Statera Energy Saltholme Cowpen Bewley Stockton-On-Tees Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durhal\F. [ KELLY:'~

410 STOCKTON- U POX ... TEES. DURHAl\f. [ KELLY:'~ MAGISTRATEB FOR THE BOROUGH TEES V ALLEY WATER BO,Ul.D.. (which includes Norton). Offices, Mmlicipal buildings, Middlesbr()ugh & 14 .DQve The Mayor. cot street, Stockton. .Bagley Charles J ames, ·west wood, Hart burn Stockton Representatives on the Water BQard. ~ Bainbridge Rober·t, Outram street · Retire Retire llelltty William John L.R.C.P. & S.Edin. Van Mildert I Councillor R.F.Brittain I~Jl4 AldermanR.Bainbridge 1916 house, Yarm road Councillor T. Dowr.ey .• 1915 Alderman W. Ma\\lam J916 Brittain Robert Frank, Skinner street Alderman Tomkins 1915 Burns Hugh, 145 High street li. Cameron Alexander, 3 Hartington road Middlesbrough Representatives. ()raig David, Bridge road Retire t Retire Harrison John, 5 North terrace, Norton road Councillor J. T. Pannell 1914 Alderman A. Hinton..-.... 19~ Hodgson B. Tyson, g6 High street CouncillorS. A. Hauler 1914 Alderman R. Archibald ~916 Hunton John George, 15 West End terrace Councillor Calvert .•. 1915 Ald. J}lcLaughlan ·- 1916 Lee Robert, Fair:field J. J. Mellanby Thomas, Hawthorn house, Hartburn, Stockton Thornaby Representative. Mills Waiter Herbert, 16 Finkle street Vacant. Nattrass F. T. Arleswicke, Hartburn road Meetings of the Board at Municipal buildings, Middlett· Newby George, Io Finkle street brough, 2nd monday in every month at IO-So a.m Reed William, Hartburn lane, Stockton Meetings of the Stockton Water Supply committee are Robinson M. Hart burn held un 1st tuesday in every month at 2.45 p.m Roger Bobert, West row, Stockton Mee~ings of the Finance committee, on the wednesday pra· Samuel J onathan, Chester-le-Street Sanderson Henry G. -

Contents. Proceedings at the Nomination. Page Polling Districts

E S CONT NT . i Proceedings at the Nominat on . PAGE Polling Districts Castle Eden 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Gateshead Heworth Hetton - le -Hole J arrow Lanchester Seaham Harbour Shotley Bridge South Shields Sunderland Winlaton Analysis of the P011 A nalysis o f Districts A l o f n na yses Tow ships O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O Index of Townships RE F E RE N CE S l l f ll made to Doub e Entries in the Voting Co umns , where the o owing ‘ evi ations are used to denote other Districts CE for Castle Eden L for Lanchester CS Chester -le - Street SH Seaham Harbour D Durham SB Shotley Bridge G Gateshead SS South Shields H Heworth S Sunderland HH Hetton -le - Hole Wh Whickham J J arrow Wn Winlaton are l l Doub e Entries occur in the same District, the numbers on y are a—m PROCEEDING S AT THE NOMINATION . The Nomination for the Northern Division of the County o f Durham . l l ook p ace in the Market P ace , Durham , (the County Courts being i 2 oth o f 1 8 6 8 . nder repair) , on Friday, the November, . U ff Of . W E WOOLER, ESQ IRE , Under Sheri , Returning ficer _ SIR WI IA O of ll HEDWORTH LL MS N , BARONET , Whitburn Ha , was - of Elemore ll proposed by Henry John Baker Baker, Esquire , Ha , of f and seconded by Joseph Laycock, Esquire , Low Gos orth, l - - Newcast e upon Tyne . -

