The Cultural Politics of Textile Craft Revivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bargarh District

Orissa Review (Census Special) BARGARH DISTRICT Bargarh is a district on the Western border of The district of Bargarh is one of the newly Orissa. Prior to 1992, it was a subdivision of created districts carved out of the old Sambalpur Sambalpur district. Bargarh has been named after district. It has a population of 13.5 lakh of which the headquarters town Bargarh situated on the 50.62 percent are males and 49.38 percent left bank of the Jira river. The town is on the females. The area of the district is 5837 sq. Km National Highway No.6 and located at 59 km to and thus density is 231 per sq.km. The population the west of Sambalpur district. It is also served growth is 1.15 annually averaged over the decade by the D.B.K railway running from Jharsuguda of 1991-2001. Urban population of the district to Titlagarh. The railway station is about 3 kms constitute 7.69 percent of total population. The off the town. A meter gauge railway line connects Scheduled Caste population is 19.37 percent of Bargarh with the limestone quarry at Dunguri. The total population and major caste group are Ganda main Hirakud canal passes through the town and (54.82), Dewar (17.08) and Dhoba etc. (6.43 is known as the Bargarh canal. percent) among the Scheduled Castes. Similarly The District of Bargarh lies between the Scheduled Tribe population is 19.36 percent 200 45’ N to 210 45’N latitude and 820 40’E to of total and major Tribes groups of the total Tribes 830 50’E longitude. -

Bargarh District, Odisha

MIGRATION STUDY REPORT OF 1 GAISILAT BLOCK OF BARGARH DISTRICT OF ODISHA PREPARED BY DEBADATTA CLUB, BARGARH, ODISHA SUPPORTED BY SDTT, MUMBAI The Migration Study report of Gaisilat block of Bargarh district 2 Bargarh district is located in the western part of the state of Odisha come under Hirakud command area. The district continues to depict a picture of chronic under development. The tribal and scheduled caste population remains disadvantaged social group in the district, In this district Gaisilat Block Map absolute poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition are fundamental form of deprivation in which seasonal migration of laborers takes place. About 69.9 percent of the rural families in Bargarh are below the poverty line; of this 41.13 percent are marginal farmers, 22.68 percent small farmers and 25.44 percent agricultural laborers. Bargarh district of Odisha is prone to frequent droughts which accentuate the poverty of the masses and forces the poor for migration. In our survey area in 19 Grampanchyats of Gaisilat Block of Bargarh District where DEBADATTA CLUB (DC) has been undertaken the survey and observed that in many villages of these western Orissa districts almost half of the families migrate out bag and baggage during drought years. Only old and infirm people under compulsion live in the village. All able-bodied males and females including small children move out to eke out their living either as contract workers in the brick kiln units or as independent wage workers/self-employed workers of the urban informal sector economy in relatively developed regions of the state and outside the state. -

Socio-Economic Profile of Handloom Weaving Community: a Case Study of Bargarh District, Odisha

Socio-Economic Profile of Handloom Weaving Community: A Case Study of Bargarh District, Odisha A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela In partial fulfilment of the requirement of the award of the Degree of Master of Arts in Development Studies Submitted by SANDHYA RANI DAS Roll No. - 413HS1006 Under the Supervision of Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra Department of Humanities and Social Sciences NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, ROURKELA SUNDARGARH - 769008, ODISHA, INDIA MAY 2015 I DECLARATION I, hereby declare that my final year project on “Socio-Economic profile of Handloom weaving community: A case study of Bargarh District, Odisha" at National Institute of Technology Rourkela, Odisha in the academic year 2014-15 is submitted under the supervision of Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra. The information submitted here is true and original to the best of my knowledge. Sandhya Rani Das R. N. 413HS1006 MA in Development Studies Department of Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Technology, Rourkela II Dr. Bikash Ranjan Mishra Date: Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Rourkela National Institute of Technology Rourkela- 769008 Odisha, India CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the dissertation entitled, “Socio- Economic Profile of Handloom weaving community: A Case study of the Bargarh District, Odisha” submitted by Sandhya Rani Das in partial fulfilment of requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Development Studies of the department of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, Odisha, is carried out by her under my supervision. To the best of my knowledge the subject embodied in the dissertation has not been submitted to any other University for the award of any degree. -

