An Exalted Defeat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANKS and BANKING Notes, Acknowledgements of Advance, Residents

FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 34 • NUMBER 159 Wednesday, August 20,1969 • Washington, D.C. Pages 13403-13457 Agencies in this issue— Agricultural Research Service Atomic Energy Commission Civil Aeronautics Board Civil Service Commission Coast Guard Consumer and Marketing Service Customs Bureau Export Marketing Service Federal Aviation Administration Federal Communications Commission Federal Home Loan Bank Board Federal Maritime Commission Federal Power Commission Federal Reserve System Fish and Wildlife Service Food and Drug Administration Hazardous Materials Regulations Board Internal Revenue Service Interstate Commerce Commission Land Management Bureau National Commission on Product Safety Post Office Department Securities and Exchange Commission Small Business Administration Transportation Department Detailed list of Contents appears inside. Announcing First 10-Year Cumulation TABLES OF LAWS AFFECTED in Volumes 70-79 of the UNITED STATES STATUTES AT LARGE Lists all prior laws and other Federal in- public laws enacted during the years 1956- struments which were amended, repealed, 1965. Includes index of popular name or otherwise affected by the provisions of acts affected in Volumes 70-79. Price: $2.50 Compiled by Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration Order from Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 The F ederal R egister will be furnished by mail to subscribers, free of postage, for $2.50 per month or $25 per year, payable in advance. The charge for individual copies is 20 cents for each issue, or 20 cents for each group of pages as actually bound. Remit check or money order, made payable to the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

? ? Lower Town Harpers Ferry Trail Guide

LOWER TOWN HARPERS FERRY TRAIL GUIDE Visitor Center POTOMAC parking 2 miles Park Boundary S Harper h Cemetery Train e 24 n Church Street Station a Jefferson n d Rock o Shops a ARMORY SITE h Shops Armory Potomac Street Dwelling St. John’s High Street 6 House Church ruins WESTVIRGINIA MARYLAND Canal Presbyterian Church ruins RIVER Shenandoah Street Hog Alley 20 Trail to 23 Buildings/Exhibits 21 under restoration Virginius St. Peter’s Stone 19 Island N Bus Stop Church Steps Hamilton Street 18 22 16 Original St. 3 site of 5 4 2 13 POINT OF INTEREST 7 9 11 17 1 railroad 15 8 1 ? Footbridge to PARK BUILDING Arsenal C&O Canal Bridge 10 Square 13 HARPERS FERRY NHP 12 FORMER BUILDING SITE ? VISITOR INFORMATION PARK SHUTTLE BUS Market SH House PUBLIC RESTROOMS EN AN Paymaster’s D House APPALACHIAN TRAIL OA 14 H R IVER 0 .1 .2 THE POINT SCALE IN TENTHS OF MILES 1. INFORMATION CENTER 7. HAMILTON STREET were stored in two brick buildings here – the Start your visit here with an orientation to Building foundations and photos mark the Small Arsenal and Large Arsenal. park stories and information. sites of a pre-Civil War riverside neighborhood. 13. JOHN BROWN’S FORT 2. RESTORATION MUSEUM Originally the Armory’s fire enginehouse and Explore “layers” of history and discover how 8. HARPERS FERRY: A PLACE IN TIME watchman’s office, John Brown barricaded a building changes over time. Explore the growth of the town from past to himself here during the final moments of his present. -

November 1994, Vol. 20 No. 4

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. Vol. 20, No. 4 NOVEMBER 1994 THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL PRESIDENT'S HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. MESSAGE Incorporated 1969 under Missouri General Not-For-Profit Corporatiqn Act IRS Exemption Certificate No. 501 (C)(3)-ldentification No. 51-0187715 by Robert E. Gatten, Jr. OFFICERS ACTIVE PAST PRESIDENTS It is a great honor to be able to President Irving W. Anderson serve the foundation as president this Robert E. Gatten, Jr. Portland, Oregon year. My experience as a foundation 3507 Smoketree Drive Robert K. Doerk, Jr. Greensboro, NC 27410 Great Falls, Montww member, committee member, direc Second Vice President James R. Fazio tor, and officer over the past decade Ella Mae Howard Moscow, Idaho has been such a positive and stimu 1904 4th St. N.W. V. Strode Hinds Great Falls, MT 59404 Sioux City, Iowa lating one that I hope to be able to Secretary Arlen ,J. Large repay the foundation and its mem Barbara Kubik Washington, D.C. 1712 S . Perry Court H. Jolm Montague bers in a small way by my service Kenne\\~ck, WA 99337 Portland, Oregon this year. Treasurer Donald F. Nell As I \vrite this column on Sep H. John Montague Bozeman, Montana 2928 J\TW Verde Vista Terrace William P. Sherman tember 12, I realize that it will be at Portland, OR 97210-3356 Portland, Oregon least two months before you read it. Immediate Past President L. Ect,vin Wang Thus, the contents will not exactly Stuart E. Knapp Minneapolis, Minnesota 1317 South Black Wilbur P. -

