Johnny Hodges Charlie Shavers Half & Half

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records to Consider

VOLUME XXIII BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 1992 Dec 12-13, 1992 Vocals have always been with BBJ PROGRAMS are subject to change due to un SINGING GROUPS us, even though swing pur avoidable circumstances or station convenience. Many ists tend to overlook the con requests are receivedfor tape copies o f the programs, tribution made by lyrics in popularizing the Big Bands but stringent copyright laws applying to the records that are the basis of it all. The Mills Brothers, the Pied used prevent us from supplying such copies. Pipers, the Sentimentalists, the Modernaires, the Ink Spots, the Stardusters and the Merry Macs all make ( RECORDS TO CONSIDER) recorded appearances on this salute to the vocal groups, along with a few instrumental and single vocal HERE’S THAT SWING THING Pat Longo hits of the forties. Orchestra -Vocals by Frank Sinatra, Jr. USA Records - 19 Cuts - CD or Cassette Dec 19-20, 1992 It’s a very special BIG BAND CHRISTMAS time with very special Billy May was one of the arrangers for this recording, music, captured as which immediately makes it a must-have. Pat Longo’s performed in the studio and in broadcasts during the Orchestra has a two decade history of solid perfor Christmas seasons of years past. Both Big Bands and mance, some of it a bit far out for some Big Band single vocalists recall the Sounds of Christmas in a traditionalists, but most simply solid swing. Sax man simpler time; perhaps a better time. Recollections of Longo was vice-president of a California bank until he Christmas experiences fill in the moments between the realized money wasn’t what he wanted to handle the music to weave a spell. -

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (Výběr Z Nahrávek)

JAMU 20160316-1 – DUKE ELLINGTON 2 (výběr z nahrávek) C D 2 – 1 9 4 0 – 1 9 6 9 12. Take the ‘A’ Train (Billy Strayhorn) 2:55 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Rex Stewart-co; Joe Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Barney Bigard-cl; Johnny Hodges-cl, ss, as; Otto Hardwick-as, bsx; Harry Carney-cl, as, bs; Ben Webster-ts; Billy Strayhorn-p; Fred Guy-g; Jimmy Blanton-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Hollywood, February 15, 1941. Victor 27380/055283-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 11. Pitter Panther Patter (Duke Ellington) 3:01 Duke Ellington-p; Jimmy Blanton-b. Chicago, October 1, 1940. Victor 27221/053504-2. CD Giants of Jazz 53048. 13. I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good) (Duke Ellington-Paul Francis Webster) 3:21 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra (same personnel); Ivie Anderson-voc. Hollywood, June 26, 1941. Victor 17531 /061319-1. CD Giants of Jazz 53046. 14. The Star Spangled Banner (Francis Scott Key) 1:16 15. Black [from Black, Brown and Beige] (Duke Ellington) 3:57 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra: Rex Stewart, Harold Baker, Wallace Jones-tp; Ray Nance-tp, vio; Tricky Sam Nanton, Lawrence Brown-tb; Juan Tizol-vtb; Johnny Hodges, Ben Webster, Harry Carney, Otto Hardwicke, Chauncey Haughton-reeds; Duke Ellington-p; Fred Guy-g; Junior Raglin-b; Sonny Greer-dr. Carnegie Hall, NY, January 23, 1943. LP Prestige P 34004/CD Prestige 2PCD-34004-2. Black, Brown and Beige [four selections] (Duke Ellington) 16. Work Song 4:35 17. -

Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and His Kentucky Club Orchestra

