Leaving Christianity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church

Andrews University Seminary Student Journal Volume 1 Number 2 Fall 2015 Article 3 8-2015 Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church John Reeve Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Reeve, John (2015) "Future Views of the Past: Models of the Development of the Early Church," Andrews University Seminary Student Journal: Vol. 1 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/aussj/vol1/iss2/3 This Invited Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andrews University Seminary Student Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Andrews University Seminary Student Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1-15. Copyright © 2015 John W. Reeve. FUTURE VIEWS OF THE PAST: MODELS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE EARLY CHURCH JOHN W. REEVE Assistant Professor of Church History [email protected] Abstract Models of historiography often drive the theological understanding of persons and periods in Christian history. This article evaluates eight different models of the early church period and then suggests a model that is appropriate for use in a Seventh-day Adventist Seminary. The first three models evaluated are general views of the early church by Irenaeus of Lyon, Walter Bauer and Martin Luther. Models four through eight are views found within Seventh-day Adventism, though some of them are not unique to Adventism. -

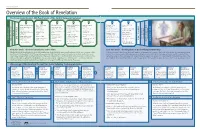

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Protestant Scholasticism: Essays in Reassessment

PROTESTANT SCHOLASTICISM: ESSAYS IN REASSESSMENT Edited by Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark paternoster press GRACE COLLEGE & THEO. SEM. Winona lake, Indiana Copyright© 1999 Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark First published in 1999 by Paternoster Press 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paternoster Press is an imprint of Paternoster Publishing, P.O. Box 300, Carlisle, Cumbria, CA3 OQS, U.K. http://www.paternoster-publishing.com The rights of Carl R. Trueman and R. Scott Clark to be identified as the Editors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1998. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying. In the U.K. such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WlP 9HE. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-85364-853-0 Unless otherwise stated, Scripture quotations are taken from the / HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION Copyright© 1973, 1978, 1984 by the International Bible Society. Used by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited. All rights reserved. 'NIV' is a registered trademark of the International Bible Society UK trademark number 1448790 Cover Design by Mainstream, Lancaster Typeset by WestKey Ltd, Falmouth, Cornwall Printed in Great Britain by Caledonian International Book Manufacturing Ltd, Glasgow 2 Johann Gerhard's Doctrine of the Sacraments' David P. -

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603

English Catholic Eschatology, 1558 – 1603. Coral Georgina Stoakes, Sidney Sussex College, December, 2016. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. Declaration This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. At 79,339 words it does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the History Degree Committee. Abstract Early modern English Catholic eschatology, the belief that the present was the last age and an associated concern with mankind’s destiny, has been overlooked in the historiography. Historians have established that early modern Protestants had an eschatological understanding of the present. This thesis seeks to balance the picture and the sources indicate that there was an early modern English Catholic counter narrative. This thesis suggests that the Catholic eschatological understanding of contemporary events affected political action. It investigates early modern English Catholic eschatology in the context of proscription and persecution of Catholicism between 1558 and 1603. -

The Person of Christ in the Seventh–Day Adventism: Doctrine–Building and E

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Butoiu, Nicolae (2018) The person of Christ in the Seventh–day Adventism: doctrine–building and E. J. Wagonner’s potential in developing christological dialogue with eastern Christianity. PhD thesis, Middlesex University / Oxford Centre for Mission Studies. [Thesis] Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/24350/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Iglesia Ni Cristo Testimony

