The Ecology of Song Improvisation As Illustrated by North American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Notes from Kankakee Sands

Nature Notes from Kankakee Sands April 2019 © Jeff Timmons Where There’s a Willow, There’s a Way written by Alyssa Nyberg, Restoration Ecologist for The Nature Conservancy’s Kankakee Sands Project I was standing out in a 400-acre wet prairie just north of our Kankakee Sands office, placidly harvesting seeds when I hear the crackling, sizzling Zzzzap! like the sound of an electrical circuit shorting out. With exactly zero electric lines running through that particular prairie, what could have made that sound? Then I noticed a large willow patch… and where there is a willow patch at Kankakee Sands, there may be a sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) singing its electrical sounding song. Sedge wrens are a rare treat to see and hear, because they are a shy and skittish bird. Unlike the chatty, boisterous, easily-viewed house wren, the sedge wren avoids being seen. Even when frightened, the sedge wren will rarely take flight. Instead, it will run on the ground beneath vegetation. It may take flight, but only briefly, before fluttering to the ground to escape notice. The sedge wren is an even more exciting find because it is state endangered in Indiana. Habitat loss and conversion are the main causes of its decline. However, at Kankakee Sands we have many acres of suitable, wet habitat with plenty of willows. And where there are willows, there is a way for the sedge wren to feed, mate, nest and raise young. Thanks to the restored habitat at Kankakee Sands, we get to enjoy its song during the months of April through October each year. -

Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 2006 Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains Rosalind B. Renfrew Vermont Center for Ecostudies Douglas H. Johnson USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Gary R. Lingle Assessment Impact Monitoring Environmental Consulting W. Douglas Robinson Oregon State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Renfrew, Rosalind B.; Johnson, Douglas H.; Lingle, Gary R.; and Robinson, W. Douglas, "Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains" (2006). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 236. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/236 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in PRAIRIE INVADERS: PROCEEDINGS OF THE 20TH NORTH AMERICAN PRAIRIE CONFERENCE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA AT KEARNEY, July 23–26, 2006, edited by Joseph T. Springer and Elaine C. Springer. Kearney, Nebraska : University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2006. Pages 313-324. AVIAN RESPONSE TO MEADOW RESTORATION IN THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS ROSALIND B. RENFREW, Vermont Center for Ecostudies, P.O. Box 420, Norwich, VT 05055, USA DOUGLAS H. JOHNSON, U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA GARY R. LINGLE, Assessment Impact Monitoring Environmental Consulting, 1568 L Road, Minden, NE 68959, USA W. -

Comprehensive Report Species - Cistothorus Platensis Page I of 19

Comprehensive Report Species - Cistothorus platensis Page I of 19 NatureServe () EXPLORER • '•rr•K•;7",,v2' <-~~~ •••'F"'< •j • ':'•k• N :;}• <"• Seach bot. the Dat -Abou-U Cot Chana eCrite «<Previous I Next»> Cistothorusplatensis - (Latham, 1790) Google, Sedge Wren Search for Images on Google Spanish Common Names: Chivirin Sabanero, Chercan de las Vegas French Common Names: Troglodyte & bec court Other Common Names: Curruira-do-Campo Unique Identifier: ELEMENTGLOBAL.2.105322 Element Code: ABPBG10010 Informal Taxonomy: Animals, Vertebrates - Birds - Perching Birds Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Animalia Craniata Aves Passeriformes Troglodytidae Cistothorus Genus Size: B - Very small genus (2-5 species) Check this box to expand all report sections: Concept Reference 0 Concept Reference: American Ornithologists' Union (AOU). 1998. Check-list of North American birds. Seventh edition. American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC. 829 pp. Concept Reference Code: B98AOU01NAUS Name Used in Concept Reference: Cistothorusplatensis Taxonomic Comments: Formerly known as Short-billed Marsh-Wren. Composed of three groups: STELLARIS (Sedge Wren), PLATENSIS (Western Grass-Wren), and POLYGLOTTUS (Eastern Grass-Wren) (AOU 1998). Constitutes a superspecies with C. MERIDAE and C. APOLINARI (AOU 1998). Conservation Status 0 NatureServe Status Global Status: G5 Global Status Last Reviewed: 03Dec1996 Global Status Last Changed: 03Dec1996 Rounded Global Status: G5 - Secure Nation: United States National Status: N4B,N5N Nation: Canada National Status:N5B -

