A City of Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Kenneth J

2006 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Kenneth J. Wright, PE Thomas G. Leech, PE, SE HDR Engineering, Inc. Gannett Fleming, Inc. General Chair Magazine Chair M. Myint Lwin, PE, SE Herbert M. Mandel, PE Federal Highway GAI Consultants, Inc. Administration Technical Program Chair Matthew P. McTish, PE McTish, Kunkel & Associates Al M. Ahmed, PE Exhibits Chair A&A Consultants Inc. Gerald Pitzer, PE Michael J. Alterio GAI Consultants, Inc. Alpha Structures Inc. Gary Runco, PE Carl Angeloff, PE Paul C. Rizzo Associates, Inc. Bayer MaterialScience, LLC Seminars Chair Awards Chair Helena Russell Victor E. Bertolina, PE Bridge, design & engineering SAI Consulting Engineers Awards – Vice Chair Budget Chair Louis J. Ruzzi, PE Enrico T. Bruschi, PE Pennsylvania Department DMJM Harris of Transportation Jeffrey J. Campbell, PE Thomas J. Vena, PE Michael Baker, Jr., Inc. Allegheny County Department of Public Works Richard Connors, PE, PMP McCormick Taylor, Inc. Lisle E. Williams, PE, PLS Rules Chair DMJM Harris Attendance & Co-Sponsors James D. Dwyer Chair STV, Inc. Emeritus Committee Gary L. Graham, PE Members Pennsylvania Turnpike Joel Abrams, PhD Commission Consultant Kent A. Harries, PhD, PEng Reidar Bjorhovde, PhD University of Pittsburgh The Bjorhovde Group Student Awards Chair Steven Fenves, PhD Donald W. Herbert, PE NIST Pennsylvania Department of Transportation Arthur W. Hedgren, Jr., PhD, PE Donald Killmeyer, Jr., PE Consultant ms consultants, inc. Tour Chair John F. Graham, Jr., PE Graham Consulting Inc. Eric S. Kline KTA-Tator, Inc. Keynote & Special Interest Session Chair ADVANCING BRIDGE TECHNOLOGY GLOBALLY ○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ 1 2006 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Kenneth J. Wright, PE HDR Engineering, Inc. 2006 IBC General Chairman As this year’s General Chairman, I am pleased to wel- come you to the 2006 International Bridge Conference in Pittsburgh, the “City of Bridges”. -

“Hello, Dolly!” the Tony Award-Winning Be

FOR RELEASE ON JULY 23, 2018 “The best show of the year. ‘Hello, Dolly!’ must not be missed.” NPR, David Richardson “This ‘Dolly!’ is classic Broadway at its best.” Entertainment Weekly, Maya Stanton “It is, in a word, perfection.” Time Out New York, Adam Feldman TONY AWARD®-WINNING BROADWAY LEGEND BETTY BUCKLEY STARS IN FIRST NATIONAL TOUR OF “HELLO, DOLLY!” THE TONY AWARD-WINNING BEST MUSICAL REVIVAL WILL BEGIN PERFORMANCES SEPTEMBER 30 AT PLAYHOUSE SQUARE SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE JULY 27 Cleveland, OH – The producers of HELLO, DOLLY!, the Tony Award-winning Best Musical Revival, and Playhouse Square announced today that single tickets for the National Tour starring Broadway legend Betty Buckley will go on sale Friday, July 27. Tickets will be available at the Playhouse Square Ticket Office (1519 Euclid Avenue in downtown Cleveland), by visiting playhousesquare.org, or by calling 216-241-6000. Group orders of 15 or more may be placed by calling 216-640-8600. HELLO, DOLLY! comes to Playhouse Square September 30 through October 21, 2018 as part of the KeyBank Broadway Series. Tony Award-winning Broadway legend Betty Buckley stars in HELLO, DOLLY! – the universally acclaimed smash that NPR calls “the best show of the year!” and the Los Angeles Times says “distills the mood-elevating properties of the American musical at its giddy best.” Winner of four Tony Awards including Best Musical Revival, director Jerry Zaks’ “gorgeous” new production (Vogue) is “making people crazy happy!” (The Washington Post). Breaking box office records week after week and receiving unanimous raves on Broadway, this HELLO, DOLLY! pays tribute to the original work of legendary director/choreographer Gower Champion – hailed both then and now as one of the greatest stagings in musical theater history. -

