Steelmaking: History and the Modern Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel

ACADEMIC PULSE Higher-Quality Electric-Arc Furnace Steel teelmakers have traditionally viewed Research Continues to Improve the electric arc furnaces (EAFs) as unsuitable Quality of Steel for producing steel with the highest- Even with continued improvements to the Squality surface finish because the process design of steelmaking processes, the steelmaking uses recycled steel instead of fresh iron. With over research community has focused their attention 100 years of processing improvements, however, on the fundamental materials used in steelmaking EAFs have become an efficient and reliable in order to improve the quality of steel. In my lab steelmaking alternative to integrated steelmaking. In at Carnegie Mellon University, we have several fact, steel produced in a modern-day EAF is often research projects that deal with controlling the DR. P. BILLCHRIS MAYER PISTORIUS indistinguishable from what is produced with the impurity concentration and chemical quality of POSCOManaging Professor Editorof Materials integrated blast-furnace/oxygen-steelmaking route. steel produced in EAFs. Science412-306-4350 and Engineering [email protected] Mellon University Improvements in design, coupled with research For example, we recently used mathematical developments in metallurgy, mean high-quality steel modeling to explore ways to control produced quickly and energy-efficiently. phosphorus. Careful regulation of temperature, slag and stirring are needed to produce low- Not Your (Great-) Grandparent’s EAF phosphorus steel. We analyzed data from Especially since the mid-1990s, there have been operating furnaces and found that, in many significant improvements in the design of EAFs, cases, the phosphorus removal reaction could which allow for better-functioning burners and a proceed further. -

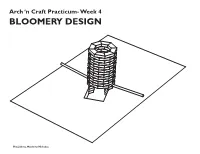

Bloomery Design

Arch ‘n Craft Practicum- Week 4 BLOOMERY DESIGN Hiu, Julieta, Matthew, Nicholas 7 3/4" The Stack: 3 3/4" In our ideal model we would use refractory bricks, either rectangular bricks or curved bricks which would help us make a circular 1'-8" stack. The stack would be around 3 feet tall with a 1 foot diameter for the inner wall of the stack. There will be openings about 3 brick lengths up(6-9 inches) from the ground on 1'-0" opposite ends of the stack. Attached to these openings will be our tuyeres which in turn will connect to our air sources. Building a circular stack would be beneficial to the type of air distribution we want to create within our furnace; using two angled tuyeres we would like air to move clockwise and counterclock- Bloomery Plan wise. We would like to line the inside of the stack with clay to provide further insulation. Refractory bricks would be an ideal material to use because the minerals they are com- posed of do not change chemically when 1'-0" exposed to high heat, some examples of these materials are aluminum, manganese, silica and zirconium. Other comments: 3'-0" Although we have opted to use refractory bricks, which would be practical for our intended purpose, we briefly considered using Vycor glass which can withstand high tem- peratures of up to 900 degrees celsius or approximately 1652 degrees Fahrenheit, which Tuyere height: Pitched -10from horizontal 7" would be enough for our purposes. Bloomery Section Ore/ Charcoal: Our group has decided to use Magnetite ore along with charcoal for the smelt. -

Distortion in Case Carburized Components- the Steelmakers View

Heat Treating: Proceedings of the 18th Conference Copyright © 1999 ASM International® Ronald A. Wallis, Harry W. Walton, editors, p 5-11 All rights reserved. DOI: 10.1361/cp1998ht005 www.asminternational.org Distortion in Case Carburized Components The Steel makers View M. Cristinacce British Steel Engineering Steels Rotherham, United Kingdom 1. Abstract NVH (noise, vibration and harshness) is becoming of increasing importance in the automotive industry. The control Distortion of components during heat treatment has a of distortion to give correct mating of rotating components significant effect upon final component costs. The factors such as gears and shafts has a major influence upon NVH which influence distortion behaviour occur during the performance. machining and heat treatment processes and are therefore Most of the examples given in this paper are automotive outside the control of the steelmaker. One important factor transmission components which are carburised. which is under the control of the steelmaker is hardenability A wide variety of factors influence distortion behaviour Consistent hardenability performance can have a significant and can be broadly summarised as follows: effect in reducing the variability in distortion. In a number of Component shape. instances it has been shown that the macrostructure and Steel type. as-cast shape of the steel can also influence distortion. Other Microstructure and residual stresses prior to heat downstream processing effects such as forging may also be treatment. influential in these circumstances. Reheating and carburising conditions. This paper gives examples of some of the experiences of Stacking and support in furnace. British Steel Engineering Steels with customers and end users, Quenching - Medium, temperature, flow, jigging, etc. -