In Parisian Salons and Boston's Back Streets: Reading Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 In Parisian Salons and Boston's Back Streets: Reading Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia" David W. Lewes College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lewes, David W., "In Parisian Salons and Boston's Back Streets: Reading Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia"" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626347. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-wgdh-hg29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN PARISIAN SALONS AND BOSTON’S BACK STREETS: READING JEFFERSON’S NOTES ON THE STATE OF VIRGINIA A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by David W. Lewes 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December 2002 Chandos M. Brown Robert ATGross TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv LIST OF TABLES v ABSTRACT vi INTRODUCTION 2 CHAPTER I. PUBLICATION HISTORY 5 CHAPTER II. RECEPTION AND RESPONSE 18 CONCLUSION 51 NOTES 54 BIBLIOGRAPHY 65 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Professor Chandos Brown for his encouragement and insights during the course of this research. -

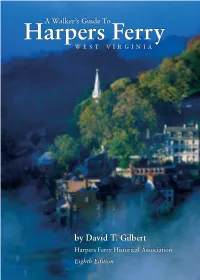

A Walker's Guide To

A Walker’s Guide To Harpers Ferry W E S T V I R G I N I A A Walker’s Guide To Harpers Ferry W E S T V I R G I N I A by David T. Gilbert Harpers Ferry Historical Association Eighth Edition Acknowledgements Table of Contents Several people have made indispensable contributions The Story of Harpers Ferry .............................. 8 to this edition of the Walker’s Guide. I am particularly indebted to Todd Bolton (Harpers Ferry NHP), David Lower Town ................................................... 25 Fox (Harpers Ferry NHP), David Guiney (Harpers Ferry Virginius Island .............................................. 73 Center, retired), Nancy Hatcher (Harpers Ferry NHP, retired), Bill Hebb (Harpers Ferry NHP, retired), Mike Storer College ............................................... 117 Jenkins (Harpers Ferry, W.Va.), Steve Lowe (Harpers Ferry NHP), Michael Murtaugh (Mercersburg, Pa.), and Maryland Heights ........................................ 131 Deborah Piscitelli (Harpers Ferry Historical Association). Loudoun Heights ......................................... 145 This guidebook would not have been possible without their generous support and assistance. Bolivar Heights ............................................ 155 Murphy Farm ............................................... 163 C&O Canal ................................................. 171 Weverton ...................................................... 183 Research Sources .......................................... 191 Index ........................................................... -

Missing Person" Incidents Since 2013

"Missing Person" Incidents Since 2013 Involvement Incident# IncidentTime ParkAlpha Summary CaseStatus On February 20, 2012 at approximately 2009hours, Supervisory Ranger Hnat received a report from dispatch in reference to overdue fisherman (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) . On February 21, 2012, Ranger Austin and I initiated a Search and Rescue to include the use of NPS fixed wing plane. Subsequently the missing persons were located by BLM fire crew, and were transported safely to Mesquite, NV. By: Missing person NP12001104 02/20/2012 20:09 MST LAKE Ranger S. Neel Closed - Found/rescued REF LM2012030142 - LAKE - ***JUVENILE SENSITIVE INFORMATION*** - Lake Mead Interagency Dispatch Center received a call from a parent stating that her juvenile son had not returned home and was possibly in the Boulder Beach Campground. Ranger Knierman and I located the individual at campsite #67 at 2341 hours. The juvenile was reunited with his Missing person NP12001373 03/04/2012 22:37 MST LAKE mother shortly thereafter. All units were clear at 0014 hours. Closed - Incident only GOLD BRANCH, LOST MALE/FOUND NO INJURIES, FORWARD, 12- Missing person; Visitor NP12001490 03/03/2012 19:30 MST CHAT 0273 Closed - Incident only Missing person; Victim NP12001537 03/09/2012 13:20 MST PORE Search, Estero Trail area, Closed - Found/rescued Page 1 of 170 "Missing Person" Incidents Since 2013 Involvement Incident# IncidentTime ParkAlpha Summary CaseStatus On March 11th 2012 at approximately 1730 hours Ranger Ruff and I were dispatched to find two people who were missing from a larger group of people near Placer Cove. Ruff and I arrived at approximately 1820 hours and found the group who contacted dispatch. -

