Uhm Phd 9416058 R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND Lagos Cable Car Project USD 20 Million

CLEAN TECHNOLOGY FUND Lagos Cable Car Project USD 20 million March 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 6 3. CTF INVESTMENT CRITERIA 11 4. MONITORING & EVALUATION 13 5. CONCLUSIONS 13 ANNEX I: CTF INVESTMENT CRITERIA CALCULATIONS 14 ANNEX II: RISKS AND MITIGANTS 15 ANNEX III: PROJECT AREA 17 2 Cover Page for CTF Project/Program Approval Request Dedicated Private Sector Programs (DPSP-III) 2. CIF Project 1. Country/Region Nigeria [CIF AU will ID# assign ID] Public 3. Public or Private Private X 4. Project/Program Title Lagos Cable Car Project 5. Is this a private sector program Yes composed of sub-projects? No X 6. Financial Products, Terms and Amounts USD EUR Financial Product (million) (million) Grant 0.00 Fee on grant 0.00 MPIS (for private sector only) 0.00 Public sector loan Harder terms 0.00 Softer terms 0.00 Senior loan 20.00 Senior loans in local currency hedged 0.00 Subordinated debt / mezzanine instruments with income 0.00 Secondparticipation loss guarantees 0.00 Equity 0.00 Subordinated debt/mezzanine instruments with convertible 0.00 Convertiblefeatures grants and contingent recovery grants 0.00 Contingent recovery loans 0.00 First loss guarantees 0.00 Other (please specify) 0.00 Total 7. Implementing MDB(s) AfDB 8. National Implementing Agency NA 9. MDB Focal Point Leandro Azevedo ([email protected]) 10. Brief Description of Project/Program (including objectives and expected outcomes)[c] The project entails the development, construction and operation of the first phase/green line of the Lagos Cable Car Transit (LCCT) project, an aerial cable car public transport system that comprises 4 stations and spans 4.67 km connecting Lagos island to Victoria island. -

OYEWO, ISHOLA SAHEED Address: 33A, Beecroft Street, Lagos Island, Lagos

OYEWO, ISHOLA SAHEED Address: 33a, Beecroft Street, Lagos Island, Lagos. E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 07033904681, 08054522184 OBJECTIVE To work in an organization with or without supervision in order to contribute my quota to the overall achievement of organizational goal while also adding value to myself PERSONAL ATTRIBUTES Self-motivated and result oriented Excellent communication and good interpersonal skill A dedicated team player, flexible, adaptable and able to face new challenge with enthusiasm. Ability to Learn Fast WORK EXPERIENCE BusinessDay Media Ltd Business Development Executive BusinessDay Training Responsibilities July 2014- May 2015 Preparation of annual training calendar Marketing training programmes to clients Preparation of training advertisement in the newspaper and online Research into training needs of clients Planning and organizing trainings and workshops Managing the social media platforms, website information. Preparation of management report BusinessDay Media Limited. Feb- July 2014 Head, Youth Segment/Campus Sales Responsibilities Engagement of stakeholders in all tertiary institutions Monitoring, co-ordination, and supervision of all campus sales’ executive nationwide Securing regular subscription for the newspaper Initiating/organizing students’ oriented programmes/projects Collation of reports for weekly management meeting Guaranty Trust Bank Plc, International Airport Road, Lagos 2012-2014 Transaction Officer Responsibilities Customer Relationship Identifying New Market for -

Spatial Variations of Values of Residential Land Use in Lagos Metropolis (Pp

An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 3 (2), January, 2009 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Spatial Variations of Values of Residential Land Use in Lagos Metropolis (Pp. 381-403) Leke Oduwaye -Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Lagos, Akoka, Lagos. [email protected] ; [email protected] Abstract The cost of land has very strong influence on the quality and type of development that can be sustained on such land. Residential areas are no exception. This is more pronounced in economically vibrant. Lagos being the economic nerve centre of Nigeria fall into this category cities. This study is therefore to further enrich existing literature in this area but focusing on residential land values in Metropolitan Lagos. In the study, the actual prices of various components of residential land use are established which the study classified into rent, purchase price of residential apartments and purchase price of residential plots of land. This was done for different residential land use types which the study classified into three: namely high density, medium density and low density areas. The study concludes that residential land values are high in the low density areas and lower at the high density areas. The paper suggests the need to improve both physical and economic access to residential properties, privatization of the supply of infrastructural facilities, improvement in the quality of the environment and the need to release lands under public ownership to make more land available for residential use. Keywords: Residential, Land Value, Neighbourhood, Rent, Cost, Land. Copyright: IAARR, 2009 www.afrrevjo.com 381 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info African Research Review Vol. -

