A Dress Rehearsal for Night Baseball

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A3365 Publication Title: Lists of Aliens Arriving at Brownsville, Del Rio

Publication Number: A3365 Publication Title: Lists of Aliens Arriving at Brownsville, Del Rio, Eagle Pass, El Paso, Laredo, Presidio, Rio Grande City, and Roma, Texas, May 1903-June 1909, and at Aros Ranch, Douglas, Lochiel, Naco, and Nogales, Arizona, July 1906-December 1910 Date Published: 2000 LISTS OF ALIENS ARRIVING AT BROWNSVILLE, DEL RIO, EAGLE PASS, EL PASO, LAREDO, PRESIDIO, RIO GRANDE CITY, AND ROMA, TEXAS, MAY 1903-JUNE 1909, AND AT AROS RANCH, DOUGLAS, LOCHIEL, NACO, AND NOGALES, ARIZONA, JULY 1906-DECEMBER 1910 Introduction On the five rolls of this microfilm publication, A3365, are reproduced manifests of alien arrivals in the INS District of El Paso, Texas. Specifically, it includes arrivals at El Paso, Texas, from May 1903 to June 1909; arrivals at Brownsville, Del Rio, Eagle Pass, Laredo, Presidio, Rio Grande City, and Roma, Texas, from July 1906 to June 1909; and arrivals at Aros Ranch, Douglas, Lochiel, Naco, and Nogales, Arizona, July 1906–December 1910. Arrangement is chronological by year, then roughly chronological by quarter year, then by port of arrival. These records are part of the Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Record Group (RG) 85. Background Early records relating to immigration originated in regional customhouses. The U.S. Customs Service conducted its business by designating collection districts. Each district had a headquarters port with a customhouse and a collector of customs, the chief officer of the district. An act of March 2, 1819 (3 Stat. 489) required the captain or master of a vessel arriving at a port in the United States or any of its territories from a foreign country to submit a list of passengers to the collector of customs. -

![1914-01-05 [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5784/1914-01-05-p-135784.webp)

1914-01-05 [P ]

'* *'V";t'ivv -»r p - »«^ rtr< " <a <* „ *,,, tJI '' ,v * < t lllSIlISi 'v 1 ' & * * . o * * . - *• , - >*-'. V s. 5 1 ....'.:?v>;^ »5v ' ^ y.h--- y< IE EIGHT. • A..•'•:•' '.,4 .•*, ,"*,.- -vs'. * f« THE EVENING TIMES. GRAND FORKS, N. D. MONDAY, JANUARY 5, IMS. I*' Winter News and Gossips^Wor ort ML HtSOT "™* and Knobs—-At Last Hank Sees a Chance to Get Some Easy Money By Farren •ee.BUT this is rTHCRE'S 6EEM V<HV ^»U rmtTu.t * RftTTON RiDttf, toy A V4RE.C*.! HAT HEM) Mt,H<o8V, H6, Mts. I M ALMOiT TRAIN , fc MKH CMi'T HAVE. TWG. SURE THEY . t *•$<> ,v, HAVt A SLEEP VlflTHCUT TW5TWM OFFICIALS OF- I DON'T P«SS»TtV£ n ^ ? N H lL BE MIEN HAVENT G36T — WHY? BEIN' WWEO BV WE. MtAM VJR£CK?I BOWPEP TOE R0«> «*• THNK. s Mmpin AND — I k»TV A the mict 66-/ HERE NCT? • • • if rtant Meeting of Na- eoT went w ? ft*RiADY Inal Commission and IN&PECIIOlt |aternity Committee ERS' DEMANDS iRE TO BE HEARD _ i lent Fultz of the Fed- j £ lion is Confident They Will Succeed. ! mia.ti. .Inn. -Tin- .1 rriwd storduj i'f I'resident 1 >;in .I'din- the American league, Neerr- I111 Heydler of the National and r.nrney I > r< • >•1"i 1:-;s. prer-d- JESS WILLARD THINKS HE'LL SOON BE HEAVYWEIGHT CHAMP tlio I'ii tsiiurgli club «'f the |al league. is forerunner cling ill" tin' lint iimal baseball Ission tii'i'r today tint bids fair »o baseball history. MATTER OF os the initial appeaianee 011 TOWARD FEDERALS tional commission of John K. -

