Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighbourhood Dog Park in Downtown Winnipeg

NEIGHBOURHOOD DOG PARK IN DOWNTOWN WINNIPEG WELCOME! Please participate today by: 1. Viewing the story boards for an update 4. Asking questions and talking with the on the project consultants & City of Winnipeg staff 2. Finding out what we heard from the 5. Providing input at our site selection online survey map station 3. Reviewing preferred Neighbourhood Dog Park 6. Providing feedback on a survey about site options in Downtown Winnipeg this event neighbourhood dog park in downtown winnipeg PROJECT SCOPE & TIMELINE The City of Winnipeg has recognized the need for a Neighbourhood off-leash dog park in Downtown Winnipeg Benefits of a Neighbourhood Downtown Dog Park include: • Increases accessibility of dog ownership in downtown, • Encourages downtown living, • Builds strong community ties by fostering opportunities for socialization, • Provides a designated space for dogs to safely exercise Source: http:// www.tompkinssquaredogrun.com and play with other dogs Tompkins Square, New York NOVEMBER - DECEMBER 2015 JANUARY 07-20, 2016 TODAY SPRING 2016 SUMMER/FALL 2016 BACKGROUND ONLINE PUBLIC PUBLIC • SITE SELECTION NEIGHBOURHOOD RESEARCH AND SURVEY OPEN HOUSE • DETAILED DESIGN DOG PARK STAKEHOLDER + • TENDER CONSTRUCTION MEETINGS 1828 WE ARE HERE PARTICIPANTS * * DOG PARKS IN WINNIPEG Existing Dog Parks in Winnipeg Dog Park Classification and Proximity to Users Source: Guidelines for off-leash Dog Parks in the city of Winnipeg Regional Dog Park: • A large destination park that attracts many users 1 • Typically accessed by car and provides parking 1 2 1 9 2 Community Dog Park: 11 7 2 • Attracts local users associated with a cluster of 8 9 6 neighbourhoods 1 5 5 Source: http://northkildonanrealestate.wordpress.com 7 6 7 Kil-Cona Park - Regional • Accessed by walking and/or car, and may provide 8 11 10 2 9 5 parking 10 4 6 9 11 7 Neighbourhood Dog Park: 8 10 5 • A small local park that serves a specific area 3 6 8 of residents 4 11 RegionalRegional: Dog Park 8ha+ (8+ Hectares) 3 • Typically within 5-10 minute walking distance of user 1. -

River Road to Rivergate Drive Study Recommendations

MORE PEOPLE BIKING MORE OFTEN River Road to Rivergate Drive Study Recommendations Given the poor lack of north/south connectivity between River Road and the Henteleff Park/South St. Vital Trail corridor, a pathway along the Red River connecting the Minnetonka and Normand Park neigbourhoods would be a positive addition to Winnipeg’s bicycle network. Ultimately, we feel that this pathway could be extended south to Maple Grove Park. Of course, any investment in a pathway connection along the Red River will need to maximize connections to the local and regional bicycle network, and to neighbourhood, community, and regional destinations. We feel that the benefits of this project would be greatly increased by improving walking and cycling connections to St. Amant Centre, Minnetonka School and Park, Greendell Park Community Centre, and Darwin School & Park. Ideally, the planned pathway would also provide a spur giving access across St. Mary’s Road into Dakota Park and the River Park South neighbouhood, but given potential rights of way and their distance from existing traffic signals on St. Mary’s Road, this may not be achievable. Without a signalized crossing of St. Mary’s Road and access through the Okolita Park development into Dakota Park, we feel that the missing connections to St. Amant Cenre, Minnetonka School and Park, and Greendell Park Community Centre should take priority over any connection to St. Mary’s Road. P.O. Box 162 Corydon Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3M 3S7 · Ph: 204-894-6540 · [email protected] · www.bikewinnipeg.ca 1 Key Recommendations 1. We prefer Option 2 over Option 1 as the more comfortable and attractive option, but with the addition of a connection to the Village Canadien driveway as per Option 1 a. -

