Sensemaking in Organisations: a Study of News Channels in Gujarat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES /~Nglish Version)

eries, Vol. XXXII, No.1 ~onday,June13,1994 Jyaistha 23,1916 (Saka) ~ /J7r .t:... /jt.. LOK SABHA DEBATES /~nglish Version) Tenth Session (Tenth Lok Sabha) PARLIAMENT LiBRARY No................... ~, 3 ......~' -- l)ate ... _ -~.. :.g.~ ~ ..... - (Vol. XXXIJ contains No. I to 2) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price: Rs., 50,00 [ORIGINAL ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGLISH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE TREATED AS AUTHORITATIVE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF.) \.J1 (') ".... r--. 0'\ 0 .... ..... t- -.1 ::s ct ..... ....... ct" "- ~ ~ CD ~ \.0 _. ..... ::s ..... vJ e;- O' ~ ::s en Po I-cJ i ..~ &CD ~ p ~ ~ m .... c.; Cl to tp ~ p; ::r t- Il' .. r-- rt c.". ..... b' t: t=~ I'i' t- ~ Ll> .... ~ ti t- \.0 ::s t<: ~ \.0 ~ su ~ .. ~ cr. 0 ~ ..... ~ 0 .. ~ Ci; ~ )--'. 0' Ii (i..i :::T I~ CD ::r Ii ;::F '1 'Ii ~ :::T jl) cT ,-. 11 ~ tJ· I ~ 0 ()q ,.... ~ t. (I) !i. .... .- c: eD ::s (1) 112 w r) .... fl) Z ..., .1- Ql ~ -~ ..... tJ' .~ . Q ~ ~ 0 ~ 0 III SU . g;. I\) ::s '-' p:> g ~ Ii I';" .. g _" ~ 1.0.... 0'\ ,...... (l)C04 CI b:I ttl (/2 PlSl'l ::r .... PI ~ :::r c.". I-' ~ tS' ~~ .g jl) .... ~ ....,~ ::S~ .., tel ~ ~! ~ ~ SU ::s U; ~(I) .. ::r (j) Ii &~ ::r t- ti .... f-Io :?: § .~ ,.... ~ CQ . ::r ~ ::s ;S; ~ ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERRS TENTH LOK SABHA A Ayub Khan, Shri (Jhunjhunu) Abdul Ghafoor, Shr; (Gopalganj) Azam, Dr. Faiyazul (Bettiah) oedya Nath, Mahant (Gorakhpur) B Ar"aria, Shri Basudeb (Bankura) Baitha, Shri Mahendra (Bagaha) Adaikalaraj, Shri L. (TiruchirapaUi) Bala, Dr. Asim (Nabadwip) Advani, Shri Lal K. -

Answered On:19.12.2001 Pm`S Foreign Trips Priya Ranjan Dasmunsi;Uttamrao Deorao Patil

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA EXTERNAL AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:4446 ANSWERED ON:19.12.2001 PM`S FOREIGN TRIPS PRIYA RANJAN DASMUNSI;UTTAMRAO DEORAO PATIL Will the Minister of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) the number of foreign trips our Prime Minister has undertaken since the inception of 13th Lok Sabha till November 15, 2001 including the date and period of stay etc.; (b) the composition of Media contingent-both print and electronic media-including the names of media personnel, electronics media, crew etc. and the names of the newspapers in each trip; (c) whether the media personnel have been looked after at Government cost or they had to pay their telephone and news transmitting charges like Fax, Telex, E-mail or Internet services; and (d) If so, the details thereof Answer THE MINISTER OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS (SHRI JASWAT SINGH) (a): The information is placed at Annexure I (b): The information is placed at Annexure II-IX (c & d): The Government does not provide for the boarding and lodging of the media delegation accompanying the Prime Minister on visits abroad. This expenditure, including any on telephone calls and faxes made from respective hotel rooms, are paid for by the media delegates themselves. To facilitate reporting from places visited, the Government arranges a media center with limited communication facilities especially computers with e-mail. Annexure I The Prime Minister had undertaken 8 (eight) trips abroad since the inception of 13th Lok Sabha till November 15, 2001. The details are as under: S.No. Countries Visited Date 1. South Africa November 11-18, 1999 2. -

