“The Good People of Newburgh”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relocation Assistance Program Survey

CUY - OPPORTUNITY CORRIDOR PID 77333 PLAN DEVELOPMENT PROCESS MAJOR STEP 7 (FINAL ALIGNMENT) RELOCATION ASSISTANCE PROGRAM SURVEY Prepared for: HNTB Ohio, Inc. on behalf of the Ohio Department of Transportation District 12 Prepared by: September 15, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ i 2.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Project Scope .................................................................................................................... 2 3.0 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................. 3 3.1 Supplemental Housing Benefits ........................................................................................ 3 3.2 Moving Allowance Payments ........................................................................................... 4 3.3 Non-Residential Move, Search & Re-Establishment Payments ....................................... 5 3.3(A) Loss of Goodwill and Economic Loss .............................................................................. 5 3.4 Field Survey ...................................................................................................................... 7 3.5 Estimated Acquisition Costs ............................................................................................. 7 3.6 Available Housing ........................................................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

.NFS Form. 10-900-b ,, .... .... , ...... 0MB No 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) . ...- United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________ Historic and Architectural Resources of the lower Prospect/Huron _____District of Cleveland, Ohio________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Commercial Development of Downtown Cleveland, C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, bounded approximately by Ontario Street, Huron Road NW, and West 9th Street on the west; Lake Brie on the north; and the Innerbelt Jreeway on the east and south* I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in>36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. 2-3-93 _____ Signature of certifying official Date Ohio Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

CMA Landscape Master Plan

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN DECEMBER 2018 LANDSCAPE MASTER PLAN The rehabilitation of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s grounds requires the creativity, collaboration, and commitment of many talents, with contributions from the design team, project stakeholders, and the grounds’ existing and intended users. Throughout the planning process, all have agreed, without question, that the Fine Arts Garden is at once a work of landscape art, a treasured Cleveland landmark, and an indispensable community asset. But the landscape is also a complex organism—one that requires the balance of public use with consistency and harmony of expression. We also understand that a successful modern public space must provide more than mere ceremonial or psychological benefits. To satisfy the CMA’s strategic planning goals and to fulfill the expectations of contemporary users, the museum grounds should also accommodate as varied a mix of activities as possible. We see our charge as remaining faithful to the spirit of the gardens’ original aesthetic intentions while simultaneously magnifying the rehabilitation, ecological health, activation, and accessibility of the grounds, together with critical comprehensive maintenance. This plan is intended to be both practical and aspirational, a great forward thrust for the benefit of all the people forever. 0' 50' 100' 200' 2 The Cleveland Museum of Art Landscape Master Plan 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CMA Landscape Master Plan Committee Consultants William Griswold Director and President Sasaki Heather Lemonedes -

University Neighborhood Plan Summary

UNIVERSITY NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN SUMMARY Description. The University neighborhood encompasses two of Cleveland’s most well known places, University Circle and Little Italy. University Circle came into being in the 1880s with the donation of 63 acres of wooded parkland to the City by financier Jeptha Wade, one of the creators of Western Union. “Little Italy.” was established in the late 1800s by Italian immigrants who settled there for lucrative employment in the nearby marble works. The dense housing in Little Italy represents the largest residential area in the neighborhood. There are a few other isolated streets of residential and student housing located in the neighborhood. The majority of the land in the neighborhood is either institutional use or park land. Assets. University is home to many institutions that are not only assets to the neighborhood but the region as well. Among the assets in the neighborhood are: • educational institutions like Case Western Reserve University, the Cleveland Institute of Art, the Cleveland Institute of Music, the Cleveland Music School Settlement, John Hay High School and the Arts Magnet School • health institutions the University Hospitals and the Veterans Hospital • cultural attractions such as the Cleveland Museum of Art, Severance Hall, the Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Children’s Museum and the Cleveland Botanical Gardens • natural features such as Doan Brook and the hillside to the “Heights” • open spaces such as Wade Park, Ambler Park and Lakeview Cemetery -