Prevalence of and Factors Contributing to Anxiety, Depression and Cognitive

Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 80 (2019) 38–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/archger Prevalence of and factors contributing to anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders among urban elderly in Odisha – A study through the health T systems’ Lens ⁎ Sudharani Nayaka, Mrinal Kar Mohapatrab, Bhuputra Pandab, a Government of Odisha, Health and Family Welfare Department, Nilakantha Nagar, Nayapalli, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 751012, India b PHFI, Indian Institute of Public Health, Plot No. 267/3408, Jayadev Vihar, Mayfair Lagoon Road, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 751013, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Growing geriatric mental health needs of urban population in India pose several programmatic Anxiety challenges. This study aimed to assess anxiety, depression and cognitive disorders among urban elderly, and Depression explore availability of social support mechanisms and of a responsive health system to implement the national Cognitive disorders mental health programme. Elderly Methods: 244 respondents were randomly selected from Berhampur city. We administered a semi-structured Odisha interview schedule to assess substance abuse, chronic morbidity, anxiety, depression and cognitive abilities. Health systems Further, in-depth interviews were conducted with 25 key informants including district officials, psychiatrists, and programme managers. We used R software and ‘thematic framework’ approach, respectively, for quanti- tative and qualitative -

Brief Industrial Profile of Bargarh District

Brief Industrial Profile of Bargarh District ( 2 0 1 9 - 20) MSME - Development Institute , C u t t a c k (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India) As per the Guidelines issued by O/o DC (MSME), New Delhi Tele Fax: 0671- 2201006 E. Mail: [email protected] Website: www.msmedicuttack.gov.in F O R E W O R D Every year Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Development Institute, Cuttack under the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India undertakes the Industrial Potentiality Survey for districts in the state of Odisha and brings out the Survey Report as per the guidelines issued by the office of Development Commissioner (MSME), Ministry of MSME, Government of India, New Delhi. Under its Annual Action Plan 2019-20, all the districts of Odisha have been taken up for the survey. This Brief Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of Bargarh district covers various parameters like socio-economic indicators, present industrial structure of the district, and availability of industrial clusters, problems and prospects in the district for industrial development with special emphasis on scope for setting up of potential MSMEs. The report provides useful information and a detailed idea of the industrial potentialities of the district. I hope this Brief Industrial Potentiality Survey Report would be an effective tool to the existing and prospective entrepreneurs, financial institutions and promotional agencies while planning for development of MSME sector in the district. I would like to place on record my appreciation for Shri Jagadish Sahu, AD (EI) of this Institute for his concerted efforts to prepare this report for the benefit of entrepreneurs and professionals in the state. -

JEEBIKA Nuapada District During Their Visit to the 15Th National Youth 02.02.2010 at NASC, New Delhi

Director, OWDM visits Kandhamal: New PD in Watersheds, Nuapada: EVENTS AND NEWS Mr. Susanta Kumar Mallick, M.Sc (Ag) joined Onion Growers’ Co-op. Society Inaugurated: New Collector in Bargarh: as Project Director I/c, Sri Bhabagrahi Mishra, O.A.S joined as the Collector and Watersheds, Nuapada on Watershed Mission Leader, Bargarh on 08.02.2010 by taking 14th Jan, 2010. Earlier over charge from Sri Suresh Prasad Padhy who retired as working in several Collector Bargarh on 15.01.2010. The Project Director, capacities he has proven Watersheds, Bargarh welcomed and apprised him of the efficiency in implementing ongoing watershed projects in the district. watershed projects under various Government schemes. Under his leadership the Use of High Science Tools in IWMP Workshop watersheds development programme of the district is WESTERN ORISSA RURAL LIVELIHOODS PROJECT in New Delhi: expected to get a good mileage. Sri Sailendra Narayan Naik, Project Director, Watersheds, Sri G.B Reddy, IFS, Director OWDM, visited Kilabadi Micro Nuapada Watershed members’ exposure: Jan.-Feb., 2010, No.23 Bargarh participated in the workshop on “Use of High Science Watershed Project under DPAP- 8th batch on 18.02.2010 to 92 poor and very poor youths from watershed villages of Tools in IWMP” organized by ICRISAT, Hyderabad on 01- review the progress of watershed works and JEEBIKA Nuapada district during their visit to the 15th National Youth 02.02.2010 at NASC, New Delhi. activities in the district. He interacted with SHG and FIG Festival 2010 from 8th to 12th Jan10 at Bhubaneswar, had Members of Kilabadi micro watershed with PD, Watersheds, Office of Maa Bastarni Onion Growers Cooperative Society Bargarh PRI Members visit BAIF: exposures to different activities and institutes like mushroom CBT- NRM, and CBT- Monitoring and Evaluation, Kandhamal. -

