Jrl Rafapa: an Exploration of His Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 »

REGLEMENT Jeu « Sony Days 2018 » Article 1. - Sociétés Organisatrices Sony Interactive Entertainment ® France SAS, au capital de 40 000 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le N° 399 930 593, située 92 avenue de Wagram, 75017 Paris ; Sony Mobile Communications, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre sous le n°439 961 905, située 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux ; Sony Pictures Home Entertainment France SNC, au capital de 107 500 €, enregistrée au RCS de Nanterre en date du 02/03/1987 sous le N° 324 834 266, située 25 quai Gallieni, 92150 Suresnes ; Sony Music Entertainment, France, SAS au capital de 2.524.720 €, enregistrée au RCS de Paris sous le n°542 055 603, située 52/54, rue de Châteaudun, 75009 Paris ; SONY France , succursale de Sony Europe Limited, 49-51 quai de Dion Bouton 92800 Puteaux , RCS Nanterre 390 711 323 (ci-après les « Sociétés Organisatrices ») ; organise un jeu avec obligation d’achat uniquement dans les magasins Fnac et Darty ainsi que sur le sites www.fnac.com et www.darty.com (ci-après le « Jeu ») par le biais d’instants gagnants ouverts du 02/04/2018 10h au 15/04/2018 23h59 inclus ouvert aux personnes physiques majeures (sous réserve des dispositions indiquées à l’article 2) résidant en France Métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus). Article 2. - Participation Ce jeu est ouvert à toute personne physique majeure, résidant en France métropolitaine (Corse et DROM-COM exclus), à l'exception des mineurs, du personnel de la société organisatrice et des membres des sociétés partenaires de l'opération ainsi que de leur famille en ligne directe. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Michael Kiwanuka

Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers 9 maart 2012 nr. 285 No Risk Disc: Michael Kiwanuka www.platomania.nl • www.sounds-venlo.nl • www.kroese-online.nl • www.velvetmusic.nl N RISK Mania 285 2 VOOR 15,- € 8,50 per stuK UG DISCNIET GOED GELD TER Amadou & Mariam – Best Of Black Keys – Attack & Release Black Keys - Magic Potion Blaudzun - Seadrift Solomon Burke & De Dijk – First Aid Kit - The Big Black And MiCHaeL KiWanuKa Soundmachine Hold On Tight The Blue Home again (Polydor/Universal) Het is zeer eenvoudig vast te stellen dat Michael Kiwanuka’s ster razendsnel stijgende is. Vooral in thuisland Engeland is de 24-jarige, singer- songwriter van Oegandese afkomst nog voor zijn debuutalbum is verschenen bijzonder succesvol; hij won zo’n beetje alle debutantenprijzen. Ook op het Europese continent begint Kiwanuka’s naam Kyteman – The Hermit Sessions Daniel Lohues – Hout Moet Erwin Nyhoff – Take Your Time rond te zingen. De single Home Again was al prominent aanwezig in De Wereld Draait Door en staat bovendien op nummer 1 in België. Is het, nu de debuut-cd Home Again zo’n beetje in de winkel ligt, al deze commotie waard? Ja, zeker. In feite is dit rijk geproduceerde en sterk ouderwetse soul- album zó sterk dat de single Home Again nog wel samenvloeien in een warme sound. De soul, blues en het minst sterke liedje lijkt. De kracht zit hem niet folk van zangers als Bill Withers, Donny Hathaway en alleen in Kiwanuka’s op klassieke jaren zeventig soul Terry Callier dringt diep door in schitterende pareltjes 3 Doors Down – Away From Rufus Wainwright – Amy Winehouse - Frank leest geschoeide liedjes en diens warme stemgeluid, als Tell Me A Tale, Any Day Will Do Fine, de Otis The Sun Milwaukee At Last! maar ook vooral in de geweldige arrangementen Redding-ballad Rest en de imposante afsluiter Worry die strijkers, houtblazers en dwarsfluiten laten Walks Beside. -

Artist / Bandnavn Album Tittel Utg.År Label/ Katal.Nr

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP KOMMENTAR A 80-talls synthpop/new wave. Fikk flere hitsingler fra denne skiva, bl.a The look of ABC THE LEXICON OF LOVE 1983 VERTIGO 6359 099 GER LP love, Tears are not enough, All of my heart. Mick fra den første utgaven av Jethro Tull og Blodwyn Pig med sitt soloalbum fra ABRAHAMS, MICK MICK ABRAHAMS 1971 A&M RECORDS SP 4312 USA LP 1971. Drivende god blues / prog rock. Min første og eneste skive med det tyske heavy metal bandet. Et absolutt godt ACCEPT RESTLESS AND WILD 1982 BRAIN 0060.513 GER LP album, med Udo Dirkschneider på hylende vokal. Fikk opplevd Udo og sitt band live på Byscenen i Trondheim november 2017. Meget overraskende og positiv opplevelse, med knallsterke gitarister, og sønnen til Udo på trommer. AC/DC HIGH VOLTAGE 1975 ATL 50257 GER LP Debuten til hardrocker'ne fra Down Under. AC/DC POWERAGE 1978 ATL 50483 GER LP 6.albumet i rekken av mange utgivelser. ACKLES, DAVID AMERICAN GOTHIC 1972 EKS-75032 USA LP Strålende låtskriver, albumet produsert av Bernie Taupin, kompisen til Elton John. HEADLINES AND DEADLINES – THE HITS WARNER BROS. A-HA 1991 EUR LP OF A-HA RECORDS 7599-26773-1 Samlealbum fra de norske gutta, med låter fra perioden 1985-1991 AKKERMAN, JAN PROFILE 1972 HARVEST SHSP 4026 UK LP Soloalbum fra den glimrende gitaristen fra nederlandske progbandet Focus. Akkermann med klassisk gitar, lutt og et stor orkester til hjelp. I tillegg rockere som AKKERMAN, JAN TABERNAKEL 1973 ATCO SD 7032 USA LP Tim Bogert bass og Carmine Appice trommer. -