The Cuyahoga River Area of Concern

OHIO SEA GRANT AND STONE LABORATORY The Cuyahoga River Area of Concern Scott D. Hardy, PhD Extension Educator What is an Area of Concern? 614-247-6266 Phone reas of Concern, or AOCs, are places within the Great Lakes region where human 614-292-4364 Fax [email protected] activities have caused serious damage to the environment, to the point that fish populations and other aquatic species are harmed and traditional uses of the land Aand water are negatively affected or impossible. Within the Great Lakes, 43 AOCs have been designated and federal and state agencies, under the supervision of local advisory committees, are working to clean up the polluted sites. Ohio Sea Grant Cuyahoga River AOC College Program Who determines if there 1314 Kinnear Rd. is an Area of Concern? Columbus, OH 43212 614-292-8949 Office A binational agreement between the United States 614-292-4364 Fax and Canada called the Great Lakes Water Quality ohioseagrant.osu.edu Agreement (GLWQA) determines the locations Ohio Sea Grant, based at of AOCs throughout the Great Lakes. According The Ohio State University, to the GLWQA, each of the AOCs must develop is one of 33 state programs in the National Sea Grant a Remedial Action Plan (RAP) that identifies all College Program of the of the environmental problems (called Beneficial National Oceanic and Use Impairments, or BUIs) and their causes. Local Atmospheric Administration environmental protection agencies must then (NOAA), Department of develop restoration strategies and implement them, Commerce. Ohio Sea Grant is supported by the Ohio monitor the effectiveness of the restoration projects Board of Regents, Ohio and ultimately show that the area has been restored. -

Annual Events 2019 Calendar

Annual events 2019 Calendar Seasonal Events September-December March September 2018 – June 2019 NFL Cleveland Browns Regular Season 3/2: Cleveland Kurentovanje FirstEnergy Stadium, Various locations, St. Clair-Superior The Cleveland Orchestra at Downtown Cleveland neighborhood Severance Hall www.clevelandbrowns.com www.clevelandkurentovanje.com University Circle www.clevelandorchestra.com November-December 3/8-10: Wizard World Comic Con Huntington Convention Center of October 2018 – April 2019 Black Nativity at Karamu House Cleveland, Downtown Cleveland Karamu House, Fairfax wizardworld.com/comiccon/cleveland NBA Cleveland Cavaliers karamuhouse.org Regular Season 3/13-16: MAC Men’s & Women’s Quicken Loans Arena, November-January Basketball Tournament Downtown Cleveland GLOW at Cleveland Botanical Garden Quicken Loans Arena, www.cavs.com Cleveland Botanical Garden, Downtown Cleveland getsomemaction.com AHL Cleveland Monsters University Circle www.cbgarden.org Regular Season 3/17: St. Patrick’s Day Parade Quicken Loans Arena, Various locations, Downtown Cleveland Downtown Cleveland Events by Month www.stpatricksdaycleveland.com www.clevelandmonsters.com 3/20-24: Be A Tourist in April-September January Your Hometown Various locations MLB Cleveland Indians Regular Season 1/17-21: Cleveland Boat Show VisitMeInCLE.com Progressive Field, Downtown Cleveland I-X Center, West Park www.indians.com www.clevelandboatshow.com 3/27-4/7: Cleveland International MiLB Akron RubberDucks Film Festival 1/20: Martin Luther King, Jr. Tower City Cinemas, Regular -

Cuyahoga County Urban Tree Canopy Assessment Update 2019

Cuyahoga County Urban Tree Canopy Assessment Update 2019 December 12, 2019 CUYAHOGA COUNTY URBAN TREE CANOPY ASSESSMENT \\ 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Why Tree Canopy is Important 03 Project Background 03 Key Terms 04 Land Cover Methodology 05 Tree Canopy Metrics Methodology 06 Countywide Findings 09 Local Communities 14 Cleveland Neighborhoods 18 Subwatersheds 22 Land Use 25 Rights-of-Way 28 Conclusions 29 Additional Information PREPARED BY CUYAHOGA COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION Daniel Meaney, GISP - Information & Research Manager Shawn Leininger, AICP - Executive Director 2079 East 9th Street Susan Infeld - Special Initiatives Manager Suite 5-300 Kevin Leeson - Planner Cleveland, OH 44115 Robin Watkins - GIS Specialist Ryland West - Planning Intern 216.443.3700 www.CountyPlanning.us www.facebook.com/CountyPlanning www.twitter.com/CountyPlanning 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CUYAHOGA COUNTY URBAN TREE CANOPY ASSESSMENT \\ 2019 Why Tree Canopy is Important Tree canopy is the layer of leaves, branches, and stems of trees that cover the ground when viewed from above. Tree canopy provides many benefits to society including moderating climate, reducing building energy use and atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), improving air and water quality, mitigating rainfall runoff and flooding, enhancing human health and social well-being and lowering noise impacts (Nowak and Dwyer, 2007). It provides wildlife habitat, enhances property values, and has aesthetic impacts to an environment. Establishing a tree canopy goal is crucial for communities seeking to improve their natural environment and green infrastructure. A tree canopy assessment is the first step in this goal setting process, showing the amount of tree canopy currently present as well as the amount that could theoretically be established. -