The Role of Sambalpuri Handloom in the Economic Growth of Bargarh Pjaee, 18 (1) (2021) District Odisha

THE ROLE OF SAMBALPURI HANDLOOM IN THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF BARGARH PJAEE, 18 (1) (2021) DISTRICT ODISHA THE ROLE OF SAMBALPURI HANDLOOM IN THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF BARGARH DISTRICT ODISHA Kunal Mishra, Dr. Tushar Kanti Das, Research Scholar, Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration and Department of Business Administration Management, and Management, Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar, Burla Sambalpur University, Jyoti Vihar, Burla E mail id: [email protected] E mail id: [email protected] Kunal Mishra, Tushar Kanti Das, THE ROLE OF SAMBALPURI HANDLOOM IN THE ECONOMIC GROWTH OF BARGARH DISTRICT ODISHA-Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(1), ISSN 1567-214x Abstract: When Human Beings civilized, handloom has been an integral part of men. In this sense handloom has been an oldest industry of the world. From ancient period to the modern period handloom industry is closely connected with the economic growth of the land. So to say the Handloom Industry has a major role in the economic growth of India also. India has a rich, diverse and unique handloom tradition since long. History speaks that, weaving has been an extremely developed craft since Indus Valley Civilisation. From Historical records it is evident that, India is a country where dyeing, printing and embroidering has been a continuing process. The array of handloom textiles varies in different regions of India because of its Geography, Climate, Local Culture, Social Customs and availability of raw materials. A number of raw materials like cotton, silk, jute and bamboo etc. are used for creating fabrics in India. But silk and cotton predominates the Indian weaving tradition. -

Handloom in Odisha: an Overview

AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 HANDLOOM IN ODISHA: AN OVERVIEW Shruti Sudha Mishra* ICSSR Doctrol Fellow, Dept. of Business Administration, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India. [email protected] Dr. A. K. Das Mohapatra** Professor Dept. of Business Administration, Sambalpur University, Odisha, India. [email protected] Volume 8, Issue 8, 2020 http://aegaeum.com/ Page No: 134 AEGAEUM JOURNAL ISSN NO: 0776-3808 HANDLOOM IN ODISHA: AN OVERVIEW Abstract Handloom is an ancient cottage industry. In Odisha hand-woven fabrics have existed since beyond the reach of memory. This sector involves large number of artisans from rural and semi-urban areas, most of which are women and people from economically disadvantaged groups. Some of the strengths of this industry are availability of cheap and abundant labour, use of local resources, low capital investment, unique craftsmanship in manufacturing of the products and increasing appreciation by international consumers. It is important to note that despite such unique characteristics, the industry comprises a meager proportion of Indian exports in global market, thus calling for efforts to promote and channelize the offerings of the industry to tap its hidden potential. Therefore the present study has been undertaken with an aim to discuss the history of handloom in context to Odisha, its cultural importance, and contribution of handloom to the economic development of the weaving community of Odisha. Keywords: Odisha, handloom, weavers, economic development ***** 1: Introduction The glory and cultural vastness of Indian handloom industry has always been a topic of great discussion. Among all the beautiful handlooms having their regional importance, Odisha handloom is the one chosen for the present study. -

