Dispute Between Danzig and Stephen Bathory on the Character of Power in the 16Th‑Century Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15Th-17Th Century) Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary (15Th-17Th Century) Edited by Giovanna Siedina

45 BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Giovanna Siedina Giovanna Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) Civilization in the Slavic World of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Essays on the Spread (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FUP FIRENZE PRESUNIVERSITYS BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI ISSN 2612-7687 (PRINT) - ISSN 2612-7679 (ONLINE) – 45 – BIBLIOTECA DI STUDI SLAVISTICI Editor-in-Chief Laura Salmon, University of Genoa, Italy Associate editor Maria Bidovec, University of Naples L’Orientale, Italy Scientific Board Rosanna Benacchio, University of Padua, Italy Maria Cristina Bragone, University of Pavia, Italy Claudia Olivieri, University of Catania, Italy Francesca Romoli, University of Pisa, Italy Laura Rossi, University of Milan, Italy Marco Sabbatini, University of Pisa, Italy International Scientific Board Giovanna Brogi Bercoff, University of Milan, Italy Maria Giovanna Di Salvo, University of Milan, Italy Alexander Etkind, European University Institute, Italy Lazar Fleishman, Stanford University, United States Marcello Garzaniti, University of Florence, Italy Harvey Goldblatt, Yale University, United States Mark Lipoveckij, University of Colorado-Boulder , United States Jordan Ljuckanov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Bulgaria Roland Marti, Saarland University, Germany Michael Moser, University of Vienna, Austria Ivo Pospíšil, Masaryk University, Czech Republic Editorial Board Giuseppe Dell’Agata, University of Pisa, Italy Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th-17th Century) edited by Giovanna Siedina FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRESS 2020 Essays on the Spread of Humanistic and Renaissance Literary Civilization in the Slavic World (15th- 17th Century) / edited by Giovanna Siedina. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2020. -

Poles Under German Occupation the Situation and Attitudes of Poles During the German Occupation

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/poles-under-german-occu/15596,Poles-under-German-Occupation.html 2021-09-25, 22:48 Poles under German Occupation The Situation and Attitudes of Poles during the German Occupation The Polish population found itself in a very difficult situation during the very first days of the war, both in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in The General Government. The policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Executions, resettlements, arrests, deportations to camps, and street round-ups were a constant element of the everyday life of Poles during the war. Initially the policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Food rationing was imposed in cities and towns, with food coupons covering about one-third of a person’s daily needs. Levies — obligatory, regular deliveries of selected produce — were introduced in the countryside. Farmers who failed to deliver their levy were subject to severe repressions, including the death penalty. Devaluation and difficulty with finding employment were the reason for most Poles’ poverty and for the everyday problems in obtaining basic products. The occupier also limited access to healthcare. The birthrate fell dramatically while the incidence of infectious diseases increased significantly. -

I. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE the Manuscript of Jan Strzembosz and His Book Collection Have Not Been Deprived of the Attention of Polish Scholaraship

ORGANON 26-27:1997-1998 AUTEURS ET PROBLEMES Tomasz Strzembosz (Poland) JAN STRZEMBOSZ (1545-1606) HIS MANUSCRIPT AND COLLECTION OF BOOKS I. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE The manuscript of Jan Strzembosz and his book collection have not been deprived of the attention of Polish scholaraship. The manuscript has been studied by Witold Rubczynski (1922), who, as Aleksander Birken- majer observed, "knew very little about its author". In fact his knowledge was "less than very little". The book collection has received the scholarly regard of many others, writing at diverse times. But none of it has amounted to more than just brief notes, not providing much information about the library collection and its history, and next to none about its original owner. Today, in an age marked by a heightened interest in the Renaissance, Strzem bosz’ valuable bibliophile bequest is a worthy subject for academic attention, while the life and achievements of the enlightened and public-spirited col lector who endowed us with it merit a few moments of notice. A compilation of the facts published earlier and more recently with the material preserved in the archives and collected still before the Second World War, which has fortunately managed to survive that War, will help to give us a fuller picture of the figure of Jan Strzembosz. In 1538 at Opoczno (now Central Poland), on a date recorded as "f. 5 post Conductum Paschae" the Strzembosz brothers, Mikołaj, the Reverend Andrzej, Derstaw, and Ambroży, sons of Jan Strzembosz of Jablonica and Wieniawa, and later of Dunajewice and Skrzyńsko, Justice of the Borough of Radom1, and Owka (Eufemia), daughter of Dersław Dunin of Smogorze- wo, Lord Crown Treasurer, and Małgorzata of Przysucha, concluded an act for the distribution of the patrimonial and maternal property left to them. -