Travels in Canada, and the United States, in 1816 and 1817 / by Lieut

Library of Congress Travels in Canada, and the United States, in 1816 and 1817 / by Lieut. Francis Hall. TRAVELS IN CANADA, AND THE UNITED STATES, IN 1816 AND 1817. BY LIEUT. FRANCIS HALL, 14TH LIGHT DRAGOONS, H. P. LONDON PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, & BROW, PATERNOSTER-ROW. 1818. LC E 165 H19 TO WILLIAM BATTIE WRIGHTSON, WILLIAM EMPSON, AND ROBERT MONSEY ROLFE, BROTHER WYKEHAMISTS, THESE TRAVELS ARE DEDICATED, BY THEIR OLD SCHOOL-FELLOW AND AFFECTIONATE FRIEND, FRANCIS HALL. TRAVELS IN CANADA, &c. &c. CHAPTER I. VOYAGE. January, 1816. I sailed from Liverpool on the 20th of January, after having been detained several weeks by a continuance of west winds, which usually prevail through the greater part of the winter. Indeed, they have become so prevalent of late years, as to approach very nearly to the nature of a trade wind. They forced us to lie to twelve, out of the forty-four days we spent on our passage. Our vessel was an American, excellently built and commanded. The American Captains are supposed, with B 2 some reason, to make quicker voyages Travels in Canada, and the United States, in 1816 and 1817 / by Lieut. Francis Hall. http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.26822 Library of Congress than the English, with whom celerity was, during the war, a less essential object. They pride themselves on the speed of their ships, as sportsmen do on that of their horses. Our Minerva was one of the first class of these “Horses of the Main.” They prefer standing across the Atlantic in the direct line of their port, to the easier but more tedious route of the trades. -

Recent Acquisitions in Americana with Material from Newly Acquired Collections on American Presidents, Early American Religion & American Artists

CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED NINETY-SEVEN Recent Acquisitions in Americana with Material from Newly Acquired Collections on American Presidents, Early American Religion & American Artists WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is made up entirely of new acquisitions, primarily in material re- lating to the United States, or the American Colonies, from the 18th to the 20th centuries. It is rich in material relating to the American presidency, early American religious history, and American artists (these reflecting recently purchased collec- tions). Notable items include an Aitken Bible; a remarkable archive relating to the Garfield assassination; letters and association copies relating to Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and Madison; and letters from John Trumbull about his work in the U.S. Capitol. New material in Western Americana has been reserved for our next catalogue, which will be devoted to that topic. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues 290, The American Revolution 1765-1783; 291, The United States Navy; 292, 96 American Manuscripts; 294, A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part I; 295, A Tribute to Wright Howes: Part II; 296, Rare Latin Americana as well as Bulletins 24, Provenance; 25, American Broadsides; 26, American Views; 27, Images of Native Americans, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. A portion of our stock may be viewed via links at www. reeseco.com. If you would like to receive e-mail notification when catalogues and lists are uploaded, please e-mail us at [email protected] or send us a fax, specifying whether you would like to receive the notifications in lieu of or in addition to paper catalogues. -