Application Site Condition Report

APPLICATION SITE CONDITION REPORT Saltholme North Gas Fired Generating Facility Permit Application EPR/LP3300PZ/A001 JER1691 Application Site Condition Report V1 Final 9 September 2019 rpsgroup.com Quality Management Version Revision Authored by Reviewed by Approved by Review date 0 Draft Frances Bodman Jennifer Stringer Jennifer Stringer 16/08/2019 Statera Energy / 0 Client comments Frances Bodman - 27/09/2019 Jennifer Stringer 1 Final Frances Bodman Jennifer Stringer Jennifer Stringer 09/09/2019 Approval for issue Jennifer Stringer Technical Director [date] File Location O:\JER1691 - Statera EP GHG and EMS\5. Reports\1. Draft Report\Saltholme_North\Appendix G - ASCR\190909 R JER1691 FB Applicaiton Site Condition Report v1 final .docx © Copyright RPS Group Plc. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Plc, any of its subsidiaries, or a related entity (collectively 'RPS'), no other party may use, make use of, or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. The report does not account for any changes relating to the subject matter of the report, or any legislative or regulatory changes that have occurred since the report was produced and that may affect the report. RPS does not accept any responsibility or liability for loss whatsoever to any third party caused by, related to or arising out of any use or reliance on the report. -

Hartlepool Greatham Billingham Stockton Middlesbrough Park End 36

Hartlepool z Greatham z Billingham z Stockton z Middlesbrough z Park End 36 via Marina, Oxford Road, Catcote Road, Owington Farm, Norton,Thornaby Station & North Ormesby Service 36 from Hartlepool Marina via Marina Way, Gateway Bridge,Victoria Road,York Road, Stockton Road, Oxford Road, Catcote Road, Owton Manor Lane, Stockton Road A689, Greatham High Street, Greatham Bridge, Stockton Road A689, Newton Bewley, Stockton Road, Seal Sands Link Road, Marsh House Avenue, Rievaulx Avenue, Melrose Avenue,The Causeway, Roseberry Road,Wolviston Road, Station Road, Billingham Green,West Road, South View, Billingham Bank, Billingham Road, Norton Road, Stockton High Street, Bridge Road,Victoria Bridge, Mandale Road, Middlesbrough Road, Stockton Road, Newport Road, Hartington Road, Brentnall Street, Grange Road, Middlesbrough Bus Station,Wilson Street,Albert Road, Corporation Road, Marton Road, Borough Road,West Terrace, Cromwell Street, King's Road, Ormesby Road, Ingram Road, Crossfell Road, Overdale Road.. MONDAY TO SATURDAY NS NS NS S NS + NS NS S NS S + E Service number 36A 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 36 Hartlepool Marina, Asda ------------0801 0816 DDA Aware Hartlepool, Victoria Road - - 0623 0628 - 0646 0703 0708 0720 - 0738 0753 0803 0819 Hartlepool, York Road Library - - 0625 0630 - 0648 0705 0710 0722 - 0740 0755 0806 0822 Please contact us if you Oxford Road, Catcote Road - - 0631 0636 - 0654 0711 0716 0728 - 0746 0801 0812 0828 have difficulty reading Rossmere Hotel - - 0635 0640 - 0658 0715 0720 0732 - 0750 0805 0816 0832 this -

Water Hardness

Water hardness Northumbrian Water is responsible for supplying a reliable source of safe, clean, drinking water. The majority of the company supply area is soft to slightly hard. Why some water is hard If your water comes from underground limestone or chalk rocks, or contains a proportion of groundwater, then the chances are that it is hard. The hardness is caused by the presence of minerals dissolved from the ground and rocks by the water. Northumbrian Water is compliant with the appropriate regulations and has no plans to introduce softening to hard water areas. Please find below a PDF document of the water hardness for the Northumbrian Water area, along with the measurement of hardness in degrees Clarke, for use with dishwashers and washing machines. You can check out how hard the water is in your area here by viewing the harness zones. What does this mean for my appliances? If your water is hard you will notice that your kettle and other water heating appliances become furred up with a white scale. You may also find this scale in your bath, sink and shower. It isn't harmful but can be a bit of a nuisance. Hard water can also affect appliances like washing machines, dishwashers and steam irons. If you are installing a new dishwasher, your plumber may ask you for the hardness of your water. If the manufacturer’s instructions show hardness using a different factor, you can convert the values as follows: x 2.5 = calcium carbonate (CaCO3) mg/l x 0.174 = Degrees Clarke Total hardness (as mg/l Ca) x 0.25 = French Degrees x 0.142 = German Degrees We do not change the natural hardness of the region’s water through treatment, it is left to the customer, either domestic or commercial, to decide whether artificial softening is the right choice for them. -

