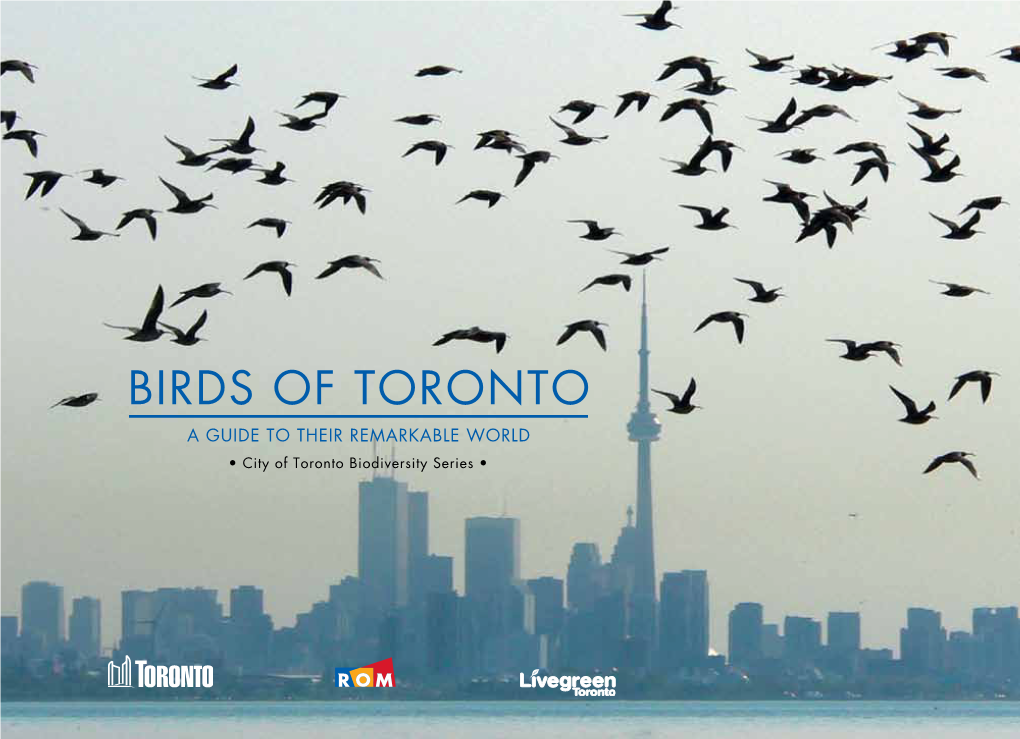

Birds of Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predation by Gray Catbird on Brown Thrasher Eggs

March 2004 Notes 101 PREDATION BY GRAY CATBIRD ON BROWN THRASHER EGGS JAMES W. RIVERS* AND BRETT K. SANDERCOCK Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (JWR) Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506 (BKS) Present address of JWR: Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106 *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT The gray catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) has been documented visiting and breaking the eggs of arti®cial nests, but the implications of such observations are unclear because there is little cost in depredating an undefended nest. During the summer of 2001 at Konza Prairie Bio- logical Station, Kansas, we videotaped a gray catbird that broke and consumed at least 1 egg in a brown thrasher (Toxostoma rufum) nest. Our observation was consistent with egg predation because the catbird consumed the contents of the damaged egg after breaking it. The large difference in body mass suggests that a catbird (37 g) destroying eggs in a thrasher (69 g) nest might risk injury if caught in the act of predation and might explain why egg predation by catbirds has been poorly documented. Our observation indicated that the catbird should be considered as an egg predator of natural nests and that single-egg predation of songbird nests should not be attributed to egg removal by female brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater) without additional evidence. RESUMEN El paÂjaro gato gris (Dumetella carolinensis) ha sido documentado visitando y rompien- do los huevos de nidos arti®ciales, pero las implicaciones de dichas observaciones no son claras porque hay poco costo por depredar un nido sin defensa. -

The Mark of the Japanese Murrelet (Synthliboramphus Wumizusume): a Study of Song and Stewardship in Japan’S Inland Sea

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2019 The aM rk of the Japanese Murrelet (Synthliboramphus wumizusume): A study of song and stewardship in Japan’s Inland Sea Charlotte Hyde The Mark of the Japanese Murrelet (Synthliboramphus wumizusume): A study of song and stewardship in Japan’s Inland Sea Charlotte Hyde In partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts Degree in Environmental Analysis, 2018-2019 academic year, Pomona College, Claremont, California Readers: Nina Karnovsky Wallace Meyer Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nina Karnovsky for introducing me to her work in Kaminoseki and for allowing me to join this incredible project, thereby linking me to a community of activists and scientists around the world. I am also so appreciative for her role as my mentor throughout my years as an undergraduate and for helping me develop my skills and confidence as a scholar and ecologist. Thank you also to my reader Wallace Meyer for his feedback on my writing and structure. I am so thankful for the assistance of Char Miller, who has worked tirelessly to give valuable advice and support to all seniors in the Environmental Analysis Department throughout their thesis journeys. Thank you to Marc Los Huertos for his assistance with R and data analysis, without which I would be hopelessly lost. I want to thank my peers in the Biology and Environmental Analysis departments for commiserating with me during stressful moments and for providing a laugh, hug, or shoulder to cry on, depending on the occasion. Thank you so much to my parents, who have supported me unconditionally throughout my turbulent journey into adulthood and who have never doubted my worth as a person or my abilities as a student. -

