History As Policy Framing the Debate on the Future of Australia’S Defence Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

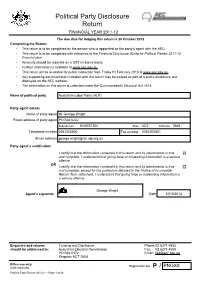

Political Party Return for 2011-12

Political Party Disclosure Return FINANCIAL YEAR 2011-12 The due date for lodging this return is 20 October 2012 Completing the Return: • This return is to be completed by the person who is appointed as the party’s agent with the AEC. • This return is to be completed with reference to the Financial Disclosure Guide for Political Parties 2011-12 financial year. • Amounts should be reported on a GST inclusive basis. • Further information is available at www.aec.gov.au. • This return will be available for public inspection from Friday 01 February 2013 at www.aec.gov.au. • Any supporting documentation included with this return may be treated as part of a public disclosure and displayed on the AEC website. • The information on this return is collected under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. Name of political party Australian Labor Party (ALP) Party agent details Name of party agent Mr George Wright Postal address of party agent PO Box 6222 Suburb/town KINGSTON State ACT Postcode 2604 Telephone number 0261200800 Fax number 0261200801 Email address [email protected] Party agent’s certification I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true þ and complete. I understand that giving false or misleading information is a serious offence OR I certify that the information contained in this return and its attachments is true o and complete, except for the particulars detailed in the ‘Notice of Incomplete Return’ form (attached). I understand that giving false or misleading information is a serious offence. -

Periodicals and Recurring Documents

PERIODICALS AND RECURRING DOCUMENTS May 2012 Legend A ANNUAL S-M SEMI-MONTHLY D DAILY BI-M BI-MONTHLY W WEEKLY Q QUARTERLY BI-W BI-WEEKLY TRI-A TRI-ANNUAL M MONTHLY IRR IRREGULAR S-A SEMI-ANNUAL A ACADEME. (BI-M) 1985-1989 ACADEMY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE. PROCEEDINGS. (IRR) 1960-1991 (MFILM 1975-1980) (MFICHE 1981-1982) ACQUISITION REVIEW QUARTERLY. (Q) 1994-2003 CONTINUED BY DEFENSE ACQUISITION REVIEW JOURNAL. AD ASTRA-TO THE STARS. (M) 1989-1992 ADA. (Q) 1991-1997 FORMERLY AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY. ADF: AFRICA DEFENSE FORUM. (Q) 2008- ADVANCE. (A) 1986-1994 ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. SEE S.A.M. ADVANCED MANAGEMENT JOURNAL. ADVISOR. (Q) 1974-1978 FORMERLY JOURNAL OF NAVY CIVILIAN MANPOWER MANAGEMENT. ADVOCATE. (BI-M) 1982-1984 - 1 - AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1977-1978 CONTINUED BY AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. AEI FOREIGN POLICY AND DEFENSE REVIEW. (BI-M) 1979-1986 FORMERLY AEI DEFENSE REVIEW. AEROSPACE. (Q) 1963-1987 AEROSPACE AMERICA. (M) 1984-1998 FORMERLY ASTRONAUTICS & AERONAUTICS. AEROSPACE AND DEFENSE SCIENCE. (Q) 1990-1991 FORMERLY DEFENSE SCIENCE. AEROSPACE HISTORIAN. (Q) 1965-1988 FORMERLY AIRPOWER HISTORIAN. CONTINUED BY AIR POWER HISTORY. AEROSPACE INTERNATIONAL. (BI-M) 1967-1981 FORMERLY AIR FORCE SPACE DIGEST INTERNATIONAL. AEROSPACE MEDICINE. (M) 1973-1974 CONTINUED BY AVIATION SPACE AND EVIRONMENTAL MEDICINE. AEROSPACE POWER JOURNAL. (Q) 1999-2002 FORMERLY AIRPOWER JOURNAL. CONTINUED BY AIR & SPACE POWER JOURNAL. AEROSPACE SAFETY. (M) 1976-1980 AFRICA REPORT. (BI-M) 1967-1995 (MFICHE 1979-1994) AFRICA TODAY. (Q) 1963-1990; (MFICHE 1979-1990) 1999-2007 AFRICAN SECURITY. (Q) 2010- AGENDA. (M) 1978-1982 AGORA. -