Specimen List.Xlsx

Bird - Egg - Nest Salvage List Specimens from Sierra Foothills Audubon Society to Nevada County Resource Conservation District for Display and Education Purposes Band-tailed Pigeon Patagioenas fasciata (mounted) Barrows Goldeneye Bucephala islandica (mounted) Belted Kingfisher Megaceryle alcyon (mounted) California Gull Larus californicus (mounted) Common Tern Sterna hirundo (mounted) Fox Sparrow Passerella iliaca (mounted) Northern Flicker Colatpes auratus (mounted) Snow Goose Chen caerulescens (mounted) Western Screech Owl Megascops kennicottii (mounted) Wood Duck Aix sponsa (mounted) Collection by Emerson Austin Stoner, donated to Sierra Foothills Audubon Society Emerson Austin Stoner June 27, 1892 Des Moines, Iowa - March 9, 1983 Vallejo, California Mr. Stoner’s family moved to California from Iowa in 1914 where Mr. Stoner attended Healds Business College in Oakland. He then moved to Benicia, California where he served in the Finance & Accounting Department of the Benicia Arsenal, ultimately retiring as Chief Financial Officer in 1957 after 40 years. Mr. Stoner was a natural history enthusiast with particular interest in birds, authoring numerous articles for scientific magazines and newspapers, banding birds, collecting specimens, etc. Mr. Stoner collected specimens from the age of 14 until the age of 85 - over 70 years. 1906 to 1910 - Des Moines, Iowa #1 Eastern Robin Turdus migratorius migratorius (8 eggs - May 1906 to May 1909) #2 Blue Jay Cyanocitta cristata bromia (18 eggs - May 1906 to June 1908) #2a Northern Flicker Colaptes -

National League News in Short Metre No Longer a Joke

RAP ran PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY 11, 1913 CHARLES L. HERZOG Third Baseman of the New York National League Club SPORTING LIFE JANUARY n, 1913 Ibe Official Directory of National Agreement Leagues GIVING FOR READY KEFEBENCE ALL LEAGUES. CLUBS, AND MANAGERS, UNDER THE NATIONAL AGREEMENT, WITH CLASSIFICATION i WESTERN LEAGUE. PACIFIC COAST LEAGUE. UNION ASSOCIATION. NATIONAL ASSOCIATION (CLASS A.) (CLASS A A.) (CLASS D.) OF PROFESSIONAL BASE BALL . President ALLAN T. BAUM, Season ended September 8, 1912. CREATED BY THE NATIONAL President NORRIS O©NEILL, 370 Valencia St., San Francisco, Cal. (Salary limit, $1200.) AGREEMENT FOR THE GOVERN LEAGUES. Shields Ave. and 35th St., Chicago, 1913 season April 1-October 26. rj.REAT FALLS CLUB, G. F., Mont. MENT OR PROFESSIONAL BASE Ills. CLUB MEMBERS SAN FRANCIS ^-* Dan Tracy, President. President MICHAEL H. SEXTON, Season ended September 29, 1912. CO, Cal., Frank M. Ish, President; Geo. M. Reed, Manager. BALL. William Reidy, Manager. OAKLAND, ALT LAKE CLUB, S. L. City, Utah. Rock Island, Ills. (Salary limit, $3600.) Members: August Herrmann, of Frank W. Leavitt, President; Carl S D. G. Cooley, President. Secretary J. H. FARRELL, Box 214, "DENVER CLUB, Denver, Colo. Mitze, Manager. LOS ANGELES A. C. Weaver, Manager. Cincinnati; Ban B. Johnson, of Chi Auburn, N. Y. J-© James McGill, President. W. H. Berry, President; F. E. Dlllon, r>UTTE CLUB, Butte, Mont. cago; Thomas J. Lynch, of New York. Jack Hendricks, Manager.. Manager. PORTLAND, Ore., W. W. *-* Edward F. Murphy, President. T. JOSEPH CLUB, St. Joseph, Mo. McCredie, President; W. H. McCredie, Jesse Stovall, Manager. BOARD OF ARBITRATION: S John Holland, President. -