Rare Birds of California Now Available! Price $54.00 for WFO Members, $59.99 for Nonmembers

Volume 40, Number 3, 2009 The 33rd Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2007 Records Daniel S. Singer and Scott B. Terrill .........................158 Distribution, Abundance, and Survival of Nesting American Dippers Near Juneau, Alaska Mary F. Willson, Grey W. Pendleton, and Katherine M. Hocker ........................................................191 Changes in the Winter Distribution of the Rough-legged Hawk in North America Edward R. Pandolfino and Kimberly Suedkamp Wells .....................................................210 Nesting Success of California Least Terns at the Guerrero Negro Saltworks, Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2005 Antonio Gutiérrez-Aguilar, Roberto Carmona, and Andrea Cuellar ..................................... 225 NOTES Sandwich Terns on Isla Rasa, Gulf of California, Mexico Enriqueta Velarde and Marisol Tordesillas ...............................230 Curve-billed Thrasher Reproductive Success after a Wet Winter in the Sonoran Desert of Arizona Carroll D. Littlefield ............234 First North American Records of the Rufous-tailed Robin (Luscinia sibilans) Lucas H. DeCicco, Steven C. Heinl, and David W. Sonneborn ........................................................237 Book Reviews Rich Hoyer and Alan Contreras ...........................242 Featured Photo: Juvenal Plumage of the Aztec Thrush Kurt A. Radamaker .................................................................247 Front cover photo by © Bob Lewis of Berkeley, California: Dusky Warbler (Phylloscopus fuscatus), Richmond, Contra Costa County, California, 9 October 2008, discovered by Emilie Strauss. Known in North America including Alaska from over 30 records, the Dusky is the Old World Warbler most frequent in western North America south of Alaska, with 13 records from California and 2 from Baja California. Back cover “Featured Photos” by © Kurt A. Radamaker of Fountain Hills, Arizona: Aztec Thrush (Ridgwayia pinicola), re- cently fledged juvenile, Mesa del Campanero, about 20 km west of Yecora, Sonora, Mexico, 1 September 2007. -

Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative

2021 GRANT SLATE Atlantic Flyway Shorebird Initiative NFWF CONTACTS Bridget Collins Senior Manager, Private Lands and Bird Conservation, [email protected] 202-297-6759 Scott Hall Senior Scientist, Bird Conservation [email protected] 202-595-2422 PARTNERS Red knots ABOUT NFWF Chartered by Congress in 1984, OVERVIEW the National Fish and Wildlife The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), the US Fish and Wildlife Service and Foundation (NFWF) protects and Southern Company announce a fourth year of funding for the Atlantic Flyway Shorebird restores the nation’s fish, wildlife, program. Six new or continuing shorebird conservation grants totaling nearly $625,000 plants and habitats. Working with were awarded. These six awards generated $656,665 in match from grantees, for a total federal, corporate and individual conservation impact of $1.28 million. Overall, this slate of projects will improve habitat partners, NFWF has funded more management on more than 50,000 acres, conduct outreach to more than 100,000 people, than 5,000 organizations and and will complete a groundbreaking, science-based toolkit to help managers successfully generated a total conservation reduce human disturbance of shorebirds year-round. impact of $6.1 billion. The Atlantic Flyway Shorebirds program aims to increase populations for three focal Learn more at www.nfwf.org species by improving habitat functionality and condition at critical sites, supporting the species’ full annual lifecycles. The Atlantic Flyway Shorebird business plan outlines NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS strategies to address key stressors for the American oystercatcher, red knot and whimbrel. 1133 15th Street, NW Suite 1000 approaches to address habitat loss, predation, and human disturbance. -