The Secret Life of Elsie Curtin

Curtin University The secret life of Elsie Curtin Public Lecture presented by JCPML Visiting Scholar Associate Professor Bobbie Oliver on 17 October 2012. Vice Chancellor, distinguished guests, members of the Curtin family, colleagues, friends. It is a great honour to give the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library’s lecture as their 2012 Visiting Scholar. I thank Lesley Wallace, Deanne Barrett and all the staff of the John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library, firstly for their invitation to me last year to be the 2012 Visiting Scholar, and for their willing and courteous assistance throughout this year as I researched Elsie Curtin’s life. You will soon be able to see the full results on the web site. I dedicate this lecture to the late Professor Tom Stannage, a fine historian, who sadly and most unexpectedly passed away on 4 October. Many of you knew Tom as Executive Dean of Humanities from 1999 to 2005, but some years prior to that, he was my colleague, mentor, friend and Ph.D. supervisor in the History Department at UWA. Working with Tom inspired an enthusiasm for Australian history that I had not previously known, and through him, I discovered John Curtin – and then Elsie Curtin, whose story is the subject of my lecture today. Elsie Needham was born at Ballarat, Victoria, on 4 October 1890 – the third child of Abraham Needham, a sign writer and painter, and his wife, Annie. She had two older brothers, William and Leslie. From 1898 until 1908, Elsie lived with her family in Cape Town, South Africa, where her father had established the signwriting firm of Needham and Bennett. -

Australia's Strategic Culture and Constraints in Defence

International Studies Association – Annual Convention 2013 Australia’s Strategic Culture and Constraints in Defence and National Security Policymaking Alex Burns, PhD Candidate, Monash University ([email protected]) Ben Eltham, PhD Candidate, University of Western Sydney ([email protected]) Abstract Scholars have advanced different conceptualisations of Australia’s strategic culture. Collectively, this work contends Australia is a ‘middle power’ nation with a realist defence policy, elite discourse, entrenched military services, and a regional focus. This paper contends that Australia’s strategic culture has unresolved tensions due to the lack of an overarching national security framework, and policymaking constraints at two interlocking levels: cultural worldviews and institutional design that affects strategy formulation and resource allocation. The cultural constraints include confusion over national security policy, the prevalence of neorealist strategic studies, the Defence Department’s dominant role in formulating strategic doctrines, and problematic experiences with Asian ‘regional engagement’ and the Pacific Islands. The institutional constraints include resourcing, inter-departmental coordination, a narrow approach to government white papers, and barriers to long-term strategic planning. In this paper, we examine possibilities for continuity and change, including the Gillard Government’s Asian Century White Paper, National Security Strategy and the forthcoming 2013 Defence White Paper. Introduction Digging Up Silos in Australia’s National Security Community On 23rd January 2013, the Gillard Government released Australia’s first National Security Strategy (NSS): Strong and Secure: A Strategy for Australia’s National Security.1 Amongst the NSS initiatives was a new Australian Cyber Security Centre that would coordinate Australian Federal Government expertise to combat cyber-attacks and cybercrime, provide cybersecurity and to strengthen the National Broadband Network’s rollout. -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Indigenous Australians Brochure

SEE YOURSELF IN A REWARDING ROLE CHOOSE A JOB IN A DIVERSE AND SUPPORTIVE WORKPLACE A CONTRIBUTE TO YOUR COUNTRY’S DEFENCE THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE (ADF) IS AN EMPLOYER OF CHOICE FOR HUNDREDS OF INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS. Help maintain a proud tradition of service by joining the thousands of Indigenous men and women who for over 100 years, have contributed to the protection of our country and its interests as members of the ADF. In the Navy, Army or Air Force, you’ll work alongside Indigenous Australians from across the ranks, enjoying opportunities rarely found in civilian employment. As you serve your country and community, your abilities will be nurtured and given focus. You’ll receive world-class training and be given the opportunity to earn qualifications that will give you the skills, knowledge and experience to reach your full potential in a fulfilling role. 01 FEATURED 04 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE 08 RECEIVE WORLD-CLASS TRAINING INSIDE AND EDUCATION 09 CHOOSE YOUR IDEAL ROLE 10 ENTER THE WAY YOU WANT TO 14 ACHIEVE YOUR POTENTIAL 16 INDIGENOUS PRE-RECRUIT PROGRAM 18 NAVY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 20 ARMY INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM 22 AIR FORCE INDIGENOUS DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES 26 ACCESS FLEXIBLE ENTRY PATHWAYS 28 HOW TO JOIN 32 CONTACT US 02 03 GET A GREAT JOB AND MORE REWARDING, WELL-PAID WORK IS JUST THE START. AS A FULL-TIME MEMBER OF THE ADF YOU’LL ENJOY: A friendly and supportive team environment that embraces cultural, social and workforce diversity A competitive salary and superannuation Equal pay regardless -