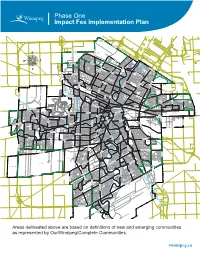

Impact Fee Implementation Plan

Phase One Impact Fee Implementation Plan ROSSER-OLD KILDONAN AMBER TRAILS RIVERBEND LEILA NORTH WEST KILDONAN INDUSTRIAL MANDALAY WEST RIVERGROVE A L L A TEMPLETON-SINCLAIR H L A NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL INKSTER GARDENS THE MAPLES V LEILA-McPHILLIPS TRIANGLE RIVER EAST MARGARET PARK KILDONAN PARK GARDEN CITY SPRINGFIELD NORTH INKSTER INDUSTRIAL PARK TYNDALL PARK JEFFERSON ROSSMERE-A KILDONAN DRIVE KIL-CONA PARK MYNARSKI SEVEN OAKS ROBERTSON McLEOD INDUSTRIAL OAK POINT HIGHWAY BURROWS-KEEWATIN SPRINGFIELD SOUTH NORTH TRANSCONA YARDS SHAUGHNESSY PARK INKSTER-FARADAY ROSSMERE-B BURROWS CENTRAL ST. JOHN'S LUXTON OMAND'S CREEK INDUSTRIAL WESTON SHOPS MUNROE WEST VALLEY GARDENS GRASSIE BROOKLANDS ST. JOHN'S PARK EAGLEMERE WILLIAM WHYTE DUFFERIN WESTON GLENELM GRIFFIN TRANSCONA NORTH SASKATCHEWAN NORTH DUFFERIN INDUSTRIAL CHALMERS MUNROE EAST MEADOWS PACIFIC INDUSTRIAL LORD SELKIRK PARK G N LOGAN-C.P.R. I S S NORTH POINT DOUGLAS TALBOT-GREY O R C PEGUIS N A WEST ALEXANDER N RADISSON O KILDARE-REDONDA D EAST ELMWOOD L CENTENNIAL I ST. JAMES INDUSTRIAL SOUTH POINT DOUGLAS K AIRPORT CHINA TOWN C IVIC CANTERBURY PARK SARGENT PARK CE TYNE-TEES KERN PARK NT VICTORIA WEST RE DANIEL McINTYRE EXCHANGE DISTRICT NORTH ST. BONIFACE REGENT MELROSE CENTRAL PARK SPENCE PORTAGE & MAIN MURRAY INDUSTRIAL PARK E TISSOT LLIC E-E TAG MISSION GARDENS POR TRANSCONA YARDS HERITAGE PARK COLONY SOUTH PORTAGE MISSION INDUSTRIAL THE FORKS DUGALD CRESTVIEW ST. MATTHEWS MINTO CENTRAL ST. BONIFACE BUCHANAN JAMESWOOD POLO PARK BROADWAY-ASSINIBOINE KENSINGTON LEGISLATURE DUFRESNE HOLDEN WEST BROADWAY KING EDWARD STURGEON CREEK BOOTH ASSINIBOIA DOWNS DEER LODGE WOLSELEY RIVER-OSBORNE TRANSCONA SOUTH ROSLYN SILVER HEIGHTS WEST WOLSELEY A NORWOOD EAST STOCK YARDS ST. -

2015 Report on Park Assets

Appendix A 2015 Report on Park Assets Asset Management Branch Parks and Open Space Division Public Works Department Table of Contents Summary of Parks, Assets and Asset Condition by Ward Charleswood-Tuxedo-Whyte Ridge Ward ................................................................................................... 1 Daniel McIntyre Ward .................................................................................................................................. 9 Elmwood – East Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................. 16 Fort Rouge – East Fort Garry Ward ............................................................................................................ 24 Mynarski Ward ........................................................................................................................................... 32 North Kildonan Ward ................................................................................................................................. 40 Old Kildonan Ward ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Point Douglas Ward.................................................................................................................................... 56 River Heights – Fort Garry Ward ................................................................................................................ 64 South Winnipeg – St. Norbert -