Decarbonising Steelmaking: Technology Options and Regional Pathways

Decarbonising steelmaking: technology options and regional pathways Huw McKay Chief Economist Ben Ellis Head of Marketing Strategy and Technical Marketing Wenjun Bao Manager Steel and Nonferrous Analysis Lee Levkowitz Manager Energy and Technology Research 11 November 2020 Disclaimer Forward-looking statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements, including statements regarding: trends in commodity prices and currency exchange rates; demand for commodities; production forecasts; plans, strategies and objectives of management; closure or divestment of certain assets, operations or facilities (including associated costs); anticipated production or construction commencement dates; capital costs and scheduling; operating costs and shortages of materials and skilled employees; anticipated productive lives of projects, mines and facilities; provisions and contingent liabilities; and tax and regulatory developments. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of terminology, including, but not limited to, ‘intend’, ‘aim’, ‘project’, ‘anticipate’, ‘estimate’, ‘plan’, ‘believe’, ‘expect’, ‘may’, ‘should’, ‘will’, ‘would’, ‘continue’, ‘annualised’ or similar words. These statements discuss future expectations concerning the results of assets or financial conditions, or provide other forward-looking information. These forward-looking statements are based on the information available as at the date of this release and are not guarantees or predictions of future performance, and involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control, and which may cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements contained in this release. BHP cautions against reliance on any forward-looking statements or guidance, particularly in light of the current economic climate and the significant volatility, uncertainty and disruption arising in connection with COVID-19. -

Technical Progress in Steelmaking and Casting for Special Bar and Wire Steel at Muroran Works

NIPPON STEEL TECHNICAL REPORT No. 104 AUGUST 2013 Technology UDC 669 . 184 . 244 . 66 : 669 . 14 - 422 Technical Progress in Steelmaking and Casting for Special Bar and Wire Steel at Muroran Works Masato KOBAYASHI* Kohichi ISOBE Masayuki ARAI Abstract Muroran Works, Nippon Steel Corporation manufactures special bars and wire rods mainly for automotive parts. In steelmaking plant, many technologies have been developed to manufacture high grade special steel and to suit the users’ various needs, e.g. multi-refin- ing converter (MURC), secondary steelmaking and casting to improve steel cleanliness, and near net casting and compact high reduction process (NCR). Authors describe recent ad- vances and prospects in steelmaking and casting technologies for manufacturing special steel in Muroran Works. 1. Introduction 2. Outline of Muroran Works Founded in 1909, Nippon Steel Corporation’s Muroran Works In 1994, the ironmaking department of Muroran was separated (hereinafter simply called “Muroran”) is the only integrated iron and from Nippon Steel Muroran Works, and the former was used to es- steel works in Hokkaido and manufactures special steels for bars tablish 80% of a joint venture with MSR, known as Hokkai Iron & and wire rods. Nearly 90% of the products of Muroran are special Coke Corporation. Since then, Hokkai Iron & Coke has been the steels, which are used mainly for critical automotive components supplier of hot metal to Muroran᾽s basic oxygen furnace (converter) (the engine, driving system, and undercarriage) and various parts of and electric furnace. The steel source used at Muroran is converter industrial machinery and construction equipment (Fig. 1). Since 1994, Muroran has also been manufacturing bars and wire rods in cooperation with Mitsubishi Steel Muroran, Inc. -