Case Study Australia 108, Melbourne

Case Study Australia 108, Melbourne CoxGomyl delivers a complete facade access solution for the tallest residential tower in Australia Australia 108 is the tallest residential tower in the Southern Hemisphere by height to the roof, surpassing Eureka Tower and Queensland’s Q1 Tower. The bold and imaginative design by Fender Katsalidis Architects, towers 320 metres and 100 stories over Melbourne’s famous Southbank precinct. Facts & Figures Beyond the sheer scale of the building, the complex aesthetic is inspired by the Commonwealth Star of the Australian flag with a unique golden ‘starburst’ feature projecting out from the slender, curving form of the tower across levels 69 to 72. Commencement 2020 The ambitious scale of the building and its complex geography required the Completion 2020 experience and expertise of CoxGomyl as market leaders in facade access solutions in order to ensure practical, reliable access coverage and safeguard Building Height 320m the well being of the tower for years into the future. The comprehensive building access system developed by the CoxGomyl Floor Count 100 team is made up of five Building Maintenance Units working in harmony to provide all of the required coverage and functionality. The first BMU is No. of BMUs 5 located in a fixed position at roof level which services the area from the top of the building to the bottom of the starburst feature. With a reach of nearly 34 metres and a system of mullion guides which allow operators to manoeuvre Outreach Up to 33.94m the cradle out from the main facade surface, this challenging feature is made conveniently accessible. -

The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 Karl James University of Wollongong James, Karl, The final campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2005. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/467 The Final Campaigns: Bougainville 1944-1945 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Karl James, BA (Hons) School of History and Politics 2005 i CERTIFICATION I, Karl James, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, is wholly my work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Karl James 20 July 2005 ii Table of Contents Maps, List of Illustrations iv Abbreviations vi Conversion viii Abstract ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1 ‘We have got to play our part in it’. Australia’s land war until 1944. 15 2 ‘History written is history preserved’. History’s treatment of the Final Campaigns. 30 3 ‘Once the soldier had gone to war he looked for leadership’. The men of the II Australian Corps. 51 4 ‘Away to the north of Queensland, On the tropic shores of hell, Stand grimfaced men who watch and wait, For a future none can tell’. The campaign takes shape: Torokina and the Outer Islands. -

Assembly December Weekly Book 1 2006

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-SIXTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 19 and 20 December 2006 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor Professor DAVID de KRETSER, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier, Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Minister for Veterans’ Affairs.............................................. The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Water, Environment and Climate Change...................................................... The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Education............................................ The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Skills, Education Services and Employment and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Gaming, Minister for Consumer Affairs and Minister assisting the Premier on Multicultural Affairs ..................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Minister for Victorian Communities and Minister for Energy and Resources.................................................... The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Treasurer, Minister for Regional and Rural Development and Minister for Innovation......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services and Minister for Corrections................................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Agriculture.......................................... -

The Legacy of Robert Menzies in the Liberal Party of Australia

PASSING BY: THE LEGACY OF ROBERT MENZIES IN THE LIBERAL PARTY OF AUSTRALIA A study of John Gorton, Malcolm Fraser and John Howard Sophie Ellen Rose 2012 'A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of BA (Hons) in History, University of Sydney'. 1 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to acknowledge the guidance of my supervisor, Dr. James Curran. Your wisdom and insight into the issues I was considering in my thesis was invaluable. Thank you for your advice and support, not only in my honours’ year but also throughout the course of my degree. Your teaching and clear passion for Australian political history has inspired me to pursue a career in politics. Thank you to Nicholas Eckstein, the 2012 history honours coordinator. Your remarkable empathy, understanding and good advice throughout the year was very much appreciated. I would also like to acknowledge the library staff at the National Library of Australia in Canberra, who enthusiastically and tirelessly assisted me in my collection of sources. Thank you for finding so many boxes for me on such short notice. Thank you to the Aspinall Family for welcoming me into your home and supporting me in the final stages of my thesis and to my housemates, Meg MacCallum and Emma Thompson. Thank you to my family and my friends at church. Thank you also to Daniel Ward for your unwavering support and for bearing with me through the challenging times. Finally, thanks be to God for sustaining me through a year in which I faced many difficulties and for providing me with the support that I needed. -

Defence Policy-Making

Chapter 1 The Road to Russell A career in the Public Service which closed after a decade as Secretary to the Department of Defence started from what might seem an unlikely origin. In 1942, aged 28, I was brought to Canberra from a wartime reserved occupation to work on analysing Australia's interests in the international economic and financial regulations being proposed for Australia's responses by the British and American planners who were preparing for a better world system after the war had been won. For a short period I was made responsible to Dr Roland Wilson (later Secretary to the Treasury), but in 1943 the Labor Government created the Department of Post-War Reconstruction, with J.B. Chifley as its Minister (and concurrently Treasurer) and Dr H.C. `Nugget' Coombs as its Director-General. I worked under Coombs for several years, preparing papers and advice for several of Australia's most senior economists on the problems to be expected, and the safeguards needed, to protect Australia in the impact of these post-war plans of the two major economic powers. Over the years, I attended several international conferences arranged to discuss and to amend and endorse these plans, beginning with the 1944 Bretton Woods International Monetary Conference. External Affairs 1945 I was seconded into the Department of External Affairs in 1945. That Department, under the urging of Dr J.W. Burton, was seeking a role in policy in these economic fields, particularly with the prospect of the United Nations and other institutions being set up with various regulatory powers.