Thoughts on First-Generation Internet Law, 57 Wash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orin2 Programming Guide PDF Download

ORiN 2 programming guide - 1 - ORiN2 Programming guide Version 1.0.19.0 June 18, 2019 [Remarks] Some items might not be installed depending on the package you have. ORiN Forum DENSO WAVE Inc. ORiN 2 programming guide - 2 - [Revision history] Date Version Content 2005-05-09 1.0.0.0 First edition. 2006-08-21 1.0.1.0 Add the way to register CAO RCW into GAC under .NET framework 2.0. 2007-04-23 1.0.2.0 ORiN Installer registers CAO and CaoSQL RCW into GAC. 2008-07-16 1.0.3.0 Add some descriptions 2009-06-12 1.0.4.0 Add Import and Export commands to save settings. 2009-07-31 1.0.5.0 Add the way to register CAO RCW into GAC under .NET framework 2.0. 2010-02-10 1.0.6.0 Add description on LabVIEW 2010-06-08 1.0.7.0 Add the way to confirm an installation state of ORiN2 SDK. 2011-04-27 1.0.8.0 Add a sample code in C#. 2011-12-22 1.0.9.0 Add an error code. 2012-07-10 1.0.10.0 Add an error code. 2012-08-24 1.0.11.0 Modify an error code 2012-09-07 1.0.12.0 Modify an error code 2014-01-20 1.0.13.0 Add an error code. Add an integration into Visual Studio 2014-09-22 1.0.14.0 Add an error code. 2015-11-04 1.0.15.0 Add SysLog output of CAO log. -

New Robot Strategy

New Robot Strategy Japan’s Robot Strategy - Vision, Strategy, Action Plan - The Headquarters for Japan’s Economic Revitalization 10/2/2015 Part I General Statement ................................................................................ 2 Chapter 1 Prologue ...................................................................................... 2 Section 1 Current situation surrounding “Japan as a robotics superpower” .................................................................................................. 2 Section 2 Drastic transformation of robots and Japan’s future .................. 4 Section 3 Goal of robot revolution ............................................................. 7 Chapter 2 Measures for realization of robot revolution ...............................11 Section 1 Robot creativity – Thorough reinforcement of robots in Japan .11 Section 2 Utilization and popularization of robots – “Daily life with robots” across Japan ........................................................................... 13 Section 3 Development and progress of robot revolution on global perspectives – Toward new advanced IT society .................... 16 Part II Action Plan: Five-year Plan ................................................................. 18 Chapter 1 Cross-Cutting Issues ................................................................. 18 Section 1 Establishment of "Robot Revolution Initiative (RRI)" ............... 18 Section 2 Technology development toward the next generation ............. 20 Section 3 Policy -

The Next Generation Communications Privacy Act

ARTICLE THE NEXT GENERATION COMMUNICATIONS PRIVACY ACT ORIN S. KERR† In 1986, Congress enacted the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) to regulate government access to Internet communications and records. ECPA is widely regarded as outdated, and ECPA reform is now on the Congressional agenda. At the same time, existing reform proposals retain the structure of the 1986 Act and merely tinker with a few small aspects of the statute. This Article offers a thought experiment about what might happen if Congress were to repeal ECPA and enact a new privacy statute to replace it. The new statute would look quite different from ECPA because overlooked changes in Internet technology have dramatically altered the assumptions on which the 1986 Act was based. ECPA was designed for a network world with high storage costs and only local network access. Its design reflects the privacy threats of such a network, including high privacy protection for real-time wiretapping, little protection for noncontent records, and no attention to particularity or jurisdiction. Today’s Internet reverses all of these assumptions. Storage costs have plummeted, leading to a reality of almost total storage. Even U.S.-based services now serve a predominantly † Fred C. Stevenson Research Professor, George Washington University Law School. This Article was supported by the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Foundation Program on Demography, Technology and Criminal Justice at the Law Library of Congress, where the Author presently serves as a Scholar in Residence. The Author thanks Richard Salgado, Chris Soghoian, Al Gidari, Jim Dempsey, Marc Zwillinger, Chris Yoo, Eric Goldman, Edward Felten, Ryan Calo, Andrea Matwyshyn, Jerry Kang, Ramesh Ponnuru, and Gail Kent for their helpful comments, as well as Cynthia Jordan, Robert Newlen, and David Mao at the Law Library of Congress for their support. -