Short History of Kashubes in the United States

A short history of Kashubs in the United States Kashubs are a Western Slavic nation, who inhabited the coastline of the Baltic Sea between the Oder and Vistula rivers.Germanization or Polonization were heavy through the 20th century, depending on whether the Kingdom of Prussia or the Republic of Poland governed the specific territory. In 1919, the Kashubian-populated German province of West Prussia passed to Polish control and became the Polish Corridor. The bulk of Kashubian immigrants arrived in the United States between 1840 and 1900, the first wave from the highlands around Konitz/Chojnice, then the Baltic coastline west of Danzig/Gdansk, and finally the forest/agricultural lands around and south of Neustadt/Wejherowo. Early Kashubs settled on the American frontier in Michigan (Parisville and Posen), Wisconsin (Portage and Trempealeau counties), and Minnesota (Winona). Fishermen settled on Jones Island along Lake Michigan in Milwaukee after the U.S. Civil War. Until the end of the 19th century, various railroad companies recruited newcomers to buy cheap farmland or populate towns in the West. This resulted in settlements in western Minnesota, South Dakota, Missouri, and central Nebraska. With the rise of industrialization in the Midwest, Kashubs and natives of Posen/Poznan took the hot and heavy foundry, factory, and steel mill jobs in cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh. In 1900, the number of Kashubs in the United States was estimated at around 100,000. The Kashubs did not establish a permanent immigrant identitybecause larger communities of Germans and Poles outnumbered them. Many early parishes had Kashubian priests and parishioners, but by 1900, their members were predominantly Polish. -

Pobierz Plik Metryka Nacji Polskiej W Padwie 1592–1745

ALBUM POLONICUM Metryka nacji polskiej w Padwie: 1592–1745. Edycja fototypiczna. Tom I, część I Registri di immatricolazione della nazione polacca a Padova: 1592–1745. Edizione fototipica. Vol. I, parte I Metrica of the Polish Nation in Padua: 1592–1745. The phototypic edition. Vol. I, part I Natio Polona. Fontes et Studia I Redakcja naukowa serii: / Collana a cura di: / Scientific editor of the series: Mirosław Lenart Wydawca: / Editore: / Publishing: Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kulturowego za Granicą POLONIKA ul. Madalińskiego 101, 02-549 Warszawa www.polonika.pl Współpraca redakcyjna: / Cooperazione editoriale: / Editorial cooperation: Magdalena Gutowska, Piotr Jamski Redakcja: / Redazione: / Editorial: Renata Gajowiak, Małgorzata Iżykowska Tłumaczenia: / Traduzione: / Translations: Zbigniew Pyż (English), Serafina Santoliquido (Italiano) Dokumentacja fotograficzna: / Documentazione fotografica: / Photographic documentation: Piotr Jamski lb Projekt graficzny / Grafica: / Graphic design: Katarzyna Brzostowska u Druk: / Stampa: / Printing: A m Metryka nacji polskiej w Padwie Drukarnia EDIT í ul. Dworkowa 2 Registri di immatricolazione della nazione polacca a Padova 05-462 Wiązowna Metrica of the Polish Nation in Padua © Copyright: Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kulturowego za Granicą POLONIKA, 2018 m Eliminare L'Nazionale per il Patrimonio Culturale Polacco all'Estero POLONIKA, 2018 The POLONIKA National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage Abroad, 2018 Po nicu ISBN 978-83-66172-06-7 Wydanie 1, Warszawa 2018 / I -

German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Paper HEC No. 2004/1 The Expulsion of the ‘German’ Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War Edited by STEFFEN PRAUSER and ARFON REES BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) All rights reserved. No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form without permission of the author(s). © 2004 Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees and individual authors Published in Italy December 2004 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50016 San Domenico (FI) Italy www.iue.it Contents Introduction: Steffen Prauser and Arfon Rees 1 Chapter 1: Piotr Pykel: The Expulsion of the Germans from Czechoslovakia 11 Chapter 2: Tomasz Kamusella: The Expulsion of the Population Categorized as ‘Germans' from the Post-1945 Poland 21 Chapter 3: Balázs Apor: The Expulsion of the German Speaking Population from Hungary 33 Chapter 4: Stanislav Sretenovic and Steffen Prauser: The “Expulsion” of the German Speaking Minority from Yugoslavia 47 Chapter 5: Markus Wien: The Germans in Romania – the Ambiguous Fate of a Minority 59 Chapter 6: Tillmann Tegeler: The Expulsion of the German Speakers from the Baltic Countries 71 Chapter 7: Luigi Cajani: School History Textbooks and Forced Population Displacements in Europe after the Second World War 81 Bibliography 91 EUI WP HEC 2004/1 Notes on the Contributors BALÁZS APOR, STEFFEN PRAUSER, PIOTR PYKEL, STANISLAV SRETENOVIC and MARKUS WIEN are researchers in the Department of History and Civilization, European University Institute, Florence. TILLMANN TEGELER is a postgraduate at Osteuropa-Institut Munich, Germany. Dr TOMASZ KAMUSELLA, is a lecturer in modern European history at Opole University, Opole, Poland. -

