Whakatakapokai Social Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMPASS Research Centre Barry Milne and Nichola Shackleton

New New Zealand Data Quality of the 2018 New Zealand Census Barry Milne COMPASS Seminar Tuesday, 3 March 2020 The University of Auckland The University of Outline Background to the Census What happened with Census 2018? Why did it happen? What fixes were undertaken? What are the data quality implications? New New Zealand 1. Population counts 2. Electoral implications 3. Use of alternative data sources 4. Poor/very poor quality variables Guidelines for users of the Census The University of Auckland The University of Some recommendations that (I think) should be taken on board 2 Background New Zealand Census of Population and Dwellings Official count of how many people and dwellings there are in the country at a set point in time (by age, sex, ethnicity, region, community) Detailed social, cultural and socio-economic information about the total New Zealand population and key groups in the population Undertaken since 1851, and every five years since 1881, with exceptions New New Zealand • No census during the Great Depression (1931) • No census during the Second World War (1941) • The 1946 Census was brought forward to September 1945 • The Christchurch earthquakes caused the 2011 Census to be re-run in 2013 Since 1966, held on first Tuesday in March of Census year The most recent census was undertaken on March 6, 2018 The University of Auckland The University of http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/info-about-the-census/intro-to-nz-census/history/history-summary.aspx 3 Background Census is important for Electorates and electoral boundaries Central and local government policy making and monitoring Allocating resources from central government to local areas Academic and market research Statistical benchmarks New New Zealand A data frame to select samples for social surveys Many other things beside… “every dollar invested in the census generates a net benefit of five dollars in the economy” (Bakker, 2014, Valuing the census, p. -

Benchmark Survey of the New Zealand Public's Knowledge And

Benchmark survey of the New Zealand public’s knowledge and understanding of the First World War and its attitudes to centenary commemorations Report prepared for: First World War Centenary Programme Office Contact person: Colmar Brunton Date: 4 March 2013 Table of Contents Executive summary..........................................................................................................................................3 Conclusions......................................................................................................................................................6 Background and objectives..............................................................................................................................8 Research methodology ....................................................................................................................................9 Survey results ................................................................................................................................................11 Interest in history and engagement in learning about history.........................................................................11 History ..........................................................................................................................................................11 Local community history ..............................................................................................................................13 Genealogy.....................................................................................................................................................15 -

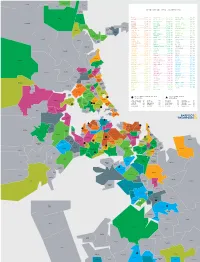

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

South & East Auckland

G A p R D D Paremoremo O N R Sunnynook Course EM Y P R 18 U ParemoremoA O H N R D E M Schnapper Rock W S Y W R D O L R SUNSET RD E R L ABERDEEN T I A Castor Bay H H TARGE SUNNYNOOK S Unsworth T T T S Forrest C Heights E O South & East Auckland R G Hill R L Totara Vale R D E A D R 1 R N AIRA O S Matapihi Point F W F U I T Motutapu E U R RD Stony Batter D L Milford Waitemata THE R B O D Island Thompsons Point Historic HI D EN AR KITCHENER RD Waihihi Harbour RE H Hakaimango Point Reserve G Greenhithe R R TRISTRAM Bayview D Kauri Point TAUHINU E Wairau P Korakorahi Point P DIANA DR Valley U IPATIKI CHIVALRY RD HILLSIDERD 1 A R CHARTWELL NZAF Herald K D Lake Takapuna SUNNYBRAE RD SHAKESPEARE RD ase RNZAF T Pupuke t Island 18 Glenfield AVE Takapuna A Auckland nle H Takapuna OCEAN VIEW RD kland a I Golf Course A hi R Beach Golf Course ro O ia PT T a E O Holiday Palm Beach L R HURSTMERE RD W IL D Park D V BEACH HAVEN RD NORTHCOTE R BAY RD R N Beach ARCHERS RD Rangitoto B S P I O B E K A S D A O D Island Haven I R R B R A I R K O L N U R CORONATION RD O E Blackpool H E Hillcrest R D A A K R T N Church Bay Y O B A SM K N D E N R S Birkdale I R G Surfdale MAN O’WA Hobsonville G A D R North Shore A D L K A D E Rangitawhiri Point D E Holiday Park LAK T R R N OCEANRALEIGH VIEW RD I R H E A R E PUPUKE Northcote Hauraki A 18 Y D EXMOUTH RD 2 E Scott Pt D RD L R JUTLAND RD E D A E ORAPIU RD RD S Birkenhead V I W K D E A Belmont W A R R K ONEWA L HaurakiMotorway . -

