The Helminths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Literature Survey of Common Parasitic Zoonoses Encountered at Post-Mortem Examination in Slaughter Stocks in Tanzania: Economic and Public Health Implications

Volume 1- Issue 5 : 2017 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000419 Erick VG Komba. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Research Article Open Access A Literature Survey of Common Parasitic Zoonoses Encountered at Post-Mortem Examination in Slaughter Stocks in Tanzania: Economic and Public Health Implications Erick VG Komba* Department of Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, Sokoine University of Agriculture, Tanzania Received: September 21, 2017; Published: October 06, 2017 *Corresponding author: Erick VG Komba, Senior lecturer, Department of Veterinary Medicine and Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Sokoine University of Agriculture, P.O. Box 3021, Morogoro, Tanzania Abstract Zoonoses caused by parasites constitute a large group of infectious diseases with varying host ranges and patterns of transmission. Their public health impact of such zoonoses warrants appropriate surveillance to obtain enough information that will provide inputs in the design anddistribution, implementation prevalence of control and transmission strategies. Apatterns need therefore are affected arises by to the regularly influence re-evaluate of both human the current and environmental status of zoonotic factors. diseases, The economic particularly and in view of new data available as a result of surveillance activities and the application of new technologies. Consequently this paper summarizes available information in Tanzania on parasitic zoonoses encountered in slaughter stocks during post-mortem examination at slaughter facilities. The occurrence, in slaughter stocks, of fasciola spp, Echinococcus granulosus (hydatid) cysts, Taenia saginata Cysts, Taenia solium Cysts and ascaris spp. have been reported by various researchers. Information on these parasitic diseases is presented in this paper as they are the most important ones encountered in slaughter stocks in the country. -

Hymenolepis Nana) in the Southern United States.1

HUMAN INFESTATION WITH THE DWARF TAPEWORM (HYMENOLEPIS NANA) IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES.1 BY Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/23/1/25/182937 by guest on 27 September 2021 G. F. OTTO. (Received for publication September 6, 1935.) Human infestation with the dwarf tapeworm has been reported from a wide variety of places in the United States but most of the evidence suggests that it is largely restricted to the southern part of the country. Even in the southern United States the incidence is low according to most of the data. Of the older surveys Greil (1915) re- ports 6 per cent dwarf tapeworm in 665 children examined in Alabama. The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hook- worm Disease Reports for 1914 and 1915 record from 0 to 2.5 per cent dwarf tapeworm in eleven southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Geor- gia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, Ten- nessee, Texas, and Virginia) with an average of 1.8 per cent in the 141,247 persons examined. Wood (1912) tabulated the results of 62,786 routine fecal examinations made in the state laboratories of eight southern states (Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missis- sippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) and found an average of less than 1 per cent infection with this worm. Of the more recent reports on the frequency of the dwarf tapeworm in the general population, three are based on extensive surveys. Spindler (1929) records that 3.6 per cent of the 2,152 persons of all ages examined in southwest Virginia were positive; Keller, Leathers, and Bishop (1932) report 3.5, 2.9, and 1.5 per cent in eastern, central and western Tennessee; and Keller and Leathers (1934) report 0.4 per cent in Mississippi. -

Gastrointestinal Helminthic Parasites of Habituated Wild Chimpanzees

Aus dem Institut für Parasitologie und Tropenveterinärmedizin des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Gastrointestinal helminthic parasites of habituated wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in the Taï NP, Côte d’Ivoire − including characterization of cultured helminth developmental stages using genetic markers Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Veterinärmedizin an der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Sonja Metzger Tierärztin aus München Berlin 2014 Journal-Nr.: 3727 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung des Fachbereichs Veterinärmedizin der Freien Universität Berlin Dekan: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jürgen Zentek Erster Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Georg von Samson-Himmelstjerna Zweiter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer Dritter Gutachter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Achim Gruber Deskriptoren (nach CAB-Thesaurus): chimpanzees, helminths, host parasite relationships, fecal examination, characterization, developmental stages, ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial DNA Tag der Promotion: 10.06.2015 Contents I INTRODUCTION ---------------------------------------------------- 1- 4 I.1 Background 1- 3 I.2 Study objectives 4 II LITERATURE OVERVIEW --------------------------------------- 5- 37 II.1 Taï National Park 5- 7 II.1.1 Location and climate 5- 6 II.1.2 Vegetation and fauna 6 II.1.3 Human pressure and impact on the park 7 II.2 Chimpanzees 7- 12 II.2.1 Status 7 II.2.2 Group sizes and composition 7- 9 II.2.3 Territories and ranging behavior 9 II.2.4 Diet and hunting behavior 9- 10 II.2.5 Contact with humans 10 II.2.6 -