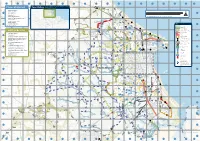

Walking and Cycling in Hartlep

O S N A QUEEN'SQU R R D O O A A D D RO B AD 1 D 2 ROAOA UEEN'S'S 8 FILLPOKE LANE Q 0 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R WingateW e MOOR LANE To Sunderland Monk and Peterlee For more information on cycling and walking in the area go to COAST ROADROA F R HesledenHe O N www.letsgoteesvalley.co.uk Places of interestT Tees Valley S To Crimdon & T R E Blackhall Rocks ET Crimdono Beck North Sands Crimd NesbittNes md Ward Jackson Park K5 A B1B Dene Ha on Beck Scale 1:20,000 128 r 0 t to K S TA H k HASW ELL AVENUE a Burn Valley Gardens L6 T s B IO Hartlepool w N el 0 Miles 12 R l W 1 O a 1 ADA D lk Rossmere Park L8 2 HARTLEPOOL wa A C y 1 0 B1280 SeatonSeSeaeatoneaatontononn CarewCCaCareCara eew 8 DURHAMRHAM 6 0 Kilometres 123 Seaton Park O8 D Thee C O MIM CommonCommommon A I S L F W E B T IN B EL R L GA OWSW R © Crown Copyright and database right 2018. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100015871. TETE R A N S BU D O Summerhill Country Park K6 StationStation D R O AD N N L A E A Redcar Central AN A L L E K BILLINGHAM D E E Bellows Burn T Redcar East C Townown C E Golf Course L R L CemeteryCemetery Billingham D E R OA A ET Hutton E R O Art Gallery / Tourist Information Centre M5 RE ILL C F C T V E S T E T Longbeck AR V A N H E N HenryHenry R O R BEB N R F Marske ELLLLOWSW O S BURURN E Saltburn LANE R A D W South Bank R IN A D G A St. -

Out-And-About-Walking-And-Cycling.Pdf

OutOutandandAboutAbout Walking and cycling in Stockton-on-Tees 1212 greatgreat placesplaces toto exploreexplore Big plans for great experiences OutandAbout In Stockton-on-Tees we are very 1 Wynyard Woodland Park lucky to have so many fantastic parks and other places to visit 2 Newham Grange Park/ right here on our doorstep, and Hardwick Dene lots of attractive traffic-free paths for getting around. 3 Grangefield Park This guide shows you twelve great destinations which you can reach easily by 4 Ropner Park/Six Fields walking or cycling. Whether you’re looking for a park with a playground, a place to 5 Coatham Wood walk your dog, or somewhere peaceful to enjoy wildlife you’ll find somewhere that’s 6 Preston Park/Quarry Wood just right for you. Use the handy key below to see at a glance 7 Romano Park what each destination has to offer. There’s 8 Tees Heritage Park Nature Reserves also a map at the end of this guide showing the featured parks and selected routes for walking and cycling. This includes the 9 Tees Barrage/Portrack Marsh National Cycle Network, other linking cycle paths, the Teesdale Way and the Thornaby 10 Billingham Beck Valley Country Park Trail. 11 John Whitehead Park For more detailed information about these (and other) parks and trails please use the 12 Cowpen Bewley Woodland Park web links provided. Welcome to Stockton’s great outdoors! IDEAL FOR IDEAL FOR CAFÉ TOILETS PLAY CAR BOWLING GAMES OUTDOOR TENNIS SKATE CYCLING WALKING AREA PARKING CLUB AREA GYM COURTS PARK 1 PLAY AREA CAFÉ TOILETS IDEAL FOR WALKING IDEAL FOR Wynyard Woodland Park CYCLING You’ll need plenty of time to explore • Admire the carpets of bluebells and every corner of this wonderful ramsons (wild garlic) on a springtime country park: from Thorpe Wood, walk in Thorpe Wood CAR PARKING an ancient woodland of oak, ash • Stroll through Pickards Meadow - the and wych elm, right up to Tilery size of over ten football pitches, it’s one Woods, Brierley Woods and Pickards of the biggest wildflower meadows in Meadow in the north. -