Attachment Manurewa Open Space Netw

Manurewa Open Space Network Plan August 2018 1 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Purpose of the network plan ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Strategic context .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.3 Manurewa Local Board area ............................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Current State ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 Treasure ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 Enjoy ................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Connect .............................................................................................................................................................. 22 -

Routes Manurewa Fare Zones & Boundaries Routes

Manurewa Routes Fare Zones 33 Papakura, Great South Rd, Manurewa, Manukau, Southern Bus Timetable Otahuhu Town Centre, Otahuhu Station & Boundaries 361 Manurewa, Clendon Park, Homai, Manukau, Tui Rd, Otara MIT North Campus Wellsford 362 Weymouth, Manurewa, Great South Rd, Manukau Station Omaha 363 Manurewa, Wattle Downs Matakana 365 Manukau Station, Homai, Manurewa, Randwick Park, Warkworth Takanini Station, Porchester Rd, Papakura Station 366 Manurewa, The Gardens, Everglade Dr, Manukau Station Warkworth Waiwera Helensville Hibiscus Coast Your guide to buses in this area Other timetables available in this area that may interest you Orewa Wainui Kaukapakapa Hibiscus Coast Gulf Harbour Timetable Routes Waitoki Mangere, Otahuhu, 31, 32, 309, 309X, 313, 321, 324, Upper North Shore Papatoetoe 25, 326, 380 Otara, Papatoetoe, Albany 31, 33, 314, 325, 351, 352, 353, 361 Waiheke Highbrook, East Tamaki Constellation Lower North Shore Riverhead Hauraki Gulf Takapuna Rangitoto Papakura 33, 365, 371, 372, 373, 376, 377, 378 Island 33 Huapai Westgate City Pukekohe, Waiuku Isthmus 391, 392, 393, 394, 395, 396, 398, 399 Waitemata Harbour Britomart Swanson Airporter 380 Kingsland Newmarket Beachlands Henderson Southern Line Train timetable Waitakere Panmure Eastern Line New Lynn Waitakere Onehunga 361 362 363 Ranges Otahuhu Botany Manukau Manukau Airport Manukau Harbour North Manukau South 365 366 Papakura Franklin Pukekohe Port Waikato Waiuku Tuakau Warkworth Huapai Manukau North Hibiscus Coast Waitakere Manukau South Upper North Shore City Franklin -

Manurewa Local Board Meeting Held on 5/12/2019

Work Programme 2019/2020 Q1 Report ID Activity Name Activity Description Lead Dept / Budget Budget Activity RAG Q1 Commentary Unit or CCO Source Status Arts, Community and Events 110 Manurewa Lifelong Enable Manurewa's growing number of residents aged 55 years and over CS: ACE: LDI: Opex $65,000 In progress Green The Manurewa Seniors Network meetings are on hold as the meetings have been Learning and Seniors to engage in community activities and access the Life Long Learning Community service provider-led rather than community-led by seniors, and have not been well Network Scholarship to apply for funds for lifelong learning opportunities. Empowerment attended. Strengthen the capacity and partnerships of the Manurewa Seniors Haumaru Housing was unable to meet all its deliverables and have returned their Network to deliver Manurewa Seniors Network Expo and Life Long unspent funding. Staff are engaging a local contractor to identify existing local Learning Fund for seniors in Manurewa. ($15k) seniors networks and groups, and isolated seniors in the local board area, to establish their needs, strengths and aspirations. Results of the project will be Fund Manurewa Business Association to deliver Shuttle Loop Service. available in Q2. ($50k) 111 Manurewa Youth Fund the Youth Council to be involved in building the capacity of young CS: ACE: LDI: Opex $72,000 In progress Green The Manurewa Rangatahi scholarship round will be open for interested applicants Council and Rangatahi people to shape plans, neighbourhood facilities, and encourage and Community by the end of Q1. The 2019/2020 application and criteria have been updated and Scholarships support youth-led activities, linking into placemaking activity in Manurewa. -

