Crop Profile for Small Grains in North Carolina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanitation in Grain Storage and in Mills

Sanitation in grain storage and in mills Bhadriraju Subramanyam, PhD Professor Department of Grain Science and Industry Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 66506, USA Tel: 785-532-4092 Fax: 785-532-7010 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.ksre.ksu.edu/grsc_subi IAOM 4th Annual SE Asia District Conference October 8-10, 2013 Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam Pests associated with feed facilities Invertebrate pests: Filth flies Cockroaches Mites Stored-product insects Vertebrate pests: Birds Rats and mice (rodents) Unsanitary conditions in mills Birds Product damage and loss Contamination of food or damage to food • Cleaning costs • Food destruction • Risk of prosecution • Loss of sales Safety hazard Slippery when wet… Sanitation • Grain stored in bins/silos (whole grains) –Removal of dockage/spillage • Processed material in the feed mill/warehouse –GMPs Sanitation of grain • In grain sanitation refers to removal of broken kernel, grain dust, weed seeds, etc • Sources – Grain damage due to harvesting machinery – Manual vs hand threshing – Multiple handling (corn more susceptible to breakage) • Grain handling produces 0.11-0.55% dust by wt • Corn lot subjected to 2.5, 5, and 15 transfers had 0.9, 4, and 9% breakage, respectively – Corn breakage susceptibility inversely related to moisture – Penalties at time of sale – Internal insects produce broken kernels and/or grain dust Dockage in grain • Corn with 2-3% dockage had 50% of it accumulated in the spout line area • Some accumulate below false floors of steel bins • High moisture area • Insects and molds proliferate in this area Insects in grain residues at elevators (Arthur et al. -

Spoilage and Heating of Stored Agricultural Products

Spoilage and heating of stored agricultural products Prevention, detection, and control 1 Publication 1823E 1989 Spoilage and heating of stored agricultural products Prevention, detection, and control J.T. Millls Research Station, Winnipeg, Man. Research Branch Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada 2 ©Minister of Supply and Services Although the information contained Canada 1989 in this manual has been carefully researched, neither the author nor Available in Canada through Agriculture Canada can accept responsibility for any problems Authorized Bookstore Agents and that may arise as a result of its other bookstores application. Specific mention of a product type, brand name, or or by mail from company does not constitute endorsement by the Government of Canadian Government Publishing Canada or by Agriculture Canada. Centre Supply and Services Canada Recommendations for pesticide use Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 in this publication are intended as guidelines only. Any application of Price subject to change without a pesticide must be in accordance notice with directions printed on the product label of that pesticide as prescribed Cat. No. A53-1823/1988E ISBN 0 under the Pest Control Products Act. 660-13043-2 Always read the label. A pesticide should also be recommended by Staff editor provincial authorities. Because Sheilah V. Balchin recommendations for use may vary from province to province, your provincial agricultural representative should be consulted for specific advice. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Mills, J.T. (John T.) Spoilage and heating of stored agricultural products: prevention, detection and control (Publication: 1823E) Includes index. Bibliography: p. 1. Farm produce -Storage - Diseases and injuries. I. Title. II. Series: Publication (Canada. -

Grain Grading Primer

f •4 A H GRAIN GRADING PRIMER AGRICULTURE HANDBOOK NO. 59 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE THE Grain Grading Primer is designed for grain farmers and country grain dealers who are inter- ested in handling grain on a grade and quality basis and for marketing students. It is not designed for grain inspectors, for they must necessarily use a more precise and detailed grain-grading technique than that described herein. A number of farm practices that lower the quality and grade of grain are briefly discussed in this publi- cation. Methods and apparatus useful in measuring the value of grain are described and information on how to inspect and grade grain is given. This revision of the Primer covers changes in the rye grades that became effective Jiily 1, 1951. The new Malting grades for Hannchen and Hanna barley are included in appendix I, and a new section on grading procedures for each grain has been added as appendix IL The Handbook of Official (xrain Standards of the United States, for sale by the Superintendent of Doc- uments, U. S. Government Printing Office, Wash- ington 25, D. C, at 25 cents a copy, and other reference material listed on pages 59 and 60 of this Primer will provide useful supplementary reading. This manual is a slight revision of Miscellaneous Publication 325. V^ashington, D. C. Issued July 1953 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. — Price 20 cents GRAIN GRADING PRIMER By Willis B. Combs, senior marketing specialist, Extension Service, and Fred G. -

