Hong Kong, 7 – 12 December 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Days in HK

5 days in HK Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] 5 days in HK Our Hong Kong trip plan. Full day by day travel plan for our summer vacaon in Hong Kong. It is hard to visualize unless you’ve been there and experienced the energy that envelops the enre country. Every corner of Hong Kong has something to discover, here are the top aracons and things to do in Hong Kong to consider, our China travel guide. Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak Contact us | turipo.com | [email protected] Day 1 - Hong Kong Park & Victoria Peak 1. Hong Kong Park 4. Victoria Peak Duration ~ 2 Hours Duration ~ 1 Hour Mid-level, Hong Kong Victoria Peak, The Peak, Hong Kong Rating: 4.5 Start the day off with an invigorang walk through Hong Kong Park, admiring fountains, landscaping, and even an At the summit, incredible visuals await—especially around aviary before heading towards the Peak Tram, which takes sunset. you to the top of the famous Victoria Peak. WIKIPEDIA Victoria Peak is a mountain in the western half of Hong Kong 2. Hong Kong Zoological And Botanical Gardens Island. It is also known as Mount Ausn, and locally as The Duration ~ 1 Hour Peak. With an elevaon of 552 m, it is the highest mountain on Hong Kong island, ranked 31 in terms of elevaon in the Hong Kong Hong Kong Special Administrave Region. The summit is Rating: 2.9 more.. Nearby the peak Tram Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, a free aracon, is also not even 5 minutes away from the Peak Tram. -

Hong Kong Stopover

HONG KONG STOPOVER Why not break up your trip to Europe or America with an exciting Hong Kong stopover? Experience a taste of Asia’s World City in just 48 or 72 hours... Fast Facts Must do’s in Hong Kong Geography - situated on the south-eastern coast Attractions of China. Hong Kong is comprised of Hong Kong • The Big Buddha Island, Kowloon, New Territories and over 260 • Star Ferry outlying islands. • HK Disneyland • Street Markets Currency - Hong Kong dollars (HK$) • The Peak Electricity - 220V/50Hz UK plug Day Tours • Big Bus Tours Visas - Australian and New Zealand passport • Hong Kong Island Tour holders DO NOT require a visa for stays up to 90 • Victoria Harbour Cruise days in Hong Kong • Hong Kong Foodie Tours Language - Cantonese, Mandarin, English Dining • Dim sum • Chinese BBQ Transport • Fusion • Fine dining Airport Express Link • Local snacks One of the world’s leading Airport railway systems, offers you a swift and inexpensive trip Shopping between Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) Shopping areas and either Kowloon (22 mins) or Hong Kong • Hong Kong Island - Station (24 mins) Central, Causeway Bay • Kowloon - Tsim Sha Tsui, Single ticket cost - HK$100 (Kowloon) or HK$110 Nathan Road (HK Island) Malls & Department stores Return ticket cost - HK$185 (Kowloon) or HK$205 • Hong Kong Island - IFC Mall, Times (HK Island) Square • Kowloon - Harbour City Octopus Card • Lantau Island - Citygate Outlets This is an electronic fare card accepted on most public transport, most fast food chains and stores. Street Markets Can be purchased at any MTR station, Airport • Hong Kong Island - Stanley Express and Ferry Customer Service. -

Egn201014152134.Ps, Page 29 @ Preflight ( MA-15-6363.Indd )