Part 3 New and Future Urban Expansion

PART 3 - CONTENTS PART 3 NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3 .1 INTRODUCTION 3.1 .1 General 3.1 .2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.3 New Urban Zoning 3. 1 .4 Future Development Zoning and Staging 3 . 1 . 5 Structure Plans 3.2 NEW DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVE AND POLICIES 3.3 CLENDON PARK 3.4 FLAT BUSH 3.5 BOTANY ROAD WEST 3 .6 HILL ROAD 3 .7 WOODSIDE HEIGHTS 3 .8 MANGEMANGEROA 3 .9 TE U KAIPO 3 .10 WESTNEY ROAD 3.11 MASSEY ROAD 3.12 ORUARANGI SOUTH CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 3 - NEW AND FUTURE URBAN EXPANSION 3.1 INTRODUCTION ( 3.1.1 General This part of the Scheme sets out the objectives and policies for the expansion of the City's urban area for the purpose of establishing the ultimate form of the City. An indication is given of the pattern and sequence in which development will occur and the means by which the releasing of land from rural to urban purposes will be implemented. Also included in this Part are structure plans for: Clendon Park Flat Bush Botany Road West Hill Road Woodside Heights Mangemangeroa Te U Kaipo Westney Road Massey Road Oruarangi South 3.1.2 Urban Development Strategy 3.1.2.1 Plan 3A gives an overview of Council's urban development strategy. The primary aim of the Council's future development policies is to achieve by way of controlled development the consolidation of the City in order to improve transport linkages and create a better relationship between home, work, shopping and recreational facilities. -

Auckland Web.Indd

LOCAL SERVICES REGIONAL SAME DAY SERVICES YOUR V..A NI. P N Refer to pick-up times below for region-wide services TO IDENTIFY YOUR PICK UP & DELIVERY AREA PLEASE USE THE FOLLOWING CHART: FOR YOUR INFORMATION L Cycle (times your courier is Customer Services Website out on the road) 1 2 3 4 5 CA V.A.N. Automated booking International Help Desk Your pick-up times Sales/Administration 09 526 3100 Local Fax 09 526 3120 LO Central (Penrose) only 6am-10.00am 10.30am-12.00pm 12.30pm-1.45pm 2.15pm-3.25pm 3.50pm-6pm City, West, East, South, 6am-9.30am 9.50am-11.20am 11.45am-1.05pm 1.30pm-2.50pm 3.15pm-6pm NORTH SHORE CITY EAST TAMAKI ALBANY (ALBANY ESTATE) CBD BOTANY DOWNS ARMY BAY EDEN TERRACE BUCKLANDS BEACH CKLAND BEACHAVEN EPSOM COCKLE BAY BELMONT FREEMANS BAY EAST TAMAKI BIRKDALE GRAFTON HALF MOON BAY AU BIRKENHEAD GREY LYNN HIGHLAND PARK BROWNS BAY HERNE BAY HOWICK CAMPBELLS BAY KINGSLAND MEADOWLANDS CASTOR BAY KOHIMARAMA PAKURANGA DEVONPORT MISSION BAY FORREST HILL MORNINGSIDE SOUTH AUCKLAND GLENFIELD MT ALBERT AIRPORT (INTERNATIONAL GULF HARBOUR MT EDEN & DOMESTIC) AIRPORT OAKS HERALD ISLAND MT ROSKILL CONIFER GROVE HOBSONVILLE NEWMARKET DRURY MAIRANGI BAY NEWTON MANGERE MILFORD ORAKEI MANGERE EAST MURRAYS BAY PARNELL MANUKAU NORTH HARBOUR ESTATE PONSONBY MANUREWA NORTHCOTE REMUERA MERCER OREWA SANDRINGHAM OTARA RED BEACH ST HELIERS PAPAKURA ROTHESAY BAY VICTORIA PARK MARKET PAPATOETOE SILVERDALE WESTERN SPRINGS POKENO SUNNYNOOK WESTHAVEN PUKEKOHE TAKAPUNA RAMARAMA TORBAY CENTRAL (PENROSE) TAKANINI WEST HARBOUR ELLERSLIE WATTLE DOWNS WHANGAPARAOA EPSOM WEYMOUTH WHENUAPAI GLEN INNES GLENDOWIE WHITFORD WEST AUCKLAND GREENLANE AVONDALE TE ATATU HILLSBOROUGH BLOCKHOUSE BAY TITIRANGI MEADOWBANK GLEN EDEN WATERVIEW MT ROSKILL GLENDENE MT WELLINGTON h GREEN BAY ONE TREE HILL HENDERSON ONEHUNGA HILLSBOROUGH OTAHUHU KELSTON OWAIRAKA DELIVERY STANDARD LINCOLN PANMURE MT ALBERT PENROSE (not including residential) NEW LYNN REMUERA Every reasonable attempt will be made to POINT CHEVALIER ST HELIERS deliver within your area: next cycle. -