Annexure-Iii

ANNEXURE-III LIST OF PUBLICATION UNITS TO WHOM QUESTIONAIRE WAS SENT SL.NO. NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE CODE LANGUAGE CIRCULATION 1 Pledge Hyderabad 100076 ENG 50463 2 Hindi Milap Hyderabad 120304 HIN 31167 3 Siyasat Hyderabad 160006 URD 42744 4 Andhra Jyothi Hyderabad 410093 TEL 33281 5 Andhra Prabha Hyderabad 410014 TEL 25000 6 Prajashakti Hyderabad 410173 TEL 11387 7 Tel.J.D.Patrika Vaartha Hyderabad 410151 TEL 101241 8 Ushodayam S.Dina.Patrika Hyderabad 410148 TEL 30719 9 Andhra Prabha Karimnagar 410207 TEL 25000 10 Deccan Chronicle Secunderabad 100447 ENG 222849 11 Andhra Bhoomi Secunderabad 410119 TEL 8258 12 Neti Manadesam Vijayawada 410214 TEL 25000 13 Vijayabhanu Visakhapatnam 410007 TEL 65256 14 Visakha Samachram Visakhapatnam 410123 TEL 55500 15 Assam Tribune Guwahati 100050 ENG 58547 16 North East Times Guwahati 100442 ENG 8418 17 Sentinel Guwahati 100074 ENG 44483 18 Purvanchal Prahari Guwahati 122350 HIN 14679 19 AJI Guwahati 300074 ASS 54466 20 Ajir-Asom Guwahati 300036 ASS 11160 21 Amar Asom Guwahati 300071 ASS 46916 22 Asomiya Khabar Guwahati 300078 ASS 46999 23 Asomiya Pratidin Guwahati 300068 ASS 59910 24 Dainik Agradoot Guwahati 300069 ASS 25000 25 Dainik Asam Guwahati 300001 ASS 12376 26 Jugasankha Guwahati 310558 BEN 82681 27 Dainik Sonar Cachar Silchar 310005 BEN 25000 28 The Hindustan Times Patna 100215 ENG 25000 29 Qaumi Tanzeem Patna 160014 URD 46842 30 Sangam Patna 100010 URD 47091 31 The Asian Age Ahmedabad 100719 ENG 22936 32 Alp Viram Ahmedabad 123493 HIN 76843 33 Gujarat Vaibhav Ahmedabad 123908 HIN 231315 -

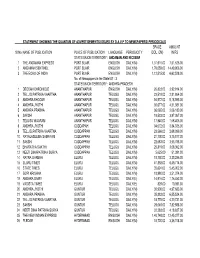

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00 -

Annual Report 2016-17 CORPORATE INFORMATION

Annual Report 2016-17 CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Mr. Kiran B Vadodaria Chairman & Managing Director Mr. Manoj B Vadodaria Non-Executive Director Mr. Amit Kumar Ray Whole-Time Director Mr. N R Mehta Independent Director Mr. Dilip D Patel Independent Director Mr. Om Prakash Bhandari Independent Director Ms. Seema G Saxena Independent Director CHIEF FINANCE OFFICER: Mr. Kalpesh R Pandya COMPANY SECRETARY : BANKERS: Ms. Palak P Asawa DENA BANK AUDITORS: SECRETARIAL AUDITOR: M/s. Dhirubhai Shah & Doshi M/s. Umesh Ved & Associates Chartered Accountants, Practicing Company Secretaries, Ahmedabad Ahmedabad REGISTERED OFFICE AND CONTACT DETAILS: M UMBAI OFFICE: “Sambhaav House”, Opp. Judges’ Bungalows 417, Hind Rajasthan Building, Premchandnagar Road Dada Saheb Phalke Road, Satellite, Ahmedabad - 380 015 [Gujarat] Near Dadar Station, Tel No. +91 79 2687 3914/15/16/17 Dadar (East), Fax No. +91 79 2687 3922 Mumbai - 400 014 [Maharashtra] Website: www.sambhaavnews.com Email: [email protected] CORPORATE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER: CIN: L67120GJ1990PLC014094 REGISTRAR & SHARE TRANSFER AGENT: MCS Share Transfer Agent Limited 201, Shatdal Complex, Third Floor, Opp. Bata Show Room, Ashram Road, Ahmedabad - 380 009 [Gujarat] Tel No. +91 79 2658 0461/62/63 Fax No. +91 79 2658 1296 Website: www.mcsregistrars.com Email: [email protected] SAMBHAAV MEDIA LIMITED NOTICE NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT THE 27TH ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE MEMBERS OF SAMBHAAV MEDIA LIMITED WILL BE HELD ON FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29,2017 AT 10:30 A.M. AT THE REGISTERED OFFICE OF THE COMPANY SITUATED AT “SAMBHAAV HOUSE”, OPP. JUDGES’ BUNGALOWS, PREMCHANDNAGAR ROAD, SATELLITE, AHMEDABAD - 380 015 TO TRANSACT THE FOLLOWING BUSINESS: ORDINARY BUSINESS: 1. -

