Accessing an Archive of Korean/American Constructions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019

AML 2410—Issues in American Literature and Culture: American Empire and Territories, Spring 2019 Instructor: Ms. Rachel Hartnett Section: 5700 Meeting Times: MWF Period 7 Location: Matherly 0114 Email: [email protected] Office: Turlington 4321 Office Hours: Wednesday 9 AM - Noon, or by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION AND OBJECTIVES This course will focus on an important theme in the study of American literature and culture: empire. Many critics and citizens have argued that the United States of America is an inherently anti-imperial nation; however, this ignores the multitude of colonial enterprises and imperialistic tendencies of the U.S. While the founding fathers were resisting British colonial tyranny, American colonists were actively attempting to replace the indigenous population and settle tribal lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. The U.S. continued this removal of the native population, and began its wars of imperialism, in their drive for Manifest Destiny. The involvement of U.S. military forces in the coup of the Hawaiian monarchy, led by the American businessmen in Hawaii, marked the first external connection to imperialism for the United States. Despite the nation’s decision to back independence-minded colonies of Spain in the Spanish-American War, it subsequently took over colonial authority for the Philippines, ignoring the budding First Philippine Republic. The U.S.’s imperialism shifted after World War II and began to be shaped through the use of foreign military bases, particularly in places like Japan and Germany. This only intensified during the Cold War, as the U.S. and the Soviet Union arose as true global powers. -

Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 5-5-2012 Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction Debora Stefani Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Stefani, Debora, "Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique ruong'T s the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESISTING DIASPORA AND TRANSNATIONAL DEFINITIONS IN MONIQUE TRUONG’S THE BOOK OF SALT, PETER BACHO’S CEBU, AND OTHER FICTION by DEBORA STEFANI Under the Direction of Ian Almond and Pearl McHaney ABSTRACT Even if their presence is only temporary, diasporic individuals are bound to disrupt the existing order of the pre-structured communities they enter. Plenty of scholars have written on how identity is constructed; I investigate the power relations that form when components such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, class, and language intersect in diasporic and transnational movements. How does sexuality operate on ethnicity so as to cause an existential crisis? How does religion function both to reinforce and to hide one’s ethnic identity? Diasporic subjects participate in the resignification of their identity not only because they encounter (semi)-alien, socio-economic and cultural environments but also because components of their identity mentioned above realign along different trajectories, and this realignment undoubtedly affects the way they interact in the new environment. -

Cool Cats at the Milkweed Café

Meadow Notes – Carrie Crompton Cool Cats at the Milkweed Café In my last post, I mentioned sightings of Monarchs in the Way Station on July 9 and July 18. On July 20, I found a scattering of eggs – looking like tiny pearls to the naked eye – on the undersides of the leaves of one plant in the milkweed stand: Monarch Eggs, July 20 The eggs are larger white globules on the leaves; the small flat white dots on the leaf vein are bits of oozing milkweed sap. This was encouraging! The next day, I saw my first Monarch “cats” (caterpillars) of the season: Monarch Caterpillar, Second Instar, July 21 As you can see, this little cat has munched through the leaf, creating a hole for the sap to ooze out of, leaving the leaf vein depleted of sap, and therefore easier to eat. The cat is very, very tiny compared to the midvein of the milkweed leaf, but it’s already in its second instar: you can see tentacles (sensory organs) beginning to “sprout” as black spots just behind the head (lower end of the caterpillar in this photo). If all goes well, it will eat and grow and molt (break out of its skin) again and again and again, until it reaches its fifth instar. There were several more tiny cats on the undersides of other leaves on the same plant. On the morning of July 25, I saw a number of eggs, a few more second-instar babies, and this really big cat. The front and rear tentacles are recognizable as such. -

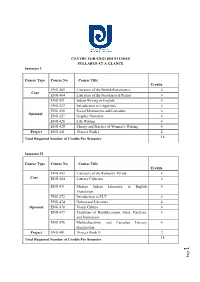

CENTRE for ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS at a GLANCE Semester I

CENTRE FOR ENGLISH STUDIES SYLLABUS AT A GLANCE Semester I Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 403 Literature of the British Renaissance 4 Core ENG 404 Literature of the Neoclassical Period 4 ENG 421 Indian Writing in English 4 ENG 422 Introduction to Linguistics 4 ENG 426 Social Movements and Literature 4 Optional ENG 427 Graphic Narrative 4 ENG 428 Life Writing 4 ENG 429 Theory and Practice of Women’s Writing 4 Project ENG 441 Project Work I 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester II Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 453 Literature of the Romantic Period 4 Core ENG 454 Literary Criticism 4 ENG 471 Modern Indian Literature in English 4 Translation ENG 472 Introduction to ELT 4 ENG 474 Nation and Literature 4 Optional ENG 476 Visual Culture 4 ENG 477 Traditions of Republicanism: Ideas, Practices, 4 and Institutions ENG 478 Multiculturalism and Canadian Literary 4 Imagination Project ENG 491 Project Work II 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 1 Page Semester III Course Type Course No. Course Title Credits ENG 503 Literature of the Victorian Period 4 Core ENG 504 Key Directions in Literary Theory 4 ENG 526 Comparative Literary Studies 4 ENG 527 Discourse Analysis 4 ENG 528 Literatures of the Margins 4 Optional ENG 529 Film Studies 4 ENG 530 Literary Historiography 4 ENG 531 Race in the American Literary Imagination 4 ENG 532 Asian Literatures 4 Project ENG 541 Project Work III 2 Total Required Number of Credits Per Semester 18 Semester IV Course Type Course No. -