Inventory of Records of the Department of Health

Inventory of Records of the Department of Health August, 2004 Hawaii State Archives Iolani Palace Grounds Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Table of Contents Department of Health (Administrative History) .........................................................1 Board of Health Board of Health (History) ..................................................................................3 Record Series Descriptions Minutes, 1858-1983 (Series 259) ...........................................................5 Container List.........................................................................C-1 Outgoing Letters, 1865-1918 (Series 331).............................................6 Container List ......................................................................C-30 Incoming Letters, (1850-1904)-1937 (Series 334) ................................8 Container List.......................................................................C-35 Correspondence, (1905-1913)-1917 (Series 335) ..................................9 Container List.......................................................................C-49 Correspondence of the Secretary, 1925-1980 (Series 324) .................10 Container List.......................................................................C-15 Report on Hawaiian Herbs, 1917-ca. 1921 (Series 336) .....................11 Container List.......................................................................C-64 Physician’s Licensing Records, 1890-1969 (Series 502) ....................12 Container List.......................................................................C-75 -

Finding Aid for the Andrew Brown &

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives (MUM00046) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives (MUM00046). Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, University of Mississippi. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Andrew Brown & Son - R.F. Learned Lumber Company/Lumber Archives MUM00046 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACCESS RESTRICTIONS Summary Information Open for research. This collection is stored at an off- site facility. Researchers interested in using this Historical Note collection must contact Archives and Special Collections at least five business days in advance of Scope and Contents Note their planned visit. Administrative Information Return to Table of Contents » Access Restrictions Collection Inventory Series 1: Brown SUMMARY INFORMATION Correspondence. Series 2: Brown Business Repository Records. University of Mississippi Libraries Series 3: Learned ID Correspondence. MUM00046 Series 4: Learned Business Records. Date 1837-1974 Series 5: Miscellaneous Series. Extent 117.0 boxes Series 6: Natchez Ice Company. Abstract Series 7: Learned Collection consists of correspondence, business Plantations records, various account books and journals, Correspondence. photographs, pamphlets, and reports related to the Andrew Brown (and Son), and its immediate successor Series 8: Learned company, R.F. -

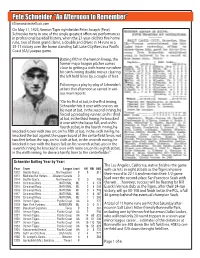

Pete Schneider

Pete Schneider, “An Afternoon to Remember” ©DiamondsintheDusk.com On May 11, 1923, Vernon Tiger rightfielder Peter Joseph (Pete) Schneider turns in one of the single greatest offensive performances in professional baseball history, when the 27-year-old hits five home runs, two of them grand slams, a double and drives in 14 runs in a 35-11 victory over the home standing Salt Lake City Bees in a Pacific Coast (AA) League game. Batting fifth in the Vernon lineup, the former major league pitcher comes close to getting a sixth home run when his sixth-inning double misses clearing the left field fence by a couple of feet. Following is a play-by-play of Schneider’s at bats that afternoon as carried in vari- ous news reports: “On his first at bat, in the first inning, Schneider hits it over with one on; on his next at bat, in the second inning, he forced a preceding runner; on his third at bat, in the third Inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; and on his fourth at bat, in the fourth inning, he knocked it over with two on; on his fifth at bat, in the sixth inning, he knocked the ball against the upper board of the centerfield fence, not two feet below the top; on his sixth at bat, in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; on his seventh at bat, also in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with none on; on his eighth at bat, in the ninth inning, he drove a terrific liner to the centerfielder.” Schneider Batting Year by Year: The Los Angeles, California, native finishes the game Year Team League Level HR RBI AVG with six hits in eight at bats as the Tigers improve 1912 Seattle Giants ..................... -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1939-08-11