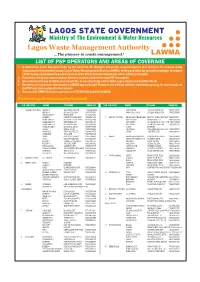

List of Psp Operators and Areas of Coverage 1

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT Ministry of The Environment & Water Resources Lagos Waste Management Authority ...The pioneer in waste management! LAWMA LIST OF PSP OPERATORS AND AREAS OF COVERAGE 1. In furtherance of the Executive Order by the Governor, Mr. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, on government's zero tolerance for reckless waste disposal and environmental abuse, Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA), hereby publishes for general knowledge, the names of PSP operators mandated to provide services in the 20 Local Government Areas and 37 LCDAs in the state. 2. Remember to bag your wastes and put them in covered containers for easy PSP evacuation. 3. Also endeavour to pay promptly your waste bills, as we collectively work to make Lagos cleaner and healthier for all. 4. Residents are enjoined to download the LAWMA app on Google Playstore and visit our website, www.lawma.gov.ng, for more details on the PSP operators assigned to their streets. 5. You can call LAWMA for back up services on 07080601020 and 08034242660. #ForAGreaterLagos #KeepLagosClean #PayYourWastebill S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO 1 AGBADO OKE ODO ABORU I GOFERMC NIG LTD "08038498764 OMITUNTUN IYALAJE WASTE CO. "08073171697 ABORU II MOJAK GOLD ENT "08037163824 SANTOS/ILUPEJU GOLDEN RISEN SUN "08052323909 ABULE EGBA II FUMAB ENT "08164147462 AGBADO CHRISTOCLEAR VENT "08058461400 7 AMUWO ODOFIN ABULE ADO/TRADE FAIR NEXT TO GODLINESS ENT "08033079011 AGBELEKALE I ULTIMATE STEVE VENT "08185827493 ADO FESTAC DOMOK NIG LTD "08053939988 AGBELEKALE II KHARZIBAB ENT "08037056184 EKO AKETE OLUWASEUN INV. COY LTD "08037139327 AGBELEKALE III METROPOLITAN "08153000880 IFELODUN GLORIOUS RISE ENT "08055263195 AGBULE EGBA I WOTLEE & SONS "08087718998 ILADO RIVERINE AJASA BOIISE TRUST "08023306676 IREPODUN CARLYDINE INV. -

“The Poor Also Must Live!” Market Demolition, Gentrification and the Quest for Survival in Lagos State

“The Poor Also Must Live!” Market Demolition, Gentrification and the Quest for Survival in Lagos State. October 2016 “The Poor Also Must Live!” Market Demolition, Gentrification and the Quest for Survival in Lagos State. Author: Gbenga Komolafe, General Secretary, Federation of Informal Workers' Organizations of Nigeria (FIWON) Publication Date: October 2016 About FIWON: FIWON is a membership based organization of self - employed workers in the informal sectors of the Nigerian economy. Whereas workers in the informal sectors constitute over 80% of non-agricultural employment, 60% of the urban employment and over 90% of new jobs in Nigeria, they are often subjected to arbitrary and excessive taxation, downright extortion, arbitrary arrests and imprisonment while their basic needs for social security is ignored. Informal workers constitute the bulk of the poor and marginalized people in Nigeria. FIWON was inaugurated June 18, 2010 in Abuja in the course of its 1st National Conference in Abuja with over 34 self - employed workers’ organizations in attendance. Today, there are over 120 organizations from 15 states of the Nigerian federation. FIWON’s overall goal is to transform the working and living conditions of informal workers to an acceptable standard that guarantees their basic human rights as citizens and workers. FIWON builds leadership capacities of informal workers for resisting rights violation and for representation in decision making public institutions. It has a Cooperative and Thrift arm that provide soft loans for members while it collaborates with public and private institutions for vocational and entrepreneurial training of members. “The Poor Also Must Live!” Market Demolition, Gentrification and the Quest for Survival in Lagos State. -

Groundwater Quality Assessment in Eti-Osa, Lagos-Nigeria Using Multivariate Analysis