Sedge Wren, Cistothorus Platensis

Sedge wren, Cistothorus platensis Status: State: Endangered Federal: Migratory Nongame Bird of Management Concern Identification Formerly known as the “short-billed marsh wren,” the sedge wren is a small brown songbird with dark brown vertical streaking on the crown and back. The wings, rump, and tail are brown with dark horizontal barring. The underparts and undertail coverts are buffy. The bill is short, thin, and slightly decurved, and there is an inconspicuous pale eye stripe. Sexes are similar in plumage, although males are slightly larger than © Brian E. Small/ VIREO females. Juveniles resemble adults, but are darker above, buffer below, and have less conspicuous streaking on the head. Like other wrens, the tail is short and often held upwards. The diminutive sedge wren is extremely secretive and is often heard rather than seen. The insect-like song consists of three introductory notes, “tchip, tchip, tchip,” followed by a trill, “tchu, tchu, tchu.” The call note is a “tchip” or “chick.” Habitat Wet meadows, freshwater marshes, bogs, and the drier portions of salt or brackish coastal marshes are home to sedge wrens throughout the year. Along the Delaware Bay shore, sedge wrens may be found in high marsh containing salt-meadow grass (Spartina patens), spike grass (Distichlis spicata), and marsh elder (Iva frutescens). Unlike its relative, the marsh wren (Cistothorus palustris), the sedge wren avoids cattail (Typha spp.) marshes. Rather, sedge wrens favor marshes containing sedges, grasses, rushes, scattered shrubs, and other emergent vegetation. Sedge wrens typically exhibit low fidelity to breeding sites each year, possibly due to changes in water levels or vegetative structure and composition. -

Species Assessment for Sedge Wren

Species Status Assessment Class: Birds Family: Troglodytidae Scientific Name: Cistothorus platensis Common Name: Sedge wren Species synopsis: Previously known as the short-billed marsh wren, the sedge wren is an inhabitant of wet meadows, hay fields, and marshes. This wren’s use of ephemeral habitats drives its tendency to abandon areas as they become too wet or too dry and move to new areas. Within a season, sedge wrens may raise one brood in May and June and then move to a southern or northeastern part of the range to raise a second brood in July and August. This pattern can make detection and monitoring by traditional methods unreliable. Little is known of the life history or demographics of this species. In the Prairie Pothole region, where sedge wren is most abundant, Breeding Bird Survey data show increasing long-term and short-term trends: 5.6% increase per year from 1966 to 2010 and 1.0% increase per year from 2000 to 2010. Significant declining trends were noted in the Northeast beginning in the 1950s due to destruction of wetlands. In response to this decline, sedge wren is now listed as Endangered in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Vermont. It is listed as Threatened in New York. In New York, where it is at the far eastern edge of its range, sedge wren was historically a sparse nester and it remains so today. Since the mid-1980s, sedge wren occupancy in New York has increased by 26% as documented by the second Breeding Bird Atlas, though McGowan (2008) cautions that this species may have been overlooked during the first Atlas. -

Massachusetts Vulnerability Assessment 2016 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Animal Species Profiles

Massachusetts Vulnerability Assessment 2016 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Animal Species Profiles Prepared by Toni Lyn Morelli and Jennifer R. Smetzer June 2016 1 Preface These species profiles were produced for the 2016 Massachusetts Rapid Assessment Protocol of their Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN). Each profile summarizes what is known about specific SGCN species responses to climate change to date and anticipated under future scenarios and highlights where other factors are expected to exacerbate the effects of climate change. This information was obtained through a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature, primarily using the ISI Web of Knowledge to search for papers on each species related to “climate”, “temperature”, “drought”, “flood”, or “precipitation”. A substantial amount of information was available from the Massachusetts Climate Action Tool, a project produced by Scott Jackson, Michelle Staudinger, Steve DeStefano, Toni Lyn Morelli, and others. In addition, Staudinger et al.'s 2015 Integrating Climate Change into Northeast and Midwest State Wildlife Action Plans was an important resource for these reports, including work by Colton Ellison and Stephen Jane. Funding for these reports was provided by Massachusetts Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Department of Interior Northeast Climate Science Center. 2 Species Profiles AMPHIBIANS ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Blue-spotted -