Part 2 the City: Present and Future Trends

• PART 2 - CONTENTS PART 2 THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2. 1 THE FORM OF THE CITY 2.2 GROWTH OF THE CITY 2.3 ETHNIC ORIGIN OF POPULATION 2.4 EMPLOYMENT 2.5 BUILDING DEVELOPMENT AND DEMAND 2.6 TRANSPORTATION AND LAND USE 2.7 FUTURE URBAN GROWTH 2.8 LAND PRESENTLY ZONED FOR URBAN USES 2.9 RURAL LAND USE 2.10 CONTEXT OF THE PLANNING SCHEME CITY OF MANUKAU SECOND REVIEW PART 2 - THE CITY: PRESENT AND FUTURE TRENDS 2.1 THE FORM OF THE CITY Manukau City had a population in March 1986 of 177,248. Its land area of over 600 square kilometres dominates the southern part of the Auckland Region. The territorial integrity of the district, stretches from the edge of the Auckland isthmus in the north to the Hunua Ranges in the south. The Manukau City Centre, 25 km south of Auckland Centre, is the natural geographical focus of the city's urban area. When fully developed the urban area will stretch out from the Centre southwards to Manurewa, northeastwards to Otara and Pakuranga and northwest to Mangere. Two-thirds of the City's land area is in rural use, ranging from dairy and town milk supply units to pastoral farming, horticulture and forestry. A distinctive feature of the district is its extensive coastline of 320 km. In the west is the Manukau Harbour, from which the City takes its name. In the east is the Hauraki Gulf and in the north the Tamaki River. Residential development in the urban part of the City has taken full advantage of the coastline. -

'Everything Is Community': Developer and Incoming Resident Experiences

‘Everything is community’: Developer and incoming resident experiences of the establishment phase at Waimahia Inlet Emma Fergussona, Karen Wittena, Robin Kearnsb, Liam Kearnsb October 2016 aMassey University bUniversity of Auckland Residential Choice and Community Formation Strand Resilient Urban Futures Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 CONTEXT 4 METHODS 4 FINDINGS 5 CONCLUSIONS 7 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1. THE SITE 9 1.2. POLITICAL CONTEXT 11 1.2.1 Auckland’s housing ‘crisis’ 11 1.2.2 Social housing reform 12 1.3. WEYMOUTH DEMOGRAPHICS 14 1.4. CASE STUDY RESEARCH CONTEXT: RESILIENT URBAN FUTURES 14 2. HOUSING DEVELOPMENTS AND THE THIRD SECTOR 15 2.1. HOUSING TRANSFER AND THE THIRD SECTOR 15 2.2. SOCIAL MIX AND TENURE MIX 17 3. METHODS 18 4. FINDINGS: DEVELOPER EXPERIENCE 20 4.1. ORIGINS OF THE DEVELOPMENT: COLLABORATION AND NEGOTIATION 20 4.2. STRUCTURE OF THE CONSORTIUM 22 4.3. VALUES, PRIORITIES AND STRENGTHS 23 4.4. DECISION-MAKING 24 4.5. EXISTING WEYMOUTH COMMUNITY 25 4.6. THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT 26 4.6.1. Central government 26 4.6.2. Local government 27 4.7. FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES AND STATE HOUSING TRANSFER 28 4.8. DISCUSSION 29 5. FINDINGS: INCOMING RESIDENT EXPERIENCE 31 5.1. THE PARTICIPANTS 31 5.2. FINDING OUT ABOUT WAIMAHIA INLET 31 5.3. MOTIVATIONS FOR MOVING 32 5.3.1. Community Housing Provider tenants: affordability and security 32 5.3.2. Owner-occupiers: affordability, opportunity, community 33 5.4. THE EARLY STAGES: INTERACTIONS WITH TMCHL AND CHPS 35 5.4.1. Community Housing Provider rental tenants 36 5.4.2. -

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1

Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 1 Chapter 6 — Heritage CONTENTS This chapter is presented as follows: 6.1 Introduction This outlines how heritage is defined and the statutory context of this chapter. 6.2 Resource Management Issues This outlines the significant resource management issues relating to heritage resources within the City. 6.3 Objectives This sets out the overall desired environmental outcomes for the heritage resources of the City. 6.4 Policies This describes how Council intends to ensure that the objectives for the City’s heritage resources are met. An explanation of the policies is given. A summary of the range of methods that are used to implement each policy is also included. 6.5 Heritage Strategy The strategy summarises the overall approach to managing the City’s natural and cultural heritage resources. 6.6 Implementation This broadly describes the regulatory and non-regulatory methods used to implement the policies for the management of the City’s heritage resources. 6.7 Anticipated Environmental Results This outlines the environmental outcomes anticipated from the implementation of the policies and methods as set out in the Heritage Chapter. 6.8 Procedures for Monitoring This outlines how Council will monitor the effectiveness of the Heritage provisions. Manukau Operative District Plan 2002 Chapter 6 — Heritage Page 2 6.9 Rules — Activities This sets out in an Activity Table the permitted and discretionary activities for the scheduled heritage resources of the City. 6.10 Rules – Matters for Control: Controlled Activities 6.11