Playhouse Square Donor Recognition

Playhouse Square Donor Recognition ith sincere gratitude, we recognize the following individuals, organizations, and foundations, who Whave provided generous support of $300 or higher to Playhouse Square through an annual or special gift. Listing current as of 5/20/19. Individuals & The Char & Chuck Fowler Family Alex & Kelly Clarke Terry Kovel Family Foundations Foundation Mr. & Mrs. Robert T. Clutterbuck Charles & Carleen Kruger Uleto & Lisa Fuentes Kenneth, Karen & Zoe Conley Edward & Jacque Largent President James Graham & David Dusek Jim & Mary Conway Steffen & Paige Lauster ($50,000 and higher) Rochelle & Harley Gross Mr. & Mrs. William E. Conway William B. & Mary Margaret Kathy & Jim Pender and the David & Robin Gunning Natalie & Paul Cooper Lawrence Michael Pender Fund of the Kathleen E. Hancock Bill & Paula Cosgrove Michele & Bob Lee Cleveland Foundation Marsha Ann Harrison Drs. Jay Costantini & Lisa Gelles Heather Lennox & Douglas Krause Bruce & Donna Jackson Daniel & Darlene Crudele Dean & Lynda Leonakis Director Judith S. Kamm Marti & Jeffrey Davis Edmund & Laura Leopold ($25,000 - $49,999) Catherine L. Lozick Veronica & Jesse Dickerson Dr. Edith Lerner Patricia & John Chapman David Maltz Jason & Jennifer Drasner Cathy & John Lewis Mr. Dennis & Dr. Tammy Matecun John & Mary Ann Mastrantoni Mike & Geri Evans Jan Lewis Mark & Shelly Saltzman Jim & Amy Merlino Bill Fenoglio & Erika Battaglia Carolyn Lincoln D. V. M. Morton J. Weisberg Brock Milstein Beverly Fittipaldo Joyce & Bill Litzler Beth E. Mooney The Fortney Family Foundation Jay & Lanee Lucarelli Executive Creighton & Janice Smith Murch Harry K. & Emma R. Fox Rita & Charles Maimbourg ($20,000 - $24,999) Jane & Jon Outcalt Charitable Foundation Paul & Corene Mancino A.J. & Tricia Hyland Louis B. -

CSU Student Eastside Parks Study

EASTSIDE PARKS Connection | Activation | Community Presented by: TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Project Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 I. Study Area Background ............................................................................................................................................... 6 II. Community Engagement, Project Focus, & Essential Tasks ................................................................................... 20 III. Plan ........................................................................................................................................................................... 29 IV. Implementatoin ...................................................................................................................................................... 88 V. References .............................................................................................................................................................. 90 VI. Appendices ............................................................................................................................................................. 94 ii Eastside Parks |Connection | Activation | Community I. PROJECT INTRODUCTION Project Background East Side Parks is the centerpiece of the 2020 Planning Studio course offered by the Levin College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland State University, for its Master of Urban Planning -

Program Booklet

The Irish Garden Club Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Murphy Irish Arts Association Proud Sponsors of the Irish Cultural Garden Celebrate One World Day 2019 Italian Cultural Garden CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (TRI-C®) SALUTES CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION’S ONE WORLD DAY 2019 PEACE THROUGH MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THANK YOU for 74 years celebrating Cleveland’s history and ethnic diversity The Italian Cultural Garden was dedicated in 1930 “as tri-c.edu a symbol of Italian culture to American democracy.” 216-987-6000 Love of Beauty is Taste - The Creation of Beauty is Art 19-0830 216-916-7780 • 990 East Blvd. Cleveland, OH 44108 The Ukrainian Cultural Garden with the support of Cleveland Selfreliance Federal Credit Union celebrates 28 years of Ukrainian independence and One World Day 2019 CZECH CULTURAL GARDEN 880 East Blvd. - south of St. Clair The Czech Garden is now sponsored by The Garden features many statues including composers Dvorak and Smetana, bishop and Sokol Greater educator Komensky – known as the “father of Cleveland modern education”, and statue of T.G. Masaryk founder and first president of Czechoslovakia. The More information at statues were made by Frank Jirouch, a Cleveland czechculturalgarden born sculptor of Czech descent. Many thanks to the Victor Ptak family for financial support! .webs.com DANK—Cleveland & The German Garden Cultural Foundation of Cleveland Welcome all of the One World Day visitors to the German Garden of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens The German American National congress, also known as DANK (Deutsch Amerikan- ischer National Kongress), is the largest organization of Americans of Germanic descent. -

