(Rhinocheilus Lecontei), a `Specialist' Predator?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

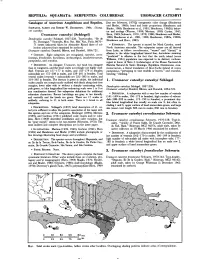

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Lake Pinaroo Ramsar Site

Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site Disclaimer The Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW (DECC) has compiled the Ecological character description: Lake Pinaroo Ramsar site in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECC does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. © State of New South Wales and Department of Environment and Climate Change DECC is pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney PO Box A290, Sydney South 1232 Phone: 131555 (NSW only – publications and information requests) (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/275 ISBN 978 1 74122 839 7 June 2008 Printed on environmentally sustainable paper Cover photos Inset upper: Lake Pinaroo in flood, 1976 (DECC) Aerial: Lake Pinaroo in flood, March 1976 (DECC) Inset lower left: Blue-billed duck (R. Kingsford) Inset lower middle: Red-necked avocet (C. Herbert) Inset lower right: Red-capped plover (C. Herbert) Summary An ecological character description has been defined as ‘the combination of the ecosystem components, processes, benefits and services that characterise a wetland at a given point in time’. -

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Pituophis Catenifer

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer Great Basin Gophersnake – P.C. deserticola Bullsnake – P.C. sayi in Canada EXTIRPATED - Pacific Northwestern Gophersnake – P.c. catenifer THREATENED - Great Basin Gophersnake – P.c. deserticola DATA DEFICIENT - Bullsnake – P.c. sayi 2002 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION DES ENDANGERED WILDLIFE IN ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC 2002. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 33 pp. Waye, H., and C. Shewchuk. 2002. COSEWIC status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Gophersnake Pituophis catenifer in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-33 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation de la couleuvre à nez mince (Pituophis catenifer) au Canada Cover illustration: Gophersnake — Illustration by Sarah Ingwersen, Aurora, Ontario. -

Identifying Amphibians and Reptiles in Zoos and Aquariums ZOO VIEW

290 ZOO VIEW Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(2), 290–294. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Identifying Amphibians and Reptiles in Zoos and Aquariums PLUS ҫa ChanGe, PluS C’eST la même ChoSe [The more ThinGS ChanGe, Snakes and their allies were traditionally placed in the genus THE MORE THEY STAY THE SAME] Elaphe but were recently referred to Pantherophis based on their —JEAN-BAPTISTE ALPHONSE KARR, 1849 close relationship to other lampropeltine colubrids of the New World (Burbrink and Lawson 2007). Different combinations are Reptiles and amphibians are relatively unique in the sense used by different authors and my colleagues are struggling with of constantly changing taxonomies. That phenomenon simply is these differences; in other words, which names should they use? not a big operative problem for bird and mammal zoo person- Some biologists believe that there is a rule that the most recent nel. To gain a sense of why this is happening, refer to Frost and taxonomic paper should be the one used but there is no such Hillis (1990). There is confusion caused by changes in both stan- established convention in the Code (The International Code of dard and scientific names in herpetology. The general principle Zoological Nomenclature). Recently, a convincing description of in a zoo is that one wants to be talking about the same species the dangers of taxonomic vandalism leading to potential desta- when putting live animals together for breeding or exhibit or bilization has appeared in the literature (Kaiser et al. 2013) and analyzing records for genealogy or research. -

Activity Budget and Spatial Behavior of the Emerald Tree Boa Corallus Batesii

Activity Budget and Spatial Behavior of the Emerald Tree Boa Corallus batesii Faculty Member #1 Joseph R. Mendelson III Signature Faculty Member #2 Emily G. Weigel Signature 2 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my primary research advisor, Professor Joseph Mendelson, for your guidance and support. Thank you for inviting me to be a part of the emerald boa project and for investing so much time in helping me to become a scientist. I would also like to thank my second research advisor, Professor Emily Weigel, for helping me to get involved in research. Thank you for all of your help with my statistics and analysis and for providing detailed feedback to help me improve my scientific writing. Next, I would like to thank members of my research team: Liz Haseltine, Sav Berry, and Ellen Sproule. Thank you for organizing this study and for your help analyzing our 1,104 hours of video footage. I would like to thank members of the Spatial Ecology and Paleontology lab for your help in training me to become a better researcher. Thank you to Professor Jenny McGuire, Dr. Sílvia Pineda-Munoz, Dr. Yue Wang, Dr. Rachel Short, and Julia Schap. A special thanks to Ben Shipley and Danny Lauer for teaching me how to use R. Finally, I would like to thank my family for your continuous support while I study to become a wildlife biologist. Thank you for listening to me talk about snakes for the past few years. 3 Abstract Corallus batesii is a boid snake native to the Amazon basin. -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