University Farm Squire Valleevue and Valley Ridge Farms

University Farm Squire Valleevue and Valley Ridge Farms Annual Report 2009 Research education conservation preservation 39 OPERATIONS AND FINANCES 2 ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH PROGRAMS 4 CONSERVATION PROGRAMS AND GREEN INITIATIVES 14 STUDENT LIFE 18 FACILITIES USAGE 22 COMMUNITY SERVICE 24 GRANTS AND GIFTS 26 MAJOR IMPROVEMENTS AND REPAIRS 28 Statistics 32 36 The Case Western Reserve University as a farm for educational purposes, and to be Farm, located on Fairmount Boulevard in The a place where the practical duties of life may be Village of Hunting Valley, is a 389-acre property taught; where the teachers and students can that includes forests, ravines, waterfalls, come in close contact with Mother Earth.” meadows, ponds, a self-contained natural The Wade gift was made with the intent that watershed, seven residences, many other “the premises ... be preserved in an open structures and several miles of roads and trails. and undeveloped state subject to reasonable The farm came to the university as the result provisions for access ... and the premises of four gifts. The late Andrew Squire gave 277 may be used for investigation, research and acres (Squire Valleevue Farm) in the late 1930s; teaching in all fields relating to the natural in 1977, the heirs of Jeptha Wade II gave Case sciences and the ecology of natural systems, Western Reserve 104 adjoining acres (Valley including man’s use of said systems through Ridge Farm); in 1984, John and Elizabeth agriculture, aquaculture and otherwise.” As Hollister deeded five acres to the university; a condition of this gift, the university officers and in 1995, the Hollisters donated another five report annually to the Board of Trustees of the acres. -

Heritage of Books on Cleveland

A L....--_----' Heritage of Books on Cleveland Cleveland Heritage Program A HERITAGE OF BOOKS: A Selected Bibliography of Books and Related Materials on Cleveland to be found at the Cleveland Public Library by Matthew F. Browarek CLEVELAND PUBLIC LIBRARY 1984 Cover photograph: Hiram House Station C 1920 Archives. Cleveland Public Library PREFACE The Cleveland Heritage Program was born out of the conviction that the city of Cleve land possesses unique qualities worth capturing in pictures and words. In designing the program, Professor Thomas Campbell of Cleveland State University and I were prompted less by a desire to evoke nostalgia than to retrieve fugitive material for the benefit of scholars whose work will help us to understand how and why our city is what it is. If the uses of history are to serve the present generation, then the Cleveland Heritage Program has done its work well. Funded primarily by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the program was carried on over a two-year period from 1981 to 1983. Important supple mentary grants were made by the Cleveland Foundation, the George Gund Foundation and Nathan L. Dauby Fund. Also, the Cleveland Heritage Program greatly benefited from the cooperation of the following institutions: the Cleveland Public Schools, the Catholic Diocese of Cleveland, the Greater Cleveland Growth Association, the Western Reserve Historical Society, Cuyahoga Community College, WVIZ-TV and the College of Urban Affairs of Cleveland State University. Under Professor Campbell and his many able assistants, diligent research recovered valuable artifacts, photographs and oral histories relating to several of Cleveland's neigh borhoods. -

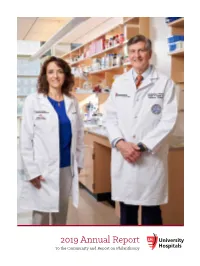

2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy

2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy Cover: Leading UH research on COVID-19, Grace McComsey, MD, Vice President of Research and Associate Chief Scientific Officer, UH Clinical Research Center, Rainbow Babies & Children's Foundation John Kennell Chair of Excellence in Pediatrics, and Division Chief of Infectious Diseases, UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital; and Robert Salata, MD, Chairman, Department of Medicine, STERIS Chair of Excellence in Medicine and and Master Clinician in Infectious Disease, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and Program Director, UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine and Global Health, are Advancing the Science of Health and the Art of Compassion. Photo by Roger Mastroianni The 2019 UH Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy includes photographs obtained before Ohio's statewide COVID-19 mask mandate. INTRODUCTION REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY 5 Letter to Friends 38 Letter to our Supporters 6 UH Statistics 39 A Gift for the Children 8 UH Recognition 40 Honoring the Philanthropic Spirit 41 Samuel Mather Society UH VISION IN ACTION 42 Benefactor Society 10 Building the Future of Health Care 43 Revolutionizing Men's Health 12 Defining the Future of Heart and Vascular Care 44 Improving Global Health 14 A Healing Environment for Children with Cancer 45 A New Game Plan for Sports Medicine 16 UH Community Highlights 48 2019 Endowed Positions 18 Expanding the Impact of Integrative Health 54 Annual Society 19 Beating Cancer with UH Seidman 62 Paying It Forward 20 UH Nurses: Advancing and Evolving Patient Care 63 Diamond Legacy Society 22 Taking Care of the Browns. -