J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manage. March , 2011 JASEM ISSN 1119-8362 Full-text Available Online at All rights reserved www.bioline.org.br/ja Vol. 15 (1) 121 - 125 Groundwater Quality Assessment in Eti-Osa, Lagos-Nigeria using Multivariate Analysis *AKOTEYON, I S; SOLADOYE, O Department of Geography and Planning, Lagos State University, Ojo, Lagos-Nigeria ABSTRACT: Groundwater quality in Eti-Osa was assessed . 18 water samples were collected from hand dug well and measured for 3 physical (pH, EC and TDS) and 9 chemical parameters (Ca, Cl, Fe, TH, Mg, NO 3, SO 4,TSS and Zn) after standard procedures (APHA). The results show that pH of groundwater samples indicates a neutral condition (7.01).TH was slightly hard (37.11mg/l).TDS, Fe and Mg concentrations were above the NDWQS limit of (500, 0.3 and 0.2mg/l) respectively for drinking water purpose. The Coefficient of variation shows that all the groundwater parameters with the exception of pH, Ca, Cl and Fe are highly heterogeneous. The correlation among the groundwater parameters shows that pH has a negative correlation at with Ca and TSS (r= -0.49).TH and Ca showed a positive correlations with Cl (r=0.51), EC (r=0.58).The factor analysis employed indicates four factors. Factor I, explains 27.73% of the total variance, with a strong positive loading on EC, TDS, Ca and a negative loading on pH. Factor II accounts for 21.35% of the total variance, and was characterized by strong positive loading of Zn and negative loading of Fe and TDS.Factor III was characterized by high positive loading of Cl and TH and accounts for 15.98% of the total variance while factor IV accounts for 14.05% of the total variance and was characterized by a strong positive loading of NO 3.The paper recommended routine monitoring and thorough treatment before consumption. -

LGA LCDA List of Roads Length Pavement Agege 1A JJ Oba Remo Road,Agege Ajakaye/Arigidi/Elicana 718 Asphaltic Concrete

LGA LCDA List of Roads Length Pavement Agege 1a JJ Oba Remo road,Agege Ajakaye/Arigidi/Elicana 718 Asphaltic Concrete Awori/Adesokan 820 Asphaltic Concrete Orile Agege Igbayilola/Kusoro/Olabode Olaiya Road 864 Asphaltic Concrete ILogbe street 562 Interlocking pavement stone Ajeromi - Ifelodun Ajeromi Uzor street 790 Interlocking pavement stone Akogun road 680 Interlocking pavement stone Ifelodun Adekoya/Owoyemi street 930 Interlocking pavement stone Adejiyan street 565 Interlocking pavement stone Alimosho Alimosho Jimoh Akinremi/Ogunbiyi street 947 Asphaltic Concrete Olarewaju/Soyombo Alaka street 563 Asphaltic Concrete Olawale cole 395 Asphaltic Concrete Oki Road 650 Asphaltic Concrete Ayobo Ipaja Baba Kaka street 935 Asphaltic Concrete Yusuf street 603 Asphaltic Concrete Egbe Idimu Community road,Agodo 822 Asphaltic Concrete Oduwole street 810 Asphaltic Concrete Igando Ikotun Tanimowo/Oladepo/Abibatu 762 Asphaltic Concrete Rufia Ashimi/Abuba Anthony street 746 Asphaltic Concrete Mosan Okunola Awori street Akinogun 302 Asphaltic Concrete 1st Avenue Abesan Estate 513 Asphaltic Concrete Amowo-Odofin Amowo odofin Agidimo Road Jakande Estate 360 Interlocking pavement stone 512 Road Festac Town 700 Interlocking pavement stone Oriade Omila Street,Onireke Barrack 955 Interlocking pavement stone Ade Oshodi Street 685 Interlocking pavement stone Apapa Apapa Itapeju/mushin Road 400 Asphaltic Concrete Payne Crescent/Oniru 680 Asphaltic Concrete Iganmu Akosile street off Gaskiya 364 Asphaltic Concrete Sadiku/Oluwatoyin/Ajagbe/adunni 850 Asphaltic -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 49974-NG PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED CREDIT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 119.6 MILLION (US$190.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) AND A PROPOSED TRUST FUND GRANT FROM THE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY IN THE AMOUNT OF US$4.5 MILLION TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA FOR THE LAGOS URBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT 2 JUNE 2, 2010 Transport Sector Country Department AFCW2 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective October 30, 2009) Currency Unit = Nigerian Naira US$1 = 151 Nigerian Naira US$1 = SDR 0.6289 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFD Agence Française de Développement (French Development Agency) BCR Benefit-Cost Ratio BPP Bureau of Public Procurement BRT Bus Rapid Transit CAS Country Assistance Strategy CBO Community Based Organizations CEO Chief Executive Officer CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment CMS Church Missionary Society CO Carbon Monoxide CO2 Carbon Dioxide CBD Central Business District CPAR Country Procurement Assessment Review CPS Country Partnership Strategy CQS Consultants’ Qualifications Selection CRM Customer Relationship Management DA Designated Account DfID United Kingdom Department for International Development -

