This Article Is Forthcoming in Anglo-Saxon Predecessors and Precedents (Ed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.Net

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.net Edward the Martyr (Old English: Eadweard; c. 962 – 18 March 978) was King of England from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar the Peaceful but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his much younger half-brother Æthelred the Unready, recognized as a legitimate son of Edgar. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan and Oswald of Worcester. The great nobles of the kingdom, ealdormen Ælfhere and Æthelwine, quarrelled, and civil war almost broke out. In the so-called anti-monastic reaction, the nobles took advantage of Edward's weakness to dispossess the Benedictine reformed monasteries of lands and other properties that King Edgar had granted to them. Edward's short reign was brought to an end by his murder at Corfe Castle in 978 in circumstances that are not altogether clear. His body was reburied with great ceremony at Shaftesbury Abbey early in 979. In 1001 Edward's remains were moved to a more prominent place in the abbey, probably with the blessing of his half-brother King Æthelred. Edward was already reckoned a saint by this time. A number of lives of Edward were written in the centuries following his death in which he was portrayed as a martyr, generally seen as a victim of the Queen Dowager Ælfthryth, mother of Æthelred. -

Ss. Peter & Paul

3rd Sunday After Pentecost Tone 2 June 17, 2018 SS. PETER & PAUL Lorain, OH | www.OrthodoxLorain.org | (440) 277-6266 Rev. Joseph McCartney, Rector Cell (440) 668 - 2209 ~ Email: [email protected] ~ Home (440) 654-2831 Gospel Reading ~ Matthew 6:22-33 Epistle Reading ~ Romans 5:1-10 All Saints of Britain and Ireland This Week at a Glance Gospel Meditation Wed, June 20th In today’s Gospel, Jesus says that the light of the body is the eye. If 6:00 pm - Akathist to Ss Peter the eye is light, so the body will be light. But if the eye is dark, so the body & Paul will be dark. By 'eye' is meant the soul, for the eye is the window of the soul. In these words Our Lord says that we are not to blame our bodies for our Sat, June 23rd sins. Our bodies are the servants of our souls. If our souls are corrupted, then 6:00 pm - Great Vespers so also will be our bodies. On the other hand, if our souls are clean, then our bodies will also be clean. It is not our bodies which control our lives, or even Sun, June 24th our minds, but our souls. And it is our souls that we are called on to cleanse, 9:00 pm - 3rd & 6th Hours cultivate and refine first of all. It is the spiritual which has primacy in our 9:30 am - Divine Liturgy lives. Once our souls are clean, then our minds and our bodies will also be cleaned. Neither can we serve two Masters, the master of the material world Parish Council and the master of the spiritual world. -

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti Eethelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti EEthelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi Nicola Jane Robertson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, Centre for Medieval Studies, September 2003 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Mary Swan and Professor Ian Wood for their guidance and support throughout the course of this project. Professor Wood's good-natured advice and perceptive comments have helped guide me over the past four years. Dr Swan's counsel and encouragement above and beyond the call of duty have kept me going, especially in these last, most difficult stages. I would also like to thank Dr William Flynn, for all his help with my Latin and useful commentary, even though he was not officially obliged to offer it. My advising tutor Professor Joyce Hill also played an important part in the completion of this work. I should extend my gratitude to Alison Martin, for a constant supply of stationery and kind words. I am also grateful for the assistance of the staff of the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. I would also like to thank all the students of the Centre for Medieval Studies, past and present, who have always offered a friendly and receptive environment for the exchange of ideas and assorted cakes. -

Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr From OrthodoxWiki The holy and right-believing King Edward the Martyr (c. 962 – March 18, 978/979) succeeded his father Edgar of England as King of England in 975, but was murdered after a reign of only a few years. As the murder was attributed to "irreligious" opponents, whereas Edward himself was considered a good Christian, he was glorified as Saint Edward the Martyr in 1001; he may also be considered a passion-bearer. His feast day is celebrated on March 18, the uncovering of his relics is commemorated on February 13, and the elevation of his relics on June 20. The translation of his relics is commemorated on September 3. St. Edward the Martyr Contents 1 Motive and details of his murder 2 History of his relics 3 See also 4 Source 5 External links Motive and details of his murder Edward's accession to the throne was contested by a party headed by his stepmother, Queen Elfrida, who wished her son, Ethelred the Unready, to become king instead. However, Edward's claim had more support—including that of St. Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury—and was confirmed by the Witan. King Edward "was a young man of great devotion and excellent conduct. He was completely Orthodox, good and of holy life. Moreover, he loved God and the Church above all things. He was generous to the poor, a haven to the good, a champion of the Faith of Christ, a vessel full of every virtuous grace." On King Edward's accession to the throne a great famine was raging through the land and violent attacks were stirred up against monasteries by prominent noblemen who coveted the lands that his father King Edgar had endowed to them. -

THE FIRST AUTHORIZED ISSUE of EDWARD the CONFESSOR.L ~C R

THE FIRST AUTHORIZED ISSUE OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR.l By H. ALEXANDER PARSONS. c r'" HERE are reasons for thinking that there is still some doubt t! regarding the first issue of coins authorized for currency in ~r_ . this country after Edward the Confessor was acclaimed king on the death of Harthacnut in A.D. 1042. The first scientific arrangement of the types of coins of this king was that of Hildebrand when he catalogued the Anglo-Saxon coins in the Royal Collection in Stockholm. This arrangement dates back to the year 1846, and no drastic alteration of it was made on the publication of a second edition of the catalogue in 1881, notwithstanding the fact, convincingly set forth by Dr. Head, in his remarks on the Chancton hoard of 1865,2 that Hildebrand's type A variety c must be placed as a substantive type, struck towards the end instead of at the beginning of the reign. The only substantial alteration in Hildebrand's second edition was the inclusion of two important varieties called by him, in the second edition, type C, varieties c and d. • In the British Museum Catalogue of English Coins, Anglo-Saxon Series, vol. ii, 1893, the initial issue of the reign is the same as that given the premier place by Hildebrand; but in the latest treatise on the coins of Edward the Confessor, namely, that by Major P. W. P. Carlyon-Britton,3 this is displaced by some coins called by the author, the "Harthacnut" Type. This is represented III Hildebrand's second edition as Type C, varieties c and d. -

Lives of the British Saints

LIVES OF THE BRITISH SAINTS Vladimir Moss Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2009 1. SAINTS ACCA AND ALCMUND, BISHOPS OF HEXHAM ......................5 2. SAINT ADRIAN, ABBOT OF CANTERBURY...............................................8 3. SAINT ADRIAN, HIEROMARTYR BISHOP OF MAY and those with him ....................................................................................................................................9 4. SAINT AIDAN, BISHOP OF LINDISFARNE...............................................11 5. SAINT ALBAN, PROTOMARTYR OF BRITAIN.........................................16 6. SAINT ALCMUND, MARTYR-KING OF NORTHUMBRIA ....................20 7. SAINT ALDHELM, BISHOP OF SHERBORNE...........................................21 8. SAINT ALFRED, MARTYR-PRINCE OF ENGLAND ................................27 9. SAINT ALPHEGE, HIEROMARTYR ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY ..................................................................................................................................30 10. SAINT ALPHEGE “THE BALD”, BISHOP OF WINCHESTER...............41 11. SAINT ASAPH, BISHOP OF ST. ASAPH’S ................................................42 12. SAINTS AUGUSTINE, LAURENCE, MELLITUS, JUSTUS, HONORIUS AND DEUSDEDIT, ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ..............................43 13. SAINTS BALDRED AND BALDRED, MONKS OF BASS ROCK ...........54 14. SAINT BATHILD, QUEEN OF FRANCE....................................................55 15. SAINT BEDE “THE VENERABLE” OF JARROW .....................................57 16. SAINT BENIGNUS (BEONNA) -

