The Downtown Hartford Transportation Project: Public-Private Collaboration on Transportation Improvements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut

MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS No. CT-359-A (Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF THE MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS NO. CT-359-A Location: Rear of 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut. USGS Hartford North Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates; 18.691050.4626060. Present Owner. Occupant. Use: Mark Twain Memorial, the former residence of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), now a house museum. The carriage house is a mixed-use structure and contains museum offices, conference space, a staff kitchen, a staff library, and storage space. Significance: Completed in 1874, the Mark Twain Carriage House is a multi-purpose barn with a coachman's apartment designed by architects Edward Tuckerman Potter and Alfred H, Thorp as a companion structure to the residence for noted American author and humorist Samuel Clemens and his family. Its massive size and its generous accommodations for the coachman mark this structure as an unusual carriage house among those intended for a single family's use. The building has the wide overhanging eaves and half-timbering typical of the Chalet style popular in the late 19th century for cottages, carriage houses, and gatehouses. The carriage house apartment was -

Downtown Development Plan

Chapter 7 One City, One Plan Downtown Development Plan KEY TOPICS Downtown Vision Hartford 2010 Downtown Goals Front Street Downtown North Market Segments Proposed Developments Commercial Market Entertainment Culture Regional Connectivity Goals & Objectives Adopted June 3, 2010 One City, One Plan– POCD 2020 7- 2 recent additions into the downtown include the Introduction Downtown Plan relocation of Capitol Community College to the Recently many American cities have seen a former G. Fox building, development in the movement of people, particularly young profes- Adriaen’s Landing project area, including the sionals and empty nesters, back into down- Connecticut Convention Center and the towns. Vibrant urban settings with a mix of uses Connecticut Center for Science and Exploration, that afford residents opportunities for employ- Morgan St. Garage, Hartford Marriott Down- ment, residential living, entertainment, culture town Hotel, and the construction of the Public and regional connectivity in a compact pedes- Safety Complex. trian-friendly setting are attractive to residents. Hartford’s Downtown is complex in terms of Downtowns like Hartford offer access to enter- land use, having a mix of uses both horizontally tainment, bars, restaurants, and cultural venues and vertically. The overall land use distribution unlike their suburban counterparts. includes a mix of institutional (24%), commercial The purpose of this chapter is to address the (18%), open space (7%), residential (3%), vacant Downtown’s current conditions and begin to land (7%), and transportation (41%). This mix of frame a comprehensive vision of the Downtown’s different uses has given Downtown Hartford the future. It will also serve to update the existing vibrant character befitting the center of a major Downtown Plan which was adopted in 1998. -

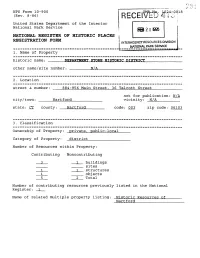

1 . Name of Property Other Name/Site

NPS Form 10-900 34-OQ18 (Rev. 8-86) RECE United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 2\ 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM JNTERAGENCY RESOURCES OMSION 1 . Name of Property historic name: ______ DEPARTMENT STORE HISTORIC DISTRICT ______________ other name/site number: _______N/A ______________________________ 2 . Location street & number: 884-956 Main Street. 36 Talcott Street __________ not for publication: N/A city/town: _____ Hartford __________ vicinity: N/A ________ state: CT county: Hartford______ code: 003 zip code: 06103 3 . Classification Ownership of Property: private, public-local ____ Category of Property: district_______________ Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 3 1 buildings ____ ____ sites 1 1 structures __ objects 2_ Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Resources of Hartford USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 2 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meej: the National Register Criteria. ___ See cont. sheet. 2/15/95_______________ Date John W. Shannahan, Director Connecticut Historical Crmni ggj ran State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. -

Passages Newsletter – Fall 2005

FALL 2005 PASSAGES ANCIENT BURYING GROUND ASSOCIATION, INC. “Passing Connecticut’s Heritage from Generation to Generation” Marty Flanders and Kathy Marr Honored with Hooker Award The 2005 Thomas Hooker Award honorees Marty Flanders (3rd from left) and Kathy Marr (2nd from right) pose with program par- ticipants (l to r) Susan Rottner, President of Bank of America Connecticut, John Boyer, Executive Director of the Mark Twain House and Museum, Bob Hill, President of ABGA, and Shep Holcombe, ABGA Chairman. (Avignone photo) n October 5, 2005, the Ancient Burying Twain House & Museum, and fundraiser for the Ground Association presented its annual award Connecticut Historical Society Museum and the Ohonoring the memory of Hartford’s founder, Antiquarian & Landmarks Society; and we welcome her the Reverend Thomas Hooker. The singular legacy of this year as a new member of the ABGA Board. “There are Thomas Hooker lies in the then-revolutionary concept many wonderful organizations in need of volunteers in he preached that a government derives its powers from Hartford,” she later said. “And we’ve had a lot of fun, too.” the consent of the people, and the award bearing his “I believe that when you have a lot, more is expected name is presented each year to one or two individuals of you,” stated Kathy Marr. A successful interior decora- whose leadership has improved the quality of life in the tor, Kathy has served on the Boards of the Connecticut Hartford community. River Museum in Essex, the Ivoryton Playhouse, the This year, the Thomas Hooker award was presented to Hartford Art School, the Mark Twain House & two women with distinguished records of community ser- Museum, where she served as Vice President and as head vice: Marty Flanders and Kathy Marr. -

Nscda-Ct Newsletter

NSCDA-CT NEWSLETTER VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 SEPTEMBER 2011 Message from the President Message from the Director Nancy MacColl Charles T. Lyle Dear Connecticut Dames, The summer has been busy with the exterior th I am privileged and honored to be the 39 President restoration of the Deane House in progress, which of the NSCDA in Connecticut. Torrey Cooke did an we expect to be finished in September. There are outstanding job as President for the last three years. also two or three weddings scheduled almost every She will continue as third Vice-President. weekend, bringing in over 100 people for each event. Katie Sullivan has booked sixty-nine A brief biography weddings and other rentals for this year and over for those of you who thirty are already booked for next year. do not know me. I was born in Boston, Work on the exterior of the Deane house started on MA, educated in June 17. The painters spent the bulk of the summer Washington, D.C. stripping paint and preparing the surfaces. At the (Holton-Arms School) same time, the carpenters have replaced rotted or and New York broken clapboards and made numerous woodwork (Bennett Junior repairs. All of the window sashes have been College). reglazed and broken window panes have been Torrey and Nancy in the Garden of Webb House replaced with old style wavy glass, a painstaking I married N. Alexander job that has taken most of the summer. Soon the MacColl (Alex), whose mother, Mary Kimbark masons will arrive to make repairs to the MacColl was a R.I. -

Sculpture in the City at the Wadsworth Activates Art and Architecture Online and on Main Street

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kim Hugo, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] Image files to accompany publicity of this announcement will be available for download at http://press.thewadsworth.org. Email to request login credentials. Sculpture in the City at the Wadsworth Activates Art and Architecture Online and on Main Street Hartford, Conn. (August 3, 2020)—Sculpture in the City is a cityscape-focused program launched in recent weeks activating the works of sculpture and architectural design on the grounds of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art and beyond. The Wadsworth’s historic buildings and installations of public sculpture, joined by two important works of public art neighboring the museum, Alexander Calder’s Stegosaurus and Carl Andre’s Stone Field Sculpture, are at the core of this effort. Signage on the grounds makes self-guided touring possible any day in person, aided by links to in-depth stories, archival images, and video content accessible anytime online. Live programming around the initiative spans guided outdoor art talks with Wadsworth curators, conservators, and education staff (available with advance registration) to content created by partnering organizations Connecticut’s Old State House, Hartford Public Library, and Judy Dworin Performance Project available online via thewadsworth.org/sculpture- in-the-city. “Every day, and especially now, we are focused on keeping art in people’s lives and enlivening the experience of everyone in our city,” said Thomas J. Loughman, director and CEO of the Wadsworth. “This opportunity to generate discussion and excitement around art, architecture, and history helps people appreciate our cityscape in this time before our reopening of the galleries later this summer.” The works of outdoor sculpture vary in style, material, and narrative; ranging from site markers of Revolutionary War history to contemporary abstractions referencing a horse, a flowering amaryllis, and World War II-era camouflage methods. -

Downtown Hartford Parking Lots & Garages

DOWNTOWN HARTFORD PARKING LOTS & GARAGES EXIT 50 Crowne I-91S 16 Plaza Hotel 30 Trumbull St. EXIT 32B Trumbull St. 40 42 28 43 41 47 21 6 29 I-91S << NO. CHAPEL ST. << MORGAN ST. NORTH EXIT 32A I-84W EXIT 48 Asylum Ave. 84 BULKELEY BRIDGE GREATER HARTFORD ARTS COUNCIL >> SO. CHAPEL ST. >> MORGAN ST SOUTH 45 Pratt Street, P.O. Box 231436 I-91N EXIT 49 18 11 5 Hartford, CT 06123-1436 8 Hilton EXIT 32A Ann/High St. Hartford Trumbull St. 34 >> TALCOTT ST. Phone: (860) 525-8629 Capital I-91N 23 36 32 2 7 Community 3 << HIGH ST. EXIT 32B Fax: (860) 278-5461 College I-84W SPRING ST. CHURCH ST. CHURCH ST. Email: [email protected] GARDEN ST. www.connectthedots.org 39 19 Constitution Hartford Plaza 22 26 Civic Center 46 ALLYN ST. >> PRATT ST. This map of parking 35 17 UNION STATION COLUMBUS BLVD. 91 MARKET ST. >> ANN ST. lots and garages was 37 SPRUCE ST. 24 14 1 25 3 >> UNION PL. TRUMBULL ST. created as a guide to << ASYLUM ST. Old State KINSLEY ST. House The help you find safe, 38 15 27 Goodwin MAIN ST. Hotel 10 3 EXIT 48A convenient and Constitution RIVER Asylum Ave. Plaza RIVERFRONT PLAZA affordable parking in CityPlace 3 33 EXIT 48B downtown Hartford. Capitol Ave. 13 ST. HAYNES 12 9 STATE ST. FOUNDERS BRIDGE PEARL ST. CENTRAL ROW I-84W The map shows the The Pavilion in TheaterWorks Bushnell Park 4 EXIT 54 Travelers GROVE ST. approximate locations Tower Capitol 31 Area of most surface lots and LEWIS ST. -

The Lyman Family of Hartford 1636 - 1925

The Lyman Family of Hartford 1636 - 1925 By Susan R. Barney January 2002 Saturday Morning Club Introduction and Summary On Feb. 6, 1925, a meeting took place in Mrs. Edward Dustin’s apartment at 351 Farmington Avenue in Hartford. Mrs. Dustin was aware that the house she lived in, once home to literary icon Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain) and his family, was on the market and under threat of demolition by a local developer. She and two other women, Mrs. Lewis Rose, (also a widow and resident of 351 Farmington Avenue), and Louise H. Fisher (Mrs. Herbert Field Fisher) called the meeting because of their desire to save the landmark designed by Edward Tuckerman Potter, and to establish the first private women’s club with a clubhouse in Connecticut.1 Also present were ten other women, among them Miss Annie Eliot Trumbull, Mrs. C. Morgan Aldrich, Mrs. John T. Robinson and Mrs. Philip Barton. Discussion centered on the feasibility of acquiring the $100,000, 54-year-old structure as a clubhouse. Following a unanimous vote, Louise Fisher’s husband, Herbert, a Realtor, drew up and secured an option to buy the house on behalf of the group. Later that month, Mr. Fisher identified two additional properties, 22 and 61 Woodland Street, with clubhouse potential as an alternative to 351 Farmington Avenue. Just around the corner from the Mark Twain House, 22 Woodland Street had become available following Mrs. Lyman’s death on February 17, 1925, eleven days after the committee first met. The former Lyman home, an 1895 Colonial Revival structure, was only 30 years old. -

CTFASTRAK SYSTEM MAP Y WOODSIDE VILLAGE

CTFASTRAK SYSTEM MAP y WOODSIDE VILLAGE Tunxis Mark 54 30 indsor Main W ROUTES: For more information, please visit www.cttransit.com. Hartford / New Britain via CTfastrak g 101 84 et tle I- FILLEY Cadwell FEDERATION ury THE HARTFORD onb 102 Hartford / New Britain / Bristol via CTfastrak Myr POND int tianuck wn HOME .W a UConn Health / Hartford / MCC via CTfastrak o PLAZA W E Express Bus service to/from downtown 121 r ALEXANDRIA ry intonbur M CTtransit/Hartford Hartford / Westfarms via CTfastrak / New Britain via Stanley St B onbu y Nutme 128 MANOR Wint Hartford from this Park & Ride Lot provided by Co Garde METRO CENTER 52 36 to gswell Spring LINCOLN FINANCIAL the 903-MANCHESTER-BUCKLAND EXPRESS. 923 Churc I-84 Manchester Mountain CLEAR EDGE Bradley Flyer Locust Street 923 Bristol Express via CTfastrak n h Connections to HILTON HOTEL 32 Newber 924 Cheshire / Southington Express via CTfastrak 924 ook Amtrak BLOOMFIELD indbr SOUTH WINDSOR Park Street–New Park Avenue Farmington Avenue Waterbury Express via CTfastrak HARTFORD STAGE 121 ome W WINDSOR ry 925 UNION STATION SAV-MOR Blue Seymour Asylum 925 r P chool Rood COMMUNITY HALL Chu Talcott ar S Ford SHOPPING 928 Waterbury / Cheshire / Southington Express via CTfastrak Allyn rch Je BLOOMFIELD k PLAZA Windsor Avenue Broad Street 928 U h PRUDENTIAL CAPITAL COMM. CENTER Uccello XL CENTER Hills Midian UnionU TOWN HALL ROCKWELL Hig H COLLEGE mbus Pa lu r rumbull t 74 k HHOMEWOOD SUITES Ann T Park Street–Park Road Farmington Avenue–North Main Street CONSTITUTION c LP WILSON Co Farmington Farmington HARTFORD 21 RESIDENCE INN PLAZA Rockwell CORNER 36 WOOD MEMORIAL Asylum Pratt yler COMMUNITY Broad 101 LIBRARY Windsor Avenue–International Drive Hillside Avenue 102 T CENTER rospe e e 34 Fo UCONN Cottage Grov 50 rov Market STATE P 128 153 E. -

A Case Study of Three Alternative Schools : an Analysis from a Black Perspective

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1972 A case study of three alternative schools : an analysis from a black perspective. Floyd H. Martin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Martin, Floyd H., "A case study of three alternative schools : an analysis from a black perspective." (1972). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2610. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2610 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CASE STUDY OF THREE ALTERNATIVE SCHOOLS: AN ANALYSIS FROM A BLACK PERSPECTIVE (October 1972) FLOYD H. MARTIN, JR. B. S. - Central Connecticut State College, New Britain M.S. - University of Hartford, Hartford, Connecticut ABSTRACT The primary thrust of this study involved a descriptive analysis of three alternative schools: The Everywhere School, the Alternative Center for Education, and Shanti, a Regional High School, all located in Hartford, Connecti- cut. The study was designed to determine to what degree these schools met the needs of their Black students and how these needs were affected by the existence of white racism. A case study approach from the perspective of a Black researcher was used. The basic research techniques were interviews, personal observations and experiences of the researcher, backed up by a review of literature on curriculum racism in education, teacher characteristics, and expectations, and Black community involvement. -

Obituary Manchester Mayor John ’Thompson Has BOLTON — Choice Listing One Rham Teacher in Mid 30S

PAGE EIGHTEEN - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD, Manchester. Conn., Fri., Jan. 28. 1973 Pray For Peace The Weather Out of Town-for Solo 7B Success Tonight * Conference Feb> 13 O’Neill Penalizes Cloudy with periods of rain tonight. Lows Obituary Manchester Mayor John ’Thompson has BOLTON — Choice listing one Rham Teacher in mid 30s. Considerable cloudiness Sun asked town residents to take time at 7 bednxnn deluxe home^ r i^ t on Refuse Collectors day with high im'mid 40s. Precipitation In all areas of the industrial In Police Dispute the lake. Maximum pnvacy. (Continued from Page One) Jacob A. Storrs p.m. today for a moment of prayer and iianrl|TBtTr € probability 70 per cent tonight, 20 per cent arts facility at Rham, equip thanksgiving for the cease-fire in Viet- Load«l with extras. Owners An infonhal conference on centers on the wording on an Jacob Allen Storrs, 68, of Director of Public Works checked regularly for Sunday. davsky’s department at Rham. ment was laid out with safety in Florida bound. T. J. Crockett the labor dispute between the emergency sick leave provision Cheriton, Va., formerly of William O’Neill, after meetings violations. R ^ ltor, 643-1577. As stated in the April article, mind. In'Addition, students are MANCHESTER — A City o f Village Charm Town of Manchester and the in the 1972-1974 police contract Manchester, d i^ ’Thursday at a with representatives of three Private refuse contractors “ Safety is an attitude which instructed in general safety MANCHESTER, Conn., SATURDAY, JANUARY 27, 1973 - VOL. XCII. No. 99 SIXTEEN PAGES — 2 TV — 2 MINI PAGES PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS Manchester Police Union l/)cal — The union claims that Weiss Cheriton nursing home. -

Splendor-IX-Benefit-Auction.Pdf

IX Ninth Annual Benefit Gala WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART NEW SINCE 1842 October 1, 2016 LIVE AUCTION LA-1 Artist: Henry Rodman Kenyon Title: On the Mill Pond, 1910 Media: Oil on board Unframed Size: 10 ½” x 13 ¾” Framed Size: 16” x 20” Henry Rodman Kenyon generally painted small, subtle sketches, which, despite their size, are strong and hold their own alongside larger contemporary works. His paintings suggest a man greatly in tune with nature; his brushstrokes are painterly and free, express - ing life and vitality and reflect well his vision of the world. His style has been best described as a mixture of the Barbizon and Impressionist schools, clearly indicated in his work On the Mill Pond . Stunning exploration of pastel pink hues and consideration of nature’s beauty indicates the artist’s inexplicable ability to capture the viewer. DONOR: The Cooley Gallery VALUE: $2,000 MINIMUM BID: $670 LA-2 Bottle of La Mission Haut Brion Vintage 1982 Perfect condition - stored in temperature controlled cellar since release. 100 pts. - Parker 19/20 J. Robinson - drink now (decant first) or cellar for up to fifteen years. DONOR: David Roth VALUE: $1,500 MINIMUM BID: $750 LA-3 Artist: Rob de Oude Title: Dicey Dissolve, 2014 Media: Oil on canvas Size: 32” x 32” Rob de Oude studied painting, sculpture and art history at the Hoge School voor de Kun - sten in Amsterdam and SUNY Purchase, NY. He has shown in the US and abroad, notably at Galerie Gourvennec Ogor in Marseille, France, Storefront Bushwick in Brooklyn, NY, McKenzie Fine Art in New York, NY, BRIC Rotunda in Brooklyn, NY, Galerie van den Berge in Goes, NL, City Ice Arts in Kansas City, MO, and has participated in several art fairs in New York, Miami and Paris.