Kevalkumar M. Patel1 and Avinashi Mahant2

e-Library Science Research Journal ISSN : 2319-8435 Impact Factor : 2.2030(UIF) Vol.3 | Issue.4 | Feb. 2015 Available online at www.lsrj.in A BIBLIOMETRIC STUDY OF INDIA PRESS: FREE ONLINE E- NEWSPAPERS Kevalkumar M. Patel1 and Avinashi Mahant2 1Librarian of C. K. Shah Vijapurwala Institute of Management, Pratapnagar, Vadodara, Gujarat. 2Librarian of Anand People’s Medicare Society, Anand, Gujarat. Abstract:-The “India Press” (http://www.indiapress.org) provides read free online newspapers links to all Indian different language daily newspapers without downloading their fonts including all regional newspapers of India. In this research paper author made an effect to study the total number of 101 full texts read free online newspapers were accesses through “India Press” and analyzed based on title/alphabetical word wise, state wise, languages wise published in India their accessibility of archives of read free online newspapers. Keywords:Online Newspapers, Read Free Online Open Access, Online E-Newspapers, India Press 1.INTRODUCTION A newspaper plays an important role in disseminating current information and events and keeps its readers up-to-date. The electronic newspaper or e-newspaper is a self-contained, reusable and refreshable version of a traditional newspaper that acquires and holds information electronically. Moreover, electronic newspapers retrieve information electronically from online databases, process it electronically with word processors, desktop publishing packages and a variety of more technical hardware and software, and transmit it electronically to the end- users. Broadly speaking, e-news items which evolve from ‘online newspaper’, ‘PDF newspaper’, and ‘e-news via e- devices’ may not be taken synonymously since they are different from each other in terms of developments and use. -

Rating Rationale Sambhaav Media Ltd. 19 Mar 2021 Brickwork Ratings

Rating Rationale Sambhaav Media Ltd. 19 Mar 2021 Brickwork Ratings reaffirms the ratings for the enhanced Bank Loan Facilities of ₹. 29.09 Crores of Sambhaav Media Ltd. (‘SML’ or the ‘Company’) Particulars Amount (₹ Crs) Rating* Facility Tenure Previous Previous Present Present (27Dec2019) BWR BBB- BWR BBB- Fund Based 14.28 19.01 Long Term Stable Stable Non-fund Based 5.00 10.08 Short Term BWR A3 BWR A3 Total 154.22 29.09 ₹ Twenty Nine Crores and Nine Lakhs Only *Please refer to BWR website www.brickworkratings.com/ for definition of the ratings Details of Bank facilities are provided in Annexure-I Brickwork Ratings has reaffirmed 'BWR BBB-/Stable/A3' rating for the enhanced bank facilities of Sambhaav Media Ltd. RATING ACTION / OUTLOOK The ratings continue to draw strength from its operational track record, strong regional market presence , diversified revenue stream, experienced management having healthy relationships with customers and its comfortable financial risk profile. However, the ratings continue to be constrained by the moderate scale of operations, its significant dependence on advertisement revenue and exposure to competition in the industry. Brickwork Ratings has considered the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the measures taken by the Company to mitigate the impact. The pandemic has majorly affected the company’s scale of operations and cashflows. The lockdown situation and muted economic activity have led to significant drop in advertising revenue. Operating performance was impacted during Q1FY21 owing to Covid19 pandemic and the resultant disruptions in operations. SML reported revenue of Rs. 6.70 Crs in Q1FY21 against revenue of Rs. -

Report on the Reconstruction of the Process of Civil Society Consultation for the Approach to the 12Th Five Year Plan