Fishery Bulletin/U S Dept of Commerce National Oceanic

Abstract.-Seventeen species of parasites representing the Cestoda, Parasite Fauna of Three Species Nematoda, Acanthocephala, and Crus tacea are reported from three spe of Antarctic Whales with cies of Antarctic whales. Thirty-five sei whales Balaenoptera borealis, Reference to Their Use 106 minke whales B. acutorostrata, and 35 sperm whales Pkyseter cato as Potentia' Stock Indicators don were examined from latitudes 30° to 64°S, and between longitudes 106°E to 108°W, during the months Murray D. Dailey ofNovember to March 1976-77. Col Ocean Studies Institute. California State University lection localities and regional hel Long Beach, California 90840 minth fauna diversity are plotted on distribution maps. Antarctic host-parasite records from Wolfgang K. Vogelbein B. borealis, B. acutorostrata, and P. Virginia Institute of Marine Science catodon are updated and tabulated Gloucester Point. Virginia 23062 by commercial whaling sectors. The use of acanthocephalan para sites of the genus Corynosoma as potential Antarctic sperm whale stock indicators is discussed. The great whales of the southern hemi easiest to find (Gaskin 1976). A direct sphere migrate annually between result of this has been the successive temperate breeding and Antarctic overexploitation of several major feeding grounds. However, results of whale species. To manage Antarctic Antarctic whale tagging programs whaling more effectively, identifica (Brown 1971, 1974, 1978; Ivashin tion and determination of whale 1988) indicate that on the feeding stocks is of high priority (Schevill grounds circumpolar movement by 1971, International Whaling Com sperm and baleen whales is minimal. mission 1990). These whales apparently do not com The Antarctic whaling grounds prise homogeneous populations were partitioned by the International whose members mix freely through Whaling Commission into commer out the entire Antarctic. -

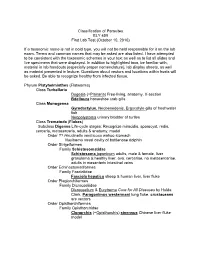

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010)

Classification of Parasites BLY 459 First Lab Test (October 10, 2010) If a taxonomic name is not in bold type, you will not be held responsible for it on the lab exam. Terms and common names that may be asked are also listed. I have attempted to be consistent with the taxonomic schemes in your text as well as to list all slides and live specimens that were displayed. In addition to highlighted taxa, be familiar with, material in lab handouts (especially proper nomenclature), lab display sheets, as well as material presented in lecture. Questions about vectors and locations within hosts will be asked. Be able to recognize healthy from infected tissue. Phylum Platyhelminthes (Flatworms) Class Turbellaria Dugesia (=Planaria ) Free-living, anatomy, X-section Bdelloura horseshoe crab gills Class Monogenea Gyrodactylus , Neobenedenis, Ergocotyle gills of freshwater fish Neopolystoma urinary bladder of turtles Class Trematoda ( Flukes ) Subclass Digenea Life-cycle stages: Recognize miracidia, sporocyst, redia, cercaria , metacercaria, adults & anatomy, model Order ?? Hirudinella ventricosa wahoo stomach Nasitrema nasal cavity of bottlenose dolphin Order Strigeiformes Family Schistosomatidae Schistosoma japonicum adults, male & female, liver granuloma & healthy liver, ova, cercariae, no metacercariae, adults in mesenteric intestinal veins Order Echinostomatiformes Family Fasciolidae Fasciola hepatica sheep & human liver, liver fluke Order Plagiorchiformes Family Dicrocoeliidae Dicrocoelium & Eurytrema Cure for All Diseases by Hulda Clark, Paragonimus -

