A New Mother's Buddhist Journey Through Death, Grief and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Continuity and Change in Early Baptist Perceptions on the Church and Its Mission.” Dr

0 Vol. 5 · No. 1 Spring 2008 Baptists on Mission 3 Editorial Introduction: Baptists On Mission Dr. Steve W. Lemke Editor-in-Chief Section 1: North American Missions Dr. Charles S. Kelley & Church Planting Executive Editor 9 Ad Fontes Baptists? Continuity and Change in Early Dr. Steve W. Lemke Baptist Perceptions on the Church and Its Mission Dr. Philip Roberts Book Review Editors Dr. Page Brooks The Emerging Missional Churches of the West: Form Dr. Archie England 17 Dr. Dennis Phelps or Norm for Baptist Ecclesiology? Dr. Rodrick Durst BCTM Founder Dr. R. Stanton Norman 31 The Mission of the Church as the Mark of the Church Dr. John Hammett Assistant Editor Christopher Black An Examination of Tentmaker Ministers in Missouri: 41 BCTM Fellow & Layout Challenges and Opportunities Rhyne Putman Drs. David Whitlock, Mick Arnold, and R. Barry Ellis Contact the Director 53 The Way of the Disciple in Church Planting [email protected] Dr. Jack Allen 1 2 JBTM Vol. 5 · no. 1 spring 2008 67 Ecclesiological Guidelines to Inform Southern Baptist Church Planters Dr. R. Stanton Norman Section 2: International Missions 93 The Definition of A Church International Mission Board 95 The Priority of Incarnational Missions: Or “Is The Tail of Volunteerism Wagging the Dog?” Dr. Stan May 103 Towards Practice in Better Short Term Missions Dr. Bob Garrett 121 The Extent of Orality Dr. Grant Lovejoy 135 The Truth is Contextualization Can Lead to Syncretism: Applying Muslim Background Believers Contextualization Concerns to Ancestor Worship and Buddhist Background Believers in a Chinese Culture Dr. Phillip A. Pinckard 143 Addressing Islamic Teaching About Christianity Dr. -

5 Days in HK

5 days in HK Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] 5 days in HK Our Hong Kong trip plan. Full day by day travel plan for our summer vacaon in Hong Kong. It is hard to visualize unless you’ve been there and experienced the energy that envelops the enre country. Every corner of Hong Kong has something to discover, here are the top aracons and things to do in Hong Kong to consider, our China travel guide. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak 1. Hong Kong Park 4. Victoria Peak Duration ~ 2 Hours Duration ~ 1 Hour Mid-level, Hong Kong Victoria Peak, The Peak, Hong Kong Rating: 4.5 Start the day off with an invigorang walk through Hong Kong Park, admiring fountains, landscaping, and even an At the summit, incredible visuals await—especially around aviary before heading towards the Peak Tram, which takes sunset. you to the top of the famous Victoria Peak. WIKIPEDIA Victoria Peak is a mountain in the western half of Hong Kong 2. Hong Kong Zoological And Botanical Gardens Island. It is also known as Mount Ausn, and locally as The Duration ~ 1 Hour Peak. With an elevaon of 552 m, it is the highest mountain on Hong Kong island, ranked 31 in terms of elevaon in the Hong Kong Hong Kong Special Administrave Region. The summit is Rating: 2.9 more.. Nearby the peak Tram Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, a free aracon, is also not even 5 minutes away from the Peak Tram. -

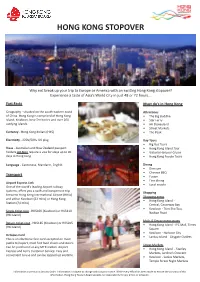

Hong Kong Stopover

HONG KONG STOPOVER Why not break up your trip to Europe or America with an exciting Hong Kong stopover? Experience a taste of Asia’s World City in just 48 or 72 hours... Fast Facts Must do’s in Hong Kong Geography - situated on the south-eastern coast Attractions of China. Hong Kong is comprised of Hong Kong • The Big Buddha Island, Kowloon, New Territories and over 260 • Star Ferry outlying islands. • HK Disneyland • Street Markets Currency - Hong Kong dollars (HK$) • The Peak Electricity - 220V/50Hz UK plug Day Tours • Big Bus Tours Visas - Australian and New Zealand passport • Hong Kong Island Tour holders DO NOT require a visa for stays up to 90 • Victoria Harbour Cruise days in Hong Kong • Hong Kong Foodie Tours Language - Cantonese, Mandarin, English Dining • Dim sum • Chinese BBQ Transport • Fusion • Fine dining Airport Express Link • Local snacks One of the world’s leading Airport railway systems, offers you a swift and inexpensive trip Shopping between Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) Shopping areas and either Kowloon (22 mins) or Hong Kong • Hong Kong Island - Station (24 mins) Central, Causeway Bay • Kowloon - Tsim Sha Tsui, Single ticket cost - HK$100 (Kowloon) or HK$110 Nathan Road (HK Island) Malls & Department stores Return ticket cost - HK$185 (Kowloon) or HK$205 • Hong Kong Island - IFC Mall, Times (HK Island) Square • Kowloon - Harbour City Octopus Card • Lantau Island - Citygate Outlets This is an electronic fare card accepted on most public transport, most fast food chains and stores. Street Markets Can be purchased at any MTR station, Airport • Hong Kong Island - Stanley Express and Ferry Customer Service. -

