Endangered Species Bulletin, Vol 27 No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amaranthus Pumilus (Seabeach Amaranth)

Bartonia No. 61, 2002-News and Notes Amaranthus pumilus Raf. (Seabeach Amaranth, Amaranthaceae) Rediscovered in Sussex County, Delaware In August of 2000, Amaranthus pumilus was rediscovered in Sussex Co., Delaware after 125 years without a sighting. It was first collected in Delaware in 1875 by Albert Commons (10 September 1875, A. Commons, s.n., "seabeach, Baltimore Hundred, Delaware," PH). Amaranthus pumilus was federally listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1993. Historically, this species was known from Massachusetts south to South Carolina (Weakley et al. 1996). Amaranthus pumilus was reported as rediscovered at Assateague Island National Seashore, Worcester County, Maryland in 1998 (Ramsey 2000). Prior to rediscovery on Assateague Island and in Sussex County, A. pumilus was extant on Long Island, New York, and in North Carolina and South Carolina. Lisa Marie Kendall of the Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Delaware Department of Natural Resources discovered the first plants on 7 August 2000. Subsequent surveys revealed a total of 41 individuals scattered over 22 kilometers of Atlantic shoreline. All plants found are within the boundaries of Delaware Seashore and Fenwick Island State Parks. The largest number of plants (28) was found within a 1.5-km stretch of shoreline near the swimming beach at Delaware Seashore State Park. This section of beach is the only area where A. pumilus was found that is off-limits to vehicular traffic. This area provides the best habitat for the long-term survival of A. pumilus. Individual plants were found growing on relatively open sand near the base of the primary foredune. -

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex Rotundifolia L. F. (Lamiaceae)

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex United States rotundifolia L. f. (Lamiaceae) – Beach Department of Agriculture vitex Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service June 4, 2013 Version 2 Left: Infestation in South Carolina growing down to water line and with runners and fruit stripped by major winter storm (Randy Westbrooks, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org). Right: A runner with flowering shoots (Forest and Kim Starr, Starr Environmental, Bugwood.org). Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex rotundifolia Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is defined as “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA)—specifically, the PPQ WRA model (Koop et al., 2012)—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because the PPQ WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or for any area within it. -

Vitex Rotundifolia L.F

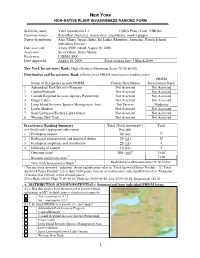

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Vitex rotundifolia L.f. USDA Plants Code: VIRO80 Common names: Roundleaf chastetree, beach vitex, chasteberry, monk's pepper Native distribution: Asia (China, Japan), India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Australia, Pacific Islands (inlcuding Hawaii) Date assessed: 3 June 2009; edited August 19, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: August 19, 2009 Form version date: 3 March 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank ( Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Present Moderate 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( 40 ) 37 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 ( 25 ) 20 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( 25 ) 4 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( 10 ) 8 Outcome score 100 ( 100 )b 73.00 a † Relative maximum score 73.00 § New York Invasiveness Rank High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

An Uninhabited, Undeveloped Barrier Island. (Under the Direction of Thomas R

ABSTRACT ROSENFELD, KRISTEN MARIE. Ecology of Bird Island, North Carolina: an uninhabited, undeveloped barrier island. (Under the direction of Thomas R. Wentworth.) Barrier islands include some of the most endangered and fragmented ecosystems on the Atlantic coast, providing critical habitat for many species, including some that are threatened and endangered. As the vast majority of these islands have been developed for human usage study and protection of the few remaining undeveloped and undisturbed islands is critical. This study was undertaken in order to characterize the vascular plant communities on Bird Island, an uninhabited, undeveloped barrier island on the border of North and South Carolina, with the objectives of a thorough survey of flora, vegetation, and environment, classification of plant communities, and multivariate analysis of vegetation and environmental data. A floristic inventory of the island and its associated marshes was conducted during the growing season (May- November) of 2002 and 2003. One hundred four 100m2 plots were inventoried for vegetation and environment using protocols developed by the Carolina Vegetation Survey. Plant communities were identified according to the National Vegetation Classification, the Classification of the Natural Communities of North Carolina, and the Carolina Vegetation Survey. Interpretation of vegetation patterns was based on multivariate analysis of vegetation and environmental data. Ninety-one vascular plant species in 35 families, including 4 exotic species, were distributed across 12 communities. Communities on Bird Island appear to be distinctive when compared to those described for other barrier islands in the region. Additionally, the vegetation survey on Bird Island revealed suitable habitat for the federally listed Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus); an important dune-building annual of the North American Atlantic coast. -