Report On The Reconstruction of the Process of Civil Society Consultation for the Approach to the 12th Five Year Plan Voluntary Action Cell Planning Commission Government of India New Delhi April, 2015 Contents Item Page No. 1. Highlights 1-3 2. Background 4-7 3. The Worlds of the Voluntary Sector 8-10 4. The CS-Consultation Process 11-17 5. Way Forward 18 6. Annexures I. List of Officials/Non-Officials of Planning Commission and 19 External stakeholders consulted for reconstructing the process of CS-Consultation II. Process chart on CS-Consultations/ engagement in 12th Five 20-21 Year Plan III. Chronology of events 22-23 IV. List of CSOs and civil society representatives participated in 24-67 the CS-Consultations anchored by WNTA 1. Highlights 1. An extensive Civil Society-Consultation (CSC) to provide inputs for the Approach Paper to the 12th FY Plan was held involving large number of CSOs, as highlighted in the Approach Paper as well as in the 12th FY Plan Document. 2. Voluntary Action Cell has held extensive discussions with those who were reportedly actively involved in the process, namely, two Members of the Planning Commission; Principal Adviser, a couple of Advisers and a few other officials of the Planning Commission; Chairperson, Statistical Commission of India & the then Principal Adviser (PCMD), Planning Commission and also with some key ‘external’ stakeholders. 3. This report is an attempt to reconstruct the entire CSC process that was held under the aegis of the erstwhile Planning Commission as record for reference if any in future. The Report has been prepared After consulting several ‘external’ and ‘internal’ stakeholders who were involved in the “Civil Society (CS) - Consultation Process”. -

Section 25 Companies

Note:The information contained in the list is derived from e-records available in the MCA portal. If any discrepancy/ deviation is noticed by company/ representative of company, the same may be kindly brought to the notice of ministry for rectification. LIST OF SECTION25 COMPANIES S.No CIN COMPANY NAME REG DATE COMPANY ADDRESS 1 U80100AP1992NPL014292 NAGARJUNA FOUNDATION 5/27/1992 NAGARJUNA HILLS,PANJAGUTTA,HYDERABAD HYDERABAD HYDERABAD Andhra 2 U92140AP1993NPL015662 AUROBHARATHI DEVELOPMENT 4/20/1993 GADDIPLLI [PO], GAREDIPALLI[M]NALGONDA DIST. NALGONDA Andhra Pradesh 508201 3 U80101AP1995NPL022410 K V K RAJU INTERNATIONAL LEADERSHIP 11/28/1995 NAGARJUNA HILLS, PANJAGUTTA,HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 U85110AP1997NPL027669 RAVINDRANATH MEDICAL FOUNDATION 8/4/1997 PLOT NO.303, ROAD NO.25,JUBILEE HILLS HYDERABAD HYDERABAD Andhra Pradesh 5 U24239AP1998NPL028706 VARUN HERBALS ( UNDER SECTION 25 ) 1/9/1998 5-8-293/AMAHESH NAGAR, CHIRAG ALI LANE, HYDERABAD Andhra Pradesh 500001 6 U01122AP1998NPL029019 MAGENE RESEARCH FOUNDATION 3/9/1998 PLOT NO. 144, IST FLOOR AKASHGANGA SRI NAGAR COLONY HYDERABAD ANDHRA 7 U01222AP1998NPL029027 BHARAT EGG PRODUCERS' ASSOCIATION 3/9/1998 3-5-823, II FLOOR,HYDERABAD BUSINESS CENTRE HYDERGUDA HYDERABAD - 500 029. 8 U65921AP1998NPL029996 ANDHRA PRADESH HIRE PURCHASE 8/20/1998 3-5-144/6,EDEN GARDEN HYDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH Andhra Pradesh 500001 9 U91120MH2006NPL159620 HERD EDUCATIONAL AND MEDICAL 2/8/2006 MAATOSHRI 206/3AGPO SQUARE CIVIL LINES NAGPUR Maharashtra 440001 RESEARCH FOUNDATION 10 U85310AP2002NPL039412 V-CARE FOUNDATION 8/2/2002 7, SRIDURGA CHAMBERS,THAKUR MANSION LANE, PANJAGUTTA, HYDERABAD - 500 082 11 U80102AP2003NPL040577 REGANTI ORPHAN'S EDUCATIONAL 2/26/2003 8-2-2932A,PLOT.NO.56,JUBILEEHILLS HYDERABA - 500 033 Andhra Pradesh 12 U80301AP2003NPL042195 GMR VARALAKSHMI FOUNDATION 12/9/2003 GMR NAGAR, RAJAM,SRIKAKULAM DIST-532 127. -