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

Ruthless Empire (Royal Elite Book 6)

RUTHLESS EMPIRE ROYAL ELITE BOOK SIX RINA KENT Ruthless Empire Copyright © 2020 by Rina Kent All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any other means without permission, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental. A L S O B Y R I N A K E N T ROYAL ELITE SERIES Cruel King Deviant King Steel Princess Twisted Kingdom Black Knight Vicious Prince Ruthless Empire LIES & TRUTHS DUET All The Lies All The Truths KINGDOM DUET Rule of a Kingdom (Free Prequel) Reign of a King Rise of a Queen TEAM ZERO SERIES Lured Crowed Ghosted Shadowed Misted Team Zero Boxset 1-3 THE RHODES SERIES Remorse (FREE) Ruin HATE & LOVE DUET He Hates Me He Hates Me Not To the divine, raw chaos inside you. A U T H O R N O T E Hello reader friend, Ruthless Empire marks the end of Royal Elite Series, and while there’s still an epilogue novella for all the characters, Cole and Silver’s book is the unofficial ending. Like you, this makes me so nostalgic and emotional. -

The Zen Studies Society

T H E N E W S L E T T E R O F THE ZEN STUDIES SOCIETY View of Mt. Fuji from Mt. Dai Bosatsu W I N T E R / S P R I N G 2006 Teisho on Rinzai Roku, The Book of Rinzai, Chapter 14 Eido T. Shimano Roshi 2 Dharma talk on Mumonkan, Gateless Gate Case 19 Roko ni-Osho Sherry Chayat 8 Dogyo-ninin (We Two Together) Shoshin Anne Hughes 13 Diary of Our Pilgrimage 2005 Seigan Ed Glassing 18 Dream? Fujin Zenni 25 My Impressions of the Pilgrimage to Japan Doshin David Schubert 26 Yamakawa Roshi performing Dai-Hannya View from inside the Genkan of Shogen-ji Our Trip October 2005 Yayoi Karen Matsumoto 27 Sesshin at Shogen-ji Saiun Atsumi Hara 29 Mandala Memories Banko Randy Phillips 31 Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji News 33 New York Zendo Shobo-ji News 36 Zen Studies Society News 37 Dai Bosatsu Zendo 2006 Calendar 39 New York Zendo 2006 Calendar 40 Published twice annually by The Zen Studies Society, Inc. Eido T. Shimano Roshi, Abbot Offices: New York Zendo Shobo-ji 223 East 67th Street New York, NY 10021-6087 Tel (212)861-3333 Fax 628-6968 offi[email protected] Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji 223 Beecher Lake Road Livingston Manor, NY 12758-6000 Tel (845)439-4566 Fax 439-3119 Roshi stands on top of Mount Dai Bosatsu offi[email protected] Editor: Seigan Edwin Glassing; News: Aiho-san Y. Shimano, Seigan Edwin Glassing, Fujin Zenni, Jokei Megumi Kairis; Graphic design:Banko Randy Phillips; Editorial Assistant and Proofreading: Myochi Nancy O’Hara; Teisho Transcription and Editing: Jimin Anna Klegon; Final Editing: Myochi Nancy O’Hara Photo Credits: Junsho Shelley Bello (pp. -

Copy of HK Tour Tariff 4

Adult USD86 Tour Ref.: T11-04 Child (3-11 yrs) USD70 360 Lantau Explorer Tour Duration: Approx. 7 hours Daily Morning Departure Hotel pick-up: Approx. 7:50am – 8:25am Lantau Island is one of the best-loved outlying islands in Hong Kong. With the new development of Ngong Ping Cable Car, and the opportunities to see a unique sub-species of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin, the Island has become a new attraction in Hong Kong. Get close to nature on this tour and explore Tai O, a quaint fishing village where the houses are on stilts, visit the World’s tallest outdoor, seated bronze Buddha statue at the Po Lin Monastery and enjoy a great vegetarian meal there. Cruise Ride on the South China Sea and Dolphin Watching Tour starts with a cruise ride on the South China Sea to see certain outlying islands of Hong Kong and a close-up view on flight departure from Hong Kong International Airport. If you are lucky enough, you can even see the pink dolphins, a unique sub-species of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin and are known-and loved-for their pink colour. They are also the official mascot of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Tai O Fishing Village Tai O, also known as the “Venice of the East” was once the largest inhabited settlement on Lantau Island. The village’s stilt houses on the waterfront, offer a glimpse into Hong Kong’s past and provide a striking contrast with the modern city. Po Lin Monastery Po Lin Monastery is the most popular Buddhist temple in Hong Kong. -