MUNI 20070315 DUKE ELLINGTON C D 1 1. East St.Louis Toodle-Oo (Duke Ellington-Bubber Miley) 2:54 Duke Ellington and his Kentucky Club Orchestra. NY, November 29, 1926. 2. Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington-Rudy Jackson-Bubber Miley) 3:14 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, October 26, 1927. 3. Harlem River Quiver [Brown Berries] (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields-Danni Healy) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, December 19, 1927. 2:48 4. Tiger Rag [Part 1] (Nick LaRocca) 2:52 5. Tiger Rag [Part 2] 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, January 8, 1929. 6. A Nite at the Cotton Club 8:21 Cotton Club Stomp (Duke Ellington-Johnny Hodges-Harry Carney) Misty Mornin’ (Duke Ellington-Arthur Whetsol) Goin’ to Town (D.Ellington-B.Miley) Interlude Freeze and Melt (Jimmy McHugh-Dorothy Fields) Duke Ellington and his Cotton Club Orchestra. NY, April 12, 1929. 7. Dreamy Blues [Mood Indigo ] (Albany Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) 2:54 The Jungle Band. NY, October 17, 1930. 8. Creole Rhapsody (Duke Ellington) 8:29 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. Camden, New Jersey, June 11, 1931. 9. It Don’t Mean a Thing [If It Ain’t Got That Swing] (D.Ellington-I.Mills) 3:12 Duke Ellington and his Famous Orchestra. NY, February 2, 1932. 10. Ellington Medley I 7:45 Mood Indigo (Barney Bigard-Duke Ellington-Irving Mills) Hot and Bothered (Duke Ellington) Creole Love Call (Duke Ellington) Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. NY, February 3, 1932. 11. Sophisticated Lady (Duke Ellington-Irving Mills-Mitchell Parish) 3:44 Duke Ellington and his Orchestra. -

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic

Impex Records and Audio International Announce the Resurrection of an American Classic “When Johnny Cash comes on the radio, no one changes the station. It’s a voice, a name with a soul that cuts across all boundaries and it’s a voice we all believe. Yours is a voice that speaks for the saints and the sinners – it’s like branch water for the soul. Long may you sing out. Loud.” – Tom Waits audio int‘l p. o. box 560 229 60407 frankfurt/m. germany www.audio-intl.com Catalog: IMP 6008 Format: 180-gram LP tel: 49-69-503570 mobile: 49-170-8565465 Available Spring 2011 fax: 49-69-504733 To order/preorder, please contact your favorite audiophile dealer. Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Shout-Cisco (three 200g 45rpm LPs). Joan Baez, In Concert. Vanguard-Cisco (180g LP). The 20th Anniversary reissue of Warnes’ stunning Now-iconic performances, recorded live at college renditions from the songbook of Leonard Cohen. concerts throughout 1961-62. The Cisco 45 rpm LPs define the state of the art in vinyl playback. Holly Cole, Temptation. Classic Records (LP). The distinctive Canadian songstress and her loyal Jennifer Warnes, The Hunter. combo in smoky, jazz-fired takes on the songs of Private-Cisco (200g LP). Tom Waits. Warnes’ post-Famous Blue Raincoat release that also showcases her own vivid songwriting talents in an Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Déjá Vu. exquisite performance and recording. Atlantic-Classic (200g LP). A classic: Great songs, great performances, Doc Watson, Home Again. Vanguard-Cisco great sound. The best country guitar-picker of his day plays folk ballads, bluegrass, and gospel classics. -

Black, Brown and Beige

Jazz Lines Publications Presents black, brown, and beige by duke ellington prepared for Publication by dylan canterbury, Rob DuBoff, and Jeffrey Sultanof complete full score jlp-7366 By Duke Ellington Copyright © 1946 (Renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP) International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2017 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke ellington series black, brown, and beige (1943) Biographies: Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington influenced millions of people both around the world and at home. In his fifty-year career he played over 20,000 performances in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East as well as Asia. Simply put, Ellington transcends boundaries and fills the world with a treasure trove of music that renews itself through every generation of fans and music-lovers. His legacy continues to live onward and will endure for generations to come. Wynton Marsalis said it best when he said, “His music sounds like America.” Because of the unmatched artistic heights to which he soared, no one deserves the phrase “beyond category” more than Ellington, for it aptly describes his life as well. When asked what inspired him to write, Ellington replied, “My men and my race are the inspiration of my work. I try to catch the character and mood and feeling of my people.” Duke Ellington is best remembered for the over 3,000 songs that he composed during his lifetime. -

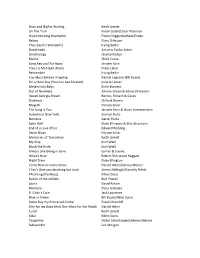

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett on the Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar

Days and Nights Waiting Keith Jarrett On The Trail Ferde Grofe/Oscar Peterson Good Morning Heartache Fisher/Higgenbotham/Drake Bebop Dizzy Gillespie They Say It's Wonderful Irving Berlin Desafinado Antonio Carlos Jobim Ornithology Charlie Parker Matrix Chick Corea Long Ago and Far Away Jerome Kern Yours is My Heart Alone Franz Lehar Remember Irving Berlin You Must Believe in Spring Michel Legrand (Bill Evans) On a Clear Day (You Can See Forever) Lane & Lerner Melancholy Baby Ernie Burnett Out of Nowhere Johnny Green & Edward Heyman Sweet Georgia Brown Bernie, Finkard & Casey Daahoud Clifford Brown Mayreh Horace Silver The Song is You Jerome Kern & Oscar Hammerstein Autumn in New York Vernon Duke Nemesis Aaron Parks Satin Doll Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn End of a Love Affair Edward Redding Senor Blues Horace Silver Memories of Tomorrow Keith Jarrett My Ship Kurt Weill Mack the Knife Kurt Weill Almost Like Being in Love Lerner & Loewe What's New Robert Sherwood Haggart Night Train Duke Ellington Come Rain or Come Shine Harold Arlen/Johnny Mercer I Can't Give you Anything but Love Jimmy McHugh/Dorothy Fields Pfrancing (No Blues) Miles Davis Dance of the Infidels Bud Powell Laura David Raksin Manteca Dizzy Gillespie If I Didn't Care Jack Lawrence Blue in Green Bill Evans/Miles Davis Some Day my Prince will Come Frank Churchill One for my Baby (And One More for the Road) Harold Arlen Coral Keith Jarrett Solar Miles Davis Tangerine Victor Schertzinger/Johnny Mercer Sidewinder Lee Morgan Dexterity Charlie Parker Cantaloupe Island Herbie -

Mi M®, 7273 the FUNCTION of ORAL TRADITION in MARY LOU's MASS by MARY LOU WILLIAMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Counci

37? mi M®, 7273 THE FUNCTION OF ORAL TRADITION IN MARY LOU'S MASS BY MARY LOU WILLIAMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By France Fledderus, B.C.S. Denton, Texas August, 1996 37? mi M®, 7273 THE FUNCTION OF ORAL TRADITION IN MARY LOU'S MASS BY MARY LOU WILLIAMS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By France Fledderus, B.C.S. Denton, Texas August, 1996 Fledderus, France. The Function of Oral Tradition in Mary Lou's Mass by Mary Lou Williams. Master of Music (Musicology), August, 1996,141 pp., 44 titles. The musical and spiritual life of Mary Lou Williams (1910 - 1981) came together in her later years in the writing of Mary Lou's Mass. Being both Roman Catholic and a jazz pianist and composer, it was inevitable that Williams would be the first jazz composer to write a setting of the mass. The degree of success resulting from the combination of jazz and the traditional forms of Western art music has always been controversial. Because of Williams's personal faith and aesthetics of music, however, she had little choice but to attempt the union of jazz and liturgical worship. After a biography of Williams, discussed in the context of her musical aesthetics, this thesis investigates the elements of conventional mass settings and oral tradition found in Mary Lou's Mass. -