Annual Report 2019-20

CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS: AUDIT COMMITTEE MEMBERS: CORPORATE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER: Mr. Kiran B Vadodaria Mr. N R Mehta (Chairman) CIN: L67120GJ1990PLC014094 Chairman & Managing Director Mr. O P Bhandari (Member) DIN: 00092067 Mr. Dilip D Patel (Member) LISTED ON STOCK EXCHANGES: BSE Limited Mr. Manoj B Vadodaria NOMINATION AND REMUNERATION National Stock Exchange of India Limited Non-Executive Director COMMITTEE MEMBERS: DIN: 00092053 Mr. N R Mehta (Chairman) RESIGTRAR & SHARE TRANSFER AGENT: Mr. O P Bhandari (Member) M/s. MCS Share Transfer Agent Limited Mr. Amit Kumar Ray Whole-Time Director Mr. Dilip D Patel (Member) 201, Shatdal Complex, 2nd Floor, DIN: 06468634 Opp. Bata Show Room, Ashram Road STAKEHOLDERS’ RELATIONSHIP Ahmedabad - 380 009 [Gujarat] Mr. N R Mehta COMMITTEE: Tel No. +91 79 2658 0461/62/63, Non-Executive Independent Director Mr. N R Mehta (Chairman) Fax No. +91 79 2658 1296 DIN: 00092386 Mr. Kiran B Vadodaria (Member) Website: www.mcsregistrars.com Mr. Manoj B Vadodaria (Member) Email: [email protected] Mr. Dilip D Patel Non-Executive Independent Director STATUTORY AUDITOR: REGISTERED OFFICE: DIN: 01523277 M/s. R K Doshi & Co LLP “Sambhaav House”, Chartered Accountants Opp. Judges’ Bungalows, Mr. O P Bhandari Non-Executive Independent Director Doshi Corporate Park, Premchandnagar Road, DIN: 00056458 Nr. Utkarsh School, Satellite, Ahmedabad - 380 015 [Gujarat] Akshar Marg, Tel No. +91 79 2687 3914/15/16/17 Mrs. Gouri P Popat Rajkot - 360 001[Gujarat] Fax No. +91 79 2687 3922 Non-Executive Independent Woman Director Website: www.sambhaav.com DIN: 08356151 SECRETARIAL AUDITOR: Email: [email protected] M/s. Umesh Ved & Associates CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER: MUMBAI OFFICE: Practicing Company Secretaries Mr. -

India Media Outlets

India Media Directory India Newswire 1st Headlines A India News Aaj Tak Aajkaal Aajkal Adinor Sombad Adyar Times Afternoon Despatch and Courier Afternoon Voice Agra News Agri Watch Ahmedabad Mirror Ajir Asom Ajir Dainik Batori Ajit Akila Al Hindelyom All India News Amar Ujala Amar Ujala Ananda Bazar Patrika Ananda Vikatan Anandabazar Patrika Andaman Chronicle Andhra Bhoomi Andhra Jyothi Andhra News Andolana Anna Nagar Times Anweshanam Apna Samachar Arunachal Times Asia Times Asian Age Asomiya Pratidin Assam Live Assam Tribune Assamiya Khabor Aurangabad Times BTV IN Bangalore Mirror Bartaman Patrika Bengal Net Bharat Observer Big News Network Bihar Times Bombay News Bombay Samachar Business Line Business Standard Business Today Business World Business and Economy CNBC TV18 CNN IBN Cashmere News Central Chronicle Charhdikala Charhdikala Chennai Online Chennai Vision Chitralekha Chitralekha Chitralekha Citizen Matters Corporate India DD News DLA AM DNA Daily Aftab Daily Desher Katha Daily Thanthi Dainik Agradoot Dainik Aikya Dainik Bhaskar Dainik Bhaskar Dainik Ekmat Dainik Jagran Dainik Jagran Dainik Navajyoti Dainik Sandhya Prakash Dainik Statesman Dainik Suprovat Dalal Street Darjeeling Times Day After Deccan Chronicle Deccan Chronicle Deccan Herald Deepika Dehradun Classified Desh Videsh Times Deshabhimani Deshbandhu Deshonnati Dharitri Dinakaran Dinakaran Dinalipi Dinamalar Dinamani Dinathanthi Dinathanthi Divya Bhaskar Divya Bhaskar E Ahmadnagar E Pao Eastern Mirror Economic Times Economic Times Economic Times Economic and Political