Population Genetics and Phylogenetic Context of Weed Evolution in the Genus Amaranthus: Amaranthaceae) Katherine Waselkov Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 8-12-2013 Population Genetics and Phylogenetic Context of Weed Evolution in the Genus Amaranthus: Amaranthaceae) Katherine Waselkov Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Waselkov, Katherine, "Population Genetics and Phylogenetic Context of Weed Evolution in the Genus Amaranthus: Amaranthaceae)" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1162. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1162 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Division of Biology and Biomedical Sciences Evolution, Ecology and Population Biology Dissertation Examination Committee: Kenneth M. Olsen, Chair James M. Cheverud Allan Larson Peter H. Raven Barbara A. Schaal Alan R. Templeton Population Genetics and Phylogenetic Context of Weed Evolution in the Genus Amaranthus (Amaranthaceae) by Katherine Elinor Waselkov A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by Katherine Elinor Waselkov. -

Dune Ecology: Beaches and Primary Dunes

Dune Ecology: Beaches and Primary Dunes Dunes are dynamic and constantly changing ecosystems plays a key role in mediating many of the ecosystems that form a natural buffer between sea and functions of dunes, including their growth and land. Depending on conditions, they can either stabilization. Similarly, the physical environment of accumulate sand from the beach, growing the dunes this unique habitat strongly shapes the ecology of the and storing sand, or they can form a source of sand to organisms living there. the beach as the dunes erode. e ecology of these Lower Beach and Wrack Line In the lower portion of the beach where sediments are (the base of what is known as the supratidal zone ), the covered frequently by water, aquatic organisms thrive. strand or wrack line forms a small oasis of life in the However, in the areas at and just above the high tide otherwise dry and relatively barren sand. Here in the zone, conditions are particularly harsh. e lack of wrack line, the debris left by the high tide forms a water makes life nearly impossible for aquatic or narrow band along the shore. As many a beachcomber terrestrial organisms, and the dry sand is easy to heat will testify, all kinds of items can be found here, from and cool, resulting in strong swings in temperature human garbage to seashells, animal remains, from too hot to walk on during a sunny summer day decomposing seaweed, sea grasses, and other natural to bitterly cold during winter. e sand in this area is materials. e rich organic content of this area moved by both wind and waves, creating a highly provides a reservoir of water and food for the animals dynamic system in which the sand is in near constant found in this area. -

Invasive Species Fact Sheet

HOW YOU CAN HELP INVASIVE SPECIES FACT SHEET Currently, an effort is being made by Mississippi State University, in cooperation with the South Carolina/North Carolina Beach Task Force, to determine the distribution of beach vitex in the Southeast and Mid-South. This infor- Beach vitex (Vitex Rotundifolia L.f.) mation which is being maintained in online databases by Mississippi State University (www.gri.msstate.edu) and Description, Distribution, and Management the South Carolina Beach Vitex Task Force (http://www.beachvitex.org), is very important in developing appropriate Victor Maddox, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Associate, Mississippi State University John D. Byrd, Jr., Ph.D., Extension/Research Professor, Mississippi State University strategies for addressing the plant. Please send reports of suspected beach vitex populations, including GPS coor- Randy Westbrooks, Ph. D., Invasive Species Specialist, U.S. Geological Survey dinates, site description / ownership, and photo images to: Victor Maddox, GeoResources Institute, Box 9555, Mis- Betsy Brabson, Ph. D., South Carolina Beach Vitex Task Force sissippi State, MS 39762-9652, Ph. 662-325-2123, E-mail: [email protected]; or to Betsy Brabson, South GRI Publication #5020 Carolina Beach Vitex Task Force, Georgetown, SC, Ph. 843-546-9531; E-mail: [email protected]. There are other ways to help with this effort, as well: INTRODUCTION Beach vitex (Vitex rotundifolia L.f.) is a deciduous woody • Do not plant beach vitex. Use native species such as sea oats. vine that was introduced to the Southeastern U.S. from • Remove beach vitex seedlings from public beach areas. Korea in the mid-1980s. Prior to its intoduction to the • Contact the GeoResources Institute for advice on removal of mature beach vitex colonies, and replacement with South Atlantic coast of the U.S., beach vitex had no native plant species. -