Trades. F.Ar 663

- DL:RB.AM.] TRADES. F.AR 663 Atkinson Wm. Old CassQp, Coxhoe Beadle Thom941, Low Shipleyf Soutb Bertram George, Ears den grange, Ayre John Geo. Tanfield, Tantobie Bedburn, Witton-le-Wear .Houghton-le-Spring Ayre John Robert, Riding ·hills, .Ann- Beck Bros. Walworth, Heighingtdn Best Charles, Pelton house & Moss field Plain Bedford Wm. Neasham rd.Darlington Close house, Pelton Ayre John Robert, West Kyo, Ann- Bee .Stephen, Esh, Durham Best John, Iveston, Leadgate field Plain Bell Mrs. Ann & Son,Whitwell house, Bt>st T. Old Park, Spennymoor Bailey J. East Rainton, Fence Houses Durham Best Thomas, Hilton, Darlington Bainbridge Brothers, Cockfield Bell Bros.Ltd.Sth.Brancepeth Colliery Best William, Thorney close, Silks- Bainbridge Brothers, High st. Norton, Bell GeOTge & John, Langleydale,Bar· worth, Sunderland Stocldon nard Castle Beveridge Thomas, Chester-le-Street Bainbridge James Edgar & Herbert, Bell A. Low ho.Newbiggin, Darlington Biglin Edward, Whiley hill, Coatham- Long Newton, Stockton Bell Mrs. Ann, Shincliffe, Durham M undeville, Darlington Bainbridge Frank, West .Auckland Bell Mrs. A. Whitton, Ferryhill Bignall Edward, Aycliffe, Darlington Bainbridge G. Moss, Forest, Darlingtn Bell Augustus, The Grange, Bishop- Binks .Mrs. E. Gore hall, Thornley Bainbridge George, Ash dub, Etters- ton, Ferryhill Binks John, West Witton, Witton- gill, Darlington Bell B. Cape ho. Carlton, Ferryhill le-Wear Bainbridge Isaac Orosby, Hill side, Bell Charles, High Stotfold, Elwick, Binks Robert, Lane house, Hamster- Ingleton, Darlington Castle Eden ley, Witton-le-Wear Bainbridge John, East 1Jridge end, Bell Mrs. C. Ushaw Moor, Durham Bird Mrs. Elizabeth, The Grange, Frosterley, Durham Bell Mrs. E. Hill, Cowshill, Wearhead Newton Bewley, Stockton Bainbridge John, Edmundbyers,Shot- Bell Mrs.E.Hunt hall,Forest,Darlngtn Bird Thomas, Wolviston, Stockton ley Bridge Bell Frederick, Billingham High Birkett Thomas, .Alwent hall,Winston, Bainb1·idge Jn. -

North East Regional Assembly Wind Farm Development and Landscape Capacity Studies: East Durham Limestone and Tees Plain

North East Regional Assembly Wind Farm Development and Landscape Capacity Studies: East Durham Limestone and Tees Plain North East Regional Assembly Wind Farm Development and Landscape Capacity Studies: East Durham Limestone and Tees Plain August 2008 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no Ove Arup & Partners Ltd responsibility is undertaken to any third Central Square, Forth Street, party Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 3PL Tel +44 (0)191 261 6080 Fax +44 (0)191 261 7879 www.arup.com Job number 123906 Document Verification Page 1 of 1 Job title Wind Farm Development and Landscape Capacity Studies: East Job number Durham Limestone and Tees Plain 123906 Document title Issue File reference Document ref Revision Date Filename Draft 1 25/02/08 Description First draft Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Cathy Edy Simon White/Simon Simon Power Power Signature Draft 2 04/07/08 Filename 004 Draft 02 Report_CE.doc Description Incorporating client revisions Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Cathy Edy Simon White/Simon Simon Power Power Signature Issue 05/08/08 Filename 005 Final Report_East Durham Limestone and Tees Plain.doc Description Issue Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Cathy Edy Simon White/Simon Simon Power Power Signature Filename Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Signature Issue Document Verification with Document 9 G:\ENVIRONMENTAL\EXTERNAL JOBS\DURHAM WIND\005 ISSUE FINAL Ove Arup -