A Handlist of Anglo-‐Latin Hagiography Through the Early Twelfth Century

A HANDLIST OF ANGLO-LATIN HAGIOGRAPHY THROUGH THE EARLY TWELFTH CENTURY (FROM THEODORE OF TARSUS TO WILLIAM OF MALMESBURY) Thomas N. Hall The following list originated as a handout developed for a seminar on Anglo-Saxon Hagiography taught at the University of Notre Dame in Spring 2010. Its aim is to supply a provisional inventory, for classroom purposes, of all major known works of Latin hagiography (primarily saints’ Lives and miracle collections but also select sermons, hymns, and other texts that have saints as their subjects) written in Britain or by native British authors or by authors writing anywhere about British saints, from the time of Archbishop Theodore (602–690) to William of Malmesbury (ca. 1090–ca. 1143). The objective here is not to provide exhaustive bibliographical coverage for every single text and author but to offer a basic orientation to the corpus with the hope of stimulating further work. In most cases, only the best or most recent editions and translations are cited, along with the most important secondary scholarship as it has come to my attention, but scholarship published after 2010 is not included. Also not included are the Lives of eminent churchmen who were never canonized, e.g. Vita Gundulfi, ed. R. M. Thomson (Toronto, 1977). Fuller bibliography for many of these authors and texts can be found in BHL; Compendium Auctorum Latinorum Medii Aevi (500–1500), ed. Michael Lapidge, Gian Carlo Garfagnini, and Claudio Leonardi (Florence, 2003– ); Richard Sharpe’s Handlist of the Latin Writers of Great Britain and Ireland before 1540 (Turnhout, 1997); and in the case of Alcuin, Marie- Hélène Jullien and Françoise Perelman, Clavis Scriptorum Latinorum Medii Aevi. -

Who Wrote the Nun's Life of Edward? 1

77 Who Wrote the Nun's Life of Edward? 1 Jane Bliss University ofOxford This article examines the identity of the Nun of Barking, aut~or of an Anglo Norman Life of Edward the Confessor; and addresses three questions. The flrst is about the Nun's audience; the poem's destination is a vital element in discussion of the author's identity, and of the quality of her authorship. Next, I examine the available evidence for sources other than Aelred's Vita; the Nun's work has sometimes been regarded as a mere copy: 'a translation from start to flnish'. 3 My title focuses on 'writing' in the sense of 'authorship', because the Nun adapts her material so extensively that she can claim to be the author, not merely the translator, of her Edward. Lastly, to establish whether the Nun was identical with Clemence of Barking, author of the Life of Saint Catherine (of Alexandria),' I analyse both poems. My study draws upon a body of recent scholarship on women's writing, and on AnglO-Norman language and literatureS The Nun's poem is a key text for a recent study of early mysticism;' this aspect of her work has therefore been discussed elsewhere, as has her pioneering use of the term 'fln' amor', and the enhanced role of Edith, Edward's queen.' Earlier scholars' neglect of the poem may be because some perceived it as a slavish translation, or because it suffered in comparison with the freer (later) version by Matthew Paris' Laurent thinks Matthew wanted to suppress it,' but there is no evidence that Matthew did any such thing: the Nun's work survives in three manuscripts, and a fragment. -

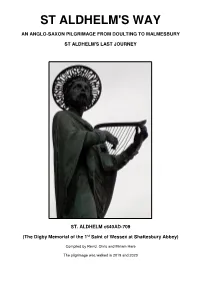

St Aldhelm's Way

ST ALDHELM'S WAY AN ANGLO-SAXON PILGRIMAGE FROM DOULTING TO MALMESBURY ST ALDHELM'S LAST JOURNEY ST. ALDHELM c640AD-709 (The Digby Memorial of the 1st Saint of Wessex at Shaftesbury Abbey) Compiled by Rev'd. Chris and Miriam Hare The pilgrimage was walked in 2019 and 2020 AN INTRODUCTION TO CHRISTIANITY AND TO THE ANGLO SAXONS Christianity was first practised in Britain towards the end of the second century, and was mostly based in towns where paganism was also practised. Germanic tribes started to settle in Romano-Celtic Britain in the middle of the fifth century. The Angles came from modern Denmark, the Saxons from modern northern Germany and the Jutes from the coast of Germany and Holland. Saxons conquered South West England in the sixth century and formed the kingdom of the West Saxns. They were pagans and Christianity had nearly died out. In 596AD Pope Gregory sent a mission led by Augustine to “ preach the word of God to the English race". They arrived in Thanet in Kent in 597AD. King Aethelberht of Kent's wife was already a Christian, and he was converted and then baptised. Soon after 10,000 converts were baptised on Christmas Day in 597AD, and many others followed. Old churches were restored and new ones were built. Roman Christianity had come to England. Then Pope Gregory’s successor, Honorius, sent another mission with Bishop Birinus to England in 634AD again to preach the gospel. He landed in Wessex, baptised the king of the West Saxons, Cynegils, and then many of the population of Wessex. -