Ann-Kathrin Deininger and Jasmin Leuchtenberg

STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS WOMEN AND THE GENDER OF SOVEREIGNTY IN EUROPEAN CULTURE EDITED BY ANKE GILLEIR AND AUDE DEFURNE Leuven University Press This book was published with the support of KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). Selection and editorial matter © Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne, 2020 Individual chapters © The respective authors, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. Attribution should include the following information: Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne (eds.), Strategic Imaginations: Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ISBN 978 94 6270 247 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 350 4 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 351 1 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663504 D/2020/1869/55 NUR: 694 Layout: Coco Bookmedia, Amersfoort Cover design: Daniel Benneworth-Gray Cover illustration: Marcel Dzama The queen [La reina], 2011 Polyester resin, fiberglass, plaster, steel, and motor 104 1/2 x 38 inches 265.4 x 96.5 cm © Marcel Dzama. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner TABLE OF CONTENTS ON GENDER, SOVEREIGNTY AND IMAGINATION 7 An Introduction Anke Gilleir PART 1: REPRESENTATIONS OF FEMALE SOVEREIGNTY 27 CAMILLA AND CANDACIS 29 Literary Imaginations of Female Sovereignty in German Romances -

Public Buildings and Urban Planning in Gdańsk/Danzig from 1933–1945

kunsttexte.de/ostblick 3/2019 - 1 Ja!oda ?a5@ska-Kaczko &ublic .uildin!s and Brban &lannin! in "da#sk/$anzi! fro% 193321913 Few studies have discussed the Nazi influence on ar- formation of a Nazi-do%inated Denate that carried chitecture and urban lanning in "dańsk/Danzig.1 Nu- out orders fro% .erlin. /he Free Cit' of $anzi! was %erous &olish and "erman ublications on the city’s formall' under the 7ea!ue of Nations and unable to history, %onu%ent reservation, or *oint ublications run an inde endent forei!n olic') which was on architecture under Nazi rule offer only !eneral re- entrusted to the Fe ublic of &oland. However) its %arks on local architects and invest%ents carried out newl' elected !overn%ent had revisionist tendencies after 1933. +ajor contributions on the to ic include, a and i% le%ented a Jback ho%e to the FeichK %ono!ra h b' Katja .ernhardt on architects fro% the a!enda <0ei% ins Feich=. 4ith utter disre!ard for the /echnische 0ochschule $anzig fro% 1904–1945,2 rule of law) the new authorities banned o osition .irte &usback’s account of the restoration of historic and free ress) sought to alter the constitution) houses in the cit' fro% 1933–1939,3 a reliminary %ar!inalized the Volksta!) and curtailed the liberties stud' b' 4iesław "ruszkowski on unrealized urban of &olish and 8ewish citizens) the ulti%ate !oal bein! lanning rojects fro% the time of 4orld 4ar 66)1 their social and econo%ic exclusion. 6n so doin!) the which was later develo ed b' &iotr Lorens,3 an ex- Free Cit' of $anzi! sou!ht to beco%e one with the tensive reliminary stud' and %ono!ra h b' 8an Feich. -

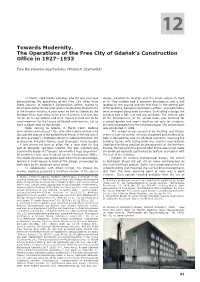

Towards Modernity. the Operations of the Free City of Gdańsk's

12 Towards Modernity. The Operations of the Free City of Gdańsk’s Construction Office in 1927–1933 Ewa Barylewska-Szymańska, Wojciech Szymański In March 1928 Martin Kießling, who for one year was design, keeping its location and the small square in front administering the operations of the Free City (then Freie of it.3 Two schools had a common gymnasium and a hall Stadt Danzig) of Gdańsk’s Construction Office, moved to located on the ground and the first floor in the central part Berlin to become the Director of the Construction Department of the building. Spacious classrooms, offices, and workrooms in the Finance Ministry. A year spent by him in Gdańsk by the were arranged along wide corridors. In Kießling’s design the Motława River may seem to be a short period; however, the building had a flat roof and big windows. The interior part effects of his operations and their impact turned out to be of the development, at the school back, was destined for very important for the history of Gdańsk architecture1. Let us a school garden and sports facilities not only for students, have a closer look at this period. but also for people from the neighbourhood. The construction Upon coming to Gdańsk in March 1927, Kießling was completed in 1929. immediately started to act.2 One of the first tasks undertaken by The school design prepared by Kießling and Krüger him was the change of the architectural design of the folk school refers to historic motifs, strongly simplified and modernized, for girls and boys in Pestalozzi Street in Gdańsk-Wrzeszcz. -