Arthropods of Medical Importance in Ohio

ARTHROPODS OF MEDICAL IMPORTANCE IN OHIO CHARLES O. MASTERS Sanitarian, Licking and Knox Counties, Ohio It is rather difficult to state with authority that arthropods, which make up about 86 percent of the world's animal species, are not of medical importance in the state of Ohio. Public health workers know only too well that man is suscep- tible to many diseases, and when the causative organisms are present in an area inhabited by host animals and vectors as well as by man, troubles very often result. This was demonstrated very nicely in Aurora, Ohio, in 1934 when the causative organism of malaria was brought into that region. The other three necessary factors were already there (Hoyt and Worden, 1935). When one considers that many centers of infection of some of the world's most serious human illnesses are now only hours away by plane, he can't help but wonder what the situation is in Ohio, relative to these other necessary factors. The opening of northern Ohio ports to foreign shipping also suggests the possibility of the introduction of unusual organisms. This is an approach to that particular aspect. The phylum Arthropoda is divided into five classes of animals: Insecta, Crustacea, Chilopoda (centipedes), Diplopoda (millipedes), and Arachnida (spiders, scorpions, mites, and ticks). Representatives of these various groups which are found in Ohio and which might have some medical significance will be discussed. There are nine species of mosquitoes breeding in the state of Ohio which are of medical interest. These are as follows: Anopheles quadrimaculatus, the vector of malaria in eastern United States, is not only common in weedy Ohio ponds but seems to be increasing in number. -

Fleas and Flea-Borne Diseases

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 14 (2010) e667–e676 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Review Fleas and flea-borne diseases Idir Bitam a, Katharina Dittmar b, Philippe Parola a, Michael F. Whiting c, Didier Raoult a,* a Unite´ de Recherche en Maladies Infectieuses Tropicales Emergentes, CNRS-IRD UMR 6236, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Universite´ de la Me´diterrane´e, 27 Bd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille Cedex 5, France b Department of Biological Sciences, SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA c Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Article history: Flea-borne infections are emerging or re-emerging throughout the world, and their incidence is on the Received 3 February 2009 rise. Furthermore, their distribution and that of their vectors is shifting and expanding. This publication Received in revised form 2 June 2009 reviews general flea biology and the distribution of the flea-borne diseases of public health importance Accepted 4 November 2009 throughout the world, their principal flea vectors, and the extent of their public health burden. Such an Corresponding Editor: William Cameron, overall review is necessary to understand the importance of this group of infections and the resources Ottawa, Canada that must be allocated to their control by public health authorities to ensure their timely diagnosis and treatment. Keywords: ß 2010 International Society for Infectious Diseases. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Flea Siphonaptera Plague Yersinia pestis Rickettsia Bartonella Introduction to 16 families and 238 genera have been described, but only a minority is synanthropic, that is they live in close association with The past decades have seen a dramatic change in the geographic humans (Table 1).4,5 and host ranges of many vector-borne pathogens, and their diseases. -

Coinfection of Schistosoma (Trematoda) with Bacteria, Protozoa and Helminths

CHAPTER 1 Coinfection of Schistosoma (Trematoda) with Bacteria, Protozoa and Helminths ,† ‡ Amy Abruzzi* and Bernard Fried Contents 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Coinfection of Species of Schistosoma and Plasmodium 4 1.2.1. Animal studies 21 1.2.2. Human studies 23 1.3. Coinfection of Schistosoma Species with Protozoans other than in the Genus Plasmodium 24 1.3.1. Leishmania 32 1.3.2. Toxoplasma 32 1.3.3. Entamoeba 34 1.3.4. Trypanosoma 35 1.4. Coinfection of Schistosoma Species with Salmonella 36 1.4.1. Animal studies 36 1.4.2. Human studies 42 1.5. Coinfection of Schistosoma Species with Bacteria other than Salmonella 43 1.5.1. Mycobacterium 43 1.5.2. Helicobacter pylori 49 1.5.3. Staphylococcus aureus 50 1.6. Coinfection of Schistosoma and Fasciola Species 50 1.6.1. Animal studies 57 1.6.2. Human studies 58 * Skillman Library, Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, USA { Epidemiology, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ), Piscataway, New Jersey, USA { Department of Biology, Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, USA Advances in Parasitology, Volume 77 # 2011 Elsevier Ltd. ISSN 0065-308X, DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-391429-3.00005-8 All rights reserved. 1 2 Amy Abruzzi and Bernard Fried 1.7. Coinfection of Schistosoma Species and Helminths other than the Genus Fasciola 59 1.7.1. Echinostoma 59 1.7.2. Hookworm 70 1.7.3. Trichuris 70 1.7.4. Ascaris 71 1.7.5. Strongyloides and Trichostrongyloides 72 1.7.6. Filarids 73 1.8. Concluding Remarks 74 References 75 Abstract This review examines coinfection of selected species of Schisto- soma with bacteria, protozoa and helminths and focuses on the effects of the coinfection on the hosts. -