Steelmaking by Electric Arc Furnaces Cleaner, More Efficient

EVRAZ Canadian Steel: Low Carbon Footprint November 2016 Electric Arc Furnaces (EAFs) with metal scrap: cleaner, more efficient • EVRAZ Regina utilizes two Electricity Steelmaking EAFs to make up to 1.1 Generation million tons of steel per Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions year kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% • Over 91% of steelmaking -64% -81% 2,081 in China is from Blast 4,624 764 Oxygen Furnaces (BOFs), which use iron ore, coking coal, and other inputs • For every one ton of steel scrap made into new steel, over 1,400kg of iron ore, 1,647 740kg of coal, and 120kg 441 147 of limestone are saved Overseas input shipping to China Blast EAF Blast EAF China Canada Furance Furnace Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. Scrap statistics: Worldsteel. Electricity Generation: IEA 2011 2 EVRAZ cleaner EAFs, Canada’s power generation outpace others Emissions from Steelmaking emissions and energy use energy generation Energy used CO2 emissions CO2 emissions kg / ton of steel kWh / ton of steel grams / kWh -79% -64% 2,081 4,624 -81% 764 1,526 3,419 2,327 476 470 929 1,647 441 147 China Germany Turkey EVRAZ Blast GermanyTurkey EAF China Turkey Germany Canada - BOF Canada Furnace - EAF - China Overseas shipping of inputs Sources: BOF percentage: Worldsteel. Shipping emissions: National Technical University of Athens, from China to BC, Europe to Houston. Steelmaking: Midrex – Blast Furnace assuming 11% Scrap, EAF Use of 100% scrap. -

The Future of Steelmaking– Howeuropean the MANAGEMENT SUMMARY

05.2020 The future of steelmaking – How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality MANAGEMENT SUMMARY The future of steelmaking / How the European steel industry can achieve carbon neutrality The European steelmaking industry emits 4% of the EU's total CO2 emissions. It is under growing public, economic and regulatory pressure to become carbon neutral by 2050, in line with EU targets. About 60% of European steel is produced via the so-called primary route, an efficient but highly carbon-intensive production method. The industry already uses carbon mitigation techniques, but these are insufficient to significantly reduce or eliminate carbon emissions. The development and implementation of new technologies is underway. With limited investment cycles left until the 2050 deadline, the European steelmaking industry must decide on which new technology to invest in within the next 5-10 years. We assess the most promising emerging technologies in this report. They fall into two main categories: carbon capture, use and/or storage (CCUS), and alternative reduction of iron ore. CCUS processes can be readily integrated into existing steel plants, but cannot alone achieve carbon neutrality. If biomass is used in place of fossil fuels in the steelmaking process, CCUS can result in a negative carbon balance. Alternative reduction technologies include hydrogen-based direct reduction processes and electrolytic reduction methods. Most are not well developed and require huge amounts of green energy, but they hold the promise of carbon-neutral steelmaking. One alternative reduction process, H2-based shaft furnace direct reduction, offers particular promise due to its emissions-reduction potential and state of readiness. -

AISI | Electric Arc Furnace Steelmaking

http://www.steel.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Articles3&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=12308 Home Steelworks Home Electric Arc Furnace Steelmaking By Jeremy A. T. Jones, Nupro Corporation SIGN UP to receive AISI's FREE e-news! Read the latest. Email: Name: Join Courtesy of Mannesmann Demag Corp. FURNACE OPERATIONS The electric arc furnace operates as a batch melting process producing batches of molten steel known "heats". The electric arc furnace operating cycle is called the tap-to-tap cycle and is made up of the following operations: Furnace charging Melting Refining De-slagging Tapping Furnace turn-around Modern operations aim for a tap-to-tap time of less than 60 minutes. Some twin shell furnace operations are achieving tap-to-tap times of 35 to 40 minutes. 10/3/2008 9:36 AM http://www.steel.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Articles3&TEMPLATE=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=12308 Furnace Charging The first step in the production of any heat is to select the grade of steel to be made. Usually a schedule is developed prior to each production shift. Thus the melter will know in advance the schedule for his shift. The scrap yard operator will prepare buckets of scrap according to the needs of the melter. Preparation of the charge bucket is an important operation, not only to ensure proper melt-in chemistry but also to ensure good melting conditions. The scrap must be layered in the bucket according to size and density to promote the rapid formation of a liquid pool of steel in the hearth while providing protection for the sidewalls and roof from electric arc radiation. -