G.N. 2134 ELECTORAL AFFAIRS COMMISSION (ELECTORAL PROCEDURE) (LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL) REGULATION (Section 28 of the Regulation) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BY-ELECTION NOTICE OF DESIGNATION OF POLLING STATIONS AND COUNTING STATIONS Date of By-election: 16 May 2010 Notice is hereby given that the following places are designated to be used as polling stations and counting stations for the Legislative Council By-election to be held on 16 May 2010 for conducting a poll and counting the votes cast in respect of the geographical constituencies named below: Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency LC1 A0101 Joint Professional Centre Hong Kong Island Unit 1, G/F., The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong A0102 Hong Kong Park Sports Centre 29 Cotton Tree Drive, Central, Hong Kong A0201 Raimondi College 2 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0301 Ying Wa Girls' School 76 Robinson Road, Mid Levels, Hong Kong A0401 St. Joseph's College 7 Kennedy Road, Central, Hong Kong A0402 German Swiss International School 11 Guildford Road, The Peak, Hong Kong A0601 HKYWCA Western District Integrated Social Service Centre Flat A, 1/F, Block 1, Centenary Mansion, 9-15 Victoria Road, Western District, Hong Kong A0701 Smithfield Sports Centre 4/F, Smithfield Municipal Services Building, 12K Smithfield, Kennedy Town, Hong Kong Code and Name of Polling Station Geographical Place designated as Polling Station and Counting Station Code Constituency A0801 Kennedy Town Community Complex (Multi-purpose -

Copy of HK Tour Tariff 4

Adult USD86 Tour Ref.: T11-04 Child (3-11 yrs) USD70 360 Lantau Explorer Tour Duration: Approx. 7 hours Daily Morning Departure Hotel pick-up: Approx. 7:50am – 8:25am Lantau Island is one of the best-loved outlying islands in Hong Kong. With the new development of Ngong Ping Cable Car, and the opportunities to see a unique sub-species of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin, the Island has become a new attraction in Hong Kong. Get close to nature on this tour and explore Tai O, a quaint fishing village where the houses are on stilts, visit the World’s tallest outdoor, seated bronze Buddha statue at the Po Lin Monastery and enjoy a great vegetarian meal there. Cruise Ride on the South China Sea and Dolphin Watching Tour starts with a cruise ride on the South China Sea to see certain outlying islands of Hong Kong and a close-up view on flight departure from Hong Kong International Airport. If you are lucky enough, you can even see the pink dolphins, a unique sub-species of the Indo-Pacific Humpback Dolphin and are known-and loved-for their pink colour. They are also the official mascot of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Tai O Fishing Village Tai O, also known as the “Venice of the East” was once the largest inhabited settlement on Lantau Island. The village’s stilt houses on the waterfront, offer a glimpse into Hong Kong’s past and provide a striking contrast with the modern city. Po Lin Monastery Po Lin Monastery is the most popular Buddhist temple in Hong Kong. -

Register of Public Payphone

Register of Public Payphone Operator Kiosk ID Street Locality District Region HGC HCL-0007 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0010 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HGC HCL-0024 Des Voeux Road Central Outside Wheelock House Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2338 Caine Road Outside Albron Court Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1488 Caine Road Outside Ho Shing House, near Central - Mid-Levels Central and HK Escalators Western HKT HKT-1052 Caine Road Outside Long Mansion Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1090 Charter Garden Near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1042 Chater Road Outside St George's Building, near Exit F, MTR's Central Central and HK Station Western HKT HKT-1031 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1076 Chater Road Outside Statue Square Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1050 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Bus Stop Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1062 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1072 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Court of Final Appeal Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2321 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2322 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2323 Chater Road Outside Statue Square, near Prince's Building Central and HK Western HKT HKT-2337 Conduit Road Outside Elegant Garden Central and HK Western HKT HKT-1914 Connaught Road Central Outside Shun Tak -