Sea-Beach Amaranth Amaranthus Pumilus Rafinesque

Endangered Plants of New Jersey Fact Sheet Sea-beach Amaranth Amaranthus pumilus Rafinesque Summary Sea-beach amaranth is an annual plant of the Amaranth family (Amaranthaceae) that exhibits low sprawling growth and small spinach-like leaves, and is restricted to open sandy portions of ocean beaches between the high tide line and the toe of the primary dune. It was first collected in the early Nineteenth Century in New Jersey, and its range was subsequently determined to extend from Massachusetts to South Carolina. Although originally described as abundant, the number of populations of A. pumilus declined precipitously throughout the Twentieth Century and, following a collection from Ocean County in 1913, vanished from the flora of New Jersey. Habitat destruction and alteration, incompatible beach grooming practices and recreational activities have all contributed to the decline of this species. By 1989, the species was restricted to a few populations in North and South Carolina. In 1991 New Jersey included A. pumilus in its first official Endangered Plant Species List, and in 1993 the U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, determined A. pumilus to be a federally threatened species under the authority of the Endangered Species Act. In 2000 the plant returned to newly created beaches in Monmouth County and adjacent habitat in Sandy Hook. Intensive surveys performed in 2001 revealed populations or individuals in all four coastal New Jersey counties. Despite its reappearance, the plant remains highly vulnerable to the uses and practices that caused its extirpation throughout most of the previous Century. Description following dispersal. Individuals are occasionally found on back dunes, exposed shoals, dune blowouts and bayside An annual plant that exhibits low, relatively prostrate strands, although these occurrences tend to be small and growth with fleshy, rounded, dark green leaves (1-2 cm temporary. -

Njplantlist.Pdf

List of Endangered Plant Species and Plant Species of Concern June 2016 Scientific Name Common Name G Rank S Rank Federal Status State Status Other Status Abies balsamea Balsam Fir G5 S1 E LP, HL Acorus americanus American Sweetflag G5 S1? HL Actaea rubra var. rubra Red Baneberry G5T5 S2 HL Adlumia fungosa Climbing Fumitory G4 S2 HL Aeschynomene virginica Sensitive Joint-vetch G2 S1 LT E LP, HL Agalinis auriculata Ear-leaf False Foxglove G3 SX HL Agalinis fasciculata Pine Barren Foxglove G5 S3 HL Agalinis paupercula var. paupercula Small-flower False Foxglove G5T5 S2 HL Agastache nepetoides Yellow Giant-hyssop G5 S2 HL Agastache scrophulariifolia Purple Giant-hyssop G4 S2 HL Agrimonia microcarpa Small-fruit Grooveburr G5 S2 HL Agrostis geminata Ticklegrass G5 S1? HL Alisma triviale Large Water-plantain G5 S1 E LP, HL Alopecurus aequalis var. aequalis Short-awn Meadow-foxtail G5T5 S2 HL Alopecurus carolinianus Tufted Meadow-foxtail G5 S3 HL Amaranthus pumilus Seabeach Amaranth G2 S1 LT E LP, HL Amelanchier humilis Low Service-berry G5 S1S2 HL Amelanchier nantucketensis Nantucket Service-berry G3Q S1 HL Amelanchier sanguinea var. sanguinea Round-leaf Service-berry G5T5 S1.1 E LP, HL Amelanchier stolonifera Running Service-berry G5 S3 HL Amianthium muscitoxicum Fly Poison G4G5 S2 HL Ammannia latifolia Koehn's Toothcup G5 S1 E LP, HL Andromeda polifolia var. glaucophylla Bog Rosemary G5T5 S1 E LP, HL Andropogon glomeratus var. hirsutior Hairy Beardgrass G5T5 SH.1 HL Andropogon gyrans Elliott's Beardgrass G5 S2 HL Andropogon ternarius var. ternarius Silvery Beardgrass G5T5? S2 HL Anemone canadensis Canada Anemone G5 SX HL Anemone cylindrica Long-head Anemone G5 S1 E LP, HL Anemone virginiana var. -