S/N Bdc Name Address State 1 1 Hr Bdc Ltd Suite 24, 2Nd

FINANCIAL POLICY AND REGULATION DEPARTMENT CONFIRMED BUREAUX DE CHANGE IN COMPLIANCE WITH NEW REQUIREMENTS AS AT JULY 31, 2014 S/N BDC NAME ADDRESS STATE 1 1 HR BDC LTD SUITE 24, 2ND FLOOR, KINGSWAY BUILDING, 51/52 MARINA, LAGOS LAGOS 2 19TH BDC LTD 105 ZOO ROAD, GIDAN DAN ASABE KANO 3 313 BDC LTD SUITE 5, ZONE 4 PLAZA, PLOT 2249, ADDIS ABABA CRESCENT, WUSE, ABUJA ABUJA 4 3D SCANNERS BDC LTD 2ND FLOOR, UNION ASSURANCE TOWER, 95 BROAD STREET, LAGOS LAGOS 5 6JS BDC LTD BLUECREST MALL,SUITE 51 KM43,LEKKI EPE EXPRESSWAY LAGOS PLOT 1663, BIG LEAF HOUSE, 6TH FLOOR, OYIN JOLAYEMI STREET, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS OLD ADDRESS: INVESTMENT 6 8-TWENTY FOUR BDC LTD HOUSE, 8TH FLOOR, 21/25, BROAD STREET, LAGOS LAGOS 7 A & C BDC LTD BLOCK 9, SHOP 1/2, AGRIC MARKET, COKER, LAGOS LAGOS 16, ABAYOMI ADEWALE STREET, AGO PALACE WAY, OKOTA, ISOLO OR SUITE 122, BLOCK A2, 104 SURA SHOPPING COMPLEX, 8 A & S BDC LTD SIMPSON ST. LAGOS LAGOS 9 A A S MARMARO BDC LTD LAGOS ISLAND LAGOS 10 A AND B BDC LTD 12, UNITY ROAD, KANO KANO 11 A THREE BDC LTD NO. 77 OPP NNPC HOTORO, KANO KANO 12 A. W. Y. BDC LTD 10, BAYAJIDDA- LEBANON ROAD, KWARI MARKET, KANO OR 1, LEBANON ROAD, KWARI MARKET, KANO KANO 13 A.A. LUKORO BDC LTD 59, YANNONO LINE, KWARI MARKET, FAGGE, TAKUDU, KANO KANO 14 A.A. SILLA BDC LTD 4, SANNI ADEWALE STREET, 2ND FLOOR, LAGOS ISLAND LAGOS 15 A.A.RANO BDC LTD NO. -

Ikioda, Faith.Pdf

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Faith Ikioda Thesis title: Limits to Communities of Practise in an Open Air Market - The Case of the Alaba-Suru Market, Lagos, Nigeria Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. This thesis was embargoed until June 2012. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Limits to Communities of Practice in an Open Air Market -The Case of the Alaba-Suru Market,Lagos,Nigeria Faith Osikwheme Ikioda Department of Geography University of Sheffield May 2012 Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Since its introduction into the literature over ten years ago, the concept of the community of practice has been prolifically employed in a range of different disciplines. A community of practice is regarded as denoting a set of relations through which a group of actors mutually learn and share knowledge in order to produce innovative outcomes in a particular activity. Many authors who have adopted the term have however primarily restricted evidence of such communities to very formally organised contexts that are characterised by relatively homogenous and collaborative events. This thesis therefore examines the activities among market traders in an open-air market and seeks to understand whether evidence of a community of practice can be found in settings that are characterised by actors involved in self-employment and competitive contexts as opposed to the previous contexts that have shaped evidence of the community of practice. -

Lagos Town Council

B 185 Supplement to Official Gazette No. 56, Vol. 47, 15th September, 1960—Part B L.N. 141 of 1960 Order made under THE ROAD TRAFFIC ORDINANCE (CAP. 184 OF THE LAWS OF NIGERIA) Commencement : 15th September, 1960 _ Inexercise of the powers conferred by-section 11 of the Road Traffic Ordinance, the following Order is hereby made by the Lagos Town Council. 1, (¢) This Order may be cited as the Road Traffic (Control of Traffic) Short title (Lagos) Order, 1960. and application. '* (@) This Order applies to the Town of Lagos. 2. The Road Traffic (Control of Traffic) (Lagos) Order 1959 published in _ Revocation the Federation of Nigeria Official Gazette as Legal Notice No. 143 of 1959 of Road Trafic | is hereby revoked. (Controlof Traffic) — (Lagos) Order, 1959. 3. The use of the streets enumerated in the first column of the First Restriction _ Schedule is hereby restricted as specified in the second column of the of use of Highways. Schedule. : 4, The driving or propelling ofvehicles in any of the streets specified in One-way the first column of the Second Schedule is hereby prohibited otherwise than streets. in the directions specified in the second columnof the Schedule. 5. Vehicles other than suburban buses intending to wait along thestreets Parking of shownin the first column of the Third Schedule may be parked only on the waiting. sides of the streets and or on the days specified in the second column of the Schedule. 6. The stopping places for suburban, non-suburban, school children’s Stopping buses and Stage Carriages shall be as specified in the Fourth Schedule.