapons The Beginning of The end? AND Foreign Secretary David Miliband speaks to YPN page 27 The global food crisis page 9 Join the debate on climate change page 2 Combat child The US-Un The right to trafficking relationship water page 16 page 10 page 14 PLUS groundbreaking disability treaty page 5 The responsibility to protect page 7 oil-for-food page 10 Parliament and the Un page 18 david hannay’s new book page 20 UnA-UK 63rd Annual Conference page 22 new Youth Council page 30 UNA-UK UNITED NATIONS ASSOCIATION OF THE UK | 3 Whitehall Court, London SW1A 2EL | www.una.org.uk UNA-UK What is the role of the United Nations in finding solutions to climate change and building CLIMATE CHANGE resilience to its impacts? CONFERENCE SERIES Is the UK government doing enough to build 2008-09 a low-carbon economy? What can you do as an individual ? An upcoming series of one-day conferences on climate change, to be held by UNA-UK in 2008-2009 in different cities around the UK, will be tackling these questions. The first conference of the series will be held in Birmingham on Saturday, 7 June 2008. The second will be held in Belfast on Thursday, 6 November 2008. Two further events are being planned for the autumn of 2008 and early 2009 – one in Wales and the other in Scotland. -

Lead IG for Overseas Contingency Operations

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION INHERENT RESOLVE REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS OCTOBER 1, 2016‒DECEMBER 31, 2016 LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations will coordinate among the Inspectors General specified under the law to: • develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over all aspects of the contingency operation • ensure independent and effective oversight of all programs and operations of the federal government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations • promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse • perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements • report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to publish the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly report on Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR). This is our eighth quarterly report on the overseas contingency operation (OCO), discharging our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. OIR is dedicated to countering the terrorist threat posed by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Iraq, Syria, the region, and the broader international community. The U.S. -

The Kosovo Report

THE KOSOVO REPORT CONFLICT v INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE v LESSONS LEARNED v THE INDEPENDENT INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION ON KOSOVO 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford Executive Summary • 1 It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, Address by former President Nelson Mandela • 14 and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Map of Kosovo • 18 Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Introduction • 19 Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw PART I: WHAT HAPPENED? with associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Preface • 29 Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the uk and in certain other countries 1. The Origins of the Kosovo Crisis • 33 Published in the United States 2. Internal Armed Conflict: February 1998–March 1999 •67 by Oxford University Press Inc., New York 3. International War Supervenes: March 1999–June 1999 • 85 © Oxford University Press 2000 4. Kosovo under United Nations Rule • 99 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) PART II: ANALYSIS First published 2000 5. The Diplomatic Dimension • 131 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, 6. International Law and Humanitarian Intervention • 163 without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, 7. Humanitarian Organizations and the Role of Media • 201 or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Papers from the Conference on Homeland Protection

“. to insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence . .” PAPERS FROM THE CONFERENCE ON HOMELAND PROTECTION Edited by Max G. Manwaring October 2000 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave., Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications and Production Office by calling commercial (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or via the Internet at [email protected] ***** Most 1993, 1994, and all later Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http://carlisle-www.army. mil/usassi/welcome.htm ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. ISBN 1-58487-036-2 ii CONTENTS Foreword ........................ v Overview Max G. Manwaring ............... 1 1. A Strategic Perspective on U. S. Homeland Defense: Problem and Response John J. -

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone

Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone Abou Binneh-Kamara This is a digitised version of a dissertation submitted to the University of Bedfordshire. It is available to view only. This item is subject to copyright. Media Reporting of War Crimes Trials and Civil Society Responses in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone By Abou Bhakarr M. Binneh-Kamara A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. January, 2015 ABSTRACT This study, which seeks to contribute to the shared-body of knowledge on media and war crimes jurisprudence, gauges the impact of the media’s coverage of the Civil Defence Forces (CDF) and Charles Taylor trials conducted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) on the functionality of civil society organizations (CSOs) in promoting transitional (post-conflict) justice and democratic legitimacy in Sierra Leone. The media’s impact is gauged by contextualizing the stimulus-response paradigm in the behavioral sciences. Thus, media contents are rationalized as stimuli and the perceptions of CSOs’ representatives on the media’s coverage of the trials are deemed to be their responses. The study adopts contents (framing) and discourse analyses and semi-structured interviews to analyse the publications of the selected media (For Di People, Standard Times and Awoko) in Sierra Leone. The responses to such contents are theoretically explained with the aid of the structured interpretative and post-modernistic response approaches to media contents. And, methodologically, CSOs’ representatives’ responses to the media’s contents are elicited by ethnographic surveys (group discussions) conducted across the country. -