Surveys for the Federally-Listed Threatened Plant Species, Seabeach Amaranth (Amaranthus Pumilus), in Keansburg, NJ

Surveys for the Federally-Listed Threatened Plant Species, Seabeach Amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus), in Keansburg, NJ May 19, 2012 Jay F. Kelly, Ph.D. Round Mountain Ecological LLC 74 Old Highway 28 Whitehouse Station, NJ 08889 [email protected] (908) 534-0053 Introduction Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus Raf.) is an herbaceous annual plant in the Amaranthaceae that occurs on sandy, ocean beaches in eastern North America. The habitat of A. pumilus is restricted to the narrow strip of land between the high tide line and the base of the dunes, and significant impacts to these areas by coastal development, hard shoreline stabilization, incompatible land use practices, and severe storms have resulted in major declines in the species’ populations throughout its range (USFWS 1996). The species is currently listed as Threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS 1996), and Endangered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP 2010). Although there are no historic records documenting the presence of seabeach amaranth in Keansburg, NJ, this portion of the Raritan Bay contains ample suitable habitat for the species and is in close proximity to the largest populations of the species in the State, in Sandy Hook. Although surveys of these areas in 2010-2011 found no A. pumilus, the exceptional seed banking and dispersal capabilities of this annual plant species make repeated surveys necessary to effectively document the presence or absence of the species in a given area. Results - Amaranthus pumilus This report presents the results of surveys conducted for seabeach amaranth in Keansburg, NJ, prior to the beach replenishment planned for May 2012. -

Vitex Rotundifolia Global Invasive Species Database (GISD)

FULL ACCOUNT FOR: Vitex rotundifolia Vitex rotundifolia System: Terrestrial Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Plantae Magnoliophyta Magnoliopsida Lamiales Verbenaceae Common name dan ye man jing (Chinese, China), roundleaf chastetree (English), single-leaf chaste tree (English), kolokolo kahakai (Hawaiian, Hawaii), chasteberry (English), pohinahina (Hawaiian, Hawaii), mawanawana (Hawaiian, Hawaii), beach vitex (English), polinalina (Hawaiian, Hawaii), hinahina kolo (Hawaiian, Hawaii), man hyung ja (English, Korea), manawanawa (Hawaiian, Hawaii), cloister pepper (English), monk's pepper (English), hamago (English, Japan) Synonym Vitex ovata , (Thunb.) Vitex trifolia , var. simplicifolia (Cham.) Vitex agnus-castus , var. ovata (Thunb.) Makino Vitex trifolia , subsp. litoralis Steenis Vitex trifolia , var. obovata Bentham Vitex trifolia , var. ovata (Thunb.) Makino Vitex trifolia , var. ovata (Thunb.) Merrill Vitex trifolia , var. unifoliata Schauer Vitex trifolia , var. repens Ridley Vitex repens , Blanco Similar species Morella cerifera, Cakile edentula ssp. harperi, Croton punctatus, Amaranthus pumilus, Iva frutescens, Iva imbricata Summary Vitex rotundifolia, also commonly known as beach vitex, is a perennial woody shrub of coastal sand dunes of Asia and the Pacific islands. It has been introduced into the United States where it is an invasive exotic plant. Vitex rotundifolia has a strong impact on the native flora and fauna along the United States Carolina coast, shading native plants and disrupting nesting sites for sea turtles. Active community involvement and strategic mapping and eradication efforts are underway to limit the extent and impact that this exotic species has on the coasts of the Carolinas and prevent it from spreading into a wider geographical range. view this species on IUCN Red List Global Invasive Species Database (GISD) 2021.