Ohio & Erie Canalway: Connectivity, Community, Culture

2 0 1 1 OHIO & ERIE CANALWAY: CONNECTIVITY, COMMUNITY, CULTURE OHIO & ERIE CANALWAY: CONNECTIVITY, COMMUNITY, CULTURE Prepared by the 2011 Maxine Levin College of Urban Affairs Planning Capstone Studio class under the direction of Dr. Sugie Lee, Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University and Mr. James Kastelic, Senior Park Planner, Cleveland Metroparks. Class Members Jonathan Baughman Hannah Belsito Richard Burns Cassandra Gaffney Stephen Gage Katherine Kowalczyk Zachary Mau Tanja McCoy Michael McGarry Kimberly Merik Delilah Onofrey Trevor Rutti Coral Troxell Sherry Tulk John Vitou OHIO & ERIE CANALWAY: CONNECTIVITY, COMMUNITY, CULTURE T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 BOUNDARY & ORGANIZATIONAL LANDSCAPE 3 IMPACT ANALYSIS 9 STRATEGIC PLAN 59 MARKETING & TOURISM PROPOSAL 111 CONCLUSION 125 APPENDIX & REFERENCES 126 OHIO & ERIE CANALWAY: CONNECTIVITY, COMMUNITY, CULTURE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This comprehensive document is Cleveland State University‘s Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs, Master of Urban Planning, Design & Development Capstone Class of 2011‘s, compilation of research, analysis and recommendations for the Ohio & Erie Canalway National Heritage Area. As a group we examined the Heritage Area from conception, designation, progressive establishment and growth and provide our resulting vision and strategic recommendations to expand and propel the corridor to greater capacity of enhancement, success and regionalization. The accomplishments of the Ohio & Erie Canalway Association, Ohio Canal Corridor and Ohio & Erie Canalway Coalition, (Canalway Organizations), various other entities, visioning partners and ensuing forged partnerships are numerous and inspiring. These partners are leading the Heritage Area to establish a renewed identity, to regeneration of Northeast Ohio cities and towns and proliferation of the tourism industry, utilizing the canal legacy of regional and national prominence. -

PDF of Article Is Here

CLEVELAND: ECONOMICS, IMAGES, AND EXPECTATIONS JOHN J. GRABOWSKI INTRODUCTION hy do cities grow, thrive, and sometimes fail? What holds them together Wand makes them special places—unique urban landscapes with distinctive personalities? Often we fix on the “image” of a city: its structural landmarks; the natural environment in which it is situated, or the amenities of life which give it character, be they an orchestra or a sports team. Even less tangible attributes, including a reputation for qualities such as innovation, perseverance, or social justice, come into play here. Image, however, is often a gloss, one that hides the core of the community, the portion of its history that has been central to its exis- tence. Many would like to see Cleveland, both now and historically, as a “city on a hill,” one defined by many of the factors noted above. Yet, Cleveland’s image is to an extent a veneer. Underneath that veneer is the economic core that led to the creation of the city and that has sustained it at various levels for over 200 years. Without it, the veneer would not exist. The fact that today, aspects of Cleveland’s veneer have merged into its economic core represents a remarkable historical transformation. Cleveland’s Public Square is perhaps the best place to begin in examining the history of Cleveland and the interrelationship between economic reality and image. On the northwest quadrant of the square a statue of Tom L. Johnson re- minds one and all that Cleveland was in the forefront of the Progressive move- ment at the turn of the twentieth century. -