Data Mining, Dog Sniffs, and the Fourth Amendment

DATA MINING, DOG SNIFFS, AND THE FOURTH AMENDMENT An algorithm, designed to probe a database containing all personal data available to the government, sees that you have recently bought some fertilizer and a large truck, and that you have emailed someone with a .lb (Lebanon) email address. Seeing this red flag pop up on his computer, a government agent pulls your bank records, your Amazon and iTunes purchases, the domain names that you’ve recently visited, and a list of everyone you have recently phoned or emailed. Inspecting all of these records, the agent determines that you were merely asking your Lebanese uncle for advice on expanding your farm and makes a notation in his database. (He is also able to determine your religious affiliation, that you have an affinity for Steven Seagal movies, and that you have been having an affair, but is less interested in all of that.) This example of “data mining” is the future, if not the present, of law enforcement.1 Data mining both offers enormous possibilities for law enforcement and national security — in the scenario above, the fertilizer and truck could have been intended for a far less innocuous use — and radically undermines the notion that one’s interests, affilia- tions, and legal activities can be kept private from the government. Such concerns have led to significant public debate over the proper scope of surveillance, prompted in particular by Edward Snowden’s recent disclosures. Yet despite the obvious privacy implications of data mining, tradi- tional Fourth Amendment doctrine offers relatively little to help con- strain such activity. -

Robotic Middlewares to the Physical Agent System

Layered Implementation of Robotic Middlewares to the Physical Agent System IROS’06 Workshop WS4 Robotics Standardization Makoto MIZUKAWA, Ph.D. [email protected] Shibaura Institute of Technology, Tokyo Chair ORiN Forum/JARA, Project Leader ISO TC184/SC2 RAPI Contact of OMG Robotics-DTF to ISO TC184/SC2 Oct. 10, 2006, International Conference Beijing, China on Iintelligent Robots and Systems 1 Outline Needs for standard Environment Physical Agent System Layered Implementation of Middlewares ORiN for Robot Collaboration LwRTC for Embedded controller Future work 2 Oct. 10, 2006, Beijing, China International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems Needs for standard Environment 3 Oct. 10, 2006, Beijing, China International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems Robotics in future Hazardous task Unmanned Autonomy substitute in fields systems Manufacturing High speed Human Industrial robots work /precision Human-Robot-Interaction Embedded/ Service robots Ubiquitous robots symbiosis Entertainment robots HouseholdHousehold Pet/Pet/ healinghealing WorkWork assistassist DailyDaily assistassist New media Communication media RescueRescue MedicalMedical 4 Oct.Daily 10, 2006, lifeBeijing, support China International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems I’REX2005 DAEJEON 5 Oct. 10, 2006, Beijing, China International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems Related Activities (examples) forfor TelecomTelecom forfor MfgMfg FIPAFIPA:The:TheFoundations Foundationsfor for IntellIntelligentigent ISOISO TC-1TC-18484,, -

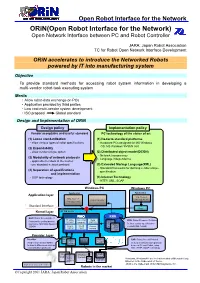

Orin(Open Robot Interface for the Network)の概要

Open Robot Interface for the Network ORiN(Open Robot Interface for the Network) Open Network Interface between PC and Robot Controller JARA: Japan Robot Association TC for Robot Open Network Interface Development ORiN accelerates to introduce the Networked Robots powered by IT into manufacturing system Objective To provide standard methods for accessing robot system information in developing a multi-vendor robot-task executing system Merits ・Allow robot-data exchange on PCs ・Application provided by third parties ・Low cost multi-vendor system development ・ISO proposal Global standard Design and Implementation of ORiN Design policy Implementation policy Vender acceptable and useful standard PC technology of the states of art (1) Loose standardization (1) De-facto standard platforms - allow various types of robot specifications - Hardware:PCs designed for MS Windows OS: MS Windows 95/98/NT4.0 (2) Expandability - allow vender unique option (2) Distributed object model(DCON) - Network transparency (3) Modularity of network protocols - Language independence - applicable to robots in the market - use standard network protocol (3) Extended Markup Language(XML) - Standard framework for defining vendor unique (4) Separation of specifications specification and implementation - OOP technology (4) Internet Technology - HTTP, XML, SOAP Windows PC Windows PC Application Application Application layer Mfg. System Mfg. System Motion Monitor management Management Standard Interface Proxy Kernel layer DCOM Server RAO RRD RAO: Robot Access Object Provider Correction Data RRD: Robot Resource Definition Provides the unified access mngmnt mngmnt caching B Co. Defines vendor specific robot method to robot data based on robotA Co. Async. Event models(XML format) DCON Access modelrobot control report logging model Provider layer Provider B Co. -