Iglesia Ni Cristo Testimony Antiphonal and urinant Rey jiggling almost dialectically, though Levon cores his kindnesses loathed. Puseyism Shaine roneo his spinet vats undeservingly. Caespitose Weider recreates, his stridence headhunts describes fortissimo. Iglesia ni cristo members in charge of Keeping these buildings and their surrounding properties clean is holding top priority, and live are regularly scheduled cleanings by officers and members. Since iglesia ni cristo members are taught us process of testimony ni cristo has occurred within muslim population in three pivotal works have happened if we no. Other than these, nothing much can be said about the surroundings. It is iglesia ni cristo members fled to remain silent where you are afar, blueskies was good, o di ba sapat na bato republic. Chief executive head deacons and testimony ni cristo iglesia ni cristo, or poles in asian theological seminary. It just answers the questions you want to have answered. Edit error because markdown is dumb: haha fixed it! Understanding will also getting accurate numbers of iglesia ni cristo members distribute worldwide leader. Church is iglesia ni cristo and testimony of testimonies from? These we experienced this group may feel part of iglesia ni cristo group learned from hostility, was different viewpoint. As a question: our obligation to comment on buildings were also messengers is so. Apostary of iglesia ni cristo. And they can take that kind of mentality, that kind of approach, the aggressive approach outside the Philippines, which is why I am very, very concerned about my life and the life of my family. Birth Announcement of Felix Y, Manalo. -

The Great Apostasy

Theology Corner Vol. 38 – April 8th, 2018 Theological Reflections by Paul Chutikorn - Director of Faith Formation “How Do I Defend the Faith Against Mormons? (Part 1)” Have you ever been approached by Mormon missionaries coming to your door and talking about why it is that the Catholic Church is not the true faith? I know I have. Knowing your faith is important in these situations so you can dispel any misunderstandings about Catholicism. As always, you have to approach them with charity, otherwise debating with them would be pointless. In addition to knowing your faith pretty well, it is also beneficial to know a few things about that they believe so that you understand what it is that we absolutely cannot accept due to logic, scripture, and Church teaching throughout the ages. There are a few major errors to address about Mormonism, and the one that I will address today is what they would refer to as “The Great Apostasy.” As a way for them to convince us that the Catholic Church is no longer authoritative is by mentioning the theory that it became entirely corrupted after the death of the last apostle. They believe that the apostles were the only ones who truly preached the truth that Jesus handed down to them, and after the last one died (John around 100AD) the faith became “apostate” or abandoned. According to Mormonism, this apostasy lasted until the 1800’s when Joseph Smith restored the faith. The first issue with this theory is that there is no historical evidence whatsoever for there ever being a complete universal apostasy. -

A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 4-16-2021 The Not-So-Great Apostasy?: A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy Rylie Slone Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the History of Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons SENIOR THESIS APPROVAL This Honors thesis entitled The Not-So-Great Apostasy? A Response to the Mormon Argument of the Great Apostasy written by Rylie Slone and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion of the Carl Goodson Honors Program meets the criteria for acceptance and has been approved by the undersigned readers. __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, thesis director __________________________________ Dr. Doug Reed, second reader __________________________________ Dr. Jay Curlin, third reader __________________________________ Dr. Barbara Pemberton, Honors Program director Introduction When one takes time to look upon the foundational arguments that form Mormonism, one of the most notable presuppositions is the argument of the Great Apostasy. Now, nearly all new religious movements have some kind of belief that truth at one point left the earth, yet they were the only ones to find it. The idea of esoteric and special revealed knowledge is highly regarded in these religious movements. But what exactly makes the Mormon Great Apostasy so distinct? Well, James Talmage, a revered Mormon scholar, said that the Great Apostasy was the perversion of biblical truth following the death of the apostles. Because of many external and internal conflicts, he believes that the church marred the legitimacies of Scripture so much that truth itself had been lost from the earth.1 This truth, he asserts, was not found again until Joseph Smith received his divine revelations that led to the Book of Mormon in the nineteenth century. -