History of Cleveland State University

History of Cleveland State University Established as a state-assisted university in 1964, Cleveland State University was created out of the buildings, faculty, staff, and curriculum of the former Fenn College, a private institution of 2,500 students that was founded in 1929. Cleveland State University’s historical roots go back to the 19th century. During the 1880s, the Cleveland YMCA began to offer day and evening courses to students who did not otherwise have access to higher education. The YMCA program was reorganized in 1906 as the Association Institute, and this in turn was established as Fenn College in 1929. A significant contribution of Fenn College was its pioneering work in developing internships for students in engineering and business. These internships, as joint ventures between the college and local businesses and industries, provided students with professional contacts and experience, as well as an affordable education. The historic Fenn Tower still stands as a reminder of those early years, when the University already had a strong commitment to equal access to higher education. The Cleveland-Marshall College of Law traces its origins to 1897 when the Cleveland Law School was founded. It was the first evening law school in the state and one of the first to admit women and minorities. Another evening law school, John Marshall School of Law, was founded in 1916. In 1946, the two schools merged to become the Cleveland- Marshall School of Law. Cleveland-Marshall became part of Cleveland State University in 1969. 10 Profile of Cleveland State University Cleveland State University: New Attitudes, New Experiences, New Outlooks A Campus Rich in Tradition Cleveland State was established as a state university in 1964 and has continued to grow since. -

Master Plan Final

Adopted March 20, 2017 CITY OF CLEVELAND HEIGHTS MASTER PLAN City of Cleveland Heights 40 Severance Circle Cleveland Heights, Ohio 44118 216.291.4444 www.ClevelandHeights.com Cuyahoga County Planning Commission 2079 East 9th Street Suite 5-300 Cleveland, OH 44115 216.443.3700 www.CountyPlanning.us www.facebook.com/CountyPlanning www.twitter.com/CountyPlanning About County Planning The Cuyahoga County Planning Commission’s mission is to inform and provide services in support of the short and long term comprehensive planning, quality of life, environment, and economic develop- ment of Cuyahoga County and its cities, villages and townships. Planning Team Alison Ball, Planner Rachel Culley, Planning Intern Meghan Chaney, AICP, Senior Planner Ryan Dyson, Planning Intern Glenn Coyne, FAICP, Executive Director Travis Gysegem, Planning Intern Patrick Hewitt, AICP, Senior Planner Olivia Helander, Planning Intern Dan Meaney, GISP, Manager, Information and Research Jesse Urbancsik, Planning Intern James Sonnhalter, Manager, Planning Services Micah Stryker, AICP, Planner Robin Watkins, Geographic Information Systems Specialist Front Image Source: City of Cleveland Heights CITY OF CLEVELAND HEIGHTS MASTER PLAN City of Cleveland Heights 40 Severance Circle Cleveland Heights, Ohio 44118 216.291.4444 www.ClevelandHeights.com 2016 City Council Members Cheryl L. Stephens, Mayor Kahlil Seren, Councilperson Jason S. Stein, Vice Mayor Michael Ungar , Councilperson Carol Roe, Councilperson Melissa Yasinow, Councilperson Mary A. Dunbar, Councilperson 2015 City -

From Exhibition to Conversation: the Elusive Art of Digital Storytelling

From Exhibition to Conversation: The Elusive Art of Digital Storytelling Keynote presentation at Network Detroit 2016 Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, September 30, 2016 J. Mark Souther Professor of History and Director, Center for Public History + Digital Humanities Cleveland State University For several decades in the 19th and early 20th centuries, Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue was known as “Millionaires’ Row” and even “The Showplace of America.” Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller, arc lamp inventor Charles Brush, Western Union founder Jeptha Wade, and many other luminaries called the thoroughfare home. But nearly all of their baronial mansions met the wrecking ball as Cleveland rose to the status of America’s “Fifth City” (right behind Detroit). Euclid Avenue’s downtown section became a celebrated shopping street—the nation’s sixth largest—with six major department stores, an echo of Chicago’s State Street. That too had completely disappeared by the 1990s. Perhaps the only bright spots along the entire six-mile corridor were Playhouse Square, a warren of interconnected theaters from the 1920s that were reopened after the nation’s largest theater restoration project, and University Circle, a collective campus housing the city’s major museums and “eds- meds” institutions. Most of the rest was a shell of what it was a century before. Then, in 2005, I had the opportunity to work with a colleague and our students on a place-making project that focused on the history of Euclid Avenue—Cleveland’s answer to Woodward Avenue. The city’s transit authority was building a busway on Euclid with a federal grant that had a 1% earmark for the arts.