IT 10, 1939 - Ar~hery Cloudy, Warmer IOWA-Partly doudy, _what Prof. A. S. GllJene Annoaneea warmer 111 west and north today: Procram for State Meet Here tomorrow fair, wanner 111 extreme (Bee 8tor" Pap .) °t DaiI» nonbeaA Days "oUJa City'. II ornin, NSUJ.paper FIVE CENTS IOWA CITY, IOWA FRIDAY, AUGUST 11, 1939 VOLUME XXXVDI NUMBER 172 Tornadoes, Cloudbursts Furnishes Roosevelt Will Have No Part Blood Walter Rhodes Aids Lash Sections of Iowa, Fellow Prisoner In ~Democratic Suicide,' Should With Transfusion FT. MADISON, Aug. 10 (AP) Cause Injury, Damage Blood from the veins of Walter Party Nominate Conservatives Rhodes, convicted of murder, for slaying his wife, tonight was help Iowa Farmers Foresee Record Yield ing W. J. Fair of Marengo, a fel· Dramatic Photo of a Rescue on the High Seas Six Are Hurt; low inmate at the state prison, Conservatism In T~is Year's Corn Crop Harvest In his battle against leukemia,' Spencer. Gets a circulatory system disease. Spells Doom, DES MOINES, Aug. 10 (AP) were harvested in 1912 and 1920, Rhodes, w b 0 s e home was in Iowa's 200,000 farmers see in but they were 1 1·2 bushels an Iowa City, contributed his blood in He Declares 4.1-Inch Rain their rapidly maturing corn crop acre less than the current fore a 50-minute transfusion in the I'S best-knoWl! the prospect of harvesting a rec cast. }ranere, slunt ord average yield of 47 1-2 bush Leslie M. Carl, federal agricul penitentiary hospital here this af Lynch, auw Liberty Center, els an acre, the agriculture depart tural statistician, placed the Aug. -

The Crescent" Student Newspaper Archives and Museum

Digital Commons @ George Fox University "The Crescent" Student Newspaper Archives and Museum 6-1-1909 The Crescent - June 1909 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/the_crescent Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "The Crescent - June 1909" (1909). "The Crescent" Student Newspaper. 95. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/the_crescent/95 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Museum at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in "The Crescent" Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r4 t -1 11 I Ac) C) rr(J) m 6) z 2 -1 - -— THE CRESCENT. t40 Joe/al S/Fe Published Monthly during the college year by Student Body. WnioHT, ‘10, Editor.in-Chief. life is HARVEY A. Is of great importance to the student. Student NATHAN CooK, 91, Associate Editor. without it. Durring the college year LAURA E. HAMMER, ‘10 not complete EARL HENRY, ‘12 Locals numerous socials and “parties” are given. We have I OLIN C. HADLEY, Acad. CALKINS, ‘12, Exchanges planned for these and are able to furnish refreshments CLAuDE this, VICTOR HERs, ‘12, Business Manager. in an up.to-date and pleasing manner. Besides ClAuDE NEWLUc, ‘11, Asst. Business Manager. we are prepared to satisfy your desires with first-class Confectionery, Fruits, Nuts, etc. Give us a call. Terms, 75c. a Year in Advance. Single Copy lOc. I Entered as second-class matter at the Postoffice at Newberg, Ore. -