Marsh Bird Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2010-2015 Marsh Birds Guild American Bittern Botaurus lentiginosus Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps American Coot Fulica americana Purple Gallinule Porphyrula martinica Black Rail Laterallus jamaicensis Sedge Wren Cistothorus platensis Clapper Rail Rallus longirostris Sora Porzana carolina Common Gallinule Gallinula galeata Yellow Rail Coturnicops noveboracensis King Rail Rallus elegans Virginia Rail Rallus limicola Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis Wilson’s Snipe Gallinago delicata NOTE: The Black Rail is described in more detail in a separate species account. The Wilson’s Snipe is also referenced in the Migratory Shorebirds Guild. Contributor (2005): John E. Cely Reviewed and Edited (2012): Craig Watson (USFWS); (2013) Lisa Smith and Christy Hand (SCDNR) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions The members of the Marsh Birds Guild vary widely in appearance and size. The rails and bitterns have long, slender beaks and stilt-like legs for wading while the coot and grebe have shorter legs with webbed feet for paddling. Sizes for the species vary from the large American Bittern at 58 cm (23 in.) to the small Sedge Wren at 11 cm (4.5 in.). The most colorful of the group is the Purple Gallinule. The male has plumage in shades of green, purple, and blue with bright American Bittern photo by BLM yellow feet and long toes (Sauer et al. 2000). The Black Rail is the smallest North American rail measuring 10-15 cm (4 -6 in.) in length and 35 g (1.2 oz.) in weight (Eddleman et al. 1994). Adult rails have strikingly red irises, a dark gray to blackish head, gray neck and breast, rufous nape, and a black and white patterned back. -

Sedge Wren Cistothorus Platensis

Sedge Wren Cistothorus platensis To judge from available reports, the diminu tive Sedge Wren (formerly called the Short billed Marsh Wren) is one of the rarest regu larly breeding species in Vermont. It has been proposed for Threatened Species status in the state. Possible breeders were found by Atlas Project workers at only nine locations, and nesting was confirmed at only two of these. The species' apparent scarcity may re sult from a variety of environmental and be havioral factors. The Sedge Wren is a shy bird with an insectlike song; it nests late in the summer in moist grassy and sedge habi tats that are only nominally interesting to ably arrive and commence actual breeding many birders. Colonies of Sedge Wrens have much later, perhaps as late as July. Males little nest-site tenacity from year to year establish and vigorously defend relatively (Burns I982); areas searched unsuccessfully large all-purpose territories of 0.2 ha (0-4 during one year may have been occupied a), in which they build a series of 7 to I3 in other years when efforts were directed spherical, dummy nests over a period of 2 to elsewhere. 3 months (Burns I982). The female selects a Vermont lies near the northeastern edge nest and lines it with grass, sedge, and fea of the Sedge Wren's breeding range. Al thers over a period of 3 days; the 7-egg clutch though clear-cutting in the I800s created is then initiated and added to daily. A q-day vast expanses of grassland in the state, in incubation period starts before completion tensive pasturing of sheep and other live of the clutch; hatching therefore extends stock at that time probably rendered these over a 2- to 3-day period. -

Sedge Wren Cistothorusplatensis

sedge wren Cistothorus platensis Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The sedge wren is also known as the short-billed Class: Aves marsh wren. This tiny bird is about four to four and Order: Passeriformes one-half inches in length (tail tip to bill tip in preserved specimen). It has a buff-colored area Family: Troglodytidae under the tail. The crown and back feathers are ILLINOIS STATUS streaked. The thin bill is slightly curved downward. This bird tends to hold its tail in an upright position. common, native BEHAVIORS The sedge wren is an uncommon migrant, uncommon summer resident and very rare winter resident in Illinois. It lives in wet grasses, sedge meadows, weedy fields, clover, alfalfa fields and shrub areas. Most spring migrants appear in April and May. Eggs are produced from June through August. The nest is globe-shaped with a side entrance and made of dried or green sedges. The nest is built to incorporate living plants as well as dead plant materials. The male builds several dummy nests in addition to the nest in which the eggs are laid. Four to seven, white eggs are deposited by the female, and she incubates them over the 12- to 14-day incubation period. Usually two broods are raised. Fall migration usually starts in October. The sedge wren winters as far south as northern Mexico. This bird eats insects and spiders. It may sing all day and all night. The song is a chattering “chap chap chap chap chapper-rrr.” © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Nesting Ecology of Sedge Wrens in Hall County, Nebraska Gary R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Bird Review Nebraska Ornithologists' Union 6-1989 Nesting Ecology of Sedge Wrens in Hall County, Nebraska Gary R. Lingle The Platte River Whooping Crane Trust Paul A. Bedell The Platte River Whooping Crane Trust Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebbirdrev Part of the Poultry or Avian Science Commons, and the Zoology Commons Lingle, Gary R. and Bedell, Paul A., "Nesting Ecology of Sedge Wrens in Hall County, Nebraska" (1989). Nebraska Bird Review. 147. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebbirdrev/147 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Ornithologists' Union at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Bird Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Lingle & Bedell, "Nesting Ecology of Sedge Wrens in Hall County, Nebraska," from Nebraska Bird Review (June 1989) 57(2). Copyright 1989, Nebraska Ornithologists' Union. Used by permission. Nebraska Bird Review 47 NESTING ECOLOGY OF SEDGE WRENS IN HALL COUNTY, NEBRASKA The status of the Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis) in Nebraska is not well known. Cink (1973) summarized summer records from 1867 to 1971 and described only a few nest records. One nest discovered on 28 August 1902 at Capitol Beach, Lancaster Co., was assumed empty, apparently because of the late date. Bedell (1987) recorded July and August sightings in southcentral Nebraska and raised the question of whether these birds were migrants or nesting. Sedge Wrens are frequently polygynous (Crawford 1977, Burns 1982) and may exhibit two waves of nesting effort in some areas (Burns 1982). -