Possible Influence of the ENSO Phenomenon on the Pathoecology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 2010 Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations Bernardo Arriaza Universidad de Tarapacá, [email protected] Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Adauto Araujo Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública-Fiocruz, [email protected] Nancy C. Orellana Convenio de Desempeño Vivien G. Standen Universidad de Tarapacá, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard Arriaza, Bernardo; Reinhard, Karl; Araujo, Adauto; Orellana, Nancy C.; and Standen, Vivien G., "Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations" (2010). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 10. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 66 Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 105(1): 66-72, February 2010 Possible influence of the ENSO phenomenon on the pathoecology of diphyllobothriasis and anisakiasis in ancient Chinchorro populations Bernardo T Arriaza1/+, Karl J Reinhard2, Adauto -

Clinical Cysticercosis: Diagnosis and Treatment 11 2

WHO/FAO/OIE Guidelines for the surveillance, prevention and control of taeniosis/cysticercosis Editor: K.D. Murrell Associate Editors: P. Dorny A. Flisser S. Geerts N.C. Kyvsgaard D.P. McManus T.E. Nash Z.S. Pawlowski • Etiology • Taeniosis in humans • Cysticercosis in animals and humans • Biology and systematics • Epidemiology and geographical distribution • Diagnosis and treatment in humans • Detection in cattle and swine • Surveillance • Prevention • Control • Methods All OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health) publications are protected by international copyright law. Extracts may be copied, reproduced, translated, adapted or published in journals, documents, books, electronic media and any other medium destined for the public, for information, educational or commercial purposes, provided prior written permission has been granted by the OIE. The designations and denominations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the OIE concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The views expressed in signed articles are solely the responsibility of the authors. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by the OIE in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. –––––––––– The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the World Health Organization or the World Organisation for Animal Health concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records

125 Helminth Parasites (Trematoda, Cestoda, Nematoda, Acanthocephala) of Herpetofauna from Southeastern Oklahoma: New Host and Geographic Records Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 Charles R. Bursey Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University-Shenango, Sharon, PA 16146 Matthew B. Connior Life Sciences, Northwest Arkansas Community College, Bentonville, AR 72712 Abstract: Between May 2013 and September 2015, two amphibian and eight reptilian species/ subspecies were collected from Atoka (n = 1) and McCurtain (n = 31) counties, Oklahoma, and examined for helminth parasites. Twelve helminths, including a monogenean, six digeneans, a cestode, three nematodes and two acanthocephalans was found to be infecting these hosts. We document nine new host and three new distributional records for these helminths. Although we provide new records, additional surveys are needed for some of the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles of the state, particularly those in the western and panhandle regions who remain to be examined for helminths. ©2015 Oklahoma Academy of Science Introduction Methods In the last two decades, several papers from Between May 2013 and September 2015, our laboratories have appeared in the literature 11 Sequoyah slimy salamander (Plethodon that has helped increase our knowledge of sequoyah), nine Blanchard’s cricket frog the helminth parasites of Oklahoma’s diverse (Acris blanchardii), two eastern cooter herpetofauna (McAllister and Bursey 2004, (Pseudemys concinna concinna), two common 2007, 2012; McAllister et al. 1995, 2002, snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina), two 2005, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014a, b, c; Bonett Mississippi mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum et al. 2011). However, there still remains a hippocrepis), two western cottonmouth lack of information on helminths of some of (Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma), one the 257 species of amphibians and reptiles southern black racer (Coluber constrictor of the state (Sievert and Sievert 2011). -

Identity of Diphyllobothrium Spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People Along the Pacific Coast of South America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 4-2010 Identity of Diphyllobothrium spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People along the Pacific Coast of South America Robert L. Rausch University of Washington, [email protected] Ann M. Adams United States Food and Drug Administration Leo Margolis Fisheries Research Board of Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Rausch, Robert L.; Adams, Ann M.; and Margolis, Leo, "Identity of Diphyllobothrium spp. (Cestoda: Diphyllobothriidae) from Sea Lions and People along the Pacific Coast of South America" (2010). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 498. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/498 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. J. Parasitol., 96(2), 2010, pp. 359–365 F American Society of Parasitologists 2010 IDENTITY OF DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM SPP. (CESTODA: DIPHYLLOBOTHRIIDAE) FROM SEA LIONS AND PEOPLE ALONG THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AMERICA Robert L. Rausch, Ann M. Adams*, and Leo MargolisÀ Department of Comparative Medicine and Department of Pathobiology, Box 357190, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-7190. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Host specificity evidently is not expressed by various species of Diphyllobothrium that occur typically in marine mammals, and people become infected occasionally when dietary customs favor ingestion of plerocercoids.