De Los Reptiles Del Yasuní

guía dinámica de los reptiles del yasuní omar torres coordinador editorial Lista de especies Número de especies: 113 Amphisbaenia Amphisbaenidae Amphisbaena bassleri, Culebras ciegas Squamata: Serpentes Boidae Boa constrictor, Boas matacaballo Corallus hortulanus, Boas de los jardines Epicrates cenchria, Boas arcoiris Eunectes murinus, Anacondas Colubridae: Dipsadinae Atractus major, Culebras tierreras cafés Atractus collaris, Culebras tierreras de collares Atractus elaps, Falsas corales tierreras Atractus occipitoalbus, Culebras tierreras grises Atractus snethlageae, Culebras tierreras Clelia clelia, Chontas Dipsas catesbyi, Culebras caracoleras de Catesby Dipsas indica, Culebras caracoleras neotropicales Drepanoides anomalus, Culebras hoz Erythrolamprus reginae, Culebras terrestres reales Erythrolamprus typhlus, Culebras terrestres ciegas Erythrolamprus guentheri, Falsas corales de nuca rosa Helicops angulatus, Culebras de agua anguladas Helicops pastazae, Culebras de agua de Pastaza Helicops leopardinus, Culebras de agua leopardo Helicops petersi, Culebras de agua de Peters Hydrops triangularis, Culebras de agua triángulo Hydrops martii, Culebras de agua amazónicas Imantodes lentiferus, Cordoncillos del Amazonas Imantodes cenchoa, Cordoncillos comunes Leptodeira annulata, Serpientes ojos de gato anilladas Oxyrhopus petolarius, Falsas corales amazónicas Oxyrhopus melanogenys, Falsas corales oscuras Oxyrhopus vanidicus, Falsas corales Philodryas argentea, Serpientes liana verdes de banda plateada Philodryas viridissima, Serpientes corredoras -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Species Selection Process

FINAL Appendix J to S Volume 3, Book 2 JULY 2008 COYOTE SPRINGS INVESTMENT PLANNED DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FINAL VOLUME 3 Coyote Springs Investment Planned Development Project Appendix J to S July 2008 Prepared EIS for: LEAD AGENCY U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Reno, NV COOPERATING AGENCIES U.S. Army Corps of Engineers St. George, UT U.S. Bureau of Land Management Ely, NV Prepared MSHCP for: Coyote Springs Investment LLC 6600 North Wingfield Parkway Sparks, NV 89496 Prepared by: ENTRIX, Inc. 2300 Clayton Road, Suite 200 Concord, CA 94520 Huffman-Broadway Group 828 Mission Avenue San Rafael, CA 94901 Resource Concepts, Inc. 340 North Minnesota Street Carson City, NV 89703 PROJECT NO. 3132201 COYOTE SPRINGS INVESTMENT PLANNED DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Appendix J to S ENTRIX, Inc. Huffman-Broadway Group Resource Concepts, Inc. 2300 Clayton Road, Suite 200 828 Mission Avenue 340 North Minnesota Street Concord, CA 94520 San Rafael, CA 94901 Carson City, NV 89703 Phone 925.935.9920 Fax 925.935.5368 Phone 415.925.2000 Fax 415.925.2006 Phone 775.883.1600 Fax 775.883.1656 LIST OF APPENDICES Appendix J Mitigation Plan, The Coyote Springs Development Project, Lincoln County, Nevada Appendix K Summary of Nevada Water Law and its Administration Appendix L Alternate Sites and Scenarios Appendix M Section 106 and Tribal Consultation Documents Appendix N Fiscal Impact Analysis Appendix O Executive Summary of Master Traffic Study for Clark County Development Appendix P Applicant for Clean Water Act Section 404 Permit Application, Coyote Springs Project, Lincoln County, Nevada Appendix Q Response to Comments on the Draft EIS Appendix R Agreement for Settlement of all Claims to Groundwater in the Coyote Spring Basin Appendix S Species Selection Process JULY 2008 FINAL i APPENDIX S Species Selection Process Table of Contents Appendix S: Species Selection Process ........................................................................................................ -