The Important Resources Along the Corridor Include Not Only The

2 The Canal and its Region he important resources along the Corridor include not only the remains of the Ohio & TErie Canal and buildings related to it, but also patterns of urban and rural development that were directly influenced by the opportunities and ini- tiatives that were prompted by its success. These cul- tural landscapes—ranging from canal villages to community-defining industries to important region- al parks and open spaces—incorporate hundreds of sites on the National Register of Historic Places, rep- resenting a rich tapestry of cultural, economic, and ethnic life that is characteristic of the region's history Casey Batule, Cleveland Metroparks and future. Implementation of the Plan can protect and enhance these resources, using them effectively to improve the quality of life across the region. 16 Background Photo: Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area/NPS Ohio's historic Canal system opened the state for interstate commerce in the early 1800s. The American Canal and Transportation Center The American Canal and Transportation 2.1 National Importance of the Canal and Corridor The Imprint of the Canal Transportation Corridors on the Economy and Structure of the Region Shortly after Ohio became a state in 1803, Lake Erie was the The advent of the Canal led to great prosperity in Ohio. central means of goods shipment, but access from the eastern Small towns and cities were developed along the waterway, part of the country and the Ohio River in the south was lim- with places like Peninsula and Zoar benefiting from their ited. New York’s Erie Canal connected Lake Erie to the proximity to the Canal. -

NFBPA Sponsor Brochure 2018 F.Indd

EVOLVE LEAD INSPIRE Generations of Leaders EVOLVE LEAD INSPIRE Generations of Leaders WHY Become a CORPORATE SPONSOR? ENSURE FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES FORUM 2018 is a premier public sector conference scheduled in the most emerging city in the country. You owe it to yourself to be a part of FORUM 2018. Not convinced? Here are the reasons why you can’t afford to miss FORUM 2018 1. EMERGING TRENDS FORUM 2018 presentations made by top thought leaders representing leading cities, counties and companies. 2. EXPERTISE Learn about the latest public sector trends to give your company a solid edge over com- petitors. 3. COLLABORATION Brainstorm and interact with city managers, IT directors, public works and transportation experts from across the country. 4. ROI For the value of your sponsorship, you will be introduced to a wealth of information, insights and new ideas. 5. OPPORTUNITIES Propel your company to be positioned as a leader in the provision of public sector products. FORUM 2018, NFBPA’s annual conference offers a broad spectrum of educational, informa- tion sharing, best practices and networking opportunities. FORUM 2018, Evolve | Lead | Inspire provides the private sector a supreme opportunity to reach influential public administrators. Let’s get started today. Contact us on 202-408-9300 for more information. The National Forum for Black Public Administrators is the principal and most progressive organiza- tion dedicated to the advancement of ethnically diverse leadership in public service. NFBPA offers cities, counties and other levels of government resources and support to successfully deliver ser- vices to their employees and communities. NFBPA administrators are on the frontline working to solve pressing community and human service needs. -

City of Cleveland Location in the NOACA Region

CITY OF C LEVEL AND T HE C ITY OF C LEVELAND R OADWAY P AVEMENT M AINTENANCE R EPORT T ABLE OF C ONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Background ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. PART I: 2016 Pavement Condition ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 4. PART II: 2018 Current Backlog ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 34 5. PART III: Maintenance & Rehabilitation (M&R) Program .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

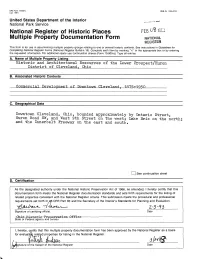

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

.NFS Form. 10-900-b ,, .... .... , ...... 0MB No 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) . ...- United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________ Historic and Architectural Resources of the lower Prospect/Huron _____District of Cleveland, Ohio________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Commercial Development of Downtown Cleveland, C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, bounded approximately by Ontario Street, Huron Road NW, and West 9th Street on the west; Lake Brie on the north; and the Innerbelt Jreeway on the east and south* I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in>36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. 2-3-93 _____ Signature of certifying official Date Ohio Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register.