Themis Clothed in Ermine. Some Remarks on the Jurisdiction Excercised by the Rector of Krakow Academy*

Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 2014; 7 (1), s. 147–157 doi: 10.4467/20844131KS.14.011.2252 www.ejournals.eu/Krakowskie-Studia-z-Historii-Panstwa-i-Prawa DOROTA MALEC Jagiellonian University in Kraków Themis Clothed in Ermine. Some Remarks on the Jurisdiction Excercised by the Rector of Krakow Academy* Abstract The scope of the jurisdiction of the Rector of the Krakow Academy was determined by the foundation privileges of Kazimierz Wielki and Władysław Jagiełło; the latter had subsequently been extended by the university statutes as well as by the royal and urban documents. The judicial competence of the Rector, named in legal documents as the “highest judge”, referred above all to members of the univer- sity corporation, but also to people remaining outside this structure (e.g. in some cases to the Krakow townsmen). The Rector assumed the jurisdiction the moment he had taken an oath. The students and professors of the Krakow Academy were also subject to the Rector’s judicial authority, the moment they had taken an oath. The subject range of the Rector’s jurisdiction comprised penal cases, including those relating to disciplinary issues. The jurisdiction also extended to civil law: confi rmation of documents, certain institutions of inheritance law and even civil contentions relating to copyright law. The Rector adjudicated on the basis of canon law, Roman law and customary law as well as on the basis of the uni- versity statutes. The procedure was based on a shortened and simplifi ed mode derived from canon law. The trial was of an adversarial nature and consequently, the penal and civil proceedings did not differ much one from another. -

Vergangenheitsbewältigung and the Danzig Trilogy

vergangenheitsbewältigung and the danzig trilogy Joseph Schaeffer With the end of the Second World War in 1945, Germany was forced to examine and come to terms with its National Socialist era. It was a particularly difficult task. Many Germans, even those who had suspected the National Socialist crimes, were shocked by the true barbarity of the Nazi regime. Günter Grass, who spent 1945 in an American POW camp listening to the Nurem- berg Trials, was one of those Germans. How could the Holocaust have arisen from the land of poets and philosophers? German authors began to seek the answer to this question immediately following the end of WWII, and this pursuit naturally led to several different genres of German post-war literature. Some authors adopted the style of Kahlschlag (clear cutting), in which precise use of language would free German from the propaganda-laden connotations of Goebbel’s National Socialist Germany. Others spoke of a Stunde Null (Zero Hour), a new beginning without reflec- tion upon the past. These styles are easily recognizable in the works of early post-war authors like Alfred Andersch, Günter Eich, and Wolfgang Borchert. However, it would take ten years before German authors adopted the style of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, an analysis and overcom- ing of Germany’s past.1 In 1961 Walter Jens wrote that only works written after 1952 should be considered part of the genre of German post-war literature (cited in Cunliffe 3). Without a distanced analysis of the Second World War an author would be unable to produce a true work of art. -

Miriam Weiner Archival Collection Fordon, Poland

MIRIAM WEINER ARCHIVAL COLLECTION FORDON, POLAND – Collection Description According to Wikipedia: "At some point Fordon was located in the Grand Duchy of Posen and later under direct Prussian control. It was returned to Poland at the end of the First World War. In 1939 it was incorporated by the Third Reich. It is estimated that during World War II German soldiers killed from 1200 to 3000 people, mainly Poles and Jews, in the Death Valley of Fordon (Valley of Death (Bydgoszcz)). The exact number stays unknown as historians have not found appropriate documents that would state the final number of deaths. Finally, in 1945 Fordon was liberated from Nazi occupation. In 1950 Fordon was still a separate town from Bydgoszcz. At that time it was described as "seven miles east" of the latter city. It had a population of 3,514 people and manufactured such things as cement and paper.[1] In 1973 Fordon became a part of the city of Bydgoszcz." Valley of Death (Polish: Dolina Zmierci) in Fordon, Bydgoszcz, northern Poland, is a site of Nazi German mass murder committed at the beginning of World War II and a mass grave of 1,200 – 1,400 Poles and Jews murdered in October and November 1939 by the local German Selbstschutz and the Gestapo.[1][2] The murders were a part of Intelligenzaktion in Pomerania, a Nazi action aimed at the elimination of the Polish intelligentsia in Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia, which included the former Pomeranian Voivodeship ("Polish Corridor"). It was part of a larger genocidal action that took place in all German occupied Poland, code-named Operation Tannenberg.[3] Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valley_of_Death_(Bydgoszcz) Fordon, Poland - Page 2 Included in the Surname Database are the following documents for this town: Birth records 1823 / 1866 Marriage records 1824 / 1860 Death records 1842 / 1859 The foregoing documents trace the Rosenbaum family (and related families including Barnass and Oser) through one family member who came to the U.S.