Enghandbook.Pdf

785.392.3017 FAX 785.392.2845 Box 232, Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expy Minneapolis, KS 67467 ENGINEERING HANDBOOK TECHNICAL INFORMATION STEELMAKING Basic descriptions of making carbon, alloy, stainless, and tool steel p. 4. METALS & ALLOYS Carbon grades, types, and numbering systems; glossary p. 13. Identification factors and composition standards p. 27. CHEMICAL CONTENT This document and the information contained herein is not Quenching, hardening, and other thermal modifications p. 30. HEAT TREATMENT a design standard, design guide or otherwise, but is here TESTING THE HARDNESS OF METALS Types and comparisons; glossary p. 34. solely for the convenience of our customers. For more Comparisons of ductility, stresses; glossary p.41. design assistance MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF METAL contact our plant or consult the Machinery G.L. Huyett’s distinct capabilities; glossary p. 53. Handbook, published MANUFACTURING PROCESSES by Industrial Press Inc., New York. COATING, PLATING & THE COLORING OF METALS Finishes p. 81. CONVERSION CHARTS Imperial and metric p. 84. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Steelmaking 4 Metals and Alloys 13 Designations for Chemical Content 27 Designations for Heat Treatment 30 Testing the Hardness of Metals 34 Mechanical Properties of Metal 41 Manufacturing Processes 53 Manufacturing Glossary 57 Conversion Coating, Plating, and the Coloring of Metals 81 Conversion Charts 84 Links and Related Sites 89 Index 90 Box 232 • Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expressway • Minneapolis, Kansas 67467 785-392-3017 • Fax 785-392-2845 • [email protected] • www.huyett.com INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was created based on research and experience of Huyett staff. Invaluable technical information, including statistical data contained in the tables, is from the 26th Edition Machinery Handbook, copyrighted and published in 2000 by Industrial Press, Inc. -

Ironworks and Iron Monuments Forges Et

IRONWORKS AND IRON MONUMENTS FORGES ET MONUMENTS EN FER I( ICCROM i ~ IRONWORKS AND IRON MONUMENTS study, conservation and adaptive use etude, conservation et reutilisation de FORGES ET MONUMENTS EN FER Symposium lronbridge, 23-25 • X •1984 ICCROM rome 1985 Editing: Cynthia Rockwell 'Monica Garcia Layout: Azar Soheil Jokilehto Organization and coordination: Giorgio Torraca Daniela Ferragni Jef Malliet © ICCROM 1985 Via di San Michele 13 00153 Rome RM, Italy Printed in Italy Sintesi Informazione S.r.l. CONTENTS page Introduction CROSSLEY David W. The conservation of monuments connected with the iron and steel industry in the Sheffield region. 1 PETRIE Angus J. The No.1 Smithery, Chatham Dockyard, 1805-1984 : 'Let your eye be your guide and your money the last thing you part with'. 15 BJORKENSTAM Nils The Swedish iron industry and its industrial heritage. 37 MAGNUSSON Gert The medieval blast furnace at Lapphyttan. 51 NISSER Marie Documentation and preservation of Swedish historic ironworks. 67 HAMON Francoise Les monuments historiques et la politique de protection des anciennes forges. 89 BELHOSTE Jean Francois L'inventaire des forges francaises et ses applications. 95 LECHERBONNIER Yannick Les forges de Basse Normandie : Conservation et reutilisation. A propos de deux exemples. 111 RIGNAULT Bernard Forges et hauts fourneaux en Bourgogne du Nord : un patrimoine au service de l'identite regionale. 123 LAMY Yvon Approche ethnologique et technologique d'un site siderurgique : La forge de Savignac-Ledrier (Dordogne). 149 BALL Norman R. A Canadian perspective on archives and industrial archaeology. 169 DE VRIES Dirk J. Iron making in the Netherlands. 177 iii page FERRAGNI Daniela, MALLIET Jef, TORRACA Giorgio The blast furnaces of Capalbio and Canino in the Italian Maremma. -