Property Taxes and Built Form: Mapping the City of Winnipeg By: Felipe A

Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg$ X.xx - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Win- nipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg Winnipeg - Winnipeg - Winnipeg - -

WARDS BOUNDARIES COMMISSION - File GL – 5.1

WARDS BOUNDARIES COMMISSION - File GL – 5.1 Communication dated August 24, 2017, from Lisa Schreier ‐‐‐‐‐Original Message‐‐‐‐‐ From: [email protected] [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, August 24, 2017 7:42 AM To: CLK‐CityClerks Subject: Winnipeg.ca : Comment Good morning! This note is to submit a comment about the reassessing of the City of Winnipeg Boundaries, which is heading for reassessment. My family lives in the Richmond Lakes area of Winnipeg, which is currently a part of the St. Norbert area. Living in this area is wonderful, a small little pocket of community, with parks, walking trails, and a short walk to the area of St. Norbert with the world‐class Farmers' Market, and much more. We love it here! Our current Councillor, Janice Lukes has been OUTSTANDING in putting some love and attention into our area, as we have always suffered from Perimeter‐itis (all projects seemed to happen within the city perimeter). Ms. Lukes has spent a lot of time and money in fixing up our areas. We are all grateful for the construction projects along Pembina Highway, an area that sadly has been over looked and neglected for years and is quite a depressing entrance to our City and should instead be celebrated as a HUGE starting point of one of the the longest roadway system (through to Mexico). Grandmont Park, our little treasure, is getting some love now ‐ upgraded walking paths, opened up parking lot and we are hoping for lights to be installed for the walkers and dog‐walkers' safety. And, what's important, is that Ms. -

Gaboury Préfontaine Perry Architect.E.S

Annexe A Gaboury Préfontaine Perry Architect.e.s Archive Summary Project Number_GAAProject Name Drawing Location File Box College Universitaire de St. Boniface - Student Centre 3 F 1 321? 3 F 3 319 3 F 6 320 3 B 2 322 3 B 2 Selkirk Forensic Unit Tender set Originals 1 A 2 205 3 F 1 3 F 2 3 F 6 3 F 7 Roseau River Bingo Hall 4 B 1 Fort Whyte Nature Co./Arnot Associates 4 B 4 Fort La Bosse K - 4 Virden Elem. School Energy Conservation Competition - P1-upper Forks Tourism Centre 1 K 1 Grids Solar and Wind Direction Demp. graph. Precip. 2 K 8 Maison Taché - D. Dandeneau Mendel Centre - Art Centre and Civic Conservatory Competition 2 J 6 Annexe A Gaboury Préfontaine Perry Architect.e.s Archive Summary Project Number_GAAProject Name Drawing Location File Box Monument de la Paix 2 K 3 Belgium Club 1 D 5 Residence - Landview Housing 3 D 2 Residence - Maurice Gauthier 3 D 6 School Plans - Various - Presentation drawings 3 F 5 Soeurs de Charité - Provincial House 1 I 6 Commercial Office Complex for Raimbault St. Boniface Gaboury Building Locations 2 K 8 E. Gaboury School projects Annexe A Gaboury Préfontaine Perry Architect.e.s Archive Summary Project Number_GAAProject Name Drawing Location File Box Rosser Municipal Office 2 D 3 185 2 D 3 185 185 Hotel La Broquerie 1 F 1 281 1 F 1 281 1 F 1 281 1 F 1 282 1 F 1 282 Psychealth filling 1 K 1 183 2 E 1 HSC 262 265 267 Consultants Invoices to 1992 215 Year Ending 1991 - Consultants 1998 GAA 219 Guy's Archive#1 227 Specifications 230 Spec. -