The Character of the Treacherous Woman in the Passiones of Early Medieval English Royal Martyrs

2020 VII The Character of the Treacherous Woman in the Passiones of Early Medieval English Royal Martyrs Matthew Firth Article: The Character of the Treacherous Woman in the Passiones of Early Medieval English Royal Martyrs The Character of the Treacherous Woman in the Passiones of Early Medieval English Royal Martyrs Matthew Firth FLINDERS UNIVERSITY Abstract: Early medieval England is well-known for its assortment of royal saints; figures who, though drawn from nearly five centuries of pre-Conquest Christianity, are often best known from eleventh-century hagiography. Common among these narratives is the figure of the “wicked queen”–a woman whose exercise of political power provides the impetus for the martyrdom of the royal saint. Flatly drawn and lacking in complex motivation, the treacherous woman of English hagiography is a trope, a didactic exemplar tailored to eleventh-century English audiences, and a caution of the dangers of female agency. Here biblical archetypes, clerical scholarship, and an inherent social misogyny unite in a common literary framework. Yet it is also true that each of these “wicked queens” has a unique transmission history that displays a complicated progression of the motif within a living narrative. This article examines the role of the treacherous woman as a narrative device in three royal hagiographies: Passio S. Æthelberhti, Vita et miracula S. Kenelmi, and Passio S. Eadwardi regis et martyris. In so doing, it explores the authorial motives and social influences that informed the composition of these figures, arguing that each is formed of a convergence of the historical and regional contexts of the saints’ cults with the political concerns and ecclesiastical anxieties of the tenth and eleventh centuries. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Constructing Gender and Locality in Late Medieval England The Lives of Anglo-Saxon and British Female Saints in the South English Legendaries Kanno, Mami Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Constructing Gender and Locality in Late Medieval England: The Lives of Anglo-Saxon and British Female Saints in the South English Legendaries Mami Kanno Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Faculty of Arts and Humanities King’s College London 2016 Abstract This thesis examines the construction of gender and locality in late medieval England through the lives of Anglo-Saxon and British female saints in the South English Legendaries (SELS). -

![Two Anglo-Saxon Notes: [1] an Enigmatic Penny of Edward the Martyr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2693/two-anglo-saxon-notes-1-an-enigmatic-penny-of-edward-the-martyr-3692693.webp)

Two Anglo-Saxon Notes: [1] an Enigmatic Penny of Edward the Martyr

TWO ANGLO-SAXON NOTES By R. H. M. DOLLEY AN ENIGMATIC PENNY OF EDWARD THE MARTYR THE purpose of this note is not to claim that there was a late Saxon mint at Louth in Lincolnshire—the evidence is quite insufficient—but simply to draw attention to a broken and hitherto neglected coin from the 1914 Pemberton's Parlour hoard from Chester. The fragment in question (below) appears as no. 42 in Sir George Hill's masterly pub- lication of the hoard, and is now in the British Museum.1 It is hoped that the enlarged photographs will enable the reader to judge for him- self the essential accuracy of Hill's readings which were as follows: Obv. +[ JRE+AHC Rev. [ ]ALDN~OLVN[ ] The dots that appear beneath the initial cross on the obverse and the second N of the reverse legend were to indicate that Hill himself con- sidered his interpretation of the letter doubtful. As regards the initial cross there can be little doubt but that it was correctly read, but in the case of the second N on the reverse examination of the actual coin confirms that all that can be stated with any confidence is that it is a letter which has for its first element an upright stroke. As far as the numismatic alphabet of the tenth century is concerned, the letter could as well be a B, C, D, E, F, G, H, L, M, P, R., or P. Although not one letter of the king's name has been preserved, Hill listed the coin under Edward the Martyr, adding a note that the identification of the king was "not certain".