ITP Steel: Recycling and Reuse of Basic Oxygen Furnace (BOF)

STEELSTEEL Project Fact Sheet RECYCLING AND REUSE OF BASIC OXYGEN FURNACE (BOF)/BASIC OXYGEN PROCESS (BOP) STEELMAKING SLAGS BENEFITS NEW TECHNOLOGIES AND METHODOLOGIES MAY ALLOW VALUE- • Iron recovered from BOF slag saves 10 ADDED UTILIZATION OF STEELMAKING SLAG THUS REDUCING WASTE million British thermal units (Btu) per AND USE OF LANDFILLS, AND SAVING ENERGY ton of new steel The U.S. steel industry generates about 30 million tons of by-products each • Recovery contributes to higher percent- year, including six million tons of BOF/BOP slag. The recycling of blast age of iron units being converted to steel furnace (BF) slag has made significant progress in past years with much of • Use of slag component for AMD the material being utilized as construction aggregate and in cementitious applications. However, the recycling of BOF/BOP slag still faces many neutralization applications in abandoned technical, economical, and environmental challenges. Previous efforts have coal mines focused on in-plant recycling of the by-products, achieving limited success. • Minimize the potential of alkalinity run- As a result, large amounts of by-products of various qualities have been off at mill sites stockpiles at steel mills or disposed into landfills. Michigan Technological University (MTU) is developing an integrated system of technologies to recover the iron value from BOF steelmaking slag and to divert the residual non-iron bearing fraction into a feedstock for the manufac- ture of acid mine drainage (AMD) neutralizing agent. In this project, technolo- gies are being developed to separate iron from the BOF slag and prepare those iron units for furnace charge. -

From Bloomery Furnace to Blast Furnace Archeometallurgical Analysis of Medieval Iron Objects from Sigtuna and Lapphyttan, Sverige

EXAMENSARBETE INOM TEKNIK, GRUNDNIVÅ, 15 HP STOCKHOLM, SVERIGE 2019 From Bloomery Furnace to Blast Furnace Archeometallurgical Analysis of Medieval Iron Objects From Sigtuna and Lapphyttan, Sverige ANDREAS HELÉN ANDREAS PETTERSSON KTH SKOLAN FÖR INDUSTRIELL TEKNIK OCH MANAGEMENT Abstract During the Early Middle Ages, the iron production in Sweden depended on the bloomery furnace, which up to that point was well established as the only way to produce iron. Around the Late Middle Ages, the blast furnace was introduced in Sweden. This made it possible to melt the iron, allowing it to obtain a higher carbon composition and thereby form new iron-carbon phases. This study examines the microstructure and hardness of several tools and objects originating from archaeological excavations of Medieval Sigtuna and Lapphyttan. The aim is to examine the differences in quality and material properties of iron produced by respectively blast furnaces and bloomery furnaces. Both methods required post-processing of the produced iron, i.e. decarburization for blast furnaces and carburization for bloomeries. These processes were also studied, to better understand why and how the material properties and qualities of the items may differ. The results show that some of the studied items must have been produced from blast furnace iron, due to their material composition and structure. These items showed overall better material quality and contained less slag. This was concluded because of the increased carbon concentration that allowed harder and more durable structures such as pearlite to form. The study also involved an investigation of medieval scissors, also known as shears, made from carburized bloomery furnace iron.