(I) Sections 10-16

APPENDIX 1 FLORA DETAILS Appendix 1: Flora Details Table 1.1: Flora species observed on the subject site by Keystone Ecological for this study. Cover abundance ratings (see text for details) are provided for full floristic quadrats (Q1 to Q7), each of 400 m2. Species observed nearby those quadrats within the same vegetation type are shown as ‘N’. Species observed in other parts of the site during random meander (RM) are indicated by ‘x’,. Additional species not found during survey but reported by Mark Fitzgerald (2005) are indicated (x), but their locations are not known and may not have been observed on site. Vegetation type and quadrat Family Scientific Name Common Name 2/3 1 2 1 2 2 RM MF Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Acanthaceae Thunbergia alata* Black-eyed Susan N Amaranthaceae Deeringia amaranthoides - 2 Anacardiaceae Euroschinus falcatus var. falcatus Ribbonwood x Apocynaceae Parsonsia straminea Common Silkpod 2 2 1 Araliaceae Polyscias elegans Black Pencil Cedar 2 2 2 4b Araliaceae Schefflera actinophylla* Umbrella Tree 2 4b 2 N Arecaceae Archontophoenix cunninghamiana Bangalow Palm 1 3 Arecaceae Livistona australis Cabbage Tree Palm 2 1 Arecaceae Syagrus romanzoffiana* Cocos Palm N Asparagaceae Asparagus aethiopicus* Asparagus Fern 4b 4b 3 1 1 N Asparagaceae Asparagus densiflorus* Asparagus Fern 4b 4b Aspleniaceae Asplenium australasicum Birds Nest Fern N 1 N Asteliaceae Cordyline stricta Narrow-leaf Palm Lily 1 Asteraceae Conyza sp.* - 1 Asteraceae Delairea odorata* Cape Ivy N Bignoniaceae Pandorea pandorana Wonga Vine N 2 1 Casuarinaceae -

Boidae, Boinae): a Rare Snake from the Vale Do Ribeira, State of São Paulo, Brazil

SALAMANDRA 47(2) 112–115 20 May 2011 ISSNCorrespondence 0036–3375 Correspondence New record of Corallus cropanii (Boidae, Boinae): a rare snake from the Vale do Ribeira, State of São Paulo, Brazil Paulo R. Machado-Filho 1, Marcelo R. Duarte 1, Leandro F. do Carmo 2 & Francisco L. Franco 1 1) Laboratório de Herpetologia, Instituto Butantan, Av. Vital Brazil, 1500, São Paulo, SP, CEP: 05503-900, Brazil 2) Departamento de Agroindústria, Alimentos e Nutrição. Escola Superior de Agronomia “Luiz de Queiroz” – ESALQ/USP, Av. Pádua Dias, 11 C.P.: 9, Piracicaba, SP, CEP: 13418-900, Brazil Correspondig author: Francisco L. Franco, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 9 December 2010 The boid genusCorallus Daudin, 1803 is comprised of nine Until recently, only four specimens (including the above Neotropical species (Henderson et al. 2009): Corallus an mentioned holotype) of C. cropanii were deposited in her- nulatus (Cope, 1876), Corallus batesii (Gray, 1860), Co petological collections: three in the Coleção Herpetológica rallus blombergi (Rendahl & Vestergren, 1941), Coral “Alphonse Richard Hoge”, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, lus caninus (Linnaeus, 1758), Corallus cookii Gray, 1842, Corallus cropanii (Hoge, 1954), Corallus grenadensis (Bar- bour, 1914), Corallus hortulanus (Linnaeus, 1758), and Corallus ruschenbergerii (Cope, 1876). The most conspic- uous morphological attributes of representatives of these species are the laterally compressed body, robust head, slim neck, and the presence of deep pits in some of the la- bial scales (Henderson 1993a, 1997). Species of Corallus are distributed from northern Central American to south- ern Brazil, including Trinidad and Tobago and islands of the south Caribbean. Four species occur in Brazil: Corallus batesii, C.