Asa Mudzimu RHODES UNIVERSITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Phd Thesis

Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Thesis committee Thesis supervisors Prof. dr. P. Richards Professor of Technology and Agrarian Development Wageningen University Prof. dr. K.E. Giller Professor of Plant Production Systems Wageningen University Thesis co-supervisor Dr. ir. C. J. M. Almekinders Assistant Professor, Technology and Agrarian Development Group Wageningen University Other members Prof. dr. ir. C. Leeuwis, Wageningen University Prof. dr. L.E. Visser, Wageningen University Dr. ir. K. F. Wiersum, Wageningen University Dr. B.B. Mukamuri, University of Zimbabwe This research was conducted under the auspices of the CERES Research School for Resource Studies for Development. Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M. J. Kropff in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 23 April 2010 at 11 a.m. in the Aula. Tendayi Mutimukuru-Maravanyika Can We Learn Our Way to Sustainable Management? Adaptive Collaborative Management in Mafungautsi State Forest, Zimbabwe. 231 pages Thesis Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2010) ISBN 978-90-8585-651-1 Dedication To my parents, my husband Simeon , my son Tafadzwa -

Census Results in Brief

116 Appendix 1a: Census Questionnaire 117 118 119 120 Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe 309 Gokwe North 702 Urban Areas Gokwe South 703 Marondera 321 Gweru Rural 704 Chivhu Town Board 322 Kwekwe Rural 705 Ruwa Local Board 323 Mberengwa 706 MASHONALAND WEST 4 Shurugwi 707 Rural Districts Zvishavane 708 Chegutu 401 Urban Areas Hurungwe 402 Gweru 721 Mhondoro-Ngezi 403 Kwekwe 722 Kariba 404 Redcliff 723 Makonde 405 Zvishavane 724 Gokwe Centre 725 . -

Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012

Zimbabwe Provincial Report Midlands ZIMBABWE POPULATION CENSUS 2012 Population Census Office P.O. Box CY342 Causeway Harare Tel: 04-793971-2 04-794756 E-mail: [email protected] Census Results for Midlands Province at a Glance Population Size Total 1 614 941 Males 776 787 Females 838 154 Annual Average Increase (Growth Rate) 2.2 Average Household Size 4.5 1 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................3 List of Tables.....................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................9 Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................10 Midlands Fact Sheet (Final Results) .................................................................................................13 Chapter 1: ........................................................................................................................................14 Population Size and Structure .......................................................................................................14 Chapter 2: ........................................................................................................................................24 Population Distribution -

ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee

SIRDC VAC ZIMBABWE Vulnerability Assessment Committee Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Financed by: Implementation partners: The ZimVAC acknowledges the personnel, time and material The Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines was made possible by contributions of all implementing partners that made this work contributions from the following ZimVAC members who supported possible the process in data collection, analysis and report writing: Office of the President and Cabinet Food and Nutrition Council Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Urban Development Ministry of Agriculture, Mechanisation and Irrigation Development For enquiries, please contact the ZimVAC Chair: Ministry of Labour and Social Services Food and Nutrition Council Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency SIRDC Complex Ministry of Health and Child Welfare 1574 Alpes Road, Hatcliffe, Harare, Zimbabwe Ministry of Education, Sports, Arts and Culture Save the Children Tel: +263 (0)4 883405, +263 (0)4 860320-9, Concern Worldwide Email: [email protected] Oxfam Web: www.fnc.org.zw Action Contre la Faim Food and Agriculture Organisation World Food Programme United States Agency for International Development FEWS NET The Baseline work was coordinated by the Food and Nutrition Council (FNC) with Save the Children providing technical leadership on behalf of ZimVAC. Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee August 2011 Page | 1 Zimbabwe Rural Livelihood Baselines Synthesis Report 2011 Acknowledgements Funding for the Zimbabwe Livelihoods Baseline Project was provided by the Department for International Development (DFID) and the European Commission (EC). The work was implemented under the auspices of the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee chaired by George Kembo. Daison Ngirazi and Jerome Bernard from Save the Children Zimbabwe provided management and technical leadership. -

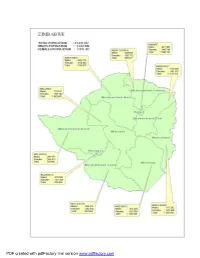

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 25 March 2011 ZIMBABWE 25 MARCH 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN ZIMBABWE FROM 22 FEBRUARY 2011 TO 24 MARCH 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON ZIMBABWE PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 22 FEBRUARY 2011 AND 24 MARCH 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Public holidays ..................................................................................................... 1.06 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 Remittances .......................................................................................................... 2.06 Sanctions .............................................................................................................. 2.08 3. HISTORY (19TH CENTURY TO 2008)............................................................................. 3.01 Matabeleland massacres 1983 - 87 ..................................................................... 3.03 Political events: late 1980s - 2007...................................................................... 3.06 Events in 2008 - 2010 ........................................................................................... 3.23 -