S 0620 State of Rhode Island

2017 -- S 0620 ======== LC002208 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2017 ____________ S E N A T E R E S O L U T I O N CONGRATULATING RHODE ISLAND NATIVE BILLY GILMAN ON HIS SINGING CAREER AND FINISHING AS RUNNER-UP ON THE VOICE Introduced By: Senators Morgan, Algiere, Kettle, Gee, and Paolino Date Introduced: March 16, 2017 Referred To: Recommended for Immediate Consideration 1 WHEREAS, William Wendell Gilman, III, known professionally as "Billy Gilman", was 2 born on May 24, 1988, in Westerly, Rhode Island, the son of Frances "Fran" Woodmansee and 3 William Wendell Gilman, Jr. Billy was raised in the Town of Richmond along with his younger 4 brother Colin; and 5 WHEREAS, Billy was a precocious youngster who loved singing from an early age. As a 6 toddler, Billy would sing for friends and family using his toy karaoke machine, wowing them 7 with his incredible voice and natural ability. By the age of 5, Billy would delight in shopping with 8 his mom at a Westerly supermarket, and would stick his head inside the door of a frozen food 9 case, and sing to see if the echo would make him sound like he was on a stage. He liked what he 10 heard and he scribbled on the condensation of the glass door the words, "Now Starring: Billy 11 Gilman!"; and 12 WHEREAS, Billy gave his first public performance on a stage at the age of seven. Billy 13 Gilman later performed at the Washington County Fair in Richmond and other local fairgrounds 14 in the New England area. -

Religion in the Age of Development

religions Article Religion in the Age of Development R. Michael Feener 1,* and Philip Fountain 2 1 Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, Marston Road, Oxford OX3 0EE, UK 2 Religious Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington 6140, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 20 November 2018; Published: 23 November 2018 Abstract: Religion has been profoundly reconfigured in the age of development. Over the past half century, we can trace broad transformations in the understandings and experiences of religion across traditions in communities in many parts of the world. In this paper, we delineate some of the specific ways in which ‘religion’ and ‘development’ interact and mutually inform each other with reference to case studies from Buddhist Thailand and Muslim Indonesia. These non-Christian cases from traditions outside contexts of major western nations provide windows on a complex, global history that considerably complicates what have come to be established narratives privileging the agency of major institutional players in the United States and the United Kingdom. In this way we seek to move discussions toward more conceptual and comparative reflections that can facilitate better understandings of the implications of contemporary entanglements of religion and development. Keywords: Religion; Development; Humanitarianism; Buddhism; Islam; Southeast Asia A Sarvodaya Shramadana work camp has proved to be the most effective means of destroying the inertia of any moribund village community and of evoking appreciation of its own inherent strength and directing it towards the objective of improving its own conditions. A.T. -

Spire Light Spire Light

Spire Light Spire Light Spire Light A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 2021 2 0 2 1 Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 Copyright © 2021 by Andrew College All rights reserved. This book or any portion may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review or scholarly journal. ISBN: 978-1-6780-6324-5 Andrew College 501 College Street Cuthbert, GA 39840 www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Cover Art: "Small Things," Chris Johnson Cover Design by Heather Bradley Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief Penny Dearmin Art Editor Noah Varsalona Fiction Editors Kenyaly Quevedo Jermaine Glover Poetry Editor Hasani “Vibez” Comer Creative Nonfiction Editor Penny Dearmin Assistant Layout Editor Cameron Cabarrus www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Editor's Notes Penny Dearmin Editor-in-Chief To produce or curate art in this time is an act of service—to ourselves and the world who all need to believe again. We decided to say yes when there is a no at every corner. Yes, we will have our very first contest for the Illumination Prose Prize. Yes, we will accept an ekphrasis prose poem collaboration. Rather than place limits with a themed call for submissions, we did our best to remain open. These pieces should carry you to the hypothetical, a place where there are possibilities to unsee what you think you know. Isn’t that what we have done this year? Escaped? You can be grounded, too. -

American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter

CHAPTER FO U R American Buddhists: Enlightenment and Encounter ★ he Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated for weeks on end in Los Angeles. TMore than three hundred Buddhist temples sit in this great city fac- ing the Pacific, and every weekend for most of the month of May the Buddha’s Birthday is observed somewhere, by some group—the Viet- namese at a community college in Orange County, the Japanese at their temples in central Los Angeles, the pan-Buddhist Sangha Council at a Korean temple in downtown L.A. My introduction to the Buddha’s Birthday observance was at Hsi Lai Temple in Hacienda Heights, just east of Los Angeles. It is said to be the largest Buddhist temple in the Western hemisphere, built by Chinese Buddhists hailing originally from Taiwan and advocating a progressive Humanistic Buddhism dedicated to the pos- itive transformation of the world. In an upscale Los Angeles suburb with its malls, doughnut shops, and gas stations, I was about to pull over and ask for directions when the road curved up a hill, and suddenly there it was— an opulent red and gold cluster of sloping tile rooftops like a radiant vision from another world, completely dominating the vista. The ornamental gateway read “International Buddhist Progress Society,” the name under which the temple is incorporated, and I gazed up in amazement. This was in 1991, and I had never seen anything like it in America. The entrance took me first into the Bodhisattva Hall of gilded images and rich lacquerwork, where five of the great bodhisattvas of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition receive the prayers of the faithful.