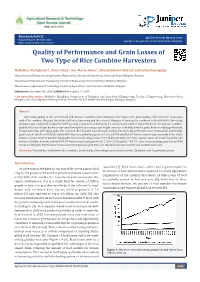

Quality of Performance and Grain Losses of Two Type of Rice Combine Harvesters

Research Article Agri Res & Tech: Open Access J Volume 19 Issue 2 - December 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Modather Mairghany DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.19.556085 Quality of Performance and Grain Losses of Two Type of Rice Combine Harvesters Modather Mairghany1*, Azmi Yahya1, Nor Maria Adam2, Ahmad Suhaizi Mat Su3 and Suha Elsoragaby1 1Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia 3Department of Agricultural Technology, Faculty of Agriculture, University Putra Malaysia, Malaysia Submission: December 03, 2018, Published: December 17, 2018 *Corresponding author: Modather Mairghany, Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University Putra Malaysia, (18-18) A Skyvillas Serdang Perdana Street No SP 3/5 43300 Seri Kembangan Selangor, Malaysia. Abstract Harvesting quality of the conventional and mid-size combines was evaluated on the basis of the grain quality collected in the clean grain Qualitytank of theof threshed combine, mass the grainhas been loss expressed in the field through after harvesting the percentage and the and extent weight of contentdamages of of a runninghealthy (whole)the combines grain, onbroken the field or damaged plot. Harvesting kernels, foreignoperation materials, was conducted and empty on farmers’grain. The field collected lots with thresh a total grains area from of 30.104 the mid-combine ha for conventional harvester combine showed and 0.49% 16.95 more ha for mean the wholemid-size and combine. healthy grain content (96.47 vs 87.32%) and 69.63% lesser mean broken grain (0.72 vs 2.37%) and 89.96% lesser mean foreign materials in the outlet mixture of grain (2.18 vs 4.05%) and 46.23% lesser mean empty grain of rice (0.63 vs 6.28%). -

Chapter 9. Arthropods of Cereal Crops in Canadian Grasslands

217 Chapter 9 Arthropods of Cereal Crops in Canadian Grasslands John Gavloski Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives, Crops Knowledge Centre, 65 3rd Ave. NE, Carman, Manitoba, Canada R0G 0J0 Scott Meers Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development, 301 Horticultural Station Road East, S.S. #4, Brooks, Alberta, Canada T1R 1E6 Abstract. Cereal crops are a major aspect of the Canadian prairie landscape. This chapter focuses on insects of small grain cereals (wheat, oats, barley, and rye), but not on larger grains such as corn, which are less abundant on the Canadian prairies. Settlement of the Canadian prairies resulted in the replacement of vast amounts of native prairie plants with cereal crops. Many native insects adapted and flourished in this new habitat. Many alien insect species have also been accidentally introduced and are now pests of cereal crops. Other insects have been purposely introduced to regulate the populations of insect pests of cereal crops. Insect species are presented in feeding guilds in this chapter. Insects within a feeding guild feed on the same or a similar resource and may at times compete for this resource. Changes in cropping practices and varieties can also have an impact on the insect communities on cereal crops. Such interactions will also be described. Résumé. Les cultures de céréales occupent une place très importante dans le paysage des prairies canadiennes. Le présent chapitre porte principalement sur les insectes qui s’attaquent aux petites céréales (blé, avoine, orge et seigle), et non sur ceux qui se nourrissent de céréales à graines plus grosses — par exemple, le maïs — moins abondantes dans les prairies canadiennes. -

Mycotoxin Reduction in Grain Chains

Mycotoxin Reduction in Grain Chains John F. Leslie & Antonio F. Logrieco Mycotoxin Reduction in Grain Chains Mycotoxin Reduction in Grain Chains Edited by JOHN F. LESLIE Department of Plant Pathology Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas, USA ANTONIO F. LOGRIECO Institute of Sciences of Food Production (ISPA) National Research Council (CNR) Bari, Italy This edition first published 2014 © 2014 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Editorial offices: 1606 Golden Aspen Drive, Suites 103 and 104, Ames, Iowa 50010, USA The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyrighted material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by Blackwell Publishing, provided that the base fee is paid directly to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923. For those organizations that have been granted a photocopy license by CCC, a separate system of payments has been arranged. The fee codes for users of the Transactional Reporting Service are ISBN-13: 978-0-8138-2083-5/2014. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Distribution of Damage in Maize Combine Cylinder and Relationship Between Physico-Rheological Properties of Shelled Grain and Da

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1972 Distribution of damage in maize combine cylinder and relationship between physico-rheological properties of shelled grain and damage Ali Ramadan Mahmoud Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Mahmoud, Ali Ramadan, "Distribution of damage in maize combine cylinder and relationship between physico-rheological properties of shelled grain and damage " (1972). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5935. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5935 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iNFORMATIOlM TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. -

Current Maize Production, Postharvest Losses and the Risk of Mycotoxins Contamination in Tanzania Rashid A

Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Conference Proceedings and Presentations 7-2015 Current Maize Production, Postharvest Losses and the Risk of Mycotoxins Contamination in Tanzania Rashid A. Suleiman Iowa State University, [email protected] Kurt A. Rosentrater Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/abe_eng_conf Part of the Agriculture Commons, Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons, and the Food Security Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ abe_eng_conf/442. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Conference Proceedings and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Current Maize Production, Postharvest Losses and the Risk of Mycotoxins Contamination in Tanzania Abstract Agriculture is the backbone of Tanzanian economy. It accounts for about one-third of the gross domestic product (GDP), provides 85 percent of all exports and saves as a livelihood to over 80 percent of the total population. Maize is the primary staple crop; it’s grown in nearly all agro-ecological zones in the country. Tanzania is a major maize producer in Sub-Saharan Africa. In the last four decades, Tanzania has ranked among the top 25 maize producing countries in the world. -