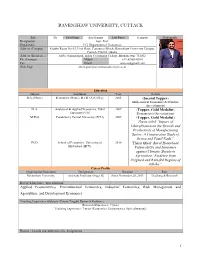

Ravenshaw University, Cuttack

RAVENSHAW UNIVERSITY, CUTTACK Title Dr. First Name Asis Kumar Last Name Senapati Photograph Designation Asst. Prof. Department P.G. Department of Economics Address (Campus) Faculty Room No-03, First Floor, Commerce Block, Ravenshaw University Campus, Cuttack-753003, Odisha Address (Residence) At/Po: Sisupalagarh, Indira Co-housing Colony, Bhubaneswar-751002 Ph. (Campus) Mobile +91-8908348951 Fax Email [email protected] Web-Page [email protected] Education Subject Institution Year Details B.A. (Hons.) Economics (Hons.), B.J.B. (A) College 2005 (Second Topper) Mathematical Economics & Statistics (Specialization) M.A. Analytical & Applied Economics, Utkal 2007 (Topper, Gold Medalist) University (UU) Econometrics (Specialization) M.Phil. Pondicherry Central University (PCU) 2009 (Topper, Gold Medalist) Thesis titled “Impact of Liberalization on the Growth and Productivity of Manufacturing Sector: A Comparative Study of Orissa and Tamil Nadu”. Ph.D. School of Economics, University of 2018 Thesis titled” Rural Household Hyderabad (HCU) Vulnerability and Insurance against Climatic Shocks in Agriculture: Evidence from Irrigated and Rain-fed Regions of Odisha”. Career Profile Organisation/Institution Designation Duration Role Ravenshaw University Assistant Professor (Stage II) Since November 28, 2013 Teaching & Research Research Interests / Specialization Applied Econometrics, Environmental Economics, Industrial Economics, Risk Management and Agriculture, and Development Economics Teaching Experience (Subjects /Course Taught) Research Guidance Research Experience: 7 years Teaching Experience: 7 years (Economics/ Econometrics (Specialization)) Honors / Awards and Administrative Assignments 1 1. Awards: Gold Medalist both in M.A. and M.Phil level 2. Research Fellowships: UGC-JRF Twice in 2008, and 2009, UGC, New Delhi 3. International Fellowships Awarded: Nil 4. Visiting Lecturer Title: “Heteroscedasticity Problem and Practical Session”, The Indian Econometric Society 5. -

The Padampur Sub-Division in Bargarh District of Orissa and Agalpur Block in Bolangir District Are Perennially Drought-Prone Areas

Title: Need to accord clearance to Aung Dam Project of Orissa and also to provide adequate funds for quick execution of work. SHRI PRASANNA ACHARYA (SAMBALPUR): The Padampur sub-Division in Bargarh district of Orissa and Agalpur Block in Bolangir district are perennially drought-prone areas. The Padampur sub-Division is adjacent to the KBK districts. There is no major or medium irrigation scheme in the area even after 52 years of Independence, although a number of rivers are flowing through this area. Keeping in view the acute water problem, the Government of Orissa had initiated a scheme for a river dam in the river Aung which originates in Madhya Pradesh and flows through this area of Orissa. This is known as the Aung Dam project. Strangely, this project has been lying without sanction of the concerned Ministry for the last several decades on many pretexts. If this project, which would be a major irrigation project, materialises, more than 50,000 hectares of agricultural land will get irrigation facilities. This sub-Division, which is a backward area in the State, having majority of the population of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, is not having a single industry and primarily the people depend on agriculture. The Aung Dam project, if executed, will change the whole economy of the area which would be a major boost for the economic development of the State as a whole. I would, therefore, urge upon the Union Government to accelerate the process of giving clearance to this project and to provide necessary funds for quick execution of work. -

Polio Vaccination Centers for International Travelers Travelling to Polio Endemic Countries Odisha Telephone Number of S.No