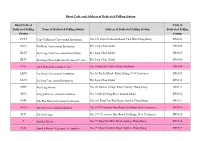

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station

Short Code and Address of Dedicated Polling Station Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station CCCI Cape Collinson Correctional Institution No. 123 Cape Collinson Road, Chai Wan, Hong Kong DPS101 NKCI Nei Kwu Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS104 HLCI Hei Ling Chau Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS105 HLTC Hei Ling Chau Addiction Treatment Centre Hei Ling Chau Island DPS106 LCK Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre No. 5 Butterfly Valley Road, Kowloon DPS108 LKCI Lai King Correctional Institution No. 16 Wa Tai Road, Kwai Chung, New Territories DPS109 LSCI Lai Sun Correctional Institution Hei Ling Chau Island DPS110 MHP Ma Hang Prison No. 40 Stanley Village Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS111 TFCI Tong Fuk Correctional Institution No. 31 Ma Po Ping Road, Lantau Island DPS112 PSW Pak Sha Wan Correctional Institution No. 101 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS113 PUCI Pik Uk Correctional Institution No. 399 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS114 PUP Pik Uk Prison No. 397 Clearwater Bay Road, Sai Kung, New Territories DPS115 S Stanley Prison No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS116 S(A) Stanley Prison (Category A Complex) No. 99 Tung Tau Wan Road, Stanley, Hong Kong DPS117 Short Code of Code of Dedicated Polling Name of Dedicated Polling Station Address of Dedicated Polling Station Dedicated Polling Station Station SLPC Siu Lam Psychiatric Centre No. 21 Hong Fai Road, Siu Lam, New Territories DPS118 SPP Shek Pik Prison No. 47 Shek Pik Reservoir Road, Lantau Island DPS119 STCI Sha Tsui Correctional Institution No. -

Po Lin Monastery and Big Buddha

#DMUglobal Hong Kong 2018 – Cultural Activities Po Lin Monastery and Big Buddha Dear Student, Thank you for booking a place onto the trip to the Po Lin Monastery and Big Buddha. We hope you are looking forward to one of Hong Kong’s top tourist spots. Your day will include the Ngong Ping Cable Car, which is a visually spectacular 5.7km cable car journey, travelling between Tung Chung Town Centre and Ngong Ping on Lantau Island. You will be greeted by stunning panoramic views of the Tian Tan Buddha Statue, South China Sea and beyond from a standard, crystal or private cabin. It is from Ngong Ping Village that you can take a short walk to the Po Lin Monastery and the Big Buddha for a full cultural experience. Please find below some important information regarding your activity. Date of activity: Saturday 24th March 2018 Meeting point: Tung Chung Cable Car Terminal Location: Ngong Ping Cable Car, 11 Tat Tung Rd, Lantau Island, Hong Kong Meeting time: 10.00am A representative from Study Trips (they will be signposted) will meet you at the meeting point at the above times with your cable car ticket. What you need to do You will need to make your own way to the Ngong Ping Cable Car. It will take approximately 30 minutes to get there (via the MTR system) Recommended time to leave your hotel is 09.15 – 09.30am How to get there (all guides are based from the hotel) Use the MTR system – Link to trip planner (or download the MTR Mobile app) You will need to get the Tung Chung Line (Orange) End station is Tung Chung Station Please click here for further direction guides to help you If you have any questions regarding the Cultural Activity for the Po Lin Monastery and Big Buddha, please email [email protected] or call us on 0116 257 7613. -

Driving Services Section

DRIVING SERVICES SECTION Taxi Written Test - Part B (Location Question Booklet) Note: This pamphlet is for reference only and has no legal authority. The Driving Services Section of Transport Department may amend any part of its contents at any time as required without giving any notice. Location (Que stion) Place (Answer) Location (Question) Place (Answer) 1. Aberdeen Centre Nam Ning Street 19. Dah Sing Financial Wan Chai Centre 2. Allied Kajima Building Wan Chai 20. Duke of Windsor Social Wan Chai Service Building 3. Argyle Centre Nathan Road 21. East Ocean Centre Tsim Sha Tsui 4. Houston Centre Mody Road 22. Eastern Harbour Centre Quarry Bay 5. Cable TV Tower Tsuen Wan 23. Energy Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 6. Caroline Centre Ca useway Bay 24. Entertainment Building Central 7. C.C. Wu Building Wan Chai 25. Eton Tower Causeway Bay 8. Central Building Pedder Street 26. Fo Tan Railway House Lok King Street 9. Cheung Kong Center Central 27. Fortress Tower King's Road 10. China Hong Kong City Tsim Sha Tsui 28. Ginza Square Yau Ma Tei 11. China Overseas Wan Chai 29. Grand Millennium Plaza Sheung Wan Building 12. Chinachem Exchange Quarry Bay 30. Hilton Plaza Sha Tin Square 13. Chow Tai Fook Centre Mong Kok 31. HKPC Buil ding Kowloon Tong 14. Prince ’s Building Chater Road 32. i Square Tsim Sha Tsui 15. Clothing Industry Lai King Hill Road 33. Kowloonbay Trademart Drive Training Authority Lai International Trade & King Training Centre Exhibition Centre 16. CNT Tower Wan Chai 34. Hong Kong Plaza Sai Wan 17. Concordia Plaza Tsim Sha Tsui 35. -