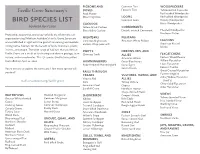

Bird Species List

PIGEONS AND Common Tern WOODPECKERS DOVES Forster’s Tern Yellow-bellied Sapsucker Faville Grove Sanctuary’s Rock Pigeon Red-headed Woodpecker Mourning Dove LOONS Red-bellied Woodpecker BIRD SPECIES LIST Common Loon Downy Woodpecker CUCKOOS Hairy Woodpecker Updated April 2020 Yellow-billed Cuckoo CORMORANTS Black-billed Cuckoo Double-crested Cormorant Pileated Woodpecker Protecting, supporting, and enjoying birds are what make our Northern Flicker organization sing! Madison Audubon’s Faville Grove Sanctuary NIGHTJARS PELICANS American White Pelican FALCONS was established in 1998 with the goal of conserving and reestab- Common Nighthawk Eastern Whip-poor-will American Kestrel lishing native habitats for the benefit of birds, mammals, plants, Merlin insects, and people. The wide range of habitats that you find at SWIFTS HERONS, IBIS, AND Faville Grove are a result of fascinating and diverse geology, burn Chimney Swift ALLIES FLYCATCHERS history, and microclimates. This 171-species bird list was pulled American Bittern Eastern Wood-Pewee from eBird on April 22, 2020. HUMMINGBIRDS Great Blue Heron Willow Flycatcher Ruby-throated Hummingbird Great Egret Least Flycatcher Eastern Phoebe You’re invited to explore the sanctuary. How many species will Green Heron Great Crested Flycatcher you find? RAILS THROUGH CRANES VULTURES, HAWKS, AND Eastern Kingbird Alder/Willow Flycatcher Virginia Rail ALLIES (Traill’s) madisonaudubon.org/faville-grove Sora Turkey Vulture Olive-sided Flycatcher American Coot Osprey Alder Flycatcher Sandhill Crane Northern -

Sedge Wren (Cistothorus Platensis) Brian Johnson

Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis) Brian Johnson Iron Co., MI 6/18/2005 © Elizabeth Rogers (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) Diminutive in stature and seemingly loathe to and South Dakota across Minnesota and Wisconsin to Lake Michigan (Sauer et al. 2008). fly, and then doing so in a laborious and fluttering fashion, the sprightly Sedge Wren is a Distribution rather secretive bird that generally keeps As shown by both Michigan atlases, Sedge frustratingly out of view in lush vegetation. Wrens range widely across both peninsulas, However, the species boasts a belligerent and though much of the NLP is relatively sparsely energetic demeanor typical to other wrens, and populated. Only two counties lacked records it is very aggressive towards conspecifics and during MBBA II (six during MBBA I). The other grassland birds. Males sometimes eastern SLP and large areas of the UP were simultaneously mate with two females poorly represented during MBBA I, but the (Crawford 1977, Burns 1982), and both sexes species was distributed much more evenly destroy the eggs of other Sedge Wrens and other during MBBA II. On a local level, populations species breeding nearby (Picman and Picman demonstrate high motility and low site fidelity. 1980). Although males usually sing from low, semi-concealed perches, they do so persistently, As its name reflects, the species is highly not only continuing later in the day than several dependent on dense mats of tall, usually course- other species, but their harsh, staccato rattle is bladed grasses and sedges. Moist or frequently uttered during all hours of the night ephemerally wet situations are another key (and sometimes in a vigorous banter with their requirement, and Sedge Wrens typically avoid neighbors).