The Ghost As Ghost: Compulsory Rationalism and Asian American Literature, Post-1965

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE GHOST AS GHOST: COMPULSORY RATIONALISM AND ASIAN AMERICAN LITERATURE, POST-1965 Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis, Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Directed By: Professor Sangeeta Ray, Department of English Since the early 1980s, scholarship across disciplines has employed the “ghostly” as critical lens for understanding the upheavals of modernity. The ghost stands metaphorically for the lasting trace of what has been erased, whether bodies or histories. The ghost always stands for something , rather than the ghost simply is —a conception in keeping with dominant Western rationalism. But such a reading practice threatens the very sort of violent erasure it means to redress, uncovering lost histories at the expense of non-Western and “minority” ways of knowing. What about the ghost as ghost? What about the array of non-rational knowledges out of which the ghostly frequently emerges? This project seeks to transform the application of the ghostly as scholarly lens, bringing to bear Foucault’s notion of “popular” knowledges and drawing from Asian American studies and critical mixed race studies frameworks. Its timeline begins with the 1965 Immigration Act and traces across the 1970s-1990s rise of multiculturalism and the 1980s-2000s rise of the Multiracial Movement. For field of analysis, the project turns to Asian American literature and its rich evocations of the ghostly and compulsory rationalism, in particular Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior and China Men , Amy Tan’s The Hundred Secret Senses , Nora Okja Keller’s Comfort Woman , Lan Cao’s Monkey Bridge , Heinz Insu Fenkl’s Memories of My Ghost Brother , Shawna Yang Ryan’s Water Ghosts , and Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being . -

(Books): Dark Tower (Comics/Graphic

STEPHEN KING BOOKS: 11/22/63: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook 1922: PB American Vampire (Comics 1-5): Apt Pupil: PB Bachman Books: HB, pb Bag of Bones: HB, pb Bare Bones: Conversations on Terror with Stephen King: HB Bazaar of Bad Dreams: HB Billy Summers: HB Black House: HB, pb Blaze: (Richard Bachman) HB, pb, CD Audiobook Blockade Billy: HB, CD Audiobook Body: PB Carrie: HB, pb Cell: HB, PB Charlie the Choo-Choo: HB Christine: HB, pb Colorado Kid: pb, CD Audiobook Creepshow: Cujo: HB, pb Cycle of the Werewolf: PB Danse Macabre: HB, PB, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Half: HB, PB, pb Dark Man (Blue or Red Cover): DARK TOWER (BOOKS): Dark Tower I: The Gunslinger: PB, pb Dark Tower II: The Drawing Of Three: PB, pb Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands: PB, pb Dark Tower IV: Wizard & Glass: PB, PB, pb Dark Tower V: The Wolves Of Calla: HB, pb Dark Tower VI: Song Of Susannah: HB, PB, pb, pb, CD Audiobook Dark Tower VII: The Dark Tower: HB, PB, CD Audiobook Dark Tower: The Wind Through The Keyhole: HB, PB DARK TOWER (COMICS/GRAPHIC NOVELS): Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1-7 of 7 Dark Tower: The Gunslinger Born ‘2nd Printing Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Long Road Home: Graphic Novel HB (x2) & Comics 1-5 of 5 Dark Tower: Treachery: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 1–6 of 6 Dark Tower: Treachery: ‘Midnight Opening Variant’ Comic 1 Dark Tower: The Fall of Gilead: Graphic Novel HB Dark Tower: Battle of Jericho Hill: Graphic Novel HB, Comics 2, 3, 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – The Journey Begins: Comics 2 - 5 of 5 Dark Tower: Gunslinger 1 – -