Final Book2.Indd

Sub-National Food Security Information System Livelihoods Profiles Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Table of Contents Table of Contents Acknowledgements Acronyms and Abbreviations Introduction Objective of the Report Methodology Background to Vulnerability and Risk Analysis Livelihoods Based Vulnerability Assessment Approach Livelihoods Zoning Wealth Break Down Analysis of Livelihoods Strategies Baseline + Hazard + Response = Outcome Field work Brief Background on Zimbabwe The Seven Food Economy Zones, Baseline Profiles Introduction Livelihood Zones Sub National FSIS general seasonal Calendar Rural Sources of Food and Cash Income Main Findings and Implications Poor Resources Kariba Valley, Kariangwe Jambezi Communal FEZ: Siabuwa Nebiri Low Cotton Producing Communal FEZ Kanyati High Potential FEZ Agro-fisheries ( Gache-Gache )FEZs Greater Northern Gokwe High Cotton Producing Communal FEZ Lusulu Lupane Southern Gokwe Platuea Mixed Agriculture FEZ Lusulu Lupane Southern Gokwe Lowlands Mixed Agiculture FEZ Greater Mudzi Communal FEZ Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Zimbabwe Livelihood Profiles Acknowledgements Acronyms and Abbreviations AIDS Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome CFSAM Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission CSO Central Statistics Office DFID Department For International Development Save the Children (UK) Zimbabwe, Catholic Relief Services and Concern World Wide (CWW) would EMOP Emergency Operations like to express their gratitude to the districts of Binga, Kariba, Mudzi, UMP, Nyanga North, Gokwe FANR Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources Directorate (SADC) North and South for their support towards the assessments used for the livelihoods profiles. Spe- FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation cific thanks is offered to the departments for Agriculture Research and Extension (AGRITEX) and District Aids Action Committees (DAAC) who provided some of the secondary data required for FEZ Food Economy Zone the Vulnerability Assessment and Analysis (VAA). -

Table of Contents Table of Contents

PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com Table of Contents Table of Contents...............................................................................................................................1 Foreword...........................................................................................................................................2 Executive Summary...........................................................................................................................3 Chapter 1:..........................................................................................................................................5 Population Size and Structure.........................................................................................................5 Chapter 2:........................................................................................................................................15 Population Distribution.................................................................................................................15 Chapter 3:........................................................................................................................................22 Internal Migration.........................................................................................................................22 Chapter 4:........................................................................................................................................47 Household Characteristics.............................................................................................................47 -

Impact Assessment of the Gokwe Integrated Recovery Action Project Zimbabwe

Impact Assessment of the Gokwe Integrated Recovery Action Project Zimbabwe John C Burns • Omeno W Suji August 2007 Impact Assessment of Innovative Humanitarian projects in Sub-Saharan Africa The Feinstein International Center in partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Africare Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Sekai Chikowero, Paul Chimedza, Stanley Masimbe, and James Machichiko, of Africare Zimbabwe for all their assistance and support during the mid term visits and final impact assessment. In particular we would like to thank Timm Musori for his participation and valuable contributions during the exercise. Our gratitude also goes to the rest of the Africare, Zimbabwe team for their hospitality and administrative support in Gokwe and Harare. To Dr Justice Nyamangara of the University of Zimbabwe for availing himself during the various technical presentations held in Harare, and for working on the baseline and indicator validation exercises. Many thanks also to the enumerators, Frank Magombezi, Paradza, Kunguvas, and Enock Muzenda for their valuable contribution during the final impact assessment. From the Feinstein International Center, thanks to Dr Peter Walker, Dr Andrew Catley, and Dr Dawit Abebe, for providing technical support. We would also like to thank Regine Webster, Mito Alfieri, and Kathy Cahill from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for all your support. 2 Contents Summary .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION -

LFSP—APN in Zimbabwe Newsletter

LFSP—APN in Zimbabwe Newsletter Agriculture Productivity and Nutrition (APN) component of LFSP is managed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations January, 2015 - June, 2015 Welcome to LFSP – APN entire four-year programme In this issue that is being implemented through three main compo- LFSP launched, a four year nents namely: journey begins An Agricultural Productivity ENTERPRIZE project highlights and Nutrition (APN) compo- EXTRA project brief nent being managed by the FAO is funded to the tune of INSPIRE project highlights US$48 million with the ob- Rural Finance rolls out jective of raising smallhold- er farm productivity by in- M&E Strategy workshop en- troducing improved and climate smart Welcome to the first issue of the hances common understand- agricultural practices, access to fi- Livelihood Food and Security Pro- ing of LFSP nance and markets and promote pro- gramme – Agriculture Productivity duction and consumption of safer and and Nutrition (LFSP-APN) newsletter Extension and Advisory Services, more nutritious foods. which will be published by FAO Rural Finance, Strategic Partners and twice a year. The newsletter is one of A Market Development (MD) com- Government counterparts. In addition the various platforms through which ponent being managed by GRM with the product will be enriched through the programme will share information the objective of linking smallholder close collaboration with GRM and and developments. farmers to profitable commercial Coffey, the other LFSP management markets as well as to stimulate de- organisations and their partners. This first issue comes at a very oppor- mand and supply of affordable nutri- tune time, when the LFSP-APN has We trust this newsletter will contrib- tious foods. -

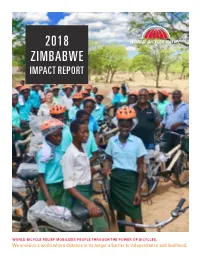

2018 Zimbabwe Impact Report

2018 ZIMBABWE IMPACT REPORT WORLD BICYCLE RELIEF MOBILIZES PEOPLE THROUGH THE POWER OF BICYCLES. We envision a world where distance in no longer a barrier to independence and livelihood. ZIMBABWE COUNTRY PROFILE 17.1M 43.3/Km2 POPULATION1 POPULATION DENSITY1 2 390,757 Km LIVE IN RURAL LIVE IN URBAN 2 2 SURFACE AREA1 68% AREAS 32% COMMUNITIES In areas of Zimbabwe where walking is the primary mode of In areas where distance is a transportation, distance is a challenge to earning a livelihood. challenge, meeting everyday needs is a struggle against time 38% and fatigue. OF RURAL ZIMBABWE LIVES ON LESS THAN 9Km $2 PER DAY3 AVERAGE DISTANCE TO A HEALTHCARE FACILITY7 SCHOOL ENROLLMENT RATE4 89% 49% 88% 48% PRIMARY GIRLS SECONDARY GIRLS PRIMARY BOYS SECONDARY BOYS LIFE EXPECTANCY1 HIV PREVALENCE1 ACCESS TO SAFE WATER1 59 YEARS 14.7% 96% REFERENCES: 1) http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/zimbabwe-population/ 3) https://www.hfgproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Zimbabwe_ 2) http://tradingeconomics.com/zimbabwe/rural-population-percent-of-total Health_System_Assessment20101.pdf -population-wbr-data.html 4) https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/zimbabwe_statistics.html http://uis.unesco.org/country/ZW 2018 ZIMBABWE IMPACT REPORT 3 DEAR FRIENDS We at World Bicycle Relief have the honour of being a world-class organization that is paving the way for increased mobility in Zimbabwe. Offering quality products and excellent service, we stand shoulder to shoulder with our global partners. Not everyone has the luxury of riding a bicycle when they really need it. However, when one does it often does the trick to bring one closer to one’s home environment and makes it easier to commit to various tasks, whilst making one healthier and happier. -

Child Poverty in Zimbabwe

Child Poverty in Zimbabwe An analysis using the Poverty Income Consumption and Expenditure Survey (PICES) 2017 Data 2019 1 The Zimbabwe Poverty Atlas was produced by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). Technical and financial support was provided by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Suggested citation: Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and UNICEF (2019). Zimbabwe Child Poverty Report 2019. Harare, Zimbabwe: ZIMSTAT and UNICEF. This material may be reprinted, quoted or otherwise reproduced, providing that the source is properly acknowledged. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency, 28th Floor Kaguvi Building, Corner S.V. Muzenda and Central, Harare, Tel.: (+263 242) 706681/8 and 703971/7, Internet: www.zimstat.co.zw United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Zimbabwe, 6 Fairbridge Avenue, Belgravia Harare, Tel.: (+263 242) 703941/2, 791812 and 703841, Internet: www.unicef.org/zimbabwe Design and layout: Catapult Media Photographs by: © UNICEF/2015/T. Mukwazhi © UNICEF/2015/G. Nardelli 2 Government of Zimbabwe Child Poverty in Zimbabwe 2019 An analysis using the Poverty Income Consumption and Expenditure Survey (PICES) 2017 Data for every child 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents ii List of tables iii List of figures iv List of abbreviations v Introduction 1 Conceptual framework and methodology 2 Definitions of poverty and concept of well-being 2 Data and methods 2 Findings 5 Geography of child poverty 5 Household structure and child poverty 9 Child poverty and education 17 Health status and access to health care -

Census Results in Brief

Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu