Coltsville Special Resource Study November 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut

MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS No. CT-359-A (Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF THE MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS NO. CT-359-A Location: Rear of 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut. USGS Hartford North Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates; 18.691050.4626060. Present Owner. Occupant. Use: Mark Twain Memorial, the former residence of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), now a house museum. The carriage house is a mixed-use structure and contains museum offices, conference space, a staff kitchen, a staff library, and storage space. Significance: Completed in 1874, the Mark Twain Carriage House is a multi-purpose barn with a coachman's apartment designed by architects Edward Tuckerman Potter and Alfred H, Thorp as a companion structure to the residence for noted American author and humorist Samuel Clemens and his family. Its massive size and its generous accommodations for the coachman mark this structure as an unusual carriage house among those intended for a single family's use. The building has the wide overhanging eaves and half-timbering typical of the Chalet style popular in the late 19th century for cottages, carriage houses, and gatehouses. The carriage house apartment was -

Downtown Development Plan

Chapter 7 One City, One Plan Downtown Development Plan KEY TOPICS Downtown Vision Hartford 2010 Downtown Goals Front Street Downtown North Market Segments Proposed Developments Commercial Market Entertainment Culture Regional Connectivity Goals & Objectives Adopted June 3, 2010 One City, One Plan– POCD 2020 7- 2 recent additions into the downtown include the Introduction Downtown Plan relocation of Capitol Community College to the Recently many American cities have seen a former G. Fox building, development in the movement of people, particularly young profes- Adriaen’s Landing project area, including the sionals and empty nesters, back into down- Connecticut Convention Center and the towns. Vibrant urban settings with a mix of uses Connecticut Center for Science and Exploration, that afford residents opportunities for employ- Morgan St. Garage, Hartford Marriott Down- ment, residential living, entertainment, culture town Hotel, and the construction of the Public and regional connectivity in a compact pedes- Safety Complex. trian-friendly setting are attractive to residents. Hartford’s Downtown is complex in terms of Downtowns like Hartford offer access to enter- land use, having a mix of uses both horizontally tainment, bars, restaurants, and cultural venues and vertically. The overall land use distribution unlike their suburban counterparts. includes a mix of institutional (24%), commercial The purpose of this chapter is to address the (18%), open space (7%), residential (3%), vacant Downtown’s current conditions and begin to land (7%), and transportation (41%). This mix of frame a comprehensive vision of the Downtown’s different uses has given Downtown Hartford the future. It will also serve to update the existing vibrant character befitting the center of a major Downtown Plan which was adopted in 1998. -

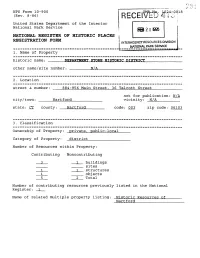

1 . Name of Property Other Name/Site

NPS Form 10-900 34-OQ18 (Rev. 8-86) RECE United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 2\ 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM JNTERAGENCY RESOURCES OMSION 1 . Name of Property historic name: ______ DEPARTMENT STORE HISTORIC DISTRICT ______________ other name/site number: _______N/A ______________________________ 2 . Location street & number: 884-956 Main Street. 36 Talcott Street __________ not for publication: N/A city/town: _____ Hartford __________ vicinity: N/A ________ state: CT county: Hartford______ code: 003 zip code: 06103 3 . Classification Ownership of Property: private, public-local ____ Category of Property: district_______________ Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing 3 1 buildings ____ ____ sites 1 1 structures __ objects 2_ Total Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: 1 Name of related multiple property listing: Historic Resources of Hartford USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form Page 2 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets does not meej: the National Register Criteria. ___ See cont. sheet. 2/15/95_______________ Date John W. Shannahan, Director Connecticut Historical Crmni ggj ran State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets does not meet the National Register criteria. __ See continuation sheet. -

The Springfield Armory Historic Background

The Springfield Armory Historic Background Report by Todd Jones, Historic Preservation Specialist Federal Emergency Management Agency October 2011 The Springfield Armory Exceptionally unique among the structures in Springfield, MA, the Springfield Armory has stood on Howard Street for over one hundred years. Yet, with its impressive medieval architecture, the building could easily pass for a centuries-old European castle. It may appear as a much unexpected feature on the skyline of a Connecticut River Valley city, but considering Springfield’s illustrious history as a manufacturer of war goods, a castle is actually quite an appropriate inclusion. The Armory is located today at 29 Howard Street. It is surrounded by a dense urban community characterized by commercial interests, with parking lots, a strip mall, and an apartment block included as its primary neighbors. The area transitioned from an urban working class residential neighborhood to its present commercial character during the mid and late twentieth century. Figure 1: Location of the State Armory in Springfield, 29 Howard Street, Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts (42.10144, -72.60216).1 Figure 2: Topographic map of Springfield showing the location of the State Armory.2 1 http://mapper.acme.com, accessed September 22, 2011 2 http://mapper.acme.com, accessed September 22, 2011. ______________________________________________________________________________ Attachment A. Historic Background Page 2 The 1895 Armory The structure was finished in 1895 for the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia (MVM), referred to in modern times as the Massachusetts National Guard. It was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Wait & Cutter, led by Robert Wait and Amos Cutter, who also planned the Fall River Armory at the same time. -

The Spirit of the Heights Thomas H. O'connor

THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian to An e-book published by Linden Lane Press at Boston College. THE SPIRIT OF THE HEIGHTS THOMAS H. O’CONNOR university historian Linden Lane Press at Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts Linden Lane Press at Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue 3 Lake Street Building Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02467 617–552–4820 www.bc.edu/lindenlanepress Copyright © 2011 by The Trustees of Boston College All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval) without the permission of the publisher. Printed in the USA ii contents preface d Thomas H. O’Connor v Dancing Under the Towers 22 Dante Revisited 23 a “Dean’s List” 23 AHANA 1 Devlin Hall 24 Alpha Sigma Nu 2 Donovan, Charles F., S.J. 25 Alumni 2 Dustbowl 25 AMDG 3 Archangel Michael 4 e Architects 4 Eagle 27 Equestrian Club 28 b Bands 5 f Bapst Library 6 Faith on Campus 29 Beanpot Tournament 7 Fine Arts 30 Bells of Gasson 7 Flutie, Doug 31 Black Talent Program 8 Flying Club 31 Boston “College” 9 Ford Tower 32 Boston College at War 9 Fulbright Awards 32 Boston College Club 10 Fulton Debating Society 33 Bourneuf House 11 Fundraising 33 Brighton Campus 11 Bronze Eagle 12 g Burns Library 13 Gasson Hall 35 Goldfish Craze 36 c Cadets 14 h Candlemas Lectures 15 Hancock House 37 Carney, Andrew 15 Heartbreak Hill 38 Cavanaugh, Frank 16 The Heights 38 Charter 17 Hockey 39 Chuckin’ Charlie 17 Houston Awards 40 Church in the 21st Century 18 Humanities Series 40 Class of 1913 18 Cocoanut Grove 19 i Commencement, First 20 Ignatius of Loyola 41 Conte Forum 20 Intown College 42 Cross & Crown 21 Irish Hall of Fame 43 iii contents Irish Room 43 r Irish Studies 44 Ratio Studiorum 62 RecPlex 63 k Red Cross Club 63 Kennedy, John Fitzgerald 45 Reservoir Land 63 Retired Faculty Association 64 l Labyrinth 46 s Law School 47 Saints in Marble 65 Lawrence Farm 47 Seal of Boston College 66 Linden Lane 48 Shaw, Joseph Coolidge, S.J. -

Download NARM Member List

Huntsville, The Huntsville Museum of Art, 256-535-4350 Los Angeles, Chinese American Museum, 213-485-8567 North American Reciprocal Mobile, Alabama Contemporary Art Center Los Angeles, Craft Contemporary, 323-937-4230 Museum (NARM) Mobile, Mobile Museum of Art, 251-208-5200 Los Angeles, GRAMMY Museum, 213-765-6800 Association® Members Montgomery, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 334-240-4333 Los Angeles, Holocaust Museum LA, 323-651-3704 Spring 2021 Northport, Kentuck Museum, 205-758-1257 Los Angeles, Japanese American National Museum*, 213-625-0414 Talladega, Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center, 256-761-1364 Los Angeles, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, 888-488-8083 Alaska Los Angeles, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 323-957-1777 This list is updated quarterly in mid-December, mid-March, mid-June and Haines, Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center, 907-766-2366 Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, 213-621-1794 mid-September even though updates to the roster of NARM member Kodiak, The Kodiak History Museum, 907-486-5920 Los Angeles, Skirball Cultural Center*, 310-440-4500 organizations occur more frequently. For the most current information Palmer, Palmer Museum of History and Art, 907-746-7668 Los Gatos, New Museum Los Gatos (NUMU), 408-354-2646 search the NARM map on our website at narmassociation.org Valdez, Valdez Museum & Historical Archive, 907-835-2764 McClellan, Aerospace Museum of California, 916-564-3437 Arizona Modesto, Great Valley Museum, 209-575-6196 Members from one of the North American -

Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Dean Krute, Carol, "Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 183. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/183 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Cheney Brothers, the New York Connection Carol Dean Krute Wadsworth Atheneum The Cheney Brothers turned a failed venture in seri-culture into a multi-million dollar silk empire only to see it and the American textile industry decline into near oblivion one hundred years later. Because of time and space limitations this paper is limited to Cheney Brothers' activities in New York City which are, but a fraction, of a much larger story. Brothers and beginnings Like many other enterprising Americans in the 1830s, brothers Charles (1803-1874), Ward (1813-1876), Rush (1815-1882), and Frank (1817-1904), Cheney became engaged in the time consuming, difficul t business of raising silk worms until they discovered that speculation on the morus morticaulis, the white mulberry tree upon which the worms fed, might be far more profitable. As with all high profit operations the tree business was a high-risk venture, throwing many investors including the Cheney brothers, into bankruptcy. -

Coltsville National Historical Park April 2015 Newsletter

National Park Service (NPS) Coltsville National Historical Park U.S. Department of the Interior April 2015 Newsletter Coltsville National Historical Park - For that must be accomplished before the Secretary almost 15 years, a diverse coalition has of Interior can formally establish the park. championed the establishment of the Coltsville Essentially, there are a series of agreements that National Historical Park. They can finally must be negotiated and signed. celebrate. In December, 2014 Congress passed and the President signed legislation authorizing The three agreements are with: the park. Once established, Coltsville National 1. Owners of the Colt Armory complex Historical Park will join the Weir Farm National to secure the donation of at least 10,000 Historic Site, 2 other National Heritage Areas, 8 square feet of space for a visitor center. National Natural Landmarks, and 61 National 2. City of Hartford to ensure that public Historic Landmarks in Connecticut as part of property, primarily Colt Park, is the National Park Service (NPS). The Coltsville managed for preservation and use as a Historic District is currently a National Historic national park. Landmark District in Hartford, Connecticut. The 3. Episcopal Church of Connecticut to district encompasses the factory, worker secure a preservation easement on both housing, community facilities and owner the Church of the Good Shepherd and residences associated with Samuel Colt, one of the Caldwell Colt Parish House. the nation's early innovators in precision manufacturing and the production of firearms. Development of Partnerships -Initial contacts Armsmear, the Colt’s mansion was originally with our partners in the development of the designated a national landmark in 1966. -

Metropolitan Boston Downtown Boston

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

When Visitors to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art Read A

1 “For Paintings of Fine Quality” The Origins of the Sumner Fund at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art On August 16, 1927, Frank B. Gay, Director of the Wadsworth Atheneum, wrote to Edward W. Forbes, Director of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard, that by the death last week of Mrs. Frank Sumner the Frank Sumner estate now comes to us. I learn from the Trust Company, his trustees and executor that the amount will be upwards of $2,000,000 ‘the income to be used in buying choice paintings.’ Of course we are quite excited here over the prospect for our future.1 The actual amount of the gift was closer to $1.1 million, making the Sumner bequest quite possibly the largest paintings purchase fund ever given to an American museum. Yet few know the curious details of its origins. Today, when visitors to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art read a label alongside a work of art, they will often see “The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund.” These visitors may well visualize two women—perhaps sisters, perhaps mother and daughter—strolling arm in arm through the galleries of the museum in times past, admiring the art and wondering what they might do for the benefit of such a worthy institution. They would be incorrect. The two women were, in fact, sisters-in-law who died fifty-two years apart and never knew each other. Since 1927 the Sumner Fund has provided the Atheneum with the means to acquire an extraordinary number of “choice paintings.” As of July 2012, approximately 1,300 works of art have been purchased using this fund that binds the names of Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner together forever. -

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Washington University in St. Louis Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts

Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum Washington University in St. Louis Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts Spotlight Essay: Thomas Cole, Aqueduct near Rome, 1832 February 2016 William L. Coleman Postdoctoral Fellow in American Art, Washington University in St. Louis When the Anglo-American landscape painter Thomas Cole made his first visit to Italy in the summer of 1831, he embarked on intensive study not only of paintings and sculptures, as so many visiting artists had before him, but also of ancient and modern Italian architecture. In so doing he launched a new phase of his career in which he entered into dialogue with a transatlantic lineage of “painter-architects” that includes Michelangelo, Raphael, and Rubens— artists whose ambitions were not confined to canvas and who were involved extensively with the design and construction of villas and churches, among other projects. Cole was similarly engaged with building projects in the latter decades of his short career, but a substantial body of surviving writings, drawings, and, indeed, buildings testifying to this fact has been largely overlooked by scholars, Thomas Cole, Aqueduct near Rome, 1832. Oil on canvas, 44 1/2 x 67 5/16". Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. presumably because it does not fit neatly with University purchase, Bixby Fund, by exchange, 1987. the myth of Cole as “the father of the Hudson River School” of American landscape painting.1 For an artist whose chief contribution, we have been told, is the argument his work offers for landscape painting as an art of the intellect rather than of mere mechanical transcription of outward appearances, his abiding commitment to the science of building and his professional aspirations in that direction are hard to explain. -

The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 40 Number 1 Editorial

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 40 Number 1 Editorial The Artist’s Shadow The Winter Show at the Park Avenue Armory in New York City is always a feast for the eyes. Dazzling works of art, decorative arts, and sculpture appear that we might never see again. During a tour of this pop-up museum in January I paused at the booth of the Alexander Gallery where a painting caught my eye. It was an 1812 portrait of two endearing native-New Yorkers Schuyler Ogden and his sister, the grand-nephew and grand-niece of General Stephen Van Rensselaer. I am always sure that exhibitors at such shows can distinguish the buyers from the voyeurs in a few seconds but that did not prevent the gallery owner from engaging with me in a lively conversation about Fresh Raspberries . It was clear he had considerable affection for the piece. Were I a buyer, I would have very happily bought this little confection then and there. The boy, with his plate of fresh picked berries, reminds me of myself at that very age. These are not something purchased at a market. These are berries he and his sister have freshly picked just as they were when my sisters and I used to bring bowls of raspberries back to our grandmother from her berry patch, which she would then make into jam. I have no doubt Master Ogden and his beribboned sister are on their way to present their harvest to welcoming hands. As I walked away, I turned one last time to bid them adieu and that is when I saw its painter, George Harvey.