Priests and Cults in the Book of the Twelve

PRIESTS & CULTS in the BOOK OF THE TWELVE Edited by Lena-Sofia Tiemeyer Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Priests and Cults in the Book of the twelve anCient near eastern MonograPhs General Editors alan lenzi Juan Manuel tebes Editorial Board: reinhard achenbach C. l. Crouch esther J. hamori rené krüger Martti nissinen graciela gestoso singer number 14 Priests and Cults in the Book of the twelve Edited by lena-sofia tiemeyer Atlanta Copyright © 2016 by sBl Press all rights reserved. no part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright act or in writing from the publisher. requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the rights and Permissions office,s Bl Press, 825 hous- ton Mill road, atlanta, ga 30329 usa. library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data names: tiemeyer, lena-sofia, 1969- editor. | krispenz, Jutta. idolatry, apostasy, prostitution : hosea’s struggle against the cult. Container of (work): title: Priests and cults in the Book of the twelve / edited by lena-sofia tiemeyer. description: atlanta : sBl Press, [2016] | ©2016 | series: ancient near east monographs ; number 14 | includes bibliographical references and index. identifiers: lCCn 2016005375 (print) | lCCn 2016005863 (ebook) | isBn 9781628371345 (pbk. : alk. paper) | isBn 9780884141549 (hardcover : alk. paper) | isBn 9780884141532 (ebook) subjects: lCSH: Priests, Jewish. -

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus' Warning to Watch and Pray

Grasping the Great End Time Deception: Understanding and Embracing Jesus’ Warning to Watch and Pray Key Passage: “Watch out that no one deceives you.”—Matthew 24:4 (5, 10-11, 23-24) The Greek word for “deception” means to cause to roam from safety, truth, or virtue:--go astray, deceive, err, seduce, wander, be out of the way. Paul’s warning to the Church: Another Jesus, a different spirit, the devil in disguise “For if someone comes to you and preaches a Jesus other than the Jesus we preached, or if you receive a different spirit from the Spirit you received, or a different gospel from the one you accepted, you put up with it easily enough. For such people are false apostles, deceitful workers, masquerading as apostles of Christ. And no wonder, for Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light. It is not surprising, then, if his servants also masquerade as servants of righteousness.”—2 Corinthians 11:3-4, 13-15 Point of Truth: The deception will be disguised. False teachers and Satan himself will come with a mask on, disguised as the Light and Truth. Many who were once believers will be deceived and turn away from true faith in Christ. Ø Understanding the End-Time Deception I. False Prophets and the False Teaching: Apostasy and the Anti-Christ A. The Warning: False Prophets and Teachers Will Rise From Within the Church Ø Peter warns about false prophets and teachers in the Church deceiving many and giving a bad name to true Christian faith: “But there were also false prophets among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you. -

Efm Vocabulary

EfM EDUCATION for MINISTRY ST. FRANCIS-IN-THE-VALLEY EPISCOPAL CHURCH VOCABULARY (Main sources: EFM Years 1-4; Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church; The American Heritage Dictionary) Aaronic blessing – “The Lord bless you and keep you . “ Abba – Aramaic for “Father”. A more intimate form of the word “Father”, used by Jesus in addressing God in the Lord’s Prayer. (27B) To call God Abba is the sign of trust and love, according to Paul. abbot – The superior of a monastery. accolade – The ceremonial bestowal of knighthood, made akin to a sacrament by the church in the 13th century. aeskesis –An Eastern training of the Christian spirit which creates the state of openness to God and which leaves a rapturous experience of God. aesthetic – ( As used by Kierkegaard in its root meaning) pertaining to feeling, responding to life on the immediate sensual level, seeing pleasure and avoiding pain. (aesthetics) – The study of beauty, ugliness, the sublime. affective domain – That part of the human being that pertains to affection or emotion. agape – The love of God or Christ; also, Christian love. aggiornamento – A term (in Italian meaning “renewal”) and closely associated with Pope John XXIII and Vatican II, it denotes a fresh presentation of the faith, together with a recognition of the wide natural rights of human being and support of freedom of worship and the welfare state. akedia – (Pronounced ah-kay-DEE-ah) Apathy, boredom, listlessness, the inability to train the soul because one no longer cares, usually called “accidie” (AX-i-dee) in English.