"Extraordinarily Phones, the Clariry Is Jaw-Dropping

RECORD REVIEWS tAzz Through Grado SR-225 head- "extraordinarily phones, the clariry is jaw-dropping. Yes, surface noise is significant, but it POYYerful... varies th,roughout, sometimes within unGolor€d... a single track. Balancing pros and cons of sound quality versus historical .natural" value can make bootleg releases an ift proposition in general, but in this case -./ohn Atkinso4 Stereophih the lamer prioriry wins out. The historical importance of the 1940 recording of '8ody and Soul" by Coleman Hawkins that begins this COLEMAN HAWKINS & FRIENDS collection can't be overstated. Two The Savory Collection, Volume No.01: more swinging, beautifully arranged Body and Soul Hawkins numbers follow, then rwo Coleman Hawkins, Herschel Evans, tenor saxophone; from Ella with Chick Webb. Then a Ella Fitzgerald, vocal; Charlie Shavers, trumpet; come rouglrly 25 blissful minutes, six Emilio Caceres, violin; Carl Kress, Dick McDonough. tracks in all, from Fats Waller and His U guitar; Fats Waller, piano, vocal; Lionel Hampton, vibraphone, piano, vocal; Milt Hinton, bass; Cozy Rhythm (before nearly every number, Cole, drums; others Fats implores his public to "Latch National Jazz Museum in Harlem NJMH-0112 on!"). Next, in a Lionel Hampton-led (MP4).2016. William Savory, orig. prod., eng.; Ken Druker, Loren Schoenberg, reissue prods.; Doug jam session with Herschel Evans, Pomeroy, restoration, mastering. A-D. TT: 70:43 Charlie Shavers, Milt Hinton, Cozy jazzmuseuminharlem.org,/the-museum/ See hltp'.// Cole, and others, Hamp plays vibes collections,/the-savory-collection ? and piano and sings, blowing them all PERFoRMANcE ffi off the bandstand. Herschel's ballad soNrcs EXXdE fearure, "Stardust." compares interest- This music is culled from aluminum ingly with Hawk's "Body and Soul." and lacquer discs that, over the course The last rwo racks are more inti- of decades, rotted in the home of one mate curiosities, wonderful in their Bill Savory. -

STANLEY FRANK DANCE (K25-28) He Was Born on 15 September

STANLEY FRANK DANCE (K25-28) He was born on 15 September 1910 in Braintree, Essex. Records were apparently plentiful at Framlingham, so during his time there he was fortunate that the children of local record executives were also in attendance. This gave him the opportunity to hear almost anything that was at hand. By the time he left Framlingham, he and some friends were avid record collectors, going so far as to import titles from the United States that were unavailable in England. By the time of his death, he had been writing about jazz longer than anyone had. He had served as book editor of JazzTimes from 1980 until December 1998, and was still contributing book and record reviews to that publication. At the time of his death he was also still listed as a contributor to Jazz Journal International , where his column "Lightly And Politely" was a feature for many years. He also wrote for The New York Herald- Tribune, The Saturday Review Of Literature and Music Journal, among many other publications. He wrote a number of books : The Jazz Era (1961); The World of Duke Ellington (1970); The Night People with Dicky Wells (1971); The World of Swing (1974); The World of Earl Hines (1977); Duke Ellington in Person: An Intimate Memoir with Mercer Ellington (1978); The World of Count Basie (1980); and Those Swinging Years with Charlie Barnet (1984). When John Hammond began writing for The Gramophone in 1931 he turned everything upside down and Stanley began corresponding with Hammond and they met for the first time during Hammond's trip to England in 1935. -

1 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier and His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My

1 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Riverboat Shuffle 307A Muggsy Spanier And His V-Disk All Stars Shimmy Like My Sister Kate 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Redskin Rhumba (Cherokee) Summer 1944 307B Charlie Barnett and His Orch. Pompton Turnpike Sept. 11, 1944 1 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm You're Feets Too Big 308u, Hines & his Orch. Jelly Jelly 308u Fats Waller & his Rhythm All That Meat and No Potatoes 1 309u Raymond Scott Tijuana 309u Stan Kenton & his Orch. And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine 309u Raymond Scott In A Magic Garden 1 311A Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Summertime 311A Harry James And His Orch. Strictly Instrumental 311B Harry James And His Orch. Flight of the Bumble Bee 311B Bob Crosby & his Bob Cars Shortin Bread 1 312A Perry Como Benny Goodman & Orch. Goodbye Sue July-Aug. 1944 1 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Things Ain't What They Used To Be Nov. 9, 1943 315u Duke Ellington And His Orch. Ain't Misbehavin' Nov. 9,1943 1 316A kenbrovin kellette I'm forever blowing bubbles 316A martin blanc the trolley song 316B heyman green out of november 316B robin whiting louise 1 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet Which Switch Is Witch Aug. 14, 1944 324A Red Norvo All Star Sextet When Dream Comes True Aug. 14, 1944 324B Eddie haywood & His Orchestra Begin the Beguine 324B Red Norvo All Star Sextet The bass on the barroom floor 1 325A eddy howard & his orchestra stormy weather 325B fisher roberts goodwin invitation to the blues 325B raye carter dePaul cow cow boogie 325B freddie slack & his orchestra ella mae morse 1 326B Kay Starr Charlie Barnett and His Orch. -