Manitoba FINAL REPORT INVESTIGATION of the MERITS of MANAGEMENT of RED RIVER SUMMER WATER LEVELS in the CITY of WINNIPEG NOVEMBE

Manitoba CONSERVATION INVESTIGATION OF THE MERITS OF MANAGEMENT OF RED RIVER SUMMER WATER LEVELS IN THE CITY OF WINNIPEG 1-06-Cover_Final_Report.cdr emp\02-31 1-06\ Admin\T s\2002\02-31 KGS FILE NO.:P:\Project FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2003 KONTZAMANIS333 GRAUMANN SMITH MACMILLAN INC. KGS CONSULTING ENGINEERS & PROJECT MANAGERS GROUP INVESTIGATION OF THE MERITS OF MANAGEMENT OF RED RIVER SUMMER WATER LEVELS IN THE CITY OF WINNIPEG FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER, 2003 Investigation of the Merits of Management of November, 2003 Red River Summer Water Levels in the City of Winnipeg – Final Report 02-311-06 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction In October 2002, KGS Group was authorized to proceed with a feasibility study of the merits of summer water level control in the City of Winnipeg. This study was initiated following the emergency operation of the Red River Floodway during the summer of 2002 and a preliminary assessment of summer water control as a part of KGS Group’s November 2001 report, “Flood Protection Studies for Winnipeg” (KGS Group, 2001). The scope of work for this current study was based on a proposal submitted to the Province of Manitoba and to the Project Steering Committee on October 11, 2002. A number of options for summer water level control were considered as a part of the KGS Group study “Flood Protection Studies for Winnipeg” (KGS Group, 2001). The 2001 study concluded that costs to completely eliminate the effects of summer flooding and not raise upstream water levels above the “state-of-nature” would increase the Floodway Expansion costs by over $100 Million. -

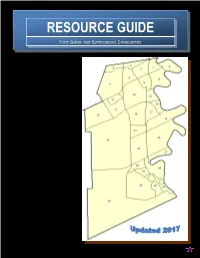

Resource Guide

Page RESOURCE GUIDE FORT GARRY AND SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES 1 POINT ROAD 2 PARKER 3 BEAUMONT 4 WILDWOOD 5 BROCKWOOD 6 BUFFALO 7 LINDEN WOODS 8 CRESCENT PARK 9 MAYBANK 10 CHEVRIER 11 WEST FORT GARRY INDUSTRIAL 12 PEMBINA STRIP 13 LINDEN RIDGE 14 AGASSIZ 15 WHYTE RIDGE 16 WAVERLEY HEIGHTS 17 MONTCALM 18 UNIVERSITY 19 WAVERLEY WEST 20 FORT RICHMOND 21 FAIRFIELD PARK 22 RICHMOND WEST 23 CLOUTHIER DRIVE 24 ST. NORBERT 25 RICHMOND LAKES 26 LA BARRIERE 27 PARC LA SALLE 28 TRAPPISTES 29 TURNBULL DRIVE 30 PERAULT Updated Fall 2017 Resource Guide: Fort Garry and surrounding communities Page 2 The resource guide was originally developed and produced for the Fort Garry Community Network by a Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (WRHA) Community Development Volunteer Assistant. Network partners have continued to update the guide to share information. FORT GARRY COMMUNITY NETWORK WHO WE ARE The Network is comprised of child and youth servicing organizations, family support agencies, senior services and faith communities. Government and education sectors are also represented. OUR MISSION “WORKING COLLABORATIVELY TO PROMOTE THE HEALTHY DEVELOPMENT OF CHILDREN, YOUTH, SENIORS, AND FAMILIES.” MEMBERSHIP The Network meets the third Thursday in the months of September, November, January, March and May from 9:00 to 11:00 a.m. at the Southlands Community Church (85 Keslar Rd.) in Richmond West. There are sub-committees of the Network that meet regularly. For more information visit their website at: www.fortgarrycommunitynetwork.ca updated Fall 2017 Resource Guide: -