Mcpherson County Divorces 1871

McPherson County Divorces 1871 - 1917 LAST NAME HUSBAND WIFE DATE FILM# CASE # ALBRIGHT FREDERICK CATHERINE APRIL 1873 2296776 18 ALBRIGHT FREDRICK MARY JUNE 1875 2296776 80 ALLEN JOSEPH ELIZA FEB 1887 2296810 1521 ALMA HARRY MARIE MAY 1910 2296813 4901 ALTMAN SAMUEL IONE FEB 1913 2296813 5106 ANDERSON CLAUSE HILDA APR 1914 2296813 5215b ANDERSON WILLIAM H. ANN JUNE 1875 2296776 26 ANNIS WILLIAM LAVINIA MAY 1902 2296811 4325 BACON ALBERT MINNIE NOV 1900 2296811 4212 BAIRD ROBERT ELIZA JUNE 1909 2296812 4831 BALDWIN ROBERT MARY JUNE 1883 2296776 870 BALL PEMBROKE LIBBIE JAN 1901 2296811 4227 BALTZLEY CHARLES EMMA AUG 1886 2296810 1420 BANGSTON HENRY ESTELLA SEPT 1898 2296811 4037 BARNES CHARLES ROSA JAN 1883 2296776 718 BASIL JOHN IDA DEC 1903 2296812 4390 BECK JOHN EDITH OCT 1915 2296813 5335 BEERS A.R. MILLIE DEC 1909 2296813 4870 BERGGREN ANDREAS JOHANNA DEC 1887 2296810 1724 BIAS SYLVESTER MINNIE AUG 1886 2296810 1407 BIGFORD OREN SARAH DEC 1900 2296811 4162 BLUE A. LAVERGNE M. MAUDE OCT 1913 2296813 5171 BOLINDER NILS INGRILENA JAN 1892 2296811 3091 BOYCE FREDRICK NORA OCT 1899 2296811 4122 BRANTANO WILLIAM SARAH JAN 1882 2296776 583 BROWN A.J. SARAH OCT 1889 2296810 2148 BROWN ALLAN ANGIE OCT 1917 2296813 5512 BROWN PLEASANT LUTITIA NOV 1899 2296811 4131 BROWN W.A. ANNIE JAN 1916 2296813 5364 BRUCE C.A. HANNA MAR 1914 2296813 5209 BRUNDIN ALBERT HILMA JAN 1896 2296811 3703 BUCHHANAN JAMES MARY JUNE 1909 2296812 4808 BULL ROBERT CLARA MAR 1886 2296776 1377 BURNISON J.A. CHRISTINE OCT 1902 2296811 4351 BURNS JOEL CARRIE APR 1891 2296810 2806 BUSSIAN CHRIST CATHERINE FEB 1878 2296776 173 CALDWELL W.O. -

Emily Fish 1907-1909

Keeper's Log Pt. Pinos Lighthouse Emily A. Fish Principal Keeper Volume III 1907-1909 LOG OF POINT PINOS LIGHTHOUSE STATION - continued Jan.1907 1 Wind fresh to light NW Clear. St and schooner bd out in tow. Tug & schooner bd out. 2 light N Clear. 3 " SW Partly cloudy, rain .03 4 " " to fresh S to NW Rain .19 5 " " N to S Partly cloudy, frost, ice formed. Snow on the mountains. 6 " " to fresh SE Variable, rain .45. St bd out south. 7 S Variable, rain .78. Earthquake at about 11 P.M. 8 " S to NE Rain, ptly cloudy .32 II 9 " to fresh S to NE Rain, hail, thunder, lightning .64 Tug & tank schooner in port & bd out. 10 " to fresh S to NE Rain .17 11 " " to fresh NW Ptly clear. 12 " to strong squally SW Rain, hail, sleet .28 13 " to strong squally SW Rain, hail, sleet .52 Tug & vessel bd out. Ship bd in (the Marion Chilcott). 14 " to strong squally Rain, hail .27 15 " SW Clear. Tug & vessel bd in. Tug & ship bd out and return. 16 " variable SE SW Rain 2.20. Tug and ship bd out f return. 17 ,, variable SW to NE Shower, clear, frost .05. Tug & ship bd out. 18 ,, variable NE Clear. Tug & schooner bd out. 19 " NE Clear. LOG OF POINT PINOS LIGHTHOUSE STATION - continued Jan.1907 - cont'd 20 Wind light NE Clear. " 21 " NE Clear. 22 " " NE Partly clear, fog. Tug & schooner bd out. 23 " tt NE SW Cloudy, showers, .08. St bd in & out.