Coyote Reservoir & Harvey Bear..…

Coyote Reservoir & Harvey Bear..…. February 24, south Santa Clara County Quick Overview – Watching the weather reports we all saw the storm coming, but a group of adventurous souls arrived with all their rain gear and ready to go regardless of the elements, and what a day we had! Once east of Gilroy and traveling through the country roads we realized that soaking wet birds create unique ID challenges. With characteristic feathers in disarray and the wet plumages now appearing much darker we had to leave some questionable birds off our list. We had wanted to walk some of the trails that make up the new Harvey Bear Ranch Park, but the rain had us doing most of our birding from the cars which was easy along Coyote Reservoir Road as it parallels the lake. It also makes it easy when no one else is in the park. We could stop anywhere we wanted and we were not in anyone’s way – a birder’s dream come true! Watching Violet Green Swallows by the hundreds reminded us all that spring is near. And at one stop we got four woodpecker species. Ending our day watching Bald Eagles grasp fish at the surface of the water was worth our getting all wet! And I’ll not soon forget our close encounter with the dam’s Rufous Crowned Sparrow. Since we started our day at the south entrance of the park we ended Rufous Crowned Sparrow our day at the north entrance. It was here we listened to above and hard working Western Meadowlarks and watched a Say’s Phoebe. -

Red Rock Lakes Total Species: National Wildlife Refuge for Birds Seen Not on This List Please Contact the Refuge with Species, Location, Time, and Date

Observer: Address: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Weather: Date: Time: Red Rock Lakes Total Species: National Wildlife Refuge For birds seen not on this list please contact the refuge with species, location, time, and date. Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Birding Guide 27650B South Valley Road Lima, MT 59739 Red Rock Lakes National [email protected] email Wildlife Refuge and the http://www.fws.gov/redrocks/ 406-276-3536 Centennial Valley, Montana 406-276-3538 fax For Hearing impaired TTY/Voice: 711 State transfer relay service (TRS) U.S Fish & Wildlife Service http://www.fws.gov/ For Refuge Information 1-800-344-WILD(9453) July 2013 The following birds have been observed in the Centennial Valley and are Red Rock Lakes considered rare or accidental. These birds are either observed very infre- quently in highly restrictive habitat types or are out of their normal range. National Wildlife Refuge Artic Loon Black-bellied Plover Winter Wren Clark’s Grebe Snowy Plover Northern Mockingbird Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge is located in the scenic and iso- lated Centennial Valley of southwestern Montana, approximately 40 miles Great Egret Red-necked Phalarope Red-eyed Vireo west of Yellowstone National Park. The refuge has a vast array of habitat, Mute Swan American Woodcock Yellow-breasted Chat ranging from high elevation wetland and prairie at 6,600 feet, to the harsh alpine habitat of the Centennial Mountains at 9,400 feet above sea level. It Black Swan Pectoral Sandpiper Common Grackle is this diverse, marsh-prairie-sagebrush-montane environment that gives Ross’ Goose Dunlin Northern Oriole Red Rock Lakes its unique character. -

Factors Affecting Feeding and Brooding of Brown Thrasher Nestlings.-The Nest- Ling Period Is a Particularly Stressful Time in the Lives of Birds

GENERAL NOTES 297 wind. An adult California Gull (Larus c&ornicus) was flying east 5 m above the water, 50 m from the shore, close to 150 Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) that were foraging low over the water. One swallow, heading west, passed 1 m below the gull, which dropped suddenly and caught the swallow with its bill, glided for a few meters and settled on the water. The gull proceeded to manipulate the swallow in its bill for 30 set before swallowing the still moving bird head first. The gull sat on the water for 20 min, then continued its flight to the east. Most reports of adult birds being taken by gulls have occurred while the prey were on land or water, e.g., Manx Shearwater (Puffi nus &&us) and Common Puffins (Fratercula arctica) in nesting colonies as they go to and from their burrows (Harris 1965), sick or injured birds up to the size of geese (Witherby 1948), Rock Doves (Columba &via) (Jyrkkanen 1975) and Eurasian Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) (Drost 1958) at grain piles and ground-dwelling birds which associate with gulls (e.g., Witherby 1948). Gull predation of adult birds on water is much rarer but does occur (Hafft, Condor 73:253, 1971). Attacks and capture of avian prey on the wing has rarely been reported and generally occurs over sea on migration (Drost 1958). Bannerman (1962) reports Herring Gulls (L. argentatus) capturing and eating Redwings (Turdus musicus) and Eurasian Blackbirds (2.’ merula) as they migrate over water by knocking the weary birds into the water. -

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Ancient Murrelet Synthliboramphus Antiquus