Habitat Means Home

(!")4!4-%!.3(/-%-!--!,3 (!")4!4-%!.3(/-%-!--!,3 FRONT FRONT -!--!,3 REAR REAR 2%$!.$'2%9315)22%,3 4HEREAREMANYKINDSOFSQUIRRELSINTHEFOREST2EDANDGREYSQUIRRELSARETHE ONESYOUWILLLIKELYSEE&LYINGSQUIRRELSONLYCOMEOUTATNIGHT2EDSQUIR 2!##//. RELSARESMALLERTHANGREYSQUIRRELSANDAREREDWITHAWHITEBELLY4HEYOFTEN 9OUCANALWAYSRECOGNIZEARACCOONBYTHEBLACKMASKITWEARSANDTHE CHATTERATYOUFORBEINGINTHEIRTERRITORY'REYSQUIRRELSAREBIGGERANDGREY BLACKRINGSONITSTAIL)TLOOKSLIKEAREALLYBIGGREYHOUSECAT2ACCOONSARE COLOUREDWITHAWHITEBELLYANDBUSHYTAIL"OTHAREHERBIVORES,OOKFORARED OMNIVORESnTHEYEATPLANTSLIKEBERRIESANDANIMALSLIKECRAYFISH TURTLES SQUIRRELNESTOFSTICKSANDLEAVESINTHETREES!NOTHERSIGNOFASQUIRRELISA MICEANDFROGS4HEYARENOCTURNALnTHATMEANSTHEYCOMEOUTATNIGHT4HEY PILEOFSEEDORNUTSHELLS SLEEPINTREESDURINGTHEDAY2IVERBOTTOMFORESTISTHEIRFAVOURITEPLACETO LIVE 2IVERS7EST!NIMALSOFTHE2IVERBOTTOM&OREST 0AGE -!--!,3 -!--!,3 FRONT -!--!,3 REAR 7()4%4!),%$$%%2 7HITE TAILEDDEERARELARGEHERBIVORES9OUCANSEETHEMEATINGGRASSATTHE EDGEOFTHEFOREST4HEYARERED BROWNINSUMMERANDGREY BROWNINWINTER 3+5.+ -ALEDEERGROWANTLERSOVERTHESUMMERTHATFALLOFFINTHEWINTER"ABYDEER %VERYONEKNOWSTHESKUNKnBLACKFURWITHAWHITESTRIPEDOWNITSBACKAND ARETHESIZEOFYOU4HEIRMOMHIDESTHEMINTHEGRASSDURINGTHEDAYnIFYOU BIGBUSHYTAIL)FYOUSEEASKUNKYOUBETTERGETOUTOFITSWAYnITSPRAYSA FINDONEJUSTLEAVEITALONE BECAUSEMOMISCLOSEBYBUTHIDING4HEBEST FOULPERFUMEIFSCARED3KUNKSAREOMNIVORES4HEYLIKEBIRDSEGGS INSECTS TIMETOSEEDEERISEARLYMORNINGANDSUNDOWN,OOKFORTHEIRTRACKSINMUD MICE PLANTSANDEVENCARRIONnDEADANIMALS ORSNOWALONGTRAILS 2IVERS7EST!NIMALSOFTHE2IVERBOTTOM&OREST -