MR NIK GOWING Main Presenter BBC World, British Broadcasting Corporation, United Kingdom

MR NIK GOWING Main Presenter BBC World, British Broadcasting Corporation, United Kingdom Since February 1996, Nik Gowing has been the main presenter on BBC World News, the BBC’s 24-hour international television news and information channel. He also fronts the channel’s flagship hour-long news programme World News Today. From 1996 to March 2000, Nik was principal anchor for weekday news programme The World Today, and its predecessor, NewsDesk. He was a founding presenter of Europe Direct and has been a guest anchor on both HARDtalk and Simpson’s World. He is also a regular moderator of the Sunday news analysis programme Dateline London. Nik has been a main anchor for much of BBC World News coverage of major international crises including Kosovo in 1999, and the Iraq war in 2003. Nik was on air for six hours shortly after the Twin Towers were hit in New York City on 11 September 2001 and fronted coverage of the unfolding drama of Diana, Princess of Wales’ accident and made the announcement of her death to a global audience estimated at half a billion. He also anchors special location coverage of major international events, and chairs World Debates at the World Economic Forum in Davos and the annual Nobel Awards in Stockholm. Before joining the BBC, Nik was a foreign affairs specialist and presenter at ITN for 18 years. From 1989 to 1996 he was diplomatic editor Channel 4 News, from ITN in London. His reporting from Bosnia was part of the Channel 4 News portfolio, which won the Bafta Best News Coverage award in 1996. -

War Reporting in the International Press: a Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009

War Reporting in the International Press: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009 Dissertation Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Hamburg zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg Mohammedwesam Amer Hamburg, June 2015 War Reporting in the International Press: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Gaza War of 2008-2009 Evaluators 1. Prof. Dr. Jannis Androutsopoulos 2. Prof. Dr. Irene Neverla 3. Prof. Dr. Kathrin Fahlenbrach Date of Oral Defence: 30.10.2015 Declaration • I hereby declare and certify that I am the author of this study which is submitted to the University of Hamburg in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. • This is my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. • This original work or part of it has not been submitted to any other institution or university for a degree. Mohammedwesam Amer June 2015 I Abstract This study analyses the representation of social actors in reports on the Gaza war of 2008-09 in four international newspapers: The Guardian , The Times London , The New York Times and The Washington Post . The study draws on three analytical frameworks from the area of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) models: the transitivity model by Halliday (1985/1994), the socio- semantic inventory by Van Leeuwen (1996), and the classification of quotation patterns by Richardson (2007). The sample of this study consists of all headlines (146) of the relevant news stories and a non-random sample of (40) news stories and (7) editorials. -

Letter N° 3, December 17, 2020

1 France Genocide Tutsi Database https://francegenocidetutsi.org Information Letter n° 3, December 17, 2020 The database official address Nuit et brouillard sur The United States did https://francegenocidetutsi.org le Rwanda not support the RPF (noted below FGT) is a website which brings together documents On March 22, 1994, Prudence Bush- about France’s role in the geno- We have gathered thanks to the nell met Kagame to convince him cide of the Tutsi in Rwanda in archives of the L’Humanité newspa- to accept a representation of the 1994 and a search engine at http: per available on the web the articles Coalition for the Defense of Repub- //francegenocidetutsi.fr.A of Jean Chatain written during his lic (CDR). He refuses, arguing that backup can be accessed at http: two trips to Rwanda in the area lib- they are “criminals, gangsters, they //francegenocidetutsi.ddns.net erated by the Patriotic Front Rwan- threat to kill people”. On March if the official address cannot be dan (RPF) during the genocide. Al- 28, 1994, Ambassador Rawson again reached. Please note that https: though not aware of the country, Jean made pressure for the RPF to accept //francegenocidetutsi.org, http: is one of the few to have under- the CDR. On April 14, 1994, the Sec- //francegenocidetutsi.org, http: stood almost immediately the nature retary of State, Warren Christopher //www.francegenocidetutsi.org of the genocide and the role played is convinced of the will of the Interim are equivalent. by France. While he had published the book Paysages après le génocide Government to secure a ceasefire and (ed. -