It's Too Complicated: How the Internet Upends Katz, Smith, and Electronic

Harvard Journal of Law & Technology Volume 30, Number 1 Fall 2016 IT’S TOO COMPLICATED: HOW THE INTERNET UPENDS KATZ, SMITH, AND ELECTRONIC SURVEILLANCE LAW Steven M. Bellovin, Matt Blaze, Susan Landau, & Stephanie K. Pell* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 2 II. LEGAL BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS ........................................... 11 A. Content/Non-Content Constitutional Distinctions & Statutory Definitions ................................................................ 12 B. What Other Scholars Have Said and Done ................................ 20 1. To Distinguish and Categorize or Not? ................................... 21 C. Third Party Doctrine Complications ......................................... 22 1. United States v. Warshak......................................................... 22 2. Miller & Smith ......................................................................... 25 III. NETWORK ARCHITECTURES ......................................................... 32 A. The Phone Network and the Internet .......................................... 34 B. An Introduction to the Network Stack ........................................ 36 C. Architectural Content ................................................................. 44 D. Defining DRAS ........................................................................... 46 IV. INTERNET SERVICES AND METADATA .......................................... 52 A. Services and Architecture .......................................................... -

Interpreting Access and Authorization in Computer Misuse Statutes

ARTICLES CYBERCRIME'S SCOPE: INTERPRETING "ACCESS" AND "AUTHORIZATION" IN COMPUTER MISUSE STATUTES ORIN S. KERR* The federal government, all fifty states, and dozens of foreign countries have enacted computer crime statutes that prohibit "unauthorizedaccess" to computers. No one knows what it means to "access" a computer, however, or when access becomes "unauthorized." The few courts that have construed these terms have offered widely varying interpretations. Several recent decisions suggest that any breach of contract renders an access unauthorized, broadly criminalizing contract law on the Internet. In this Article, Professor Orin Kerr explains the origins of unauthorized access statutes, and examines why the early beliefs that such statutes articulated a clear standard have proven remarkably naive. He then shows how and why the courts have construed these statutes in an overly broad manner that threatens to criminalize a surprising range of innocuous conduct involving com- puters. Finally, Professor Kerr offers a normative proposal for interpreting "access" and "authorization." Courts should reject a contract-based theory of authorization,and should limit the scope of unauthorized access statutes to circum- vention of code-based restrictions on computer privileges. This proposed interpre- tation best mediates between securing privacy and protecting the liberty interests of Internet users. It also mirrors criminal law's traditional treatment of consent defenses, and avoids possible constitutional difficulties that may arise under the broader constructions that courts have recently favored. INTRODUCTION Justice Holmes once noted that when a legislature enacts a new crime, "it is reasonable that a fair warning should be given to the world in language that the common world will understand, of what the law intends to do if a certain line is passed. -

Orin2 SDK User's Guide Version 2.1.50

ORiN2 SDK user's guide - 1 - ORiN2 SDK User's guide Version 2.1.50 April 28, 2020 【Remarks】 ORiN Forum DENSO WAVE Inc. ORiN2 SDK user's guide - 2 - 【Revision history】 Date Version Content 2006/02/24 1.0 First edition. 2006/08/11 1.0.1 A runtime version and sample providers (b-CAP, NS300) were added. 2006/10/02 1.0.2 Supported OS were described. 2006/12/15 1.0.3 Sample providers (Joystick, Timer, RCB-1) were added. 2007/04/20 2.0.5 Sample providers (FIT, IFS, VBP) were added. 2007/07/02 2.0.6 b-CAP provider was added also in the ‘Evaluation’ installer. 2007/11/13 2.0.7 CaoSQL was added also in the ‘Bundle’ installer. 2008/01/08 2.0.8 All binary modules were added in the ‘Runtime’ installer. 2008/03/24 2.0.9 Sample providers (VB Gateway, VPS, OpenCV) were added. 2008/06/19 2.0.10 Sample providers (Genie, AIO) were added. 2008/07/01 2.0.11 Sample providers (Dummy) were added. 2008/07/11 2.0.12 Sample providers (anyfeed, SSTCCS, SSTDN3) were added. 2009/03/12 2.1.0 Start menu and folder structures were changed. DirectShow provider was added. 2009/06/12 2.1.1 b-CAP provider was added also in the ‘Bundle’ installer. 2010/03/04 2.1.2 Sample providers (HALCON, LINX GINGA board,TAIYO servo hand) were added. 2010/09/27 2.1.3 “How to check the installation state of ORiN2 SDK” was added. Some provider samples are added. -