Jersey Beat 52

issue 52 Fall/Winter 1994 Two Dollars The Figgs. jeancuy BOUNCING SOULS Ss ‘\ MADBALL ~ EX-VEGAS NG adv The Grip Weeds ‘house of Vibes 12 song cop “Mighty trunks of rhythm, lofty lyrical leaves into gleaming orange sunshine... The Grip Weeds ROCK and this is freaking incredible. k#***” - Music PAPER, NYC. “The mighty Grip Weeds have returned, remodeled and retooled for long lasting rock and roll goodness. The Grip Weeds have acquired guitar-mistress extra- ordinaire Kristin Pinell, and toughened their sound somewhat...Recorded at the famed House of Vibes...as rock solid (if not more) than anything in the previous Grip Weeds catalog... # AAA” - THE EVIL EYE, NJ “Poised for bigger things. They've gone from being a solid genre band in the Flamin’ Groovies mold to being...well, not that much different, actually. But there's more variety, more muscle, more personality this time around. If the Goo Goo Dolls can do it, so can they.” - SOUND VIEWS, NYC BV ACE A BSE NO Ww With two seven-inch records under their belts, the Grip Weeds (New Brunswick, NJ) have now released their first full-length record. Songs full of mindblow- ing riffs, head spinning harmonies, ripping guitar ioe plas full color artwork. At a eae store near you, or send $12 plus $3 postage & handling ($5 overseas) to Ground Up Records. Major credit card holders may order by phone: g800.641.8995 TRY BEFORE YOU BUY: Download the song “Salad Days” from the [UMA (Internet Underground Music Archive). Reach IUMA via the World Wide Web at: “heep:\\sunsite.unc.edu\ianc\index. -

Order Form Full

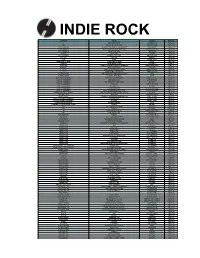

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I. -

Punk Aesthetics in Independent "New Folk", 1990-2008

PUNK AESTHETICS IN INDEPENDENT "NEW FOLK", 1990-2008 John Encarnacao Student No. 10388041 Master of Arts in Humanities and Social Sciences University of Technology, Sydney 2009 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Tony Mitchell for his suggestions for reading towards this thesis (particularly for pointing me towards Webb) and for his reading of, and feedback on, various drafts and nascent versions presented at conferences. Collin Chua was also very helpful during a period when Tony was on leave; thank you, Collin. Tony Mitchell and Kim Poole read the final draft of the thesis and provided some valuable and timely feedback. Cheers. Ian Collinson, Michelle Phillipov and Diana Springford each recommended readings; Zac Dadic sent some hard to find recordings to me from interstate; Andrew Khedoori offered me a show at 2SER-FM, where I learnt about some of the artists in this study, and where I had the good fortune to interview Dawn McCarthy; and Brendan Smyly and Diana Blom are valued colleagues of mine at University of Western Sydney who have consistently been up for robust discussions of research matters. Many thanks to you all. My friend Stephen Creswell’s amazing record collection has been readily available to me and has proved an invaluable resource. A hearty thanks! And most significant has been the support of my partner Zoë. Thanks and love to you for the many ways you helped to create a space where this research might take place. John Encarnacao 18 March 2009 iii Table of Contents Abstract vi I: Introduction 1 Frames -

Artist Album Type Apartments, the Drift Flac Apartments, the the Evening

Artist Album type Apartments, The Drift flac Apartments, The The Evening Visits...And Stays For Years flac Bats, The Couchmaster flac Bats, The Spill the Beans flac Bruce Cockburn Nothing But A Burning Light flac Chills, The Soft Bomb flac Cowboy Junkies The Trinity Session flac Fatal Mambo Fatal mambo flac Fran‡oise Hardy Clair-Obscur flac Jackson Browne Late For The Sky (Gold Disc) flac John Greaves Songs flac Jude No One Is Really Beautiful flac La's, The The La's flac Luna Bewitched flac Make Up, The I Want Some flac Mars Volta, The Frances The Mute flac Milton Nascimento Milagre Dos Peixes flac Neil Young And Crazy Horse Rust Never Sleeps flac Papas Fritas Buildings and Grounds flac Radio Tarifa Rumba Argelina flac Reverend Horton Heat, The The Full-Custom Gospel Sounds of flac Rita Mitsouko, Les The No Comprendo flac Robert Wyatt Cuckooland flac Shins, The Chutes Too Narrow flac Spain The Blue Moods of Spain flac Stone Roses, The Second Coming flac Stone Roses, The The Stone Roses flac Talk Talk Laughing Stock flac Wilco a ghost is born flac !!! Louden Up Now flac Air Miami me. me. me flac Al Stewart Year Of The Cat flac Alain Bashung Climax - Disc 1 flac Alain Bashung Climax - Disc 2 flac America History- America's Greatest Hits flac Apartments, The Apart flac Apartments, The Fete Foraine flac Arctic Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm flacNot Arno Charlatan mp3 Barbara L'aigle noir flac Barclay James Harvest Gone To Earth flac Ben Lee Grandpaw Would flac Beta Band, The The Beta Band flac Cesaria Evora L'essentiel flac Citizen Cope The Clarence Greenwood Recordings flac Day One Ordinary Man flac Decemberists, The Picaresque flac Donald Fagen The Nightfly flac Dr.