Hong Kong Lantau Po Lin Monastery Tour

Hong Kong Lantau Po Lin Monastery Tour HIGHLIGHTS ITINERARY Duration Half Day app. 4 hours The tour begins by air-conditioned coach pick up from hotel to Tung Chung, a newly developed town on Lantau Island. Approximately 25 minute’s cable car ride from Tung Chung to Ngong Ping Plateau (520-metre-high) offering stunning views. Stroll through the culturally themed Ngong Ping Village, then comes to the Great Bronze Buddha Statue, at 26 meters tall and 202 tones; it is the world’s tallest, outdoor, seated, bronze statue of Buddha. Adjacent to the statue is Po Lin Monastery (Precious Lotus), founded by three monks in 1920 as a monastic retreat. Today it is a major religious enterprise, blessed with brightly decorated temples and floral garden. A short walk away is the Wisdom Path where an ancient prayer is inscribed on a series of wooden columns set in a figure of eight to signify infinity. One column is left blank to suggest the concept of emptiness, a key theme in the prayer. Taking the cable car from Ngong Ping back to Tung Chung At around 14:00, the return trip to hotel from Tung Chung by coach QUOTATION Number of Pax Net Rates per person (USD) 1 pax 475 2-5 pax 265 6-9 pax 200 10-15 pax 135 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION What's Included What's Not Included All overland private transfers with English International & domestic flights and relevant speaking guide. taxes All admission fees and activity expenses, as Hong Kong tourist visa, which is required for noted in the itinerary most foreign passport holders Round trip Ngong Ping 360 ° Cable car Meals, excursions and activities not included ticket (standard class) in the itinerary Expenses of a personal nature,Discretionary gratuities for guides and chauffeurs NOTES OR FAQ’s The operation of this tour is subject to the weather condition and the operation of cable car. -

Draft South Lantau Coast Outline Zoning Plan No. S/Slc/20

Annex III of Paper No. IDC 56/2017 DRAFT SOUTH LANTAU COAST OUTLINE ZONING PLAN NO. S/SLC/20 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT DRAFT SOUTH LANTAU COAST OUTLINE ZONING PLAN NO. S/SLC/20 EXPLANATORY STATEMENT Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. AUTHORITY FOR THE PLAN AND PROCEDURE 1 3. OBJECT OF THE PLAN 2 4. NOTES OF THE PLAN 3 5. THE PLANNING SCHEME AREA 3 6. POPULATION 4 7. LAND USE ZONINGS 7.1 Residential (Group C) 4 7.2 Village Type Development 4 7.3 Government, Institution or Community 5 7.4 Other Specified Uses 5 7.5 Green Belt 6 7.6 Coastal Protection Area 6 7.7 Country Park 7 8. COMMUNICATIONS 7 9. UTILITY SERVICES 8 10. CULTURAL HERITAGE 8 11. IMPLEMENTATION 9 DRAFT SOUTH LANTAU COAST OUTLINE ZONING PLAN NO. S/SLC/20 (Being a Draft Plan for the Purposes of the Town Planning Ordinance) EXPLANATORY STATEMENT Note : For the purposes of the Town Planning Ordinance, this statement shall not be deemed to constitute a part of the Plan. 1. INTRODUCTION This Explanatory Statement is intended to assist an understanding of the draft South Lantau Coast Outline Zoning Plan (OZP) No. S/SLC/20. It reflects the planning intention and objectives of the Town Planning Board (the Board) for various land use zonings of the Plan. 2. AUTHORITY FOR THE PLAN AND PROCEDURE 2.1 Under the power delegated by the then Governor, the then Secretary for Planning, Environment and Lands directed the Board in June 1972, under section 3 of the Town Planning Ordinance (the Ordinance), to prepare a statutory plan for the main coastal strip of South Lantau. -