Polio Vaccination Centers for International Travelers travelling to Polio endemic countries_Odisha Telephone number of S.No. Name of district/urban area Name and address of designated OPV vaccination centre designated OPV vaccination Name of designated officials centre PPC Angul, C/O CDMO Office Angul, DHH Campus, Nr. Bus Stand, 1 Angul 9437498029 (HWM) Dr. Shantilata Das AT.PO. Angul-759122 2 Balasore PPC Balasore, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, At/po- Balasore 9937524994 Dr. Minakshi Mohanty 3 Bargarh PPC, Bargarh, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, Bargarh 9439981529 Dr. Narayana Prasad Mishra 4 Bhadrak PPC, Bhadrak, At- Kuanasa, Po/ Dist- Bhadrak-756100 9439402879 Dr. Minatilata Das 5 Bolangir PPC, Bolangir, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, Bolangir 9437900977 Dr. Subash Chandra Dash 6 Boudh PPC, Boudh, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, Boudh 9439991013 Dr. Sunil Kumar Behera 7 Cuttack City Hospital PP Center, Cuttack 9437026680 Dr. Abhay Kumar Pattnaik 8 Deogarh PPC DHH, Deogarh 9437879979 Dr. Gangadhar Pradhan 9 Dhenkanal PPC DHH, Dhenkanal 9439188008 Dr. Deepak Kumar Dehury 10 Gajapati PPC Parlakhemundi, Gajapati 9437381964 Dr. Suchitra Sahoo 11 Ganjam PPC City Hospital, Berhampur 6802224409 Dr. Sitansu Satpathy PPC, Jagatsinghpur, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, 12 Jagatsinghpur M- 9439992016, LHV, PPC) Dr. Sukant Kumar Dalaei Jagatsinghpur PPC Jajpur, District Headquarters, Hospital Campus, At/po- Jajpur Town, 13 Jajpur 9437027002 Dr.Nagen Mohapatra Jajpur PPC Jharsuguda, DHH Campus, Mangalbazar Road, Jharsuguda- 14 Jharsuguda 9438771375 Dr. Deepak Kumar Tripathy 768201 15 Kalahandi PPC Bhawanipatna, Kalahandi, Odisha 9437105045 Dr. Puspansu Sahu 16 Kandhamal PPC Phulbani 9438342340 Dr. Indra Mohan Chhatoi PPC Kendrapara, District headquarters, Hospital Campus, At/po- 17 Kendrapara 9438700607 Dr. -

Renovation of Progeny Orchard Paikamal, Padampur

DETAILED PROJECT PROPOSAL FOR RENOVATION OF PROGENY ORCHARD - PAIKMAL IN PADAMPUR SUB ‐ DIVISION OF BARGARH DISTRICT (ODISHA) PREPARED BY: ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE, PADAMPUR PROJECT PROPOSAL AT A GLANCE (Executive Summary) NAME OF THE PROJECT RENOVATION OF P.O. PAIKMAL PROPOSED WORK RENOVATION OF P.O. PAIKMAL PROJECT AREA PROJENY ORCHARD, PAIKMAL PROJECT DURATION 1 YEAR SOURCE OF THE FUND RASTRIYA KRUSHI VIKAS YOJNA PROJECT COST RS 59,00,000.00 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE, PADAMPUR EXECUTING AGENCY ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF HORTICULTURE PADAMPUR PROJECT PROPOSAL FOR RENOVATION OF P.O. PAIKMAL IN PADAMPUR SUBDIVISION OF BARGARH DISTRICT CONTEXT & BACKGROUND: Odisha is the 10th largest and 11th populous state accounting for about 5% of the geographical area and 4% of the population of the country. It has about 64 Lac ha i.e. about 40% of the land fit for agriculture. Agriculture provides directly or indirectly employment to about 64% of the total population contributing about 28% of the net state domestic product. Kharif is the main cropping season and Paddy being the principal crop of the state. Food grains constitute about 76% of the gross cropped area and Paddy alone shares about 67% of all the food grain taken together. The average fertilizer consumption in the state is very low (54Kg/ha as against national average of 104 kg/ha. The state has a larger population of SC & ST. Bargarh District formed on the 1st April 1993 being divided from Sambalpur District. It is one of the illustrious District of Odisha. Bargarh District lies on the western most corner of Odisha between 20 degree 43’ to 21 degree 41’ north latitude and 82 degree 39’ to 83 degree 58’ east longitude.