Ed Dix Collection Finding Aid (PDF)

University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographical Sketch …………………………………………………………………… 2 Scope and Content …………………………………………………………………… 2 Series Notes …………………………………………………………………………… 3 Container List …………………………………………………………………… 5 Series I: Scrapbooks …………………………………………………………… 5 Series II: Awards & Honors …………………………………………………… 8 Series III: Interviews …………………………………………………………… 8 Series IV: Reviews & Articles …………………………………………… 8 Series V: Photographs …………………………………………………… 13 Series VI: Brookmeyer Memorial …………………………………………… 13 Series VII: Educational Materials …………………………………………… 14 Series VIII: Correspondence …………………………………………………… 14 Series IX: Miscellaneous …………………………………………………… 22 Series X: Brookmeyer Compositions/Arrangements …………………………… 23 Addendum I …………………………………………………………………………… 28 Series I: General Business …………………………………………………… 28 Series II: Publications …………………………………………………… 32 Series III: Correspondence …………………………………………………… 33 Series IV: Miscellaneous …………………………………………………… 48 Series V: Additional Photographs …………………………………………… 50 Series VI: Media …………………………………………………………… 50 Series VII: Oversize Material …………………………………………… 51 MS275 – Ed Dix Collection 1 University of Missouri-Kansas City Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections NOT TO BE USED FOR PUBLICATION BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tenor saxophonist, bandleader, and financial planner, Ed Dix was born in Kansas City in 1930. He began playing clarinet at age five, but switched to tenor sax at fourteen. While in high school, he toured the U.S. in bands styled after Glenn Miller’s. He was, himself, influenced by the playing of Lester Young, the tenor saxophonist in Count Basie’s band. For the first years of his adult life, Dix continued to tour in bands. It was Mary Ann (Dix’s wife, married 1950) who got him an audition for the Ralph Flanagan Band, with which he toured throughout the country – even playing at the Palladium. Dix also led a band of his own: The Eddie Dix Orchestra (“Music That Clicks with Dix”). -

Boston Book Fair, Nov. 2015

Sanctuary Books 790 Madison Avenue Suite 604 New York, NY 10065 212-861-1055 [email protected] www.sanctuaryrarebooks.com Boston Book Fair, Nov. 2015 1. 35 Artists Return to Artists Space: A Benefit Exhibition. Artists Space / Committee for the Visual Arts, 1981. Staple-bound illustrated wraps; 8vo; with b/w illustrations throughout. Covers faintly rubbed, else fine. Includes Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, David Salle, Robert Longo, and more. Fine. Paperback. (#D4201) $35.00 2. Le Chemin de fer Métropolitain de Paris. Paris: Les Ateliers A. B. C., 1931. Silver paper (printed and illustrated in red, blue, black, and white) over flexible boards; 4to; pp. [60], plus numerous photogravures in text, and full-color illustrated plates and maps. Boards bumped, creased; rear paste-down bubbling up in the gutter, otherwise text block is nice and clean. A visually striking volume on the Paris underground (subway, metro) system, presented in art deco style. Sold as is. Good+. Hardcover. (#D7988) $85.00 3. Collection of 23 Vintage Postcards of British Actors. An excellent collection of photographic postcards of late-19th and early-20th century English actors, from the Golden Age of British Theatre. All are in excellent condition, bright and clean (some are blank, others with contemporary handwriting), in sepia and b/w, one colored. Includes Dan Leno, Arthur Roberts, George Alexander, Martin Harvey, Herbert Campbell, Chirgwin (in black face, with his famous white diamond eye), and more. Very Good+. (#D4122) $250.00 4. Dean & Son's Coloured Six-Penny Books: Miss Mary Merryheart's Series: The Monkeys' Wedding Party. London: Dean & Son, [1856].