"The Eye of Thomas Jefferson" - National Gallery of Art” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 66, folder “Exhibit - "The Eye of Thomas Jefferson" - National Gallery of Art” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 66 of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON August 15, 1975 MEMORANDUM TO: TED MARRS JIM CANNON JIM CONNOR BOB GOLDWIN I RUSS ROURKE WARREN RUSTAND PAUL THEIS FROM: Carter Brown came to see me in referenc o the proposed exhibit entitled, "The Eye of Thomas Jefferson" currently scheduled for June 1 at the National Gallery of Art. Because of the forthcoming visit about that same time of Giscard d' Estaing, he is suggesting a change in the opening of the visit to the 31st of May. He thinks it would be helpful to tie in the opening of this exhibit with the visit of the President of France, who will be here at that time to present the sound and light gift to Mount Vernon. -

From the Manager in This Issue

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior HFC onMEDIA May / June | 5 Issue 7 From the Manager In This Issue Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or present are D-Day certain to miss the future. Remembered –John F. Kennedy page 2 If you are a member of the National Park Service or, for that matter, if you are a federal employee, you are affected by change. Like its colleagues in the field and program offices, Harpers Ferry Center is changing. And like change anywhere, the experience is at once New Employees exciting, and unsettling. As HFC Manager, my task is to ensure that we manage change page in a manner that ensures we meet all our commitments to the parks, that we ensure the 3 highest possible levels of both quality and accountability, and that all of us at HFC always remember that this center exists only for the purpose of serving the parks. In the coming months, you will see Harpers Ferry Center move from being a produc- Retirees er of interpretive media to becoming a facilitator of the production of interpretive media. page 4 There will be a much greater reliance on contractors and a focus on a project manage- ment approach to all our work. We will improve our communication with all parties before, during, and after projects. Never Judge page a Book by 5 its Cover If you want to make enemies, try to change something. –Woodrow Wilson Change is neither easy nor comfortable. While we will try to restrict the discomfort to within HFC, there are issues that we and the parks must work together to solve. -

Adventuresadventures WONDERFUL MEMORIES

Wild AdventuresAdventures WONDERFUL MEMORIES WEST VIRGINIA RANSON CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 216 N. Mildred St., Ranson, West Virginia 304.724.3862 • ransonwv.us Nestled in the middle of Jefferson County, Ranson is a community that doesn’t do anything halfway. Just an hour's drive from the nation's capital, our serenity and amenities burst with Blue Ridge Mountain charm. Whether you’re a roamer or a romantic, Ranson’s people, places, and historic spaces aim to please. From the exhilaration of American independence to the struggles of the Civil War, our regional history is both triumphant and tumultuous. While visiting, tread the trails of pre-Revolutionary pioneers. March in the footsteps of Civil War soldiers from Harpers Ferry to Antietam. Recall the past and relish the present. From shopping to eating, gaming to daydreaming, Ranson is a retreat from life’s routines. Experience first-hand why John Denver called the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah River "Almost Heaven." HAPPY Retreat Antietam National Battlefield Harpers Ferry Train Museum and Joy Line Railroad 301.432.5124 – 5831 Dunker Church Rd., Sharpsburg, MD – nps.gov 304.535.2521- Bakerton Rd., Harpers Ferry The bloodiest one-day battle in American history left 23,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or Admire a large collection of old toy trains and railroad memorabilia. The museum is open on missing after 12 hours of brutal combat. Explore the museum and battlefield, attend a talk, Saturdays and Sundays from 9:30 a.m. - 4 p.m. from mid-April to October. Children can take or take a self-guided hike through Civil War history. -

Unit 25 of a the B Revised

Table of Contents and Sample Unit from America the Beautiful Part 2 Part of the America the Beautiful Curriculum Copyright © 2011 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. To order your copy visit www.notgrass.com or call 1-800-211-8793. America the Beautiful Part 2: America from the Late 1800s to the Present by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-010-7 Copyright © 2011 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. Published in the United States by Notgrass Company. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations taken from the New American Standard Bible, Copyright 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation Used by permission. Lesson and Family Activities by Bethany Poore Cover design by Mary Evelyn McCurdy Interior design by Charlene Notgrass Notgrass Company 370 S. Lowe Avenue, Suite A PMB 211 Cookeville, Tennessee 38501 1-800-211-8793 www.notgrass.com [email protected] Table of Contents Part 2 Unit 16: Go West!........................................................................................................................439 Lesson 76 – Our American Story: Reformers in the White House: Hayes, Garfield, and Arthur........................................................................................440