Ispl Consulting Limited

ISPL CONSULTING LIMITED Building Services, Energy, Commissioning and Mechanical Consultant Web: www.ISPL.com.hk E-mail: [email protected] updated: 05-10-2020 (09/20) Building Services – A&A Projects (total 294 nos.) Client Project Seniorman Design Limited 1. Architectural and Associated Consultancy Services Improvement Works for Yam Pak Building for Faculty of Engineering, The University of Hong Kong (NEW) Man Hing Hong Land 1. Chiller Plant Replacement for Pacific House, 20 Queen’s Investment Co., Ltd. / Road Central (NEW) Permanent Investment Co. 2. E&M Consultancy Services for Lift Replacement Work at Ltd. / Tsai Hing Co. Ltd. Parker House, No. 72 Queen’s Road Central (NEW) 3. E&M Consultancy Services for Lift Replacement Works (Carpark Lift No. 9) and Toilets Relocation at L2 & L3 at Man Yee Building, 60-68 Des Voeux Road (NEW) Arthur Yung and Associates 1. Proposed Residential Development, I.L. No. 5747, Blue Company Ltd. Pool Road M&E Consultancy Services for Show House Fitting Out Works Show Houses at 35A and 39B China Resources Logistics 1. E/M Consultancy Services for Replacement of Existing (Yuen Fat Wharf & Godown) Chiller Plant and Application of CLP’s Eco Building Fund Ltd. & Project Management of the Retrofitting Works at Yuen Fat Building, 89 Yen Chow Street West Kowloon (NEW) South Horizons Management 1. Chiller Replacement at Chiller Plant B and E, South Ltd. Horizons (NEW) Ho & Partners Architects 1. Consultancy Services Improvement Works for Haking Engineers & Development Wong Building, The University of Hong Kong (NEW) Consultants Limited AVT Design Architects Limited 1. Reinstatement of M&E Installation at Zung Fu Retail Network Page 1 of 23 Unit 2301, SUP Tower, 75 King’s Road, North Point, Hong Kong 香港北角英皇道 75 號聯合出版大廈 2301 室 Tel: 2797 9381 Fax: 2343 3132 ISPL CONSULTING LIMITED Building Services, Energy, Commissioning and Mechanical Consultant Web: www.ISPL.com.hk E-mail: [email protected] updated: 05-10-2020 (09/20) Building Services – A&A Projects (total 294 nos.) Client Project Hang Lung Real Estate Agency 1. -

Landac PC SC Paper No 04/2015

(Translated Version) For Discussion on LanDAC PC SC Paper 10 September 2015 No. 04/2015 Lantau Development Advisory Committee Planning and Conservation Subcommittee Overall Spatial Planning and Conservation Concepts for Lantau 1. Purpose 1.1 This paper aims at briefing Members on the Overall Spatial Planning and Conservation Concepts for Lantau (Planning and Conservation Concepts) (the study flow is at Plan 1) so as to inspire further discussion and comments by Members in paving the way for the formulation of the Overall Planning, Conservation, Economic and Social Development Strategy for Lantau (Development Strategy for Lantau). 2. Background 2.1 With reference to the baseline information, development opportunities and constraints analysis of Lantau previously reported to the Planning and Conservation Subcommittee and the strategic positioning, planning visions and directions etc. agreed upon by the Lantau Development Advisory Committee (LanDAC), together with the consideration of the planning background of Lantau, its latest developments and the overall strategic planning of Hong Kong, and the views from LanDAC members, its subcommittees and the public, the Planning Department (PlanD) has proposed the subject Planning and Conservation Concepts. The development potentials and considerations of Lantau and its overall strategic positioning, planning visions, directions and planning principles are summarised at Annexes 1 and 2. 2.2 The Planning and Conservation Concepts have considered the preliminary findings on the overall economic development of Lantau and the positioning of its four major commercial development areas from the on-going “Consolidated Economic Development Strategy for Lantau and Preliminary Market Positioning Study for Commercial Land Uses in Major Developments of Lantau” (Lantau Economic Development Strategy Study).