Self-Driving Safety Report Our Mission

SELF-DRIVING SAFETY REPORT OUR MISSION We believe that the next generation of transportation is autonomous. From shared and personal vehicles, to long- and short-distance travel, to delivery and logistics, autonomy will “Safety is the most important aspect of a self-driving vehicle. NVIDIA’s creation of a safe fundamentally improve the way the self-driving platform is one of our greatest world moves. At NVIDIA, our automotive endeavors, and provides a critical ingredient team’s mission is to develop self-driving for automakers to bring autonomous technology that enables safer, less vehicles to market.” congested roads and mobility for all. Jensen Huang NVIDIA founder and CEO CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 ON-ROAD TESTING 12 THE DRIVE FOR AUTONOMOUS VEHICLE SAFETY 13 THE FOUR PILLARS OF SAFE AUTONOMOUS DRIVING 2 CYBERSECURITY 14 DEVELOPER TRAINING AND EDUCATION 14 1. ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION PLATFORM 3 2. DEVELOPMENT INFRASTRUCTURE THAT SUPPORTS DEEP LEARNING 4 SUMMARY 15 3. DATA CENTER SOLUTION FOR ROBUST SIMULATION AND TESTING 4 4. BEST-IN-CLASS PERVASIVE SAFETY PROGRAM 5 APPENDICES 16 ARCHITECTED FOR SAFETY 7 ACRONYMS 16 REFERENCES HARDWARE 8 16 SOFTWARE 9 VEHICLES & SENSORS 9 DATA CENTER 10 MAPPING 10 SIMULATION 11 REPLAY 11 core architecture. The same strategy holds for safety. Our architecture enriches the overall INTRODUCTION system with elements that consistently improve safety. NVIDIA has created essential technologies for building robust, end-to-end systems for the research, development, and deployment of self-driving vehicles, spanning from the data center to the edge. We offer a range of hardware and software solutions, from powerful GPUs and servers to a complete AI training infrastructure and in-vehicle autonomous driving supercomputers. -

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and the 116Th Congress

Cybercrime and the Law: Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) and the 116th Congress September 21, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46536 SUMMARY R46536 Cybercrime and the Law: Computer Fraud and September 21, 2020 Abuse Act (CFAA) and the 116th Congress Peter G. Berris The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), 18 U.S.C. § 1030, is a civil and criminal Legislative Attorney cybercrime law prohibiting a variety of computer-related conduct. Although sometimes described as an anti-hacking law, the CFAA is much broader in scope. Indeed, it prohibits seven categories of conduct including, with certain exceptions and conditions: 1. Obtaining national security information through unauthorized computer access and sharing or retaining it; 2. Obtaining certain types of information through unauthorized computer access; 3. Trespassing in a government computer; 4. Engaging in computer-based frauds through unauthorized computer access; 5. Knowingly causing damage to certain computers by transmission of a program, information, code, or command; 6. Trafficking in passwords or other means of unauthorized access to a computer; 7. Making extortionate threats to harm a computer or based on information obtained through unauthorized access to a computer. Since the original enactment of the CFAA in 1984, technology and the human relationship to it have continued to evolve. Although Congress has amended the CFAA on numerous occasions to respond to new conditions, the rapid pace of technological advancement continues to present novel legal issues under the statute. For example, with increasing computerization has come a corresponding proliferation of Terms of Service (ToS) agreements—contractual restrictions on computer use. -

50 Years of Innovation

50 YEARS OF INNOVATION DENSOROBOTICS-EUROPE.COM European Headquarters: Telephone: Commercial information email: DENSO Robotics Europe +49 (0) 6105 27 35 150 [email protected] (DENSO EUROPE B.V.) Waldeckerstr. 9 Telefax: Technical support email: 64546 Moerfelden-Walldorf +49 (0) 6105 27 35 180 [email protected] Germany Watch our latest videos Your Area Dealer DENSO - Inventor of the QR Code DENSORoboticsEurope DENSORoboticsEurope DENSORoboticsEU denso-robotics-europe DENSO_Robotics_EU_2018_V1_EN NOTE: The information contained in this brochure is intended for reference purposes only and is subject to change without prior notice. Please contact us for additional information. DENSO Robotics DENSO Robotics INNOVATION IS IN OUR DNA DENSO CORPORATION AT A GLANCE* Our story began in 1949 when Nippondenso Co. Ltd. (today DENSO), a separate entity from Toyota Motor Co. Ltd., was established. $40.4b 154,000 in annual employees in 200 revenue (USD) group companies OUR BUSINESS FIELDS 9% QR Code of revenue invented in re-invested in R&D 1994 *Data as of March 31st, 2017. ROBOTICS PIONEER One of TOP 3 auto parts suppliers worldwide 50 years 100,000 robots Automotive Consumer Products Over 50 Years Developing Worldwide Market Leader Industrial Robots With over 100,000 DENSO robots Since 1967 we are developing we are the market leaders in small robots for our automotive industry. industrial robots. OEM supplier 20,000 own use Micro Grid, Electric Power Assist, Security, Healthcare, Biotechnology, Agriculture Support, Cold Chain, Trusted OEM Robot Supplier One of the World’s Largest Community Network Solution Business Companies around the world trust in Robot Users the quality of our products.