Major: Ancient Murrelet Synthliboramphus antiquus colony attendance at Langara 233 ANCIENT MURRELET SYNTHLIBORAMPHUS ANTIQUUS COLONY ATTENDANCE AT LANGARA ISLAND ASSESSED USING OBSERVER COUNTS AND RADAR IN RELATION TO TIME AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS HEATHER L. MAJOR1,2 1Centre for Wildlife Ecology, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, 8888 University Drive, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada 2Current address: Department of Biological Sciences, University of New Brunswick, P.O. Box 5050, Saint John, NB E2L 4L5, Canada ([email protected]) Received 10 June 2016, accepted 26 July 2016 SUMMARY MAJOR, H.L. 2016. Ancient Murrelet Synthliboramphus antiquus colony attendance at Langara Island assessed using observer counts and radar in relation to time and environmental conditions. Marine Ornithology 44: 233–240. The decision to attend a colony on any given day or night is arguably the result of a trade-off between survival and reproductive success. It is often difficult to study this trade-off, as monitoring patterns of colony attendance for nocturnal burrow-nesting seabirds is challenging. Here, I 1) examined the effectiveness of monitoring Ancient Murrelet colony arrivals using marine radar, and 2) evaluated differences in colony attendance behavior in relation to time, light, and weather. I found a strong correlation between the number of Ancient Murrelets counted by observers in the colony and the number of radar targets counted, with estimated radar target counts being ~95 times higher than observer counts. My hypothesis that patterns of colony attendance are related to environmental conditions (i.e. light and weather) and that this relationship changes with time after sunset was supported. -

1 Sexual Selection in the American Goldfinch

Sexual Selection in the American Goldfinch (Spinus tristis): Context-Dependent Variation in Female Preference Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Donella S. Bolen, M.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee: Ian M. Hamilton, Advisor J. Andrew Roberts, Advisor Jacqueline Augustine 1 Copyrighted by Donella S. Bolen 2019 2 Abstract Females can vary in their mate choice decisions and this variability can play a key role in evolution by sexual selection. Variability in female preferences can affect the intensity and direction of selection on male sexual traits, as well as explain variation in male reproductive success. I looked at how consistency of female preference can vary for a male sexual trait, song length, and then examined context-dependent situations that may contribute to variation in female preferences. In Chapter 2, I assessed repeatability – a measure of among-individual variation – in preference for male song length in female American goldfinches (Spinus tristis). I found no repeatability in preference for song length but did find an overall preference for shorter songs. I suggest that context, including the social environment, may be important in altering the expression of female preferences. In Chapter 3, I assessed how the choices of other females influence female preference. Mate choice copying, in which female preference for a male increases if he has been observed with other females, has been observed in several non-monogamous birds. However, it is unclear whether mate choice copying occurs in socially monogamous species where there are direct benefits from choosing an unmated male. -

Owls-Of-Nh.Pdf

Lucky owlers may spot the stunning great gray owl – but only in rare years when prey is sparse in its Arctic habitat. ©ALAN BRIERE PHOTO 4 January/February 2009 • WILDLIFE JOURNAL OWLSof NEW HAMPSHIRE Remarkable birds of prey take shelter in our winter woods wls hold a special place in human culture and folklore. The bright yellow and black eyes surrounded by an orange facial disc Oimage of the wise old owl pervades our literature and conjures and a white throat patch. up childhood memories of bedtime stories. Perhaps it’s their circular Like most owls, great horned owls are not big on building their faces and big eyes that promote those anthropomorphic analogies, own nests. They usually claim an old stick nest of another species or maybe it is owls’ generally nocturnal habits that give them an air – perhaps one originally built by a crow, raven or red-tailed hawk. In of mystery and fascination. New Hampshire, great horned owls favor nest- New Hampshire’s woods and swamps are ing in great blue heron nests in beaver-swamp home to several species of owls. Four owl spe- BY IAIN MACLEOD rookeries. Many times, while checking rooker- cies regularly nest here: great horned, barred, ies in early spring, I’ll see the telltale feather Eastern screech and Northern saw-whet. One other species, the tufts sticking up over the edge of a nest right in the middle of all long-eared owl, nests sporadically in the northern part of the state. the herons. Later in the spring, I’ll return and see a big fluffy owlet None of these species is rare enough to be listed in the N.H. -

Barred Owl (Strix Varia)

Wild Things in Your Woodlands Barred Owl (Strix varia) The barred owl is a large bird, up to 20 inches long, with a wingspan of 44 inches. It is gray-brown in color, with whitish streaks on the back and head, brown horizontal bars on its white chest, and vertical bars on its belly. This owl has a round face without ear tufts, and a whitish facial disk with dark concentric rings around brown eyes. Males and females look similar, but females can weigh about one third more than males. “Who cooks for you, who cooks for you all?” This is the familiar call of the barred owl defending its territory or attracting a mate. If you live in or near a heavily wooded area with mature forest, particularly if there is also a stream or other body of water nearby, this sound is probably familiar. Barred owls are the most vocal of our owls, and most often are heard calling early at night and at dawn. They call year-round, but courtship activities begin in February and breeding takes place primarily in March and April. Nesting in cavities or abandoned hawk, squirrel, or crow nests, the female sits on a nest of 1-5 eggs for 28 to 33 days. During this time, the male brings food to her. Once the eggs have hatched, both parents care for the fledglings for at least 4 months. Barred owls mate for life, reuse their nest site for many years, and maintain territories from 200 – 400 acres in size. Barred owls are strongly territorial and remain in their territories for most, if not all, of the year.