Des Journalistes, Dont Sam Kiley, Informent Des Militaires Français Le 26 Juin 1994 De La Poursuite Des Tueries À Bisesero

Des journalistes, dont Sam Kiley, informent des militaires français le 26 juin 1994 de la poursuite des tueries à Bisesero Jacques Morel 30 avril 2017, v0.4 1 La rencontre de Sam Kiley et des militaires français filmée par CNN Figure 1 – Sam Kiley montrant un point sur une carte à des militaires français La rencontre de Sam Kiley, journaliste du quotidien britannique The Times avec des militaires français le 26 juin a été filmée par l’équipe CNN de la journaliste Christiane Amanpour. La référence de l’enregistrement de cette émission dans les archives CNN est la suivante : Date : 06/26/1994 Type : PKG Rptr : Christiane Amanpour Tape No : B10726#02 CNN Id : 90318093 Source : CNN Length : 00 :02 :33 :0 Le résumé est ainsi libellé : 01 :03 :55 :26 - Summary : This country known as the land of 1,000 hills. No Desert Shield, no Operation Restore Hope, no armored vehicles or heavy weapons. Instead, here a couple of platoons set off in jeeps to patrol this part of Rwanda, Looking for civilians in need of help. (0 :00) / 1 1 LA RENCONTRE DE SAM KILEY ET DES MILITAIRES FRANÇAIS FILMÉE PAR CNN 2 Ce clip peut être examiné en version “pre-screen” au prix de $150 USD. Sinon son acquisition coûte $3,500 USD. Il est accessible sur http://www.francegenocidetutsi.org/KileyBucquet26juin1994. mp4 Un examen du “pre-screen” de ce clip laisse voir une scène où un homme au crâne rasé et à lunettes, qui pourrait être le journaliste Sam Kiley, montrant sur une carte certains points à des militaires français. -

Learning Uncertainty Date and Time Thursday, Dec 7, 09:30 – 11:00 Location Room Potsdam I/III

Plenary Title OEB Opening Plenary: Learning Uncertainty Date and Time Thursday, Dec 7, 09:30 – 11:00 Location Room Potsdam I/III Plenary Outline Uncertainty is the defining characteristic of our age. Are workplaces, governments and societies prepared for our uncertain future? How should universities, colleges, schools and workplaces adapt? What should employers do now to plan for the flexible workforce they will need in the future? OEB's Opening Plenary session is about acknowledging uncertainty and preparing for it. It shows how transformative education, training and learning can equip businesses, organisations and individuals with the skills to survive and prosper. Format The aim of the Plenary is to create interaction and the atmosphere of a giant conversation, to set the overall tone for the conference. From the get-go the audience will be encouraged by the moderator to be part and explore the themes and elements the 3 speakers raise in their talks via social media. This audience feedback will drive the direction of travel for the session after each talk and during the final part of the session. The proposed timings are: Nik 5 min (welcome and introductions), Aleks 15 min (on “The Tales, They Are a’Changing), Abigail 15 min (on “Clash of revolutions”), Pasi 15 min (on “Myths and Facts about the Future of Schooling”), Q&A with your audience 40 min. Audience Every year, OEB Global attracts over 2,300 participants from more than 90 countries worldwide, making it the most comprehensive annual meeting place for technology- supported learning and training professionals from the corporate, education and public service sectors.