Characterising Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats in Producing Naked Oat As a Novel Crop for Northern Growing Conditions

AGRICULTURAL AND FOOD SCIENCE Vol. 13 (2004): 212–228. Review article Characterising strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in producing naked oat as a novel crop for northern growing conditions Pirjo Peltonen-Sainio MTT Agrifood Research Finland, Plant Production Research, FIN-31600 Jokioinen, Finland, e-mail: [email protected] Anna-Maija Kirkkari Work Efficiency Institute, PO Box 13, FIN-05201 Rajamäki, Finland Lauri Jauhiainen MTT Agrifood Research Finland, Data and Information Services, FIN-31600 Jokioinen, Finland Naked oat (Avena sativa ssp. nuda L.) is the highest quality small-grain cereal that can be grown at the northernmost margin of cereal production. It remains an under-utilised crop and it contributes less than 0.1% to the total oat area in Finland. In general, limited interest in growing naked oat more extensively is attributed to its weaknesses, which ironically result from nakedness that improves the quality of the crop. This paper reviews the available literature and assesses the balance of the argu- ments for and against naked oats. Results from the study were transformed into quantitative variables and analysed for strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) using an analytical hierar- chical process. As the importance of different SWOT-factors depends largely on targeted end-use of yield, separate analyses were done for use of naked oats as on-farm feed and as an input for the feed and food industry. If we aim at increasing area under naked oat in Finland, the most feasible starting point would be on-farm feed. In this case, strengths (high nutritional quality and energy content) out- weighed weaknesses (sensitivity to grain damage) and threats (problems in germination). -

Investigation of Methods for Real Time Determination of Grain Damage

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2002 Investigation of methods for real time determination of grain damage Michael A. Brand Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Brand, Michael A., "Investigation of methods for real time determination of grain damage" (2002). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 19799. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/19799 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Investigation of methods for real time determination of grain damage by Michael A. Brand A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Agricultural Engineering (Agricultural Power and Machinery) Program of Study Committee: Graeme Quick, Co-major Professor Carl Bern, Co-major Professor Stuart Birrell Dan Nettleton Brian Steward Bruce Warman Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2002 Copyright ©Michael A. Brand, 2002. All rights reserved. 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Michael A. Brand has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGI:TRES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1X CHAPTER ONE. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 1 Thesis Organization 4 Literature Review 4 References 27 CHAPTER TWO. -

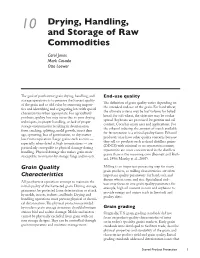

10 Drying, Handling, and Storage of Raw Commodities

10 Drying, Handling, and Storage of Raw Commodities Carol Jones Mark Casada Otto Loewer The goal of postharvest grain drying, handling, and End-use quality storage operations is to preserve the harvest quality The definition of grain quality varies depending on of the grain and to add value by removing impuri- the intended end-use of the grain. For hard wheat, ties and identifying and segregating lots with special the ultimate criteria may be loaf volume for baked characteristics when appropriate. For agricultural bread; for soft wheat, the objective may be cookie products, quality loss may occur due to poor drying spread. Soybeans are processed for protein and oil techniques, improper handling, or lack of proper content. Corn has many uses and applications. For storage environments resulting in deterioration the ethanol industry, the amount of starch available from cracking, splitting, mold growth, insect dam- for fermentation is a critical quality factor. Ethanol age, sprouting, loss of germination, or dry matter producers may have other quality concerns because loss from respiration. Large grains such as corn — they sell co-products such as dried distillers grains especially when dried at high temperatures — are (DDGS) with minimal or no mycotoxin content; particularly susceptible to physical damage during mycotoxins are more concentrated in the distillers handling. Physical damage also makes grain more grains than in the incoming corn (Bennett and Rich- susceptible to invasion by storage fungi and insects. ard, 1996; Murthy et al., 2005). Grain Quality Milling is an important processing step for many grain products, so milling characteristics are often Characteristics important quality parameters for hard, soft, and durum wheat; corn; and rice. -

Effects of Grain Moisture, Drying Methods, and Variety on Breakage

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1986 Effects of grain moisture, drying methods, and variety on breakage susceptibility of shelled corn as measured by the Wisconsin Breakage Tester Pradip Kumar Dutta Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Dutta, Pradip Kumar, "Effects of grain moisture, drying methods, and variety on breakage susceptibility of shelled corn as measured by the Wisconsin Breakage Tester " (1986). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 8242. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/8242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.