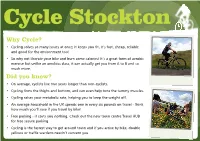

Short-Cycle-Route-Self-Guided.Pdf

Cycle Stockton Why Cycle? • Cycling solves so many issues at once; it keeps you fit, it’s fast, cheap, reliable and good for the environment too! • So why not liberate your bike and burn some calories! It’s a great form of aerobic exercise but unlike an aerobics class, it can actually get you from A to B and so much more. Did you know? • On average, cyclists live two years longer than non-cyclists. • Cycling firms the thighs and bottom, and can even help tone the tummy muscles. • Cycling raises your metabolic rate, helping you to keep the weight off. • An average household in the UK spends one in every six pounds on travel - think how much you’ll save if you travel by bike! • Free parking - it costs you nothing. Check out the new town centre Travel HUB for free secure parking. • Cycling is the fastest way to get around town and if you arrive by bike, double yellows or traffic wardens needn’t concern you. FREE Secure Cycle Parking from 7.30am - 6pm Mon - Fri FREE Information FREE Cycling Skills Advice and information on active travel. Been out of the saddle for a while? We can help FREE Guided Walks & Cycle Rides you regain your confidence on two wheels! Bike loans available. For cycle training contact Stockton Borough FREE Training Council cycle training on 01642 526735 or email [email protected]. Attend a maintenance training session and you can learn simple ways to keep your bike in tip- top shape. Stockton-on-Tees FREE workplace active travel solutions If your business wants to set up an active travel scheme or you are just thinking about cycling or walking to work yourself, we can help. -

Feasibility Study for a Brecks Visitor Centre

Stockton-on-Tees Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2008 - 2018 Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2008 - 2018 Published November 2007 Please Note – All representations received regarding the consultation of the draft plan have been taken into account and incorporated into the final ROWIP. A selection of images, etc. are still required to be included into the final plan, which will be arranged, after Cabinet approval. The plan is also available as a CD-ROM and can be downloaded from www.stockton.gov.uk For further information and copies please contact - Highway Network Management Section Technical Services Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council PO Box 229 Kingsway House Billingham TS23 2YL Or e-mail : [email protected] This document is also available in a number of different formats and languages to ensure it is fully accessible. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The Rights of Way Improvement Plan (ROWIP) is a requirement of section 60 of the Countryside and Rights of Way (CROW) Act 2000 and is intended to be the prime means by which the Council will identify changes to be made in respect of the management and improvement of the local rights of way network over the next 10 years. The ROWIP identifies the current issues affecting the use, management and maintenance of the local rights of way network, together with the actions that the Council proposes to undertake, both on its own and in partnership with others, in order to improve the existing network and to ensure that its potential is fulfilled over the next 10 years. In summary the ROWIP must contain the following: ¾ An assessment of the extent to which local rights of way meet the present and likely future needs of the public ¾ An assessment of the opportunities provided by local rights of way for exercise and other forms of open-air recreation and enjoyment of the authority’s area. -

Stockton (STK).Indd 1 11/10/2018 10:50

Stockton Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Stockton is a Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA PLUSBUS area. Rail replacement buses depart from the main road at the bottom of the PLUSBUS is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with station access road your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at August 2018) BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS BUS DESTINATION DESTINATION DESTINATION ROUTES STOP ROUTES STOP ROUTES STOP 13A 1 13A 1 Acklam { Summerville (Tesco extra) X8, X22 2 { 17A B Linthorpe (for Teesside University) 13 3 { X8 1 17A B Teesdale (Durham University, Queen's { Billingham ^ 35, 36, 52 3 X10 A 13A, X8, X22 1 { Campus - Thornaby ) ^ S1~, X12 D { Billingham (Owington Farm) 36, 52 3 13 3 36, 37, 38 4 { Teesside Industrial Estate 15 B { Billingham (Wolviston Court) 35 3 { Middlesbrough (Bus Station)* ^ X10 A X8 1 { Billingham (High Grange) 35 3 17A B S1~ D 36, 37, 38 C Teesside Shopping Park Billingham (Low Grange) 52 3 { 36, 37, 38 (short { X12, X66, X67 D walk from Middles- 4 { Bishopsgarth 59 2 { Mount Pleasant 35, 36, 37, 38, 52 3 brough Road) 15, X8, X22 1 Bishopton Road 59, X8 2 13, X8 2 { Newham Grange 36, 37, 38 4 { 3 Thornaby Rail Station ^ 61 E 13A { 17A B 13A, X8 1 { Bishopton Road West 59 2 Newport S1~, X12, X66, X67 D { 36, 37, 38 4 13 2 15 1 Thornaby (Town Centre) Newton Bewley 36 3 { 17A B { Carlton