The Key to Stephen King's the Dark Tower

ANGLO-SAXON: THE KEY TO STEPHEN KING'S THE DARK TOWER ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English ____________ by Jennifer Dempsey Loman 2009 Summer 2009 ANGLO-SAXON: THE KEY TO STEPHEN KING'S THE DARK TOWER A Thesis by Jennifer Dempsey Loman Summer 2009 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE, INTERNATIONAL, AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES: _________________________________ Mark J. Morlock, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: _________________________________ _________________________________ Rob G. Davidson, Ph.D. Harriet Spiegel, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator _________________________________ Geoffrey Baker, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so grateful to Drs. Harriet Spiegel, Lois Bueler, Carol Burr, and Geoff Baker. Your compassion, patience, accessibility, and encouragement went far beyond mere mentorship. I feel very fortunate to have had the honor to work with you all. I am so grateful to Drs. Rob Davidson, John Traver, and Aiping Zhang for their wise counsel. Thank you to Sharon Demeyer as well for her indefatigable congeniality. I thank Connor Trebra and Jen White for their calming camaraderie. I am so grateful to my parents, Jim and Penny Evans, and my grandmother, Jean Quesnel, for teaching me the importance of coupling work with integrity. I am so grateful to my dear husband, Ed, for his unconditional support of my efforts. -

Time in Stephen King's "The Dark Tower"

Ka is a Wheel: Time in Stephen King's "The Dark Tower" Pavičić-Ivelja, Katarina Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2015 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:205178 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository Katarina Pavičić-Ivelja KA IS A WHEEL: TIME IN STEPHEN KING'S ''THE DARK TOWER'' Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the B.A. in English Language and Literature and Philosophy at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Dr Lovorka Gruić-Grmuša September 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Abstract .......................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER I. Background ..................................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................................4 II. Temporal Paradoxes in King's The Dark Tower ........................................................7 2.1 The Way Station Problem ........................................................................................10 2.2 Death of Jake Chambers and the Grandfather -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

A Description of Theme in Stephen King's Novel Carrie

A DESCRIPTION OF THEME IN STEPHEN KING’S NOVEL CARRIE A PAPER BY NAME : TAMARA REBECCA REG.NO : 142202013 DIPLOMA III ENGLISH STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OFCULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2017 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by Supervisor, Drs. Parlindungan Purba, M.Hum. NIP. 19630216 198903 1 003 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of North Sumatera In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Diploma-III in English Study Program Approved by Head of Diploma III English Study Program, Dra.SwesanaMardiaLubis.M.Hum. NIP. 19571002 198601 2 003 Approved by the Diploma-III English Study Program Faculty of Culture Studies, University of Sumatera Utara as a Paper for the Diploma-III Examination UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the board of examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirement for The Diploma-III Examination of the Diploma-III of English Study Program, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara. The Examination is held on : Faculty of Culture Studies, University of Sumatera Utara Dean, Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805198703 1 0001 Board of Examiners : Signed 1. Dra. SwesanaMardiaLubis, M.Hum( Head of ESP) ____________ 2. Drs. ParlindunganPurba, M.Hum( Supervisor ) ____________ 3. Drs. SiamirMarulafau, M.Hum ____________ UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I am Tamara Rebecca declare that I am thesole author of this paper. Except where the reference is made in the text of this paper, this paper contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a paper by which I have qualified for or awarded another degree. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of this paper. -

Translating Quechua Poetic Expression in the Andes: Literature, the Social Body, and Indigenous Movements by Maria Elizabeth

Translating Quechua Poetic Expression in the Andes: Literature, the Social Body, and Indigenous Movements by Maria Elizabeth Gonzalez A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip J. Deloria, Co-Chair Associate Professor Santiago Colas, Co-Chair Professor Bruce Mannheim Professor Javier Sanjines Associate Professor Gustavo Verdesio © Maria Elizabeth Gonzalez 2010 To my inspiration, my son, the shining and brilliant Miguel, to my best friend and mother, a shining star, Leonor, to the shining pillar of stalwart principle, my father Ignacio, to my brothers in every path, Gonzalo and Ricardo, always, to my criollo Conservative Colombian ruling class grandparents whose code of conduct and its core of kindness led my mother, and then me, down all the right paths, Carlos and Elvira the eternal lovers of more than sixty years, to Faustina, my grandmother who minced no words and to whom I gave the gift of lecto-scripted literacy when I was a girl, while she taught me how to know goodness when I see it without erring, sunqulla, and to all my polyglot kin, my allies and friends. ii Acknowledgments To María Eugenia Choque, Ramón Conde, and Carlos Mamani I owe my gratitude for sharing with me what it all meant to them, for inviting me to share in all their THOA activities during my fieldwork, their ground breaking meetings among Indigenous Peoples of the Andean region and beyond; to all the CONAMAQ Mallkus whose presence inspired, and to all the Quechua and Aymara women who shared with good humor sunqulla. -

A Concise Companion to American Studies

A Concise Companion to American Studies A Concise Companion to American Studies Edited by John Carlos Rowe A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition first published 2010 © 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd except for editorial material and organization © 2010 John Carlos Rowe Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ , United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ , UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ , UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of John Carlos Rowe to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.