A Mandarin Version

PLAZA E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Fort Garry Wildwood 1 Osborne Village 1 Downtown BISHOP GRANDIN PEMBINA 2 2 Waverley West Whyte Ridge Fort Garry Bridge Fort Whyte Alive Assiniboine Park and the Zoo BISHOP GRANDIN GREENWAY Charleswood 3 3 GLENGARRY St.Vital Park Henteleff Park * 2015 St.Vital Centre Seine River Greenway WEDGWOOD CHANCELLOR * ? Agassiz THATCHER 4 4 D’ARCCY $ AGASSIZ UNIVERSITY CR $ 5 5 THATCHER THATCHER Park&Ride 6 6 SOUTHPARK Southwood Lands 7 R 7 MARKHAM MARKHAM E 2235 D R I SNOW V DARTMOUTH 8 8 PEMBINA E SIFTON R SIDNEY SMITH SIDNEY St.Andrew’s Victoria General Day Care Hospital New Garden Path Geology DYSART 9 9 BIKE VALET Acadia By I17 St.Paul’s St.John’s Agassiz Dr Q4 Allegheny Dr I15 Indoor Chem Soccer April St Q13 Gym Math Pan Am DYSART Aurora St P14 Investors Group Track Field Physics Science Avila Av Q15 New Bike Lane Bike New Law Bairdmore Bv N G13 RALPH CAMPBELL Zoology Theatre UNIVERSITY CR Pharmacy Psych Botany Bairdmore Bv S C21 Microbiology Human 10 Ecology Planetarium Baldry By M16 10 BISON Gym Parkade Art Microbiology Education CURRY Bike Corral Botany Baylor Av G18 ASC Bike Repair Bayridge Av I13 Nursing University Centre SAUNDERSON Bishop Grandin Bv N2 CHANCELLOR MATHESON Admin Bishop Grandin Green- Q2 Continuing Education $ way Arts Bison Dr I10 Arch Research Lands RH WAY RH Pool Planning Gym Architecture GILSON Briar Cliff By K17 Engineering Kinesiology Bridgeport Pl J20 11 Sociology 11 Active Living Geography Bromley Pl F21 TECHNOLOGY ? Centre Music H19 RESEARCH CAST Bryn Mawr Rd INNOVATION DAFOE W DAFOE Burgess Av J22 ALUMNI Burnham Rd E24 Animal Sci. -

Appendix D: Ward Detail Report, 2020 Report on Parks and Open Space Assets

Appendix D: Ward Detail Report, 2020 Report on Parks and Open Space Assets Asset data as of September 30, 2020 Table of Contents Electoral Ward Page Charleswood ‐ Tuxedo ‐ Westwood 3 Daniel McIntyre 28 Elmwood ‐ East Kildonan 40 Fort Rouge ‐ Fort Garry 54 Mynarski 72 North Kildonan 90 Old Kildonan 109 Point Douglas 128 River Heights ‐ Fort Garry 146 St. Boniface 163 St. James 190 St. Norbert ‐ Seine River 214 St. Vital 232 Transcona 253 Waverley West 279 Outside City Limit 292 Electoral Ward: Charleswood ‐ Tuxedo ‐ Westwood Parks and Open Space Listed by Name, Location and Size AREA NAME OF PARK OR OPEN SPACE LOCATION/ADDRESS (HA) Aldershot Strip 5 Aldershot Blvd 0.34 Assiniboine Forest 950 Shaftesbury Blvd 292.20 Assiniboine Park 6 Locomotive Dr 163.31 Assiniboine Woods‐Great Elm Buffer N side Roblin Blvd between William Marshall Wy & 0.30 Lannoo Dr Assiniboine Woods‐Sanders Buffer NW Roblin Blvd & William Marshall Wy 0.11 Bannatyne Grove 5605 Roblin Blvd 0.34 Bard Place Park N of Bard Place E of Shaftesbury Blvd 0.78 Barker Buffer NE Roblin Blvd & Barker Blvd 0.04 Beauchemin Park 5921 Southboine Dr 3.81 Beaumont School Park E side Civic St, S of Betsworth Ave 1.91 Beaverdam Creek 75 Carlotta Cres 1.12 Beaverdam Creek Greenway Between Buckle Dr, Carlotta Cres & Carlos Ln 0.25 Beaverdam Creek Window 544 Berkley St 0.11 Bedson Park 460 Bedson St 1.08 Benjaminson Park 3432 Assiniboine Ave 0.14 Berkley Square 635 Berkley St 0.27 Birkenhead Strip 15 Devonport Blvd 0.49 Bramble Drive Park 29